Introduction

The study of Science and Mathematics, for reasons unknown, has historically been a stronghold of men. Though numerous women have distinguished themselves in these fields and made their own mark, yet, the vast majority of scientists and mathematicians has always been, and still are – men. Early societies placed emphasis on the woman’s role in the household, and did not provide them with the opportunity to learn much of the world outside their home. Women were seen as being incapable of higher scientific reasoning.

All this was to change in the nineteenth century, when women finally established their presence in the workplace, as well as academics. The industrial revolution changed the way many industries functioned; while mechanization did away with the emphasis on brute strength and made the workplace conducive for women staff. This was also a period when British society was at a crossroads between the new world and the old. The industrial revolution was just around the corner, but it was also a time when Europe was still in the grip of the “romantic era”. Dissent against aristocracy, as well as social and political norms of the day was common; while scientists were ushering in an era of new-found knowledge, the artists were reacting against the scientific rationalization of everything around them.

There were two major schools of thought in prevalence at the time – Subjectivism and Objectivism. The Objectivists would study science, reason, and explained the world around them in scientific and rational terms. The Subjectivists were given to a more romantic idea of the world, and propagated the value of creativity and imagination, while deriding science as “dehumanizing”.

Nature and Genetics Play their Role

George Byron, popularly known as Lord Byron, was one of the most celebrated British poets of the time and a leading figure of the “Romantic Movement”. He famously argued against the advent of technology in front of British Parliament. He went on to marry a famous mathematician – Anna Isabella Milbanke. A daughter, Ada Lovelace was born on 10th December, 1815, to George Byron and Anna Milbanke. Her given birth name was Augusta Ada Byron and she was a powerful combination of her illustrious parents qualities.

Anna Milbanke was accomplished in her own way, well known as an excellent mathematician and poetess. Lord Byron would lovingly refer to her as the “Princess of Parallelograms”. She was an heiress to a large estate and was highly regarded for her high intelligence and moral views. Lord Byron, on the other hand, descended from a long line of men given to womanizing and mental instability. Their marriage was doomed from the beginning, owing to Lord Byron’s numerous sexual trysts, which included men as well as women from all sections of London society. It was widely speculated that he married Anna Milbanke only for her sizable inheritance. Seemingly tired of his notoriety in London social circles, Anna left Lord Byron soon after the birth of their daughter Ada, and walked out of the marriage on 16th January 1816.The couple signed the separation papers soon after, and Lord Byron left England the same year, ruling out any future reproachment between the couple. Anna continued to make allegations about Lord Byron’s immoral behaviour for the rest of her life, while “praising his genius” publicly, at the same time.

A Blooming Mind Needs Nurturing

The controversy surrounding the bitter divorce soon spiraled into public domain, and combined with Lord Byron’s decadent social image to give ample fodder to London’s gossip circles. Anna Milbanke was determined to shield little Ada from these lascivious stories, and tried to hide as much of Lord Byron’s life from their daughter as she could. She decided to encourage Ada’s scientific and mathematical skills, to counter any artistic tendencies she might have. Accordingly, the little girl was made to pay more attention to Mathematics and Science than Literature and Arts, lest she acquire her father’s “impulsive” ways.

Lord Byron had hoped for the child to be a boy, and as such he was disappointed upon finding that his firstborn was a girl. He last saw the girl when she was less than a month old, never to see her again. He never attempted to contact his daughter, but left instructions with his sister to keep him informed of her welfare. Lord Byron died in Greece, while fighting in the Greek War of Independence, when Ada was eight years old. Ada never saw any pictures or portraits of her infamous, yet illustrious father until she turned twenty. A life size portrait of Lord Byron was present in the living room of the Milbanke home but it was shrouded with a curtain and no one was allowed to view it.

The little girl was named after Lord Byron’s half sister, Augusta Leigh - with whom he was rumoured to have had an incestuous relationship. London society of the day was abuzz with whispered stories of the affair, though some believed Anna to be the true source behind them. It was rumoured that Byron and Augusta had a daughter – Elizabeth Medora. Though it was never confirmed to be true, Elizabeth was never close to Ada and the two would avoid each other whenever possible, even though Elizabeth and her daughter were supported financially and emotionally for a number of years by Anna, and then Ada.

Ada did not share a close relationship with her mother. Even though Annabelle was always concerned about her and made all efforts to give her a good childhood, she was often away from the child, leaving Ada in the care of her grandmother, Judith Milbanke. Annabelle continued to inquire about Ada in her correspondence with Judith, but would never show any outward affection or real concern towards the child. In some of the letters, she referred to Ada as “it” and made specific requests to preserve the letters in case she was required to show them as evidence of correspondence with her daughter.

However, Anna ensured that Ada received a meticulous education and engaged the services of some of the foremost British academicians, like Mary Somerville – one of the most prominent female physicists and mathematicians of the day, William Frend, William King and later in life, Augustus De Morgan. Ada, a highly intelligent child, reveled in her studies and was soon highly skilled in Algebra, Logic and Calculus – a highly unusual upbringing for a girl in Victorian England. By the age of eight, she demonstrated an interest in mechanical devices and built detailed model boats. Later, she also came up with sound designs for flying machines.

As a child, Ada was described as being frail and dainty, yet a charming girl with a lightness of step and attractive looks. She was full of high spirits and extremely unruly. She, however, suffered terribly from poor health. She fell prey to a bout of unexplained headaches when she was only eight, and her eyesight was severely impacted by it. Later, she was struck with measles at the age of fourteen, and was confined to complete bed rest for a year. It was only with the help of crutches that she managed to walk a year later, but full recovery took around three years. Ada’s rebellious attitude shocked her mother. She was prone to plumpness, and shared a love for food, like her father. Annabelle would often force Ada to lie motionless for extended periods of time, as she believed it would help her develop self-control.

Despite her rigorously scientific education, Ada was always interested in music and many of her friends conjectured that she would go on to become a famous musician someday. Ada’s education also included drawing and learning other languages, including French, at which she became an expert.

The Butterfly Plays the Social Circuits

Due to her illustrious parents, Ada grew up amongst the cream of London society and made many friends from the aristocracy and well-heeled gentry of Victorian England. She was a regular at the regal parties of the royal court; would attend theatre and concerts and was invited to aristocratic soirees. She was also well known amongst the scientific and literary communities, due to her own, as well as her mother’s well-known scientific background. She went on to count such illustrious people as Michael Faraday, Sir David Brewster, Andrew Crosse and Charles Dickens as her friends.

No stranger to controversy herself, Ada was sixteen when she had an affair with one of her tutors and tried eloping with him. The pair was found out, and Ada was sent back to her grandmother’s estate. This incident horrified Anna, and prompted her to start looking for suitors for Ada. She instructed some of her friends to keep an eye on Ada to prevent any more scandalous affairs. Ada would call them “the furies” and claimed that they made up stories about her.

Mary Somerville, who was her tutor, mentor and role model (being England’s leading lady scientist), took Ada under her wing. The two women would attend lectures as well as soirees together and shared a close friendship. Ada was a regular at the parties thrown by Mary at her home, where Mary introduced her to Baron William King, a friend of her son. Ada took a liking to William and in less than a year the duo got married, and Ada took the title of Baroness King. The couple moved to William’s estate in Surrey, where he continued to encourage her academic pursuits. The Queen of England soon elevated him to the position of an Earl, with the title of first Earl of Lovelace, and Ada became the Countess of Lovelace. Despite being ten years older than her, William was happy to let her be the dominant one of the two.

The Call of Destiny

Ada wanted to resume education immediately after her marriage in 1833, but she was soon pregnant with her first child. The couple was blessed with a baby boy in 1835, whom she named Byron, after her famous father. They were soon blessed with a daughter as well, in 1836, and named her Anna Isabella, after her mother. Her second son - Ralph, was born in 1839. It was not until after a span of two years that she was able to resume her studies, when she started learning calculus under Augustus De Morgan in 1840.

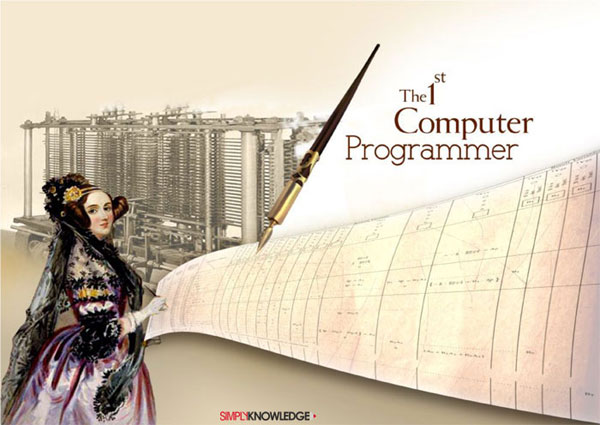

At the age of seventeen Ada attended a party where she met Charles Babbage, one of the foremost British mathematicians of that time. Charles Babbage is known as the father of the modern computer and was one of the first to begin studies into the field of computing, or simply speaking “problem solving through the use of machines”. He was well known for his highly unconventional approach to Mathematics and Economics as well as his strident, outspoken political activism. At this point in time he had been working on a device called the “Difference Engine”. The device was intended to calculate mathematical tables, by removing the human element and automating the process.

A few weeks after the meeting, Charles demonstrated the partially completed model of his difference engine to Ada and she was immediately captivated. He remarked, “She seems to understand it better than I do, and is far, far better at explaining it”. Ada was intrigued by this machine and curious to learn how it worked. She started studying Charles’ designs and would work on understanding the machine over the next few years. She soon became an expert on the subject and interacted closely with Charles on the development of the difference engine, leading him to remark, “that Enchantress who has thrown her magical spell around the most abstract of Sciences and has grasped it with a force which few masculine intellects could have exerted over it.”

The First Computer in the World

Charles Babbage was already planning the development of his next machine – the “Analytical Engine”. While the Difference Engine was designed to tackle simple problems like calculating tables, solving polynomial equations, addition and subtraction; the Analytical Engine was significantly more advanced. Charles Babbage had been so impressed by Ada’s skills and work on the Difference Engine that he invited her to collaborate with him on the project. Accordingly, Ada was briefed on the topic by Charles himself and involved in its development from the conceptual stage.

The Analytical Engine was demonstrated publicly only on one occasion, in 1840. Charles Babbage gave a lecture and demonstration of the machine’s capabilities to a group of mathematicians and engineers at Turin, in Italy. One of the attendees at that demonstration, Luigi Federico Menabrea took extensive notes on the machine and published a paper on the topic in 1842. The paper - written in French, with inputs from Charles himself, was titled "Sketch of the Analytical Engine". Menabrea focused his attention on the mathematical operations underlying the machines operation rather than the mechanical elements. He came to the conclusion that the Analytical Engine could solve any algebraic problem, if properly drafted and encoded (programmed) into the punched card. He wrote, "The cards are merely a translation of algebraic formulae, or to express it better, another form of analytical notation".

The Worlds First Program

Ada read Menabrea’s paper and started work on translating it from French to English. While doing so, she embellished the original paper with added footnotes and detailed explanatory sections, based on her own knowledge of the machine. Charles, aware of Ada’s acute understanding of the process, encouraged her annotations on the translation, resulting in the final paper being three times the length of the original. The translated paper, published in 1843, was more detailed and offered much more insight into the workings of the Analytical Engine.

The resulting paper, the highlight of Ada’s career, was to be the only such paper of its type on this subject for the next hundred years. Charles was highly impressed with Ada’s paper and presented it himself at many lectures. The paper was signed modestly as A.A.L., as Ada felt it was very unfeminine for a woman of her social class to be writing on a scientific paper like this. It was only thirty years later that the identity of A.A.L was known publicly.

The engine’s ability to receive information (data input) through the use of punched cards (programming) would go on to become the basic principle underlying modern computing. Ada wrote, "The distinctive characteristic of the Analytical Engine...is the introduction into it of the principle which Jacquard devised for regulating, by means of punched cards, the most complicated patterns in the fabrication of brocaded stuffs.... We say most aptly that the Analytical Engine weaves algebraic patterns just as the Jacquard−loom weaves flowers and leaves".

Ada was more interested in the programming aspects of the machine, or “sequences of instructions”, as she referred to them, in order to enable it to handle more complex tasks. The traditional approach to “programming” the Jacquard looms using the punched cards was to feed in the relevant card and once the design was printed, it was removed manually and replaced with another – an approach known as sequential programming. Ada, in her approach to the Analytical Engine was interested in manipulating this process so that once the data in the card was over, the machine would rewind back to the start, or loop only a particular sub-section, or even jump a section to the next – which would later come to be known as conditional programming. Using these principles, Ada went on to compute the first set of “programs” ever written, despite the Analytical Engine having never been completed. One of the first programs she wrote was designed to compute a sequence of numbers known as “Bernoulli’s numbers”, having familiarized herself with them during the course of her mathematical education with De Morgan.

Ada was quick to point out to the public that the machine was not “thinking” on its own as humans do, but acted mechanically on a set of coded instructions. She also drew a distinction between what the machine could theoretically compute and what was impractical. She proposed that the machine could, in theory, be used to generate music as well, something which is evident all around us nowadays. Modern computers can be used to automatically generate complex strings of music based on pre-programmed musical parameters. Few know however, that the first one to propose this was Ada Lovelace. In her own words, "Supposing, for instance, that the fundamental relations of pitched sounds in the science of harmony and of musical composition were susceptible of such expression and adaptations, the engine might compose elaborate and scientific pieces of music of any degree of complexity or extent."

The rest of Ada’s notes on Menabrea’s paper dealt with the process of programming the Analytical Engine, describing the punched card mechanism in minute detail and evolving a system of notation for writing the programs themselves. Charles Babbage was continuously impressed by the extent of Ada’s work, leading him to remark, "I am very reluctant to return your admirable & philosophic Note A. Pray do not alter it.... all this was impossible for you to know by intuition and the more I read your notes, the more surprised I am at them and regret not having earlier explored so rich a vein of the noblest metal".

Ada corresponded regularly with Charles regarding her progress on these and other topics and maintained a notebook of her current work. Many of these letters were printed subsequent to her death but the diaries were lost, thus consigning to history most of her pioneering research. She was open to Charles’ opinion and suggestions on the content of her notes, but rejected any changes to her prose by him. Shortly prior to the printing of the paper, Charles inserted a preface into the notes complaining about the British government’s lack of support for the Analytical Engine. Ada was furious upon finding out about Charles’ preface and instantly shot off an angry letter to him demanding that he withdraw his note. The matter was resolved amicably and soon the preface was published separately.

Personal Life

Ada continued to suffer from poor health into her adult years as well, falling prey to a bout of cholera, followed by Asthma and digestive ailments. She was continually medicated with strong painkillers such as laudanum and opium and started suffering from mood swings and hallucinations. Ada blamed her “intellectual abilities” to be the root cause of these maladies. De Morgan, who was more than impressed by Ada’s intelligence, also remained of the view that Ada’s frail body could not handle more mental effort and her health could be compromised if she continued to develop her mental skills. De Morgan and Ada were both rational people with a progressive bent of mind, but conformed to the widely held social beliefs of the time, which regarded women as physically incapable of scientific studies.

Soon afterwards her personality started to undergo changes, and she started boasting of her own intellectual talents. No doubt studying the newly established field of calculus gave an impetus to her understanding of science. Or perhaps having a stable family life of her own, away from her illustrious parents shadows, helped to boost her self-confidence. Nevertheless, she started describing herself evermore in self-aggrandizing, even delusional terms. She claimed that "a peculiarity in [her] nervous system, gave her perceptions of some things, which no one else has; or at least very few, if any. This faculty may be designated in me as a singular tact, or some might say an intuitiveperception of hidden things; that is of things hidden from eyes, ears & the ordinary senses."

Meanwhile, Annabelle confided in Ada about Lord Byron’s incestuous relationship with his half sister and the daughter borne out of that alliance. Ada took a small break from her studies, and travelled to France to meet her half sister Medora. Even though she claimed to have knowledge of this affair (through reading her father’s poetry), the news took a terrible toll on her health and she suffered a nervous breakdown soon after. Upon recovery she decided that she needed to reconcile her parent’s individual personalities into her own. She decided to call it “poetic science”, and wrote, "Religion to me is science, and science is religion. I am more than ever now the bride of science."

She restarted studies soon upon recovery, and after a few months took another break and shifted her attention to music and theatre. She soon started describing these arts as her "real and natural genius", and spoke of abandoning her pursuit of Science, in order to focus on Arts. It seemed Anna’s efforts had been in vain, and her father’s artistic instincts had triumphed over her mother’s scientific rigmorole. It could have been that she was tired and resentful of being goaded down the path of scientific research by her dominating mother as well as her husband. However, by 1843, she had resumed her study of Mathematics.

The Baggage of Brilliance

The extent of Babbage’s involvement in the notes eventually published by Ada remains unclear. There have been reports that claim he supplied her with the formulae, which were used to calculate the numbers – something he claimed himself in an interview after twenty-one years. It was also a matter of debate as to whose idea it was to use the Analytical Engine to compute Bernoulli’s numbers, though most people agree that it was Ada’s. Given her mathematical training with Augustus De Morgan she was certainly equipped to deal with the problem. Babbage had attempted several times to write the program for calculating Bernoulli’s numbers himself, but none of them were anywhere close to the complexity of Ada’s program. Ada wrote to Babbage, "I have worked incessantly, and most successfully, all day. You will admire the Table and Diagram extremely. They have been made out with extreme care, and all the indices most minutely & scrupulously attended to".

Ada herself was very impressed with her own work, and wrote to Babbage, "I do not believe, that my father was (or ever could have been) such a Poet as I shall be an Analyst (& Metaphysician). I cannot refrain from expressing my amazement at my own child (her Notes). The pithy and vigorous nature of the style seem to me to be most striking; and there is at times a half-satirical & humorous dryness, which I would suspect make me a most formidable reviewer. I am quite thunder-stuck at the power of the writing. It is especially unlike a woman's style surely, but neither can I compare it with any man'sexactly”.

Following her work on the Analytical Engine, Ada attempted to pursue other scientific work, but very little of it was original development or discovery; she would always prefer to work on other peoples research. She turned to a completely new direction by the mid 1840’s and took up gambling and betting on horse races. Her grandfather had been a lifelong gambler and womanizer and it seems Ada’s genetic makeup was heavily skewed in the direction on her father’s side. She claimed to have come up with a foolproof method for making vast amounts of money by gambling through mathematics, but had soon lost a small fortune and had to pawn her family jewellery twice in order to cover her losses. The losses kept mounting and she was soon forced to seek her husband’s help to tide over the mess.

Scientific research and Mathematics soon took a back seat as Ada spent more and more time on her new hobby. Numerous rumours also started doing the rounds regarding stories of her affairs with other men. Rumors also claimed that Babbage himself was the ringleader of the gambling syndicate fronted by Ada and that the two had come up with a mathematical way to beat the odds, and thus raise money to develop the Analytical Engine.

Throughout her life, Ada remained fascinated with the human brain, and pursued studies of nebulous fields like Phrenology and Mesmerism. These newly established fields, which were quickly dismissed as “quackery” by scientists of the day, attempted to influence and study human behaviour using unconventional methods. She confided in a friend about her desire to create a mathematical model for how the brain gives rise to thoughts and nerves to feelings ("a calculus of the nervous system") but nothing came out of it. She even attempted to learn from experiments in electricity and magnetism, so she could conduct her own research into these fields, but she did not get very far in these attempts. This irrational obsession was probably due to her mother’s insistence that Ada had inherited her father’s “insanity”.

Death & Legacy

Ada’s health continued to deteriorate, and she suffered a series of hemorrhages in 1851. The physicians addressing her could not find any plausible cause and resorted to blood letting – a common practice of the day where the doctors would make a small cut to the affected area, and let the “diseased blood” flow out. The treatment did not work, and Ada died on 27th November ,1852, aged thirty-six. The most likely cause of her death was presumed to be uterine cancer. She was buried next to her father, in Nottingham.

Ada Lovelace will always remain the foremost pioneer of computer programming. Despite her short life span, much of it was punctuated with illness and bad health. She carved a special niche for herself in the male dominated field of scientific research, changing many gender stereotypes among her peers along the way. She courted many controversies and lived a fulfilling life, refusing to rest on her parent’s laurels. The early computer programs, the highlight of her career, were only acknowledged to be her work in the 1950’s when computer pioneers decoded the A.A.L transcribed at the bottom of her notes. Her prediction of using computers to create music has already come true.

The US Department of Defense named their high level universal programming computer language, ADA in her honour.

Just imagine, the first person to write a language for a machine was the daughter of a poet and a mathematician.

Biography of Ada Byron King | 0 Comments >>

0 --Comments

Leave Comment.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked.