introduction

intoduction

Has anyone ever imagined a life without rubber products? Rubber goods such as elastic bands, raincoats, swimsuits, frogman suits, gloves, garden hoses, electrical wire insulations, packaging, life rafts, soles for shoes and boots have been used by many people. But who can forget the ubiquitous rubber that a student uses to erase pencil marks? Actually the list of rubber applications is endless. Thankfully, our modern life experiences with rubber goods are not boring. Our fast paced life in the 21st century is easier due to one of the important and useful materials that found a place in human civilization since the blooming industrial era. One 19th century inventor takes full credit for engraving rubber in our lives, Charles Goodyear.

Charles Goodyear, an American inventor discovered the ‘vulcanization’ process for treating natural rubber, that turned it into a practically functional substance. In the chase to make natural rubber suited to our present needs as a utilitarian material, Goodyear stands triumphantly at the forefront of the race. He was the first man to unlock the key to stabilize naturally obtained rubber and solidify its physical state. His discovery unleashed the rubber goods market and gave a tremendous boost to the industrial arts. It was a phenomenal effort that revolutionized the way rubber could be useful to us, in the form of rubber tires taking the lead. Charles Goodyear’s important initial discovery of the ‘vulcanization’ process has made rubber an indispensable material. Without his persevering efforts, our lives today would have been very slow, and different.

Though he bestowed a great gift to mankind by his invention, a lesser known fact is that his life story is a touching saga of a man who refused the pleasures of life, and endured countless trials and tribulations. To reach his heroic goals, he selflessly made dire sacrifices that were personal, and even met with devastating consequences. With strong willpower and determination, the great inventor and innovator introduced rubber as a material that added comfort to our lives with its diverse goods.

A Phase of Life in the Hardware Business

Charles Goodyear was born in the city of New Haven, Connecticut, on 29th December, 1800. He was the son of Amasa Goodyear and Cynthia Bateman. Of six children that the couple had, Charles was the eldest. His intelligent, generous and religious minded father, Amasa, was quite proud of being a descendant of Stephen Goodyear, one of the founders of the New England settlement of New Haven in 1638. Amasa Goodyear led the way in the manufacture of American hardware. The enterprising and visionary father mainly invented and sold agricultural tools like manure hayforks and scythes. Before him, it was generally the blacksmiths who would make farming implements out of wrought iron. His metal-ware business also included military buttons, spoons and clocks that engaged him in commercial ventures involving trade with West Indies. The family made huge wealth selling a tough and flexible steel fork, designed by Amasa. This patented agricultural tool bore the name - A. Goodyear & Sons.

A thorough gentleman and a noble Christian, Amasa was well respected in his community. He had a farmland in New Haven, where his son Charles would spend his boyhood days. When Charles was seven, his father Amasa bought a patent for manufacturing buttons and relocated to Naugatuck village, around 18 miles north from New Haven to make use of the precious water-power. From here, he was the first to begin a business of manufacturing pearl buttons in 1807. Amasa soon bought a nearby farm and young Charles would divide his time between the farm and the business to assist his father, often skipping Yale University’s public school in Naugatuck that he attended. Nevertheless, the young boy was somber and full of intellectual thoughts. Charles deeply respected his parents and was also reverently devoted to his mother Cynthia. An equally spiritual minded and dignified lady, Cynthia was regarded highly in the family. As an affectionate mother, she loyally taught her children and looked after them. Charles too inherited many characteristics such as his parents’ religious inclinations and piety.

By the age of 10, despite his limited schooling, Charles was seen as a studious boy with adult mannerism, unlike other children. He did not prefer the usual boyish games and devoted his time to reading religious poetry, books like the Bible and in his later years, The Book of Job. He frequently pondered over improvements that could be made in the objects of daily goods and articles that were constantly used by people. Quite early in his life as a schoolboy, he came across the raw latex gummy substance, also known as India rubber. Its physical nature, where it would melt and stick like elastic between his warm palms fascinated him. Once, after taking a thin scale of India rubber peeled from a bottle, it clicked to young Charles that if this gum elastic could be prevented from sticking together in a solid mass, then it could be useful as a thin fabric. This early boyhood impression of rubber would soon grow into a lifetime challenge of finding ways of rendering it practically valuable.

Charles displayed remarkable maturity and staunch religious passions at an early age of 11, when he would visit the Congregational Church in Naugatuck. Always eager to learn and pursue knowledge, he even wanted to become a priest in the ministry. However, being a close companion to his father in his business left the obedient Charles with no extra time to pursue it. In 1816, the 16 year old teenager went to Philadelphia after completing his school education, and was placed by his father as an apprentice in the store of Rogers and Brothers to learn the hardware business. He never completed higher studies, but at the workplace, Charles worked productively and diligently. Armed with this valuable experience, he then returned to Connecticut in 1821 at the age of 21 and joined his father Amasa’s hardware business as a partner. Amasa reposed immense confidence in his promising young boy Charles, and would consult him often in business matters. For the next five years, Charles worked and helped in building up the family business, from which they earned satisfactorily on his father’s inventions. Under the name Amasa Goodyear & Son, they manufactured a variety of metal-based items, ivory buttons, farming tools and machinery, designed by the ingenious Amasa.

Charles too was gifted with his father’s love for inventions and visioning article of use. It brought him immense happiness on observing that the tools and implements he sold, lightened the load of farmers, who toiled endlessly in their farms. This made an everlasting impact on his receptive mind, as he directed the course of his future life with an inventive disposition.

In August 1824, at the age of 24, Charles married Clarissa Beecher. She was the sister of Mr. William De Forest, his tutor when Charles was sixteen. Observing that the patented steel fork gave them good business, two years later, Charles moved to Philadelphia with his wife and established the first general retail hardware store in America, which sold his father’s steel fork and other farm tools. Here he also sold other agricultural equipments that were imported from England. The business flourished under Charles, bringing him a favourable reputation. This renowned business firm was then set up quickly in several American states. Over a span of few years, the couple was blessed with five children, four daughters, Ellen, Cynthia, Amelia and Amy, and one son Charles Jr. Surprisingly, not much information is available about their birth dates. By 1829, Charles was a wealthy man, who spent peaceful days with his family in Philadelphia, teaching his children the commandments from the Bible. Little did he know that fate had conspired against him, and his relaxing situation was about to change.

Beginning of Imprisonment Spells

Towards the end of the year 1829, Charles was attacked repeatedly with dyspepsia. This illness was the beginning of his health deterioration, often confining him to bed. By this time, his business too received a setback; because he gave goods on easy credits, he faced extensive losses from customers who refused to pay up. By 1830, Charles and his father were finally bankrupt due to their lacking business acumen. The dread of surrendering his rights to patent numerous unfinished agricultural inventions that were in the process of being finalized, prevented Charles from declaring himself and his Philadelphia business insolvent. Transitory respite was obtained as they received an extension for making payments. Yet, despite struggling for some time against the unfavorable winds, father and son lost their credibility and were forced to shut numerous stores.

Charles then briefly found himself in debtor’s prison in Philadelphia for non-payment of debts worth over tens and thousands of dollars. Thus began his series of repeated imprisonments. As he came in and out of prison, his years were filled with countless trials, harassments and bitter struggle, as he tried to provide for his dependant family through various small ingenious inventions. Even in prison, Charles was pushed himself to complete his unfinished agricultural inventions, in order to pay off his obligations to his creditors. The ever gentle Charles, submitted to the event as a misfortune, yet refused to shelter himself by any other means and remained cheerful and full of hope. His gentle wife Clarissa would dutifully visit him in prison, often leaving her infant behind with her daughter. She provided him much sympathy and unconditional support.

To this virtuous and extremely benevolent man, his life had a higher and meaningful purpose. So, Charles was quite unperturbed even within the prison walls, and lived with a clear conscience. Due to the difficulties in trying to recover his hardware business, after his release from prison he slowly winded up his firm. He felt after serious consideration that his failure detracted his creditors, and barred him from engaging in new ventures in the same field. So, he was now determined to make a living out of inventions within new projects, in completely different areas that fitted his capacity, and were amiable to his nature and liking. In his new role as an inventor, he fidgeted with equipments around, trying to find a better alternative for things like air pumps, faucets, spoons, etc. The days went by till sometime in 1831/32, when Charles began noticing a steady development in the rubber market as it grew. He then carefully began following every news report related to this new material and its products. This material would soon be his destiny and calling.

The Indian Rubber

In the early 1820s, the rubber fever was slowly gaining a hold in America, and by the early 1830’s Americans had even begun producing India rubber goods. This gum elastic substance or Latex, originally bears the name Caoutchouc (pronounced Koo-chook). Portuguese settlers of South America were the first to use this white, milky substance they called India rubber, and turn it into useful articles like garments, shoes, boots etc. This dense waterproof material proved to be a valuable defence against the rains. Due to the gum’s practical use of erasing lead pencil marks from paper, it was also simply known as rubber.

As the trees producing the gum elastic rubber grew in the Torrid Zone, bottles of it were prepared by the indigenous Indians of Brazil and imported to Europe and North America. The Indians, especially those living in the region of Para near the river Amazon, supplied the bottles and the substance became known as India rubber. Para also exported around three hundred thousand India rubber shoe pairs in the 1820s. When the Americans found that the gummy raw material in New England was good enough to make rubber shoes, the rubber enterprise began amidst tremendous speculation in early 1830s. Several large stores like the most famous Roxbury India Rubber Company of Boston began manufacturing and selling a variety of rubber goods across the country. It was assumed by many that rubber could be used for making thousands of useful objects. Many felt it was a profitable venture that could also make its investor wealthy. The print medium created its awareness, which raised inquisitiveness among the community people, including Charles Goodyear.

In 1834, when 34 year old Charles visited New York, he dropped by the Roxbury Company’s store to find out about their rubber products, chiefly life preservers. On taking a look at them, he instinctively felt that the tube which inflated the rubber life preserver could be improved upon, as it was weak in operation. Returning back from Philadelphia to New York after a couple of months, Charles displayed his improved version of the tube, thus gaining the agent’s attention. Impressed with Charles’ skill and design in crafting the tube and improving its effectiveness, the agent confided in him that the India rubber business was failing. He also informed that a huge compensation was due to be awarded if their product manufacturing and preservation problems could be solved.

The problem was that the India rubber had two main hitches. It softened in the summer to become sticky and could even melt at high temperatures; while in winter it hardened like rock and could crack. Roxbury Company goods worth several thousands of dollars were being returned now as the gum elastic had melted in the summer. Body heat was also enough to soften the products. These decaying goods threw an offensive odour and had to be buried under the earth. It also meant that any improvements done on India rubber had to be tested for a whole year to declare the goods flawless and usable. As a result, many India rubber product manufacturing factories in New England faced losses and perished. Even the rubber shoes made by the Indians in Para could not be depended upon in extreme weather of heat or cold. A negative feeling had arisen therefore amongst the people against rubber products.

Observing it all, the good-natured Charles immediately sympathized with the situation and felt it his mission to rescue the substance. It reminded him that as a child, when he went to play on a hot summer day, he found it difficult to run as the rubber sole of his shoes would melt and stick to the ground, while becoming brittle in winter. He began believing that he was the chosen one to liberate this unlucky, but important substance. This was the turning point in Charles Goodyear’s life, as this pious man would soon pursue experiments on India rubber.

Early attempts to Cure Rubber

Charles was inspired to perfect India rubber’s functional properties as he felt human civilization needed it. Determined, he then began the daunting task of conducting experiments on this uncured latex with the goal of improving its worth.

On his return from New York in 1834, Charles was jailed again for his failed Philadelphia venture. No wonder that his first experiments began within the prison walls and not in an equipped laboratory. He had no sponsorship money. But since the raw material for his experiments were inexpensive, i.e. a pound of the gum cost five cents, it helped him embark on many tests to dry and cure India rubber. His wife Clarissa respectfully brought him the substance and a rolling pin as his tool. He said later on these first experiments with his bare fingers, “Fortunately, the substance is one with which, in experimenting, fingers are better than any other mechanical power of the same force; and these formed the only mechanical power of which I had commanded during the first two years of my experiments, and that by which I mixed and worked many hundred pounds of gum, afterward spreading it upon a marble slab with a rolling pin. Thus, owing very much to the plastic nature of the substance, in extreme poverty, I was able to persevere in my course against all obstacles.”

Charles’ struggle as an inventor was met with abysmal complexities and personal difficulties as an insolvent debtor constantly courting arrests, having non-supporting friends who showed no faith in his experiments, suffering chronically in health and having a dependant family. To add to that he was not a scientist and was unfamiliar with Chemistry as well. But prior knowledge in this new field of rubber too was limited. European chemists had investigated the gum before. Though they had presented the analysed facts, none had given a practical solution to the huge problems it posed. The road ahead was unknown and vast. Yet, with incalculable trial and error, Charles was destined to transform India rubber into a miracle for human civilization.

a journey full of hardship

Putting his immense faith in the power of the supreme lord, Charles continued further tests on India rubber for the next five years. A kind gentleman from New Haven tremendously helped him in his hour of need. So on his release from prison, he was able to take up a cottage in New Haven and gather his family around him. Though still living in poverty, it gave these simple folks heartfelt joy when the entire family was together in enduring their affliction.

Without a proper laboratory, between 1835 and 1836, Charles worked in his house kitchen using basic equipments like pots and pans, just as he would experiment with equal zeal in the prison kitchens. Soon, supported by his friends with a modest monetary backing, he brought more raw materials, i.e. some pounds of India rubber, a phial of aqua fortis, turpentine and lampblack. For many hours together, Charles would work with India rubber in his hands. By dissolving India rubber in turpentine spirits, he changed the form of hard rubber into semi-liquid. Then along with a little lampblack for colour and magnesia to solidify it, he got a substance that was spread on flannel cloth. Thus, he first manufactured rubber shoes as they were easily sold. Besides hiring three or four women for help, who boarded with them, the entire family participated in making shoes for their daily bread, as per individual capacities. His oldest daughter, Ellen had recalled later proudly, that she constructed the first pair of rubber shoes. She had further said, “It was at this time, that I remember beginning to see and hear about India rubber. It began to appear in little patches upon the window panes and on the dinner plates. Father took possession of our kitchen for a workshop. He would sit hour after hour, working the gum with his hands.”

However, the arrival of next summer sealed the fate of the shoes, as all his efforts failed. The shoes had softened and became sticky. Even his neighbours complained about his rotting gum that released unpleasant smell. Failure of most of these early tests disappointed his friends who were cajoled by Charles for fund advances. Discouraged, they refused him even household supplies and further financial assistance.

Already leading a poverty-ridden life, Charles then tried to make ends meet by selling his household furniture to reimburse the assistance that he had received. Next, he shifted his family to a lodging house in a retired locality, keeping as security for unsettled fee, the linen that his wife had spun. To add to his distress, Charles was further burdened by his little son’s untimely demise, a great personal loss to him.

Firm Belief in His Divine Mission

Charles tripped and fell countless times as he kept on trying to find his answers. But during all these trying times, Charles, a deeply religious man, never lost his faith and belief, but reverently accepted whatever disappointments came in his path. He firmly believed that he was assigned to complete some great work in his lifetime, the benefits of which would be reaped by the whole world. Years later, he expressed his belief in the source of his inspirations during this period as, "reflection, that which is hidden and unknown, and cannot be discovered by scientific research, will most likely be discovered by accident if at all, and by the man who applies himself most perseveringly to the subject, and is most observing of everything relating thereto. This is corroborated and illustrated by the circumstances attending this discovery."

After managing to provide shelter for his family near New Haven where his family continued living under the charity of his friends, Charles relocated alone to New York, and found a single tenant's room, that he also used as his laboratory. Here, with full devotion and commitments, he began his laborious experiments in India rubber. A friendly druggist supplied him the necessary chemicals. His brother-in-law Mr. William De Forest visited him one day after a long time and was shocked to see the disheveled appearance of Charles, who looked worn out and ageing. The latter’s poverty was clearly visible, while his stained hands revealed his India rubber experiments. Charles told William, “here is something that will pay all my debts and make us comfortable.” The unhappy brother-in-law, taking note of the state of affairs advised him to look after his family and children as the rubber business was dead. Beaming with confidence, Charles answered him, “and I am the man to bring it back again.”

Charles then laboured doggedly in his experiments by boiling the gum with magnesia in a solution of quicklime. This seemed to bring results as the stickiness was destroyed. He soon managed to make thin sheets of rubber. In order to test this resulting compound material for its weather resistance capacity, he wore daily clothing made out of its thin sheets. Charles soon received wide acclamation, and even acquired a patent for this development method in 1935, by which he made beautiful ornamental goods, children's toy, globes, etc. He was even awarded medals at the fairs of American and Mechanic’s Institute. This creative man was happy with his invention till he noticed that weak acids turned the material’s beautiful dry surface into a soft and sticky substance once again. However, he did not lose hope and tolerantly carried on with full belief in himself.

A Glimpse of Success In The Horizon

Charles’ eldest daughter Ellen then gave him company in New York and they shifted to the attic bedrooms in a hotel. He soon gained permission to use a mill at Greenwich Village three miles away, where he secretly continued his tests, now coating rubber with an acid and metal. When his lime and bronze mixtures were prepared in the attic room for making rubber drapery, Charles would carry them on his shoulder in his gallon jug, walking the distance to the mill. During the course of making the drapery, he applied nitric acid to the India rubber material for eating out the bronze metal, but the rubber drapery discoloured and he cast it away. Days later, on examining it closely, he found that the surface felt different. The outer layer of India rubber was cured to a smooth, dry and manageable material as the adhesiveness was successfully eliminated.

Finally, on his substantial success with this next discovery in 1836, 36 year old Charles Goodyear made an India rubber cloth that was far superior to all his previous inventions or anyone else’s. Charts, maps, embossing, engravings, as well as beautiful prints could be transferred easily on this cured India rubber sheet. So he generously decorated his drab test samples by gilding and painting them. Happily, he then disclosed to his daughter that his great discovery was made. Charles’ accomplishment was even acknowledged by recommendation letters from President Andrew Jackson for this acid-cure treatment, and via a patent that he received in 1837. This discovery brought success and significant money to Charles, but accidentally, he also had a close brush with death. Always surrounded by the suffocating corrosive gases emanating from the harsh chemicals, he became ill for a few weeks. Though he lived through the incident, it proved detrimental to his health in the long run.

Bad Luck says Hi!

Charles Goodyear now won back the confidence of his people. With advance financial backing of several thousand dollars from a New York business partner, he leased warehouse buildings and set up manufacturing facilities at Bank Street in Manhattan and Staten Island for production of a variety of rubber articles with the help of steam power. Fabrication of beautiful goods soon began at these factories. After a long time of suffering, success seemed to embrace him in the distant horizon with prospects of a thriving future. Charles then shifted his entire family to his own home on Staten Island to live comfortably in their company. However, his bad luck played havoc again. In the economic panic of 1837, the fortune of his benefactor and his budding business was instantly obliterated. It was a big blow to Charles as his source of providing for his family was lost once again. This time his failure was attributed to absence of merit in his goods. His friends now turned their backs on any proposal of Charles and refused to invest with him. Penniless once more due to the disaster, he lived on the premises of the vacant Staten Island factory, feeding his family, fish caught in the port.

Consecutive failures meant that the inventor returned to the debtor's prison occasionally. Yet, his tender behaviour with his family rewarded him with deep love and affection from them. They too made sacrifices, self-denying their needs, and were willing to go through the ordeals of life along with him. Ever patient Clarissa lovingly took care of their children. She had economical habits, just like her husband and stood by Charles through thick and thin. As a devoted wife, she never criticized or rebuked him, but encouraged him gently in all his efforts by participating in his misery. Indeed, she was a blessing to Charles throughout his trails and tribulation.

Intermittently some acquaintance gave them money for food and small loans that Charles used for improvements in manufacturing rubber goods. In exchange for his daily bread, he gave up his furniture, umbrella, and the few remaining valuable possessions. Soon his family was left with their only prized article of a teacup set valued at fifty cents, which was used for breakfast as well as mixing India rubber compounds. He even made rubber plates when his cutlery was finally gone.

With access to machinery in the Staten Island factory, Charles made piano and table covers, ladies aprons, etc., out of India rubber, that provided them daily food when sold. His brother Robert, who too was living with them tried his best to contribute towards the living expenses. Despite striving diligently during six months on Staten Island, not a single investor could be persuaded to look at Charles’ improved process. His misery did not end here, as he was yet to see his darkest days.

Very soon Charles met Mr. J. Haskins, a stockholder of the Roxbury Rubber Company, who became his good friend and was extremely supportive of him. Despite facing losses himself, Haskins lent him money to continue when no one else would. He did whatever was in his power and capacity to help Charles who was deeply overwhelmed with gratitude. Along with Haskins, another kind gentleman, Mr. E. M. Chaffee, the founder of Roxbury Company, admired with interest Charles’ product samples and also displayed positive confidence in his new improved manufacturing process. After receiving the backing and financial assistance from his messiahs Chaffee and Haskins, Charles soon moved to Roxbury, Massachusetts, by late 1837, and began using their idle machinery. Soon, he invented a better method of constructing rubber shoes and obtained a patent for the same.

As was Charles’ usual practice, he sold the patent immediately to the Providence Company in Rhode Island, which although fulfilled his immediate pecuniary needs, yet, denied him continuous and long-term profits. The company then began manufacturing rubber shoes. Increasing demand for Charles’ diverse rubber products like carriage cloth, table cloth and piano covers, prompted him to sell his manufacturing licenses to several more companies. Soon enough, he gained profits of around four or five thousand dollars. His family now joined him in Roxbury in their pleasant Norfolk House. Though they eagerly welcomed the change in their lives, Charles used very little of his profits on family enjoyment and comfort. Besides producing rubber goods, majority of the profits from the sale of his invention were for the one predominant obsession in his life, to uncover how to stabilize India rubber.

Charles then got to know Mr. Nathaniel Hayward from Woburn, Massachusetts, in the summer of 1838, who was the founder of a former rubber company that had failed. Hayward had invented a rubber curing process, which involved drying and hardening India rubber by using a small amount of sulphur over it and exposing it in the sun. On finding that the outcome of the sun-drying process was the same as his acid-cure process, Charles was astonished, and he immediately bought Hayward’s patent for a nominal fee. Under Charles’ employment, Hayward continued experimenting along with him in Woburn, trying to improve upon the process, as they attempted to manufacture some useful goods like life preservers.

Charles also began new inventions with this new sulphur drying technique in the vacant Roxbury factory that had better machinery, and confidently made beautiful and imaginative rubber goods such as newspapers printed on rubber sheets. Meanwhile, the United States government gave him a contract for 150 India rubber mail bags. This got him wide publicity, just as he had intended. Charles had the hunch that now his highest expectations would soon be fulfilled. As he imagined the scenario of a sizeable income, he once again gathered his family, his aged parents and two younger brothers around him. The colourful mail bags were made in summer and attracted great admiration from the public, when displayed in the factory. Charles then went out of town for a few weeks and returned at the time of delivery of the order, to get unexpected results. He saw that the surface of the gum was “cured” and dry like a cloth, but underneath it was sticky and rotting away. The handles were falling apart! The compounds that Charles had added to impart different colours to the bags, proved disadvantageous. He understood that Hayward’s process helped in manufacturing the best quality rubber products, but it was restricted to only the outside layer. Yet, despite this fiasco, his guts never left him.

The Unyielding Crusader

Once again, Charles’ experiments had collapsed and the auction of his possessions followed. His factory work was closed down. His misfortunes were back and his perseverance was being tested time and again. His community people could now no longer endure the mention of India rubber. His moral backing and social support too had vanished as he received criticism and disapproval. He later said of this experience, "It was generally agreed, that the man who could proceed further with a course of this sort was fairly deserving of all the distress brought upon himself, besides being justly debarred the sympathy of others."

Regardless of the countless advice from his friends to pursue the familiar hardware business in agricultural tools, Charles listened to his inner guiding voice and ruthlessly continued amongst constant discomfort in treating rubber with sulphur. For a living, he simply took resort to manufacturing few saleable rubber articles by old methods. Always under the twin pressures of responsibility and poverty, he did not feel miserable and on the contrary, his optimistic mind was constantly occupied with this rubber curing problem.

Charles, now at an all time low in life, soon moved his family to Woburn. His difficulties were never-ending, yet without wasting any time, he continued his trials at his home workshop with whatever little he had. Along with two male helpers, he began manufacturing rubber shoes for sale. He had a happy family with whom he was lovingly attached, and could share tender moments of laughter effortlessly. Their presence gave him the strength to continue in his endeavours. His pious mother always reminded them to be grateful for what they had and believe in the future.

History’s Most Distinguished 'Accident'

The second crucial turning point finally approached in early 1839, when 39 year old Charles accidentally discovered the ‘Vulcanisation’ process. Charles’ experiments were now focused on finding the effect of India rubber mixed with sulphur. On the day of the important discovery, the events unfolded around a hot stove on a winter evening. Charles was sitting with his brother and a few acquaintances in his kitchen, chatting. He was holding a mixed piece of India rubber and sulphur in his hand when he made a momentary gesture, due to which the rubber accidently slipped and fell on the hot stove. He was astonished, as this piece did not melt or dissolve on the hot iron surface but appeared charred. The next morning, he was even more startled to find that though the piece was hanging outside overnight in the severe cold, it did not harden or become brittle. Rather it remained dry, flexible and waterproof, bearing a likeness to leather. On conducting a few further tests, Charles found that the periphery portions did not show any charring, but seemed flawlessly cured. This was a big breakthrough as he realized that the combined power of sulphur and high heat on rubber resulted in an intriguing substance which was soft and tough, yet pliable. It was also resistant to strong acids and weather across any temperature. It had exactly the properties which Charles was looking for. This perfected process was later termed as ‘vulcanization’, in which natural rubber is heated with sulphur to create ‘vulcanized rubber’, i.e. completely cured rubber.

Sulphur was indeed that blessed ingredient that astoundingly changed the properties of rubber when heated. Without it, rubber would be destroyed in heat, cold or acid. Excited that he had finally succeeded in finding a process, that thoroughly cured rubber to make it manageable and usable, Charles rejoiced triumphantly, trying to convince his friends of the value of his discovery. Sadly, they felt it was a figment of Charles’ imagination and did not pay him much heed. Another reason for them to ignore him was that the nearly charred and leathery rubber obtained was not in a serviceable state. This did not however dent Charles’ passion with rubber. On the contrary he kept on experimenting with his new found inspiration.

Several months later, Professor Silliman of Yale University, who had closely followed Charles’ developments, examined specimens and even gave a certificate supporting his methods and theories. However, the recognition and significance of his discovery outside his close family members was made after two years of stressful circumstances, when they were finally convinced of its magnitude. Charles Goodyear’s discovery was considered one of the most celebrated accidents in scientific history, something that he always denied by saying that it had meaning only for the keen observer who persevered in his experiments.

Rubber Obsession

Charles now applied his observations and newly gained knowledge in his tests. In order to perfect the procedure and arrive at the exact formula, he eagerly continued his tests on the exact measure of heat, the best form of applying it and precise amount of sulphur required for curing the India rubber. While his faithful wife baked bread loaves in the oven, Charles patiently waited. She too endured everything uncomplainingly. After they were removed, into the oven went a batch of India rubber. He studied the effects of baking them at intervals of one hour, two hours’, three hours’ and six hours’. Tolerantly, he would watch them all day, in the evening and throughout the night, expecting to find the cured rubber retain its original shape when deformed. He chopped rubber with axes and knives. He boiled them in saucepans and teakettles, roasted them in hot sand, and then cooked those using different approaches, in slow fire and quick fire over varying lengths of time. In each batch, he even altered the proportions of his mixing compounds and checked for decomposition of goods in heat and cold conditions, for over a year or more.

At last Charles successfully cured a thin rubber fabric in his bedroom where he had lit a huge open fire, and followed his routine of checking it by wearing it in the form of an apron, vest and cap. He even became the object of ridicule as he was seen wearing rubber clothes. His experiments continued in a few factories in the locality of Woburn. He went wherever he could found heat, and also used the fire of the kindhearted blacksmiths who, although considering him a madcap, consented to his repeated requests to use their fire. In the early months of 1839, Charles briefly shifted with his family to Lynn, in order to test the effects of steam in Mr. J. Haskins’ factory.

Days of Destitution and Endurance

As the summer of 1839 dragged on, Charles’ resources too began dwindling. So, he started making thick and large rubber specimens in his kind neighbour’s fields, depending on brushwood for fuel. He even built a brick oven for curing the specimens. These rubber products were nicely made, but the goods fermented thrice in that summer, remaining incurable. Not knowing the reason for this malfunction, Charles was now utterly dejected and inconsolable. Failures in his fight against decomposing rubber also contradicted his assurances of success to his friends, who now became intolerant to his stubbornness in chasing rubber experiments. The public around him inevitably lost their confidence in him and gave uncharitable views.

With broken health, Charles mustered all his courage and focused on completing his experiments. He was often besieged with fright at the slightest thought, that he might die and his invention’s secrets would vanish with him. So he would spend the nights staying awake. Charles’ destitute family members were sick too, yet went to the forest to collect wood for fuel, uprooting half grown potatoes for food. Nearby farmers gave the children milk. They were living each day as it came, at times lucky to receive a barrel of flour on charity. Charles even resorted to the extreme act of begging for his experiments, considering it noble to the purpose. A regular alternative was pawning his few remaining possessions like his watch, furniture and linen. Soon enough, selling his children’s schoolbooks brought him $5, which allowed him to carry on his tests to some extent.

Indeed, Charles had an eternal capacity to endure life’s evils, and was ready to give up everything for his goal. His life’s primary motivation was gifting his community his whole invention by showcasing the versatility of rubber. He never thought of the prospects of a fortune linked with it.

Principles vs. Opportunities

Very soon, in his time of need, Charles received an extremely beneficial and lucrative French offer from a firm in Paris, who intended to manufacture rubber goods by his earlier acid-process. In declining this opportunity, the man of principles, Charles Goodyear followed his conscience. He gave his reason that he would soon bring out a much superior process than the earlier one, and would inform the firm on its completion. This sacrifice proved costly for him as the visionary inventor soon entered the period of his worst humiliation. In the severe winter snowstorm of 1839-40, his family neither had food to eat nor any fuel to keep warm. Just like him, his young children were fighting a survival battle in his cottage that was half submerged in the snow. In this hour of hardship, there was no one to help him, not even his neighbours. Charles then remembered a kind gentleman from Woburn, O.B. Coolidge. Determined to seek his help, the weary man walked the miles through the snowstorm and narrated his tale to him, along with his new discovery and convinced him of the prospects associated with it. His generous benefactor then gave him enough assistance to last through the winter and also continue his experiments in a limited manner.

All the time, Charles studied single-mindedly to make accurate improvements in his vulcanization process and find a material that was flexible, elastic, firm and tough. But within his bare means, it was a futile exercise to try and prepare large sized rubber specimens bearing those properties. So he walked to Boston in the hope of receiving further assistance of $50 from an acquaintance. However, the aid failed to come through and Charles was jailed for non-payment of a $5 hotel bill. On his return home, he found that one of his children had died. Grief-stricken at his loss and in penury, Charles borrowed a wagon to take the body to the cemetery. After a simple memorial service, he reverently thanked his kind benefactor, and regretfully told his children that despite their personal grief, they must earn for a living. In his lifelong journey to solve one of the critical mysteries of the industrial age, the implacable Charles Goodyear repeatedly risked his own life as well as that of his family.

End of Bitter Suffering

Charles soon received a timely monetary relief from a kind friend, and also $50 from his rich brother-in-law Mr. William De Forest. This helped him reach New York where he showed his vulcanized rubber specimens to William Rider, a businessman and his brother Emory. Emory Rider too advised by giving him a practical opinion on hindrances in readying the machinery and preparing the vulcanized rubber goods. With the financial investment from the Rider brothers who admired his specimens, Charles began manufacturing vulcanized rubber articles. The Rider brothers, however, soon faced severe losses and their business operations had to be shut down. Meanwhile, a steady financial backing came in from his brother-in-law and Charles began a small factory in Springfield, Massachusetts in 1841, where he moved with his family. Here, with the help of his brothers Nelson and Henry, Charles conducted experiments and prepared vulcanized products such as rubber sheets, suspenders, elastics, elegant ribbons, etc. Success was finally knocking at his door.

In Springfield, Charles had his final debtor’s prison experience in America, after which he shielded himself from the wicked trials and tribunals by resorting to the ‘Bankrupt Law’ that covered him from his cruel prosecutors. He then toiled rigorously to devise diverse new uses for the versatile rubber substance. After several time consuming days, months and years of research and money draining tests, the talented man produced variations in the material as well as in the articles of use. He even perfected their production process, thus enabling a profitable business venture for many people. Vulcanized rubber articles attracted the public eye and also brought good profits by their sale. Since then, Charles never again reached the phase of extreme destitution. But as his fortunes turned bright and prosperous, instead of seeking legal benefits for himself by the bankrupt law, he turned his attention towards repaying old debts to creditors in the years ahead, amounting to nearly $35000. He also returned the kindness of all who had helped him in his adversities, by helping them in their misfortunes. He even gave openheartedly to the poor and supported many families for years when he had the money.

Goodyear’s Versatile Rubber

In the years that followed, with time and patience, Charles was successful in demonstrating that this extremely adaptable rubber material had over 500 distinct applications in the arts and in useful fabrications. A new factory was then started by Charles’s brother Henry, at Naugatuck in 1843, and the mechanical process of mixing was introduced. A market full of rubber goods arrived in the scenario. Some articles were winners while others were not. India rubber cloth, the rubber fabric deemed as the next important discovery after the vulcanization process, was perfected after years of costly tests. Charles invented the rubber water-bed used in army hospitals. Rubber wear became popular as it could shield people and protect them from winter and rain. It also gained importance in the electrical industry, since it was a bad electrical conductor. He crafted all imaginable rubber products such as cutlery set with India rubber handles, jewellery, musical instruments, book covers and India rubber floor tiles. With a patriotic fervour he could imagine rubber goods such as flags, ship sails, cheques and even banknotes. He carried a rubber purse and wore a rubber hat. His business cards, nameplate and autobiography were made and bound in rubber. His portrait too was painted on rubber. Everywhere his creative mind tried to replace leather, so he made army tents, blankets, gun cover, ponchos, wagon covers, pontoons, lifeboats, etc.

Charles would persistently think of new applications for rubber. Even while in bed, despite bearing pain due to gout, he could right away capture his ideas as he kept writing materials within his reach. With a rubber walking stick, the frail man would visit factories and try to convince people to use rubber tools. At rubber factories, he would even stress the need to modify a process to introduce his new inventions. But many companies having his manufacturing licenses would refuse and defy, as they were aware of the huge cost factor involved in producing a new rubber product. His friends too would request him to earn steady royalties from the already established market trade like rubber hoses, rubber elastics and clothing, rather than trying out manufacture of new articles, but he would turn a deaf ear.

Goodyear Receives His Patent

Charles Goodyear was slow to apply for his vulcanization patent in America. Only after he was finally confident of the results and convinced that at last he had perfected the formula for stabilizing India rubber, did he apply for a patent for ‘Vulcanisation’. In the meanwhile, since Europe led the industrial era by dominating markets in manufacturing and research, even before filing his American patent, Charles sent specimens overseas to Europe in 1842 to attract British financers, without divulging its manufacturing details. In one well-known British rubber firm in England, Charles Macintosh & Company, the rubber samples were examined by the well-known Thomas Hancock. Hancock was a pioneer of rubber goods in Britain since it first appeared in Europe in the early 1820s. In Charles’ sample, he noticed some traces of the sulphur compound. This clue was enough for the intelligent man Hancock, and he too carried forward his rubber experiments in England with sulphur. Hancock rediscovered the stable vulcanized process in 1843 (four years after Charles), while his friend, a rubber goods manufacturer, James Brockedon named it ‘Vulcanisation’ after the Roman God of fire ‘Vulcan’. So, the word ‘Vulcanisation’ was not coined by Charles Goodyear.

Ten years had elapsed since Charles had begun his great work and endured the bitter struggle involved. After spending almost $50000 in development, Charles Goodyear finally received his most important American patent for vulcanized rubber on 15th June, 1844.

Opponents and Litigations

By the time Charles Goodyear applied for his English patent, it became known that Thomas Hancock had claimed his first right in inventing the ‘vulcanization’ process and had applied just 8 weeks earlier than Charles in November 1843. In the process, Hancock tried to steal Charles’ reputation and even blocked his attempts to receive an English patent. Later, Hancock offered Charles half a share of the English patent to withdraw his suit, which the latter refused unwisely. Hancock received his English patent in 1844, while in the following few years, Charles received patents in most European countries except England.

The rubber industry that was almost non-existent a decade back, had regained a new lease of life by 1845. It was flourishing due to the unrelenting efforts of this extraordinary genius, Charles Goodyear, who was now leading a much easier life in New Haven. Devoted to his undertaking, Charles envisioned that every human being should be able to derive the benefits of the various uses of rubber, which were meant for all times. His creative work kept him from diverting his mind towards numerous enemies and immoral souls who were prospering at his expense, while scheming to deprive him of his little royalties and modest recognition. Yet, Charles fought legally for around seven years (till 1852) to protect his valuable patents and rightful claim to inventing the ‘vulcanisation’ process. He faced the impediments in his path by saying, "Don't be seeing all the difficulties that may possibly occur. If it is to be done it must be done, and it will be done."

Charles had to struggle against 32 cases of violation of his patent rights against the crooks that declined to pay him royalties but wrestled to uphold their rights against him to produce rubber goods. Among the men who contested lengthy lawsuits against Charles was Horace H. Day from America, who also obtained several manufacturing patents. Horace infringed on Charles’ patents repeatedly, with malicious intentions of ripping him off his riches. Charles then hired a lawyer and Secretary of State Daniel Webster. In order to protect their rubber goods production interests against Day, Webster was paid $25000 by Charles’ manufacturers who owned his licenses. It was a huge fee ever paid to any American lawyer at that time, and though well-known, Webster got involved as he needed the money. The infringement cases reached the Supreme Court where Daniel Webster finally won the memorable trial in 1852 against Horace H. Day in Trenton, New Jersey. Webster also obtained a lasting order against future patent infringements that honoured Charles Goodyear as the original single inventor of vulcanized rubber, though it did not stop the pirates much.

Visit to Europe

When finally most of his lawsuits were settled, Charles set off for Europe with specimens of his vulcanized rubber goods. He never received an English patent, though later, he could prove his credentials with his knowledge and expertise. Charles managed to win back his recognition as the original inventor at the English court of justice, as Thomas Hancock also acknowledged that he first noticed Charles Goodyear’s samples of vulcanized rubber when they were sent to Europe.

Charles’ main purpose in England was to persuade the manufacturers abroad to join him in the prospective business of successfully making India rubber articles using his patented process. He then participated in his first International Exhibition at the Crystal Palace in London in 1851 that provided him wide exposure and recognition. On this occasion, he displayed his elegant India rubber specimens that he had improved upon in America. The exhibition pavilion made of rubber, including the articles made by him cost an enormous sum of thirty thousand dollars, where he displayed breathtaking India rubber goods such as beautiful inlaid home furniture, medals, ornaments, rubber gloves, musical instruments, paintings on hard rubber etc. His equally beautiful stall occupied the maximum exhibition space compared to other American stalls. Though he earned practically nothing, Charles received appreciation by being conferred with the highest award at the fair, the "Grand Council Medal".

Next year, despite being challenged by physical sickness, Charles went with his family to Liverpool and remained there for some months, with the hope of negotiating and receiving some benefits for damages due to loss of his true patent in England. He thought it was his opportunity to be suitably compensated by applying for plenty of patents for rubber applications, as the English law had now turned favourable. However, most of his valuable articles had already found their way to the market by the English manufacturers and so, Charles’ negotiation efforts were in vain, and so he shut all his efforts.

Sometime in 1853, Charles Goodyear wrote the book, "Gum Elastic with its Varieties with a Detailed Account of its Application and Uses, and of the Discovery of Vulcanization." Only 12 copies of this voluminous book were printed on gum elastic page and circulated privately.

Death of Goodyear’s beloved wife

Charles soon received a devastating shock in his life, as his beloved companion for thirty years, his wife Clarissa, died in March 1853, at the age of 49 after trying to cope with her slowly failing health. Charles would confide in her, and had complete faith in her to bring up his children with ethical, moral values, culture and religious principles in his periodical absence from home. Clarissa was a very matured and intelligent lady, who always held the closely knit family together. She controlled his family life and was the center of his family’s happy atmosphere. He depended on her emotionally and believed in her wise judgments too. She willingly shared all his sufferings, and that was Charles’ biggest relief.

While Charles’ frail and weak body would suffer with chronic pain due to gout in Liverpool, his affectionate wife Clarissa would understand his signs and body language, as he was too weak to talk. Sitting quietly besides him, she would soothe him by her mere presence, when he would panic even when a stranger came close to him in his room. On hearing her voice as she read the scriptures or uttered comforting words, he would be rejuvenated and brace up to advance his work. During his severest troubles, she alone had the blissful energies to comfort him always. Her death was a tremendous personal loss to Charles, for they shared a very close and harmonious relationship.

Destiny soon favoured 54 year old Charles as he again found a fulfilling domestic relationship with an equally supporting lady of good character in London, the 20-year old Miss Fanny Wardell. Their marriage in 1854 broadened his social circle with his new wife’s relatives, who deeply respected Charles for his hospitable manners, religious commitments and friendly temperament. Together, they also had three children. With his spirits rebound and health on a road to a faster recovery, he soon began preparation for another French exhibition. Feeling the need to facilitate prospective business in France too, he soon moved with his family to Paris in November 1854.

Goodyear in France

An American company was already manufacturing rubber shoes and boots in France with Charles’ license since the end of 1852. This generated a great deal of prospective business interests. On arriving in France in 1854, Charles Goodyear then placed the reigns of his supervision and management duties with Charles Morey, an enterprising American businessman. Morey knew French fluently, and would negotiate with the French manufacturers well. Within a few months, his extreme skill and astute business capabilities were for all to see. Charles’ French patent was the first European patent that he received for vulcanized rubber. Under Morey’s leadership, three companies received Charles’ license to start manufacturing vulcanized rubber goods. The first products, mainly rubber shoes, met with tremendous success and the business grew to a healthy magnitude sooner than expected.

As his French business grew rapidly, promising forecasts of huge profits led Charles to plan lavishly for his French exhibition, “Exposition Universelle,” to be held in Paris in 1855. The American committee members, on noticing that very few Americans participated in the exhibition, further insisted that Charles fill up the spaces with his rubber goods. Encouraged, Charles prepared with a nationalistic pledge to represent his motherland and celebrate the aesthetic art of rubber. It cost him fifty thousand dollars for two elegantly designed and centrally placed courts containing beautiful India rubber goods such as rich ornamental jewellery, finely carved caskets, portraits painted on rubber panels, furniture, etc. Since then, trade in the extremely beautiful India rubber jewelry expanded immensely as its popularity increased.

Charles’ exorbitant expenses for this magnificently winning exposition appeared as a sensible investment to him, but Morey’s mismanagement brought him great losses, and it turned out to be ill-fated to his fortunes. Meanwhile, there was an unexpected turn of events as grave complexities loomed in front of the French rubber companies that had begun operations. They lacked the expert manpower to mix rubber compounds and the relevant machinery to work. Simultaneously, Charles’ businesses in America were badly hit as he faced problems in imposing his American patent rights. It caused a ripple effect in the French rubber companies, resulting in a slump in business. Charles’ French patent too was held back for a trifle reason due to which he stopped receiving French royalties. Once again he was bankrupt and in debts.

On 5th December, 1855, Charles was thrown into his familiar ‘hotel’, the debtor’s prison in Paris for 16 days. Mrs. Fanny Goodyear now stood by the side of an extremely fatigued Charles, walking on his crutches. She took on the role of his French interpreter and also requested the help of Charles’ kind business associate to secure his release. In prison, Charles silently bore extreme pain due to gout. It was here that his son conveyed to him that he was conferred with the highest honours from the French Emperor, "Grand Medal of Honor” and the “Cross of the Legion of Honor" for his participation in the French exposition.

Selfless service towards fellow beings

Charles’ trials and unfortunate experiences in a foreign land did not deter his spirits. The sensitive man spent his prison days with his favourite book, The Book of Job. Upon his release, a sick and skinny Charles went to his agency to secure for his prison mates gifts of rubber garments to comfort them within the damp prison walls.

Charles returned to England soon after his release from the French prison to be arrested again in London in connection with the French problems. Though it bothered him, he refused help of his British well-wishers and was respectfully released upon bein proved that he was a victim of deceit. His worsening health due to chronic sicknesses left him hopelessly dejected, and the danger of a sudden death was a large threat. Slowly, he moved to Bath, in England, in April 1856 where he remained confined to his bed. Throughout these days, amidst mental pain, Charles perseveringly pursued his research and investigation in the application of India rubber. On the bed where he would lie, he was also seen working, surrounded with the rubber substance. His room was also his office. In England, despite his severe illness, he spent his efforts in completing life saving inventions that were coincidentally his first and last experimental labours.

Economically too, Charles was in a sorry state of affairs, so he now traded his wedding presents and wife’s gold and diamond jewellery for money, to continue his experiments on life preservers. He would tell of lives lost at sea, “most men continue to be drowned because their fathers were? Must treasures continue to go to the bottom of the deep because there are offices where they are insured?” With firm faith within himself, Charles conscientiously continued and finally invented many types of life saving equipments.

During these years in England, till he left for America in May 1858, Charles Goodyear’s businesses in America were in disarray from the violation of his patent rights by infringers. While the gout-ridden and frail in health inventor spent large amounts in his continuous experiments, he was unable to defend himself from patent pirates in America who gobbled away his profits. Charles had barely any means to keep his patents alive in litigations. After returning to New York, Charles applied for its extension purely on its merits. Though there were greedy opponents who wielded money power and political influence to deprive him of his recognition, he was fortunately granted his patent extension in 1858 for seven years by the Commissioner of Patents, who said on Charles, "No inventor, probably, has ever been so harassed, so trampled upon, so plundered by that sordid and licentious class of infringers known in the parlance of the world, with no exaggeration of phrase, as 'pirates.' The spoliation of their incessant guerrilla warfare upon his defenseless rights have, unquestionably, amounted to millions."

Final Years

In his final two years of life, Charles Goodyear subsisted on the little royalties that he received. Bearing ill-health, with his physical strength almost exhausted, he was also supporting a dependant family. Yet, he continued his experiments in his bed, as, for him there was no better experience of personal gratification. He would not sleep till his thoughts and inferences on life saving applications were penned down, occasionally in the middle of the night by his obedient wife Fanny. He would dictate working guidelines and information to men who conducted experiments. After the letters were written and his mind freed, he would be fast asleep.

In the winter of 1859, Charles bought a house in Washington. He stayed in this "quiet home”, as he put it, briefly with his family members. He would often express that life had never been so easy, and that he had never taken so much rest before. Inside the house, a workshop was fitted with a large water bath for testing his life-preserving apparatuses.

When Charles heard that his daughter Cynthia was extremely ill in New Haven on 30th May, 1860, although sick himself, he travelled in a steamer to New York to see her. On his arrival in New York along with his faithful physician Dr. Bacon, he was informed that his daughter had passed away. Charles was too ill to proceed further and stayed back in New York City. From here, Charles tried his best to put together all his business affairs. However, his brother-in law William De Forest was then informed by Dr. Bacon, "This is the last!"

On hearing the news of his terrible illness, Mrs. Fanny Goodyear who was ill too, arrived in New York on 7th June to be besides her husband, who found it difficult to keep on a conversation with her. He would look at his wife with deep, earnest feelings and say, "God knows all". His dying expressions to his wife reflected his gratitude and humble spirit where he forgave all due to whom he had suffered. Twice, he even took parting blessings from all his family members. When citations to his vast and useful work were made during his last hours, his meek response was, "What am I? To God be all the glory." He finally died at the age of 59 on 1st July, 1860, as the morning bells rang for church service on Sunday. This simple, honest and pious man left the world a happy man after gifting the world his invention as he put it, "A man has cause for regret only when he sows and no one reaps."

Charles Goodyear lies buried in New Haven after leaving behind his family with debts of $200,000, though, in due course of time, his five surviving children and wife were comfortably placed with the royalties they received from his invention. The popular ‘vulcanized’ rubber goods now stood as widely used commodities. With the benefits of his hard work now being clearly visible, his family knew that Charles’ divine mission had been successfully fulfilled to bring them a respectable reputation.

Rundown

The rubber business has increased manifold since Charles’ invention. Today, our contemporary lives too have found thousands of commercial uses of rubber. But one cannot forget the endless efforts and countless sacrifices made by Charles Goodyear under trying circumstances to find numerous ways of utilizing rubber in a rapidly industrialized world. He followed his dream with a never give up attitude and patience, despite suffering many family and financial setbacks. His weak business sense too did not put him in a favourable financial position and as a consequence, he faced several embarrassments along the way. Despite his honest and diligent labours, he had to fight lengthy court cases against countless enemies who took him for granted and were always devising schemes to snatch the glory from this rightful owner of the ‘vulcanization process’. Yet, this extremely self-reliant man spent his time, energies and every single resource on his experiments to make India rubber a functional material. Indeed, Charles Goodyear dedicated his life to the study of rubber, and contributed immensely by introducing a new material for arts and diverse applications.

One may think of Charles Goodyear as a mad genius who worked single-mindedly with his obsession. He found over 500 functional uses for rubber and imagined many more. He even devised feasible production processes to scale down the manufacturing costs of mass producing rubber goods at affordable costs. He finally succeeded in rising above his difficulties to give natural rubber that important place of pride among all other types and forms of materials. Charles Goodyear rightfully said, "no one but himself would take the trouble to apply his material to the thousand uses of which it was capable, because each new application demanded a course of experiments that would discourage anyone who entered upon it only with a view to profit."

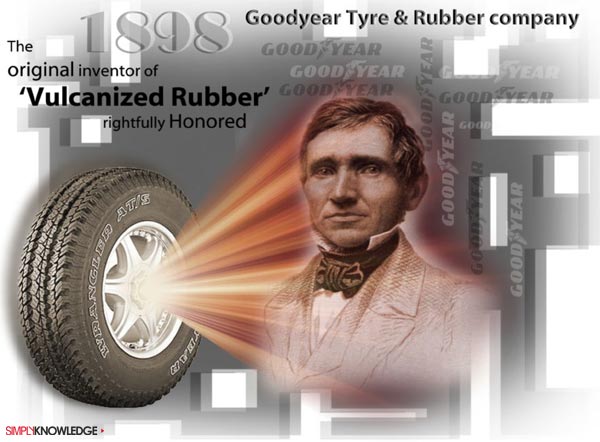

Thirty eight years after Charles Goodyear’s death, Goodyear Tyre and Rubber Company was named after him. Thus the original inventor of ‘vulcanized rubber’ was rightfully honoured and credited. Frank Seiberling was the founder of the company which has its head office in Akron, Ohio. The company which is on an extreme profit making journey, showed sales figures of $23 billion in 2011, and rightfully thanks Charles Goodyear, whose name was selected in February 1976 for the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Charles Goodyear’s life gives us the true inspiring message, “If you fail once, do not be disheartened and don't give up, but keep trying and success can be yours one day.”

Biography of Charles Goodyear | 0 Comments >>

0 --Comments

Leave Comment.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked.