Tags : Industrialist, Tata Power, Tata Steel, Taj Mahal Hotel, Indian Institute of Science

- Text Size +

If you flip through the pages of history known to the mankind, all the upheavals that have been witnessed have primarily been for the sake of money and power. When such a strong desire to grab, hold and expand has been evident since the human being has come into existence, can you imagine anyone who can actually not think of himself and his family, but humanity at large?

In a world where individual survival is the only concern, there rose a man who said, “I will work and give my entire life to serve my country and for the benefit of its people.” He, who actually laid rock-solid foundation for values such as dedication to the cause of humanity, earnest interest in the betterment of all, honesty, integrity and vision to keep up with the changing times even after 150 years. It is his this vision to keep abreast with the changing times and feel the latent needs for the people, without even being explicitly expressed that has made him one of the most fondly remembered person for all of us.

It is only when a person understands your need or desire without even you hinting at it, can the love be called true and pure. One wonders.........................., where do you find such unconditional true love today, which is usually showered by a mother on to her child? But there was a man who loved one and all; each human being with equal love and tender care like a mother...In that case, he can only be called a saint or a wise man.

The man we are talking about here is none other than Jamsetji Tata…the best ever visionary, an astute businessman, an earnest human being, an absolute impartial individual, the man who withheld the corrupt prevalent practices even in a county like India, the one who refused to relent on the trying times and tribulations and above all the most generous spirit…India has ever had.

The man, who envisaged the bright future of the country like India not only for the immediate generation, but for generations to come, while it was still in shambles. As it usually is, for every man, each venture is a transpiration propelled by monetary gain, but here was a noble spirit whose every undertaking, right from salt to software, trucks to airline, water, tea and coffee to even watches and jewellery, each venture was the offspring of the realization emanated from the need of the people of his country. Since for him, the need of people and demand of time were the only concerns to be addressed to, he is aptly revered as the “Father of the Indian Industry”.

When it is but natural for every wealthy man to endow his wealth to his children, can you imagine an empire being built purely on the pillars of deservedness, the strengths, merits and the heart of a person, who can shoulder the responsibilities of the values with integrity, love and care for the humanity. Do you have an idea what would have been the strength of the foundation, which could have vanquished in a few decades as it generally does; but in this case it has only been enhanced and nurtured to the deepest of its roots by the people he had entrusted it with.

He who never believed in charity, made sure that a large chunk of their business income as a Tata Group goes to trusts which have been undertaking various social pursuits for the welfare of the people, for many decades now. Don’t you feel like saluting this man? Yes, each one of us should, and now let us go through the journey of his life and see for ourselves the making of a grand legend…

The Beginning

Jamsetji was destined to enter business, mainly due to the extant tradition of inheritance. His father, Nusserwanji Tata operated a small, trading business in Navsari, Gujarat.

Nusserwanji lived an austere life, peculiar to the priestly caste of Zoroastrians, the ‘Dasturs’. He was reportedly married at a tender age of five years to Jeevanbai, at a mass wedding, since traditional ceremonies were expensive for the cash strapped community.

Jeevanbai Tata delivered their first child, Jamsetji, on March 3, 1839. Jamsetji’s siblings were four younger sisters, Ratanbai, Maneckbai, Virbaiji and Jerbai. Hence, as the sole male progeny, Jamsetji’s taking over his father’s business was imminent.

As the family expanded, Nusserwanji embarked on journeys to manufacturing and trading centres in and around Gujarat to expand the range of products he could sell. Eventually, fortune smiled on the budding entrepreneur when he arrived in Bombay. The port city was the hub of British trade since it had a natural harbour which was vital for freight and passenger liners and a rudimentary railway network. The British colonials had also ensured that Bombay was well connected to rest of India, due to its strategic location that permitted easy access to north and south India.

Nusserwanji entered the lucrative opium trade around 1850, which was licit at the time, since the herbal product was in great demand worldwide. The Western powers prized opium as a medicine for its potent effect of alleviating pain accruing from deadly battle wounds. The British had also won the Opium Wars with China, which provided Nusserwanji, a conducive environment to enter the trade.

Conforming to the Zoroastrian traditions, Nusserwanji had Jamsetji initiated into the faith at a Navjote ceremony. Jamsetji donned the ‘Sadreh’ (an customary undergarment) and ‘Kushti’ (a waist band), in line with the Zoroastrian doctrine, which reminds the wearer of his or her religion and the tenets of ‘ Humateh, Hukteh and Haversteh’ or pious thoughts, speech and actions, as enshrined in the ‘The Zend Avesta’, the Zoroastrian holy book. Jamsetji, despite his education and modern beliefs, wore the ‘Sadreh- Kushti’ till his last days as a reminder of the holy tenets of Zoroastrian he had imbibed.

Jamsetji’s schooling began at a Gujarati ‘gurukul’ (school) in Navsari, where he soon excelled as a brilliant student. Meanwhile, Nusserwanjee had prospered in Bombay. Wanting to further educate his only son and heir, he brought Jamsetji, then 13 years old, to Bombay. Initially, Jamsetji studied at an informal school, but a year later he was enrolled at the prestigious Elphinstone College - one of the rare higher educational facilities in Bombay during the era. Simultaneously, Jamsetji also assisted his father to expand the family business.

During his college days, Jamsetji made several friends, including Dinshaw Eduljee Wacha, who later was a founding father of the Indian National Congress and held prominent positions at the extant Indian Merchants Chamber. Also during his years as student, Jamsetji, then 16, married Hirabai Daboo, a 10-year old girl from a modest Zoroastrian family. In 1858, Jamsetji completed his college studies and was certified as a ‘Green Scholar’- the equivalent of a modern-day graduate.

The year saw the Indian subcontinent in major turmoil. Several small kingdoms were forcibly acquiesced by the British East India Company through force or persuasion. A mixed sentiment of awe and resentment prevailed against the British, who, despite their victories, feared naval attacks by other European powers, especially France, which had allied itself with some Indian rulers. Spurred by a general despair caused by loss of sovereignty of Indian states, British brutalities against the indigenous populace, and systematic destruction of traditional crafts by the colonials, Jamsetji resolved he would do extra efforts to alleviate the sufferings of the locals. He engrossed himself in his father’s business with renewed ardour. He infused new blood and fresh thoughts in the company owned by Nusserwanjee along with partners Kaliandas and Premchand Roychand, making it a highly profitable venture.

A young father by now, with Hirabai giving birth to Dorabji, the couple’s first son, on 27th August, 1859, Jamsetji shouldered the responsibilities of his family and business with equal zest.

Whats in a Name

As, an old proverb states: “What’s in a name?” For the Tatas, it meant everything: a family committed to economic progress, industrialization and modernization of India - a land that had restored the freedom of their ancestors, who fled native Iran in 615 AD, fearing religious persecution.

For the Tatas, India was more than home; it was a sacred place, where the Zoroastrians had established without fear, countless ‘Agiaries’ or fire temples. These places of worship housed fires which were ignited for worship in Iran centuries ago but were never extinguished, in line with the Zoroastrian tradition. These fires had been brought to India using archaic yet effective techniques.

As devout Zoroastrians, the Tatas wished to live the pledge made by Dastur Ardeshir somewhere around 8th Century AD, when these newly arrived, impoverished refugees from the Pars region of Iran sought the benevolence of Jadhav Rana, the king of Gujarat. The king, wary that these migrants could change demographics of his kingdom, showed a bowl filled with milk to the dastur (priest), saying his kingdom was the bowl and subjects like pure milk, which would spoil if any undesirable element was added.

The dastur took the bowl, added some sugar and stirred it. Returning it to Jadhav Rana, he promised the king that Zoroastrians would play the role of sugar - implying, they would only sweeten the local populace. Impressed, Jadhav Rana granted these migrants all rights enjoyed by the indigenous subjects. The Tatas believed in upholding the promise made by the dastur to Jadhav Rana through their work.

The Tatas hailed from the ‘dastur’ or priestly clan of Zoroastrians. It was typical of Zoroastrian migrants in India to assume local names that reflected their place of residence or profession, in line with Indian traditions of surnames. An ancestor of the Tatas was nicknamed ‘Tatar’ or ‘Tatra’ for his Caucasian gait and anger of a Tartar soldier, who were mercenaries in armies of ancient Persia. The title lingered over ages till it evolved into Tata, due to dialectic variations.

Tiny Tots

Tata was destined to become a ubiquitous brand, under the stewardship of Jamsetji. In 1859, the budding entrepreneur expanded Nusserwanjee and his partners’ business by opening a trading centre in Hong Kong - a free trade zone of sorts in the era, thanks to an accord between the Chinese and the British. Shortly after, Jamsetji also made a foray into Shanghai to further bolster the business of cotton, silk, tea and medicinal opiates. However, these ventures proved commercially unviable and consequently, downed shutters. Yet, Jamsetji succeeded in striking relationships with the Chinese merchants and established an office of Tata & Co. during his four-year stay in that country.

Meanwhile in India, Premchand, aged around 30, created a niche in Bombay as a financer, leveraging his expertise to gain credit for trade from banks and merchants. The American Civil War fought from 1861 to 1865 caused an increased demand for raw cotton in Britain and its colonies. Hence, Nusserwanjee’s firm began exporting about 16,000,00 cotton bales to factories in Europe and elsewhere. The company appointed agents in various major cotton growing regions to meet the growing demand while Jamsetji embarked on voyages to expand the business abroad in Japan, France and the US.

In 1863, Jamsetji travelled to England, hoping to establish an Indian bank that could cater to Indian businesses and expatriates. However, the tide was against Jamsetji as the Indian cotton market that had skyrocketed during the American Civil War, simply crashed. During the war, southern US did not produce enough cotton to suffice the demands in England. As a result, they were forced to buy Indian cotton to keep their textile industry running. As soon as the Civil War came to an end, the American South resumed their production and the demand for Indian cotton became almost negligent.

Jamsetji was still on board an England- bound ship and hence oblivious to these upheavals till he reached England. He soon discovered that the bills of exchange that he was carrying were worthless and he was virtually penniless. He went to the heart of London’s financial district, where most of the banks were located, including the Bank of England and the Royal Exchange. He spoke to many bankers and solicitors to help him start up a business. Jamsetji successfully impressed many shrewd English businessmen with his frankness and integrity. As a result, they appointed him as their own liquidator and gave him an allowance of twenty pounds a month, which helped him pay off his creditors.

Of several Zoroastrians that lived in England at that time, two of them played a significant role in shaping Jamsetji’s life: Dadabhai Naoroji and Pherozshah Mehta. They were both students at Elphinstone College and nationalists knighted by the British. They also played a vital part in Indian National Congress. They were actively fighting against the British Colony in India, by being the part of the British political system. They were all followers of William Gladstone, four times Prime Minister of England and also known to be a protector of the poor. Jamsetji also developed a deep admiration for Gladstone, even though he had met Gladstone only once by sheer coincidence.

The Crescendo

The start of Abyssinian War brought back the demand and contract for Indian cotton industry as well as British-Indian Army. General Napier, Commander-in-Chief Bombay, was appointed to go to unknown territories of Ethiopia to fight a war that could last for months. He needed supplies that would last for a year for the 16,000 men he was taking along with him. Nusserwanji’s firm was experienced at executing such contracts and successfully bagged the business. This brought the firm out of their financial crisis.

Post Industrial revolution, the British had become very powerful and Jamsetji was convinced that there was a huge scope to poke a hole and take advantage of the Abyssinian War. Jamsetji moved into the textile industry in 1869 and set his eyes on a broken-down, bankrupt oil mill in Chinchpokli, which was located in the heart of Bombay. The mill was renamed Alexandra and converted into a cotton mill. The cloth being produced in India at that time was very coarse compared to what was being produced in England and elsewhere in the world. Two years later, Alexandra was sold to a local cotton merchant for a fat profit and Jamsetji decided to learn how the English operated their textile industry. After this, Nusserwanji retired and handed the reins of his business to Jamsetji.

After his retirement, Nusserwanji was struck with a serious illness and had to travel to China and Japan for treatment. While in China, Nusserwanji decided to reopen the Hong Kong branch with the help of his connections that were related to the trade industry. They were his brothers-in-law Dadabhai and Sorabji Tata who had gained success in a small but long standing import-export business between Bombay and Far East. Dadabhai had been the chief cashier and accountant in Nusserwanji’s first venture. Nusserwanji placed Dadabhai Tata in charge of his business in China and assigned half the share in business to Jamsetji and himself. The firm thus constituted and continued for several years till Dadabhai’s death in 1876. This is when Jamsetji and his father withdrew their capital.

Power Moves

During the following two decades, 49 cotton mills were started. Towards the mid of 19th Century, India began attracting a lot of investors from all over the world. The development in railway and shipping industry opened doors for India to export wheat, cotton and jute. Suez-Canal was opened which made country much more accessible. Jamsetji studied cotton industry in India carefully and as a whole. He noticed that the major problem that obstructed India to compete with other countries was the irregular rains upon which agriculture depended so heavily.

This was also the time when the British decided to take total control over the overseas trade, thereby drastically affecting the ordinary Indian. By the end of the 19th Century, this export surplus had become a big problem for Britain’s balance of payments. Since the tariff went up in US and other European countries, Britain found it difficult to sell their finished products. Thus, they started selling their finished products in India, which became a captive market for the Lancashire textile industry. Jamsetji saw this as an opportunity to enter the textile market and break this vicious circle created by the English Empire.

On his next trip to England, Jamsetji was amazed at the quality of cotton being produced with skilled labour and machinery at the Lancashire cotton trade. However, the conditions of the people working in the industry were dark and pitiful. Old people were continuously working day and night; children were scrambling for cotton fluff under the howling machines for a penny a day. Jamsetji was confident that the quality of cotton could be replicated in India and he could beat the English textile industry. He was also determined that he would never let the conditions of his workers be so bad.

After doing an in-depth study of the cotton industry, Jamsetji returned to India with an extensive knowledge about the textile industry. He was determined to establish an industrial revolution in India. Bombay was the place to start the industry, but he understood that the textile industry could be best set up at a place which was at a close proximity to cotton fields and had an easy access to a railway junction. Apart from this, the place should be in the midst of a market and have an abundant supply of water and fuel. After much research, he narrowed down a place in the heart of Maharashtra – Nagpur, as this city met all the requirements. Jamsetji acquired marshy ten acre land from Rajah of Nagpur and filled it up with earth.

The operations soon began and Jamsetji restarted the industry on 5th September, 1874 under the title of Central India Spinning, Weaving, and Manufacturing Company. The first general meeting was held on 30th June, 1875. There were about 2,500 share holders and it was declared in this meeting that Nagpur was going to be their place to set up the mill. The land was purchased at Rs. 1,000 per acre and the entire plot was brought for Rs. 8,500. 30,000 spindles and 450 looms were ordered from England. Highly skilled mechanics were called in for training. It was all set to make history in the textile industry. Since Nagpur offered no field for contractors to erect buildings, the work was carried out internally by the departments. Even the raw material was taken care of by the company and only a small portion of material collection was entrusted to small contractors. Quarries were opened to gather and shape stones, cut and design timber and also to manufacture chunam (lime). In total, the company successfully saved twenty-five percent to what it would have cost them in Bombay.

The capital then invested was about 1.5 lakhs. A local banker, who had once refused to loan money to Jamsetji Tata said, “Jamsetji had put earth into the ground and taken out gold.” Jamsetji spent next several years of his life in Nagpur, building and resolving any problems that the men faced at the mill. Jamsetji’s success can be attributed to his keen eye for finding the right men to work with. One of his greatest discoveries was a young Parsee, Bezonji Dadabhai Mehta, a Goods Superintendent on the Great Indian Peninsula Railway. At the time of appointment, Bezonji knew nothing of the cotton industry, but possessed qualities such as common-sense, honesty and experience that greatly appealed to Jamsetji. He trained him for two years and later made him responsible for the mill.

Along with his technical expert James Brooksby, Jamsetji adopted the ring frame technology (used to make yarn). It was much later that this technology became a popular method of textile industry in India and England. This was one of the smartest moves by Jamsetji Tata. This innovation doubled the production, increased the share value and also firmly established Jamsetji’s reputation as an astute businessman, even among his employees. He was a loving and sharp employer who picked his managers very carefully. He was never influenced by family or friends while choosing his workers. He would judge the person’s ability well before hiring him. He made sure that his employees were well trained, had hygienic living conditions and worked in good ventilated space. He did not exhaust or over burden them with work so that they could get enough rest. He offered them good remuneration and performance incentives, provident fund and gratuity. His working space also had a daycare for female employees with children. These facilities were not mandatory in India or anywhere in the world at that time.

It took three years of hard-work and dedication to get this textile plant up and running. Finally, on the first day of the year 1877, when Queen Victoria was being proclaimed as an empress to India, Jamsetji inaugurated his mill, Empress Mills. He was very vigilant and kept close eye on his factories. His passion for innovation and technology was clearly visible in the constant improvement he showed in his mills. Empress Mills also started a Gujarati school for the children of its employees. Dictionary of National Biography has written highly about Tata’s textile mills. It quotes, “Tata Mills were soon recognized to be the best managed of Indian-owned factories.”

By 1880, Nusserwanji decided to again join Tata & Co. inspite of his ill health. Jamsetji was worried about the same and advised him against it. This was the time Nusserwanji felt that the China branch was “too remote for efficient supervision”. In 1884, when the Empress Mill was high on success, two of his family members joined Jamsetji, his son Dorabji Tata and Mr. Ratan D. Tata, whose father was adopted by Jamsetji’s brother. Mr. R. D. was always referred with his initials to distinguish him from Jamsetji’s second son, who was also named Ratan. Jamsetji had a special liking for this kid who had also graduated from Elphinstone College. He adored his ability to make financial decisions and energy with which he worked. R. D. was 30 when he joined Jamsetji and Dorabji was only 25. The son always accompanied his father and had intellectual conversations with him. Meanwhile, Nusserwanji’s health further declined and he decided to finally retire. He breathed his last in 1885, before which he built a Parsee Agiyari (Fire Temple) in Bandra, Bombay, for his wife Jeevanbai.

Svadeshi Mills

Karl Marx, the famous German philosopher said, “The homeland of cotton was inundated with cotton.” Jamsetji noticed that about two thirds of British exports to India were cotton goods. He opposed the use of British cotton goods and started a mill that would make only superior quality textile with Indian cotton. With this objective in mind, he found Svadeshi Mills Company Limited in 1886. Dharamsi Cotton Mill, located in Kurla (near Bombay), was going through severe financial trouble. The mill had destroyed reputation of several agents and because of superstitious reasons, cotton merchants now feared to invest in this mill. Jamsetji saw this as an opportunity and took over the mill, which was much more profitable than expected. He renamed this mill to Swadeshi Mill. Jamsetji could have sold the mill for a whooping profit of Rs. 2, 00,000 within twenty-four hours of its buying but the success of Empress Mills had given him a confidence and he took it as a challenge to recreate Svadeshi Mill. He brought experts from Nagpur to work on this mill. The experts were not in favour of this purchase, but Jamsetji made it very clear that they should only stick to advising and not deciding. He jokingly called this mill, “Rotten Mill”. The situation got worse when financers denied their support. Shareholders were disappointed and Jamsetji was left alone. Nevertheless, he assured everyone that this was one of the best bargains, and he would make the best of it. Despite the odds of theft, shortage of labour, poor machinery, and difficulties in management, the Svadeshi Mill rose to its epitome due to the adroit management of Jamsetji.

Jamsetji wanted his cloth to be finer than British Raj. He researched and imported different strains of cotton that produced longer, finer and softer fabric. He brought Egyptian cotton seeds to India. However, these were difficult to plant and grow in Indian soil and weather. Many agriculturists told Jamsetji that this project was a total failure. Nevertheless, Jamsetji’s determination and persistent nature made sure he was eventually successful in growing Egyptian cotton in Indian soil and climate. He trained the amateurs on the essentialities like right time of sowing, manuring and watering. He was equivalent to what is today known as an agriculture scientist. He even went ahead to publish a pamphlet titled The Growth of Egyptian Cotton in India. He printed yet another pamphlet that explained how the supply of skilled labourers could be increased. In the year 1887, Jamsetji formed the company, Tata & Sons, along with Dorabji Tata and R.D. Tata.

For the love of bombay

It won’t be wrong to claim that Bombay, the city as we know it today, owes its growth and development to this great man Jamsetji Tata. Bombay was an amalgamation of seven islands and local fishermen called it Mumbai. It was only after the Bombay harbour was built that the British started taking interest in developing this city. Jamsetji had a special affinity with Bombay. Fifty years that he spent in the city, he supported, fought, if necessary, with the government to reclaim and prosper the city. When he first came from Navsari, most parts of the islands were covered with tides and mud; drains were choked and roads had filth up to two feet. It was a small city until the mid 19th century. Besides the three gates, St. Thomas Cathedral (Churchgate), Bazaar Gate (Fort, which was insanitary) and Western Gate, Bombay was mostly jungle where British went to hunt foxes. Sir Stanley Reed quotes, When the Chartered Bank had the courage to move a 100 yards to the North, old stager threw up their hands in horror and asked, “Who on earth is going to the jungle to do business?”’

Jamsetji was confident in the development and expansion of Bombay and its suburbs. After coming back from Nagpur in 1878, Jamsetji had settled in Malabar Hill in South Bombay. He bought a lot of land and rapidly started investing in British middle class housing and buildings. During the 1890, he was probably one of the largest landowners in the city and helped immensely in its development. Jamsetji was confident that once railway was built, the city would prosper and people from all around the world would flow in to invest in land, and seek work. He was proved right. A plot he obtained in Bombay for Rs. 30 fetched him Rs.1000 two decades later. He had fascinating reclamation schemes that were carefully planned and drawn with the help of Jamsetji E. Saklatvala, his estate agent. He had mega plans to transform jungles of Juhu into small Venice. Instead of roads, Jamsetji had ideas about connecting islands with canal.

After carefully listening to Jamsetji’s schemes, Mr. Orr, the collector of Thane district advised him to talk to Mr. Ardeshir Wadia. His family was the master builders of the East India Company. They also owned what is now known as Juhu-Vile Parle Inam villages. Although Mr. Orr was in favour of this scheme as it would bring a new look to the city, Mr. Wadia was not easy to convince. Even after Jamsetji offered an attractive rate, Mr. Wadia did not approve of his plans. However, this was not the only trouble; when Jamsetji planned a Mahim River Reclamation Scheme, the army located in the area denied to shift its rifle range to another location. He then suggested that the site should be moved closer to the railway station, but officials objected on the financial need that would be required to make this change. Officials were not the only ones objecting, some local fishermen also denied giving up on their traditional fishing site despite being offered good compensation. The Bandra project too fell apart when the Municipality refused to lease certain grazing grounds. Jamsetji met with nothing but obstruction at the lower level, when he proposed housing schemes. The Telegraph Department objected saying that inflammable material used to build houses would be dangerous to their line. Jamsetji assured them that no such material would be used.

Another scheme that Jamsetji proposed was to move all the milk cattle out of the main city and create an elaborated scientific line of poultry, buffalo and sheep breeding plant. He suggested that 2800 acres of land from Bandra to Mahim, extending up to Kurla, be divided into lands that would develop special fodder for cattle and have clean sheds for milking. He even planned to introduce modernized, fish cold storage which would be stocked with white salmon, red miller, prawns and other kinds of fish for supply. These schemes were not for Jamsetji’s personal benefits. As he wrote in one of his letter to the Governor of Bombay, “Even if the venture should not yield much return, I should still consider myself adequately compensated by the resulting improvement of the value of property in the city where I have large interest in land.” Jamsetji was ready to agree to any terms and conditions that the government would lay down to execute these plans. After facing constant delays and rejections he finally decided to meet the governor.

‘Esplanade – a gorgeous palace’, as one of his English friends would say - was a beautiful home of the Tatas’. For years, Jamsetji had been looking for a suitable residence for himself. Most of the houses available then were congested and in not so nice locations of Bora Bazaar and Parsi Bazaar in Fort area. Jamsetji had changed many residences before, which gave him a good idea of all the possibilities a residence in Bombay could hold. Although a simple man, Jamsetji loved spacious and splendid surroundings. He now wanted to make a permanent home besides the sea. After years of searching, he found a beautiful land right opposite to the sea on Esplanade road near what was known as Bombay Gymkhana at that time. He took this land on a 999 year lease on a reasonable price.

An architect named Mr. Morris was appointed by Jamsetji to build a classic style mansion. The courtyards were to be surrounded by corridors and have a glass roof; patios were to be designed similar to the ones which Jamsetji had seen in Spain during one of his trips. Rooms were supposed to be few in number, but large and spacious. The house had to comprise of a marble staircase and European style furniture. It was a commemoration of curios and memorabilia Jamsetji had collected during his travel. Esplanade Mansion was made close to the business parts of Fort. Bathrooms with water and wardrobes were placed in every suite. The mansion had four floors with four flats on each floor. The terrace gave a beautiful view of Bombay. Mosaic art was created on floors and electric lamps, an innovation then in India, were fitted throughout the mansion.

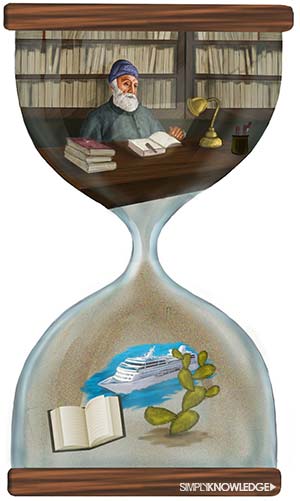

A horse-shoe-shaped dining table was connected to the kitchen and the food was brought in dramatically from the center. The man loved his food. Every Sunday evening he would gather his nephews and family members and indulge in eating ice-cream, which was a rare delicacy then. Jamsetji had a beautiful library in his home. This is where he spent most of his time, reading about literature, travel and botany; this is where new ideas for his business came about, and this is where he thought a lot about his country.

Wah Taj

Jamsetji’s pioneering visions about Bombay did not only remain limited to just his house and the reclamation schemes. He brought an epic change in the city that will be remembered forever. This change was called The Taj Mahal Hotel. Bombay was flourishing because of the cotton boom and got many visitors from all over the world. But the living conditions for the tourists were unfavourable. The houses were cheek to jowl and the rats scampered around the city at nights. Unfortunately for the city, it only had one hotel that could be worthy of calling it so – the Watson’s. Even then, this hotel was far below the European standards. The rooms were small, heat was unbearable, especially with mosquito nets and curtains, and ventilation was horrendous. To add to this disgrace, the hotel did not admit Indians.

There are several theories as to what might have sparked Jamsetji to build the magnificent Taj Mahal Hotel. Some people speculate that Jamsetji was denied entry into the Watson’s and that’s when he decided to build a hotel far better and bigger than Watson’s. Nevertheless, this was a strategic plan on his side to build a spectacular hotel for the guests of this city. It could very well have been what Sir Stanley Reed said, “He had an intense pride and affection for the city of his birth, and when a friend protested against the intense discomforts of the hotel life in Bombay he growled: ‘I will build one.’” Jamsetji took the decision for the foundation of Taj in 1898 without even consulting his friends, partners or family.

Jamsetji built the Taj Mahal Hotel with his personal funds and made sure that the hotel had the best of the amenities from all around the world. He had an exact idea of what the hotel on completion should look like. In a letter written to his son Dorabji, Jamsetji elaborated on the ideas he had for this hotel thus, “The Hotel, when completed, will be five storeys high, and will accommodate, besides boarders to the number of 500, a number of permanent residents. Immense cellars, below the ground floor level will contain the refrigeration plant, which will cool the rooms of the inmates, and will also enable their food to be stored in a manner foreign to India.” The spun steel pillars in the ball room came from a Paris exhibition, whereas, the soda bottling plant, electric laundry, and fans were imported from USA.

Jamsetji kept a close watch on costing for each of his projects, but not on this hotel. This was to express his love for the city, just like the original Taj Mahal was built by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan as an expression of his love for his wife Mumtaz. Jamsetji made arrangements with a German firm to carry out the electric work for his hotel at a cost of two annas a unit. The kitchen, cellars and service was relevantly new. For a luxurious feel, the hotel provided a Turkish bath, a post office, a resident doctor and a chemist shop; all of which were just a call away.

On the inauguration of the monumental hotel on 16th December, 1903, people came from all over the world to see the first building to be illuminated with the new innovation of electric lamps. Hundreds of servers and attendants waited for their guests to arrive. Interestingly, when Jamsetji’s sister heard the story of him building the Taj Mahal Hotel, she commented in Gujarati, “What? You want to build a science institute in Bangalore, a great iron and steel factory, a hydro-electric plant and now a Bhattarkhana (an eating place)!”

reaching the shores with shipping

In his lifetime, Jamsetji gave most attention to three projects: Cotton, steel, and education of sciences. Once the cotton mills were taken care by Mr. Bezonji and his sons, Jamsetji could now think about his other passion projects. To start with, he carefully planned all his wealth and made sure that not only his family, but majorly all of India would be benefitted. A big portion of his income was allotted to education and if there was any surplus, he would invest them in industrial experiments. His projects often failed. But to a great man like Jamsetji, failure was just a stepping stone to success. He would turn his mind to other projects that would show his patriotism.

One such revolutionary step that Jamsetji took changed the way the shipping industry worked in India. Jamsetji noted that while exporting to his company’s branches in China and Japan, there was a heavy freight charge. This was because the routes were monopolized by three companies, Austin Lloyd, Rubbatino Company, and Peninsular and Oriental Company (P&O), which was the biggest among all. After entering the business he became aware of the advantages derived from the ‘invisible exports’ of a carrying trade and decided to start his own line of steamers. He had a fair idea of the challenges that were going to come his way.

A few years before, Jamsetji had fought the high rates but was beaten. This was because, the two companies he most relied on, deserted him. They further backstabbed him to get into an agreement with P&O. The export of cotton increased to China and Japan. The three companies took an advantage and raised their charges even further to Rs. 13 and Rs. 19 per cubic ton.

Jamsetji turned to the director of a Japanese steam navigation company called Nippon Yusen Kaisha that offered him to compete with trade in China only if he agreed to equally invest in the scheme. Jamsetji agreed and an agreement was signed between the N.Y.K. (Nippon Yusen Kaisha) and Tatas for the carriage of the Indian cotton goods at cheaper rates. During his travel to England, the idea of starting a shipping company started taking shape in Jamsetji’s mind. He chartered an English vessel, Annie Barrow, and suggested his son to name the company Tata Lines, the only time he ever suggested naming the project after his company.

Jamsetji never liked his steamers to be idle even for a day. Tata Lines guaranteed many sailings a year, unlike the three weeks’ service that was otherwise offered. Soon enough, two ships from Tata Lines, Annie Barrow and Lindisfarne, as well as two Japanese vessels were docked to start this new line. They offered a competitive Rs. 12 per ton of 40 cubic feet. Tremendous praise was received from everywhere, but it was short lived. The rivals were quite strong. P & O lowered their price to Rs. 8 and offered free shipping of cotton to Japan. These offers were in form of rebate, only if the shipper signed a declaration that they were not interested in any shipment between Japan, China and Bombay in NYK or Tata Lines vessels. The Lindisfarne was inappropriately reported unfit to carry a cargo of cotton. Jamsetji had seen P & O do this before. The company would lower their rates until the rival was out of business and then raise it again. He was disappointed with the unfair trade methods that the competitors were using and addressed the same to the Secretary of State for India.

The Japanese Cotton Buyers’ Association kept their side of the bargain but unfortunately, Jamsetji’s Indian friends deserted him. One after the other, cotton merchants from Bombay withdrew their contracts. Numerous letters were circulated to state that Tata Lines was not started out of patriotism but rather selfish motives. Once again Jamsetji was beaten. He tried explaining the merchants about P&O’s strategy, but no one gave him an ear. Finally, he had to withdraw his line.

Another venture undertaken by Jamsetji was to export mangoes. After travelling the world Jamsetji realized that Indian Alphonso mangoes were relished throughout the globe, especially in Great Britain. Jamsetji would always study the project and consult experts before embarking on a new one. So he did with this one too. P & O had been experimenting with carrying fruits. Jamsetji realized these experiments were unsuccessful and unprofitable, hence he dropped the idea. Another venture that never went through was that of water supply.

Institute of science

While establishing and working on his other projects, Jamsetji faced difficulty to recruit satisfactory subordinates. Travelling in Europe and America had convinced him that the application of science to industry was one of the greatest needs in India to mitigate famine and pestilence, if not eradicate it completely.

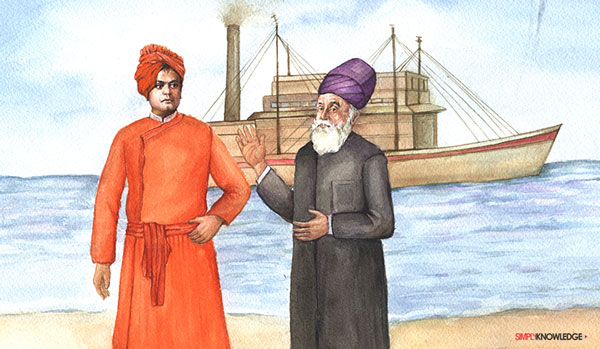

Many of the nationalists regarded English education as exotic. In one of the letter to Swami Vivekananda, who supported Jamsetji in his endeavours, he wrote, “I trust, you remember me as a fellow-traveler on your voyage from Japan to Chicago. I very much recall at this moment your views on the growth of the ascetic spirit in India... I recall these ideas in connection with my scheme of Research Institute of Science for India, of which you have doubtless heard or read.

Universities then were only examining bodies and the teaching was done in colleges and schools remotely located, sometimes even hundreds of miles in distance.

Jamsetji valued education the most. In 1892, he started a scheme, wherein he would chose a few students and send them to England. Jamsetji did not believe in charity, hence he gave students a loan on very nominal interest. He wanted to build an institute where students would be given generous choice of subjects, opportunity to complete their studies in Asia and ample of provision for fellowship. Jamsetji wanted to generate a spirit through reading, examination and tutorials that would change the way East was looked at. Such an elephantine task needed a good assistant. Mr. Burjorji Padshah was just the man Jamsetji was looking for. He entrusted Padshah with the responsibility of selecting professors for this mammoth mission.

For quite some time now Jamsetji had been thinking about making an Institute of Science. When Jamsetji put his proposal for building The Institute of Science for the first time, Lord Curzon, the then Viceroy of India commented, “Where are the students to qualify to join it, and where are the opportunities for their employment?”

Lord Curzon just laughed at Jamsetji’s proposal and thought that his plans would never succeed. However, Jamsetji was not discouraged and he kept looking for suitable sites for his upcoming Imperial University, the name he had decided upon. In 1895, he tentatively settled on Bangalore as he felt that Bombay might not be able to spare the land and climate required for such an institute. Besides, Maharajah of Mysore had offered 300 acres of land in Bangalore, Rs. 5 lakhs towards the cost of building the institute and an annual subsidy of Rs. 1 lakh. Jamsetji, however, did not get the necessary clearance from the government.

Although Imperial University was an attractive name, some people did raise objection to it and after much speculation, the name Indian Institute of Science was finalized. In a conference in Simla, it was suggested that preference should be given to science and technical field, while philosophical and educational branches should be left out. And so it was done. Mr. Ramsay from India, who was writing a report on this institute for the government, was introduced by Jamsetji to many Indians who were well versed in languages, literature and antiquities, so as to push the other side of study. The progress of the university was constantly delayed, but Jamsetji never abandoned the project.

the steel man of india

In his library, Jamsetji kept one of his most treasured possessions, a scrapbook. The first sentence of this book was a quote by the famous thinker Thomas Carlyle, in a speech he had made in Manchester in 1867, “The country that has the steel has the gold.” For seventeen years Jamsetji kept a track on the news about minerals in India in this scrapbook. Few years back Jamsetji had read a report by a German geologist named Ritter Von Schwartz, on the availability of iron ore in Chanda District in the Central Provinces. This gave him the core idea to set up a steel industry. He took samples of soils which had coal and iron from Warora city and Lohara, and carried them to Germany for testing during one of his trips there. However, the samples were rejected as they were found unsuitable.

In the year 1899, Major Mahon’s report stated that India was ready for the steel industry, and good quality coal from Jharia coalfields in eastern India and iron ore from Chanda and Salem District could be used to manufacture steel. Just then, Lord Curzon decided to liberalize the licensing system. Jamsetji took a chance at the project but instead of going to Lord Curzon he decided to go straight to the Secretary of State for India in London, Lord George Hamilton. Though Lord Hamilton was apprehensive regarding the quality of iron ore, yet, he gave Jamsetji the permission to go ahead with the project. Jamsetji immediately applied for licenses in Lohara and Peepulgoan areas of Chanda District. However, Lord Curzon was still skeptical on India pulling off such a massive project and therefore, appointed British industrialist, Sir Ernest Cassel to see the viability of the steel plant project in India.

Initially, this project was just a one-man show, although Jamsetji kept his son informed about the progress. He visited USA to investigate and collect further knowledge and information which would be useful for his steel project and visited every area that was rich in coal, iron and limestone. He established a small office in New York that collected data for him. The American system of working and the locations influenced Jamsetji a lot. In a letter that followed to his son, he mentioned, “Be sure to lay wide streets planted with shady trees, every other of a quick-growing variety. Be sure that there is plenty of space for lawns and gardens, reserved large areas for football, hockey and parks. Earmark areas for Hindu temples, Mohammedan mosques and Christian churches.” One can very well judge Jamsetji’s concern for environment and sports from this letter to his son.

One of the most crucial men that made this plan successful was Mr. Charles Page Perin, who had a very interesting encounter with Jamsetji. As he describes it, “I was poring over some accounts in the office when the door opened and a stranger in a strange garb entered. He walked in, leaned over my desk and looked at me for a full minute in silence. Finally, he said in a deep voice, ‘Are you Charles Page Perin?’… I believe I have found the man I have been looking for… Will you come to India with me?” Charles was ‘dumbfounded’ but accepted Jamsetji’s proposal and sent his partner C. M. Weld to start with.

Due to failing health of Jamsetji, who was now above 60, his son Dorabji was requested to take over the project. He noticed a dark area near Durg District on a colourful map he was presented. On further inquiry he found a report prepared by an Indian geologist, P. N. Bose, fifteen-years ago which claimed about rich resource of iron in the district of the Dhalli-Rajhara hills. Dorabji and Weld immediately visited the place. The work then continued to establish the company, which was popular as TISCO (Tata Iron and Steel Company) and now known as Tata Steel. The company today employs about 80,000 people and is listed in Bombay Stock Exchange as well as National Stock Exchange. The key plant is in Jamshedpur, Jharkhand and the company is recognized as the world’s best steel producing company.

Powering India with Hydro-electricity

In 1757, Daniel Joneaire, a Frenchman, had the first successful experiment with hydro-electricity, six years before the first hydro-electric plant that was built on Fox River, Wisconsin in 1882. Jamsetji too wanted to explore the opportunities with hydraulic energy starting with the Empress Mills. For the same he examined the waterfall in Jabalpur. Jamsetji was eager to develop this plant but it failed as a fakir had been living there and the government was of the opinion that moving him might hurt the sentiments of his large-number of followers. As a second option, Jamsetji thought of Doodhsagar Falls at borders of Goa. He thought the energy generated there could be supplied to Bombay. But since Goa was a Portuguese territory and the power was to be supplied to British territories, he dropped the idea.

Meanwhile, an enterprise had set up their hydro-electric plant in Darjeeling to support their tea estates. The owner, David Gostling was exploring the Western Ghats of Lonavala and Khandala for possibilities of hydro-electricity. Jamsetji was initially doubtful about supplying power from Western Ghats to Bombay as he thought that the distance was too long. But after his visit to England, he realized that hydro-electricity was developed to be supplied over long distance. The scheme was kept a ‘secret’ from the Indian government, as he thought that the government might think about the distance as a drawback and try to abeyance the project.

Jamsetji met Lord Hamilton again in November 1902 to speak to him about his project for an institute and a steel plant. During the conversation he did manage to put forth the hydro-electric proposal in brief. A month later, Jamsetji followed up with the proposal which stated that he had keen interest in Bombay Telephone Company and that the Brush Company of London had left no place for him to build new electricity lines. He requested Lord Hamilton to consider his proposal for electricity that would be supplied at not more than a quarter of the price Brush Company of London was charging. Lord Hamilton was quite responsive and said, “If Tata was successful it will bring tremendous pride to the country”.

Jamsetji’s hydro-electric plant got a lot of support and interest. The concept of artificial waterfall that Jamsetji had proposed to generate electricity fascinated Lord Sydenham, who was also an engineer by profession. His small scheme was enlarged to three artificial lakes to make sure there was never shortage of water. Two of the biggest mill owners supported the scheme and offered to convert their mills from steam powered to hydro-electric power.

towards the end

As Jamsetji reached the age of 65, his health took a turn for worse. He could no longer digest his appetite, sleeplessness conquered his nights, he had difficulty in breathing, and was down with dull pains of dyspepsia. Contrary to what was advised to him by medical experts, Jamsetji never gave rest to his body and mind. He left for Cairo in early months of 1904. After a month’s stay, he left for Naples to visit a doctor on Dorabji’s request. It is here that he received the news of his wife’s death. She had been sick for some time and scrummed to a paralytic attack. As a tribute to his wife, Jamsetji founded a fund for midwives in Navsari.

By second week of May, Jamsetji moved to Germany with his family doctor where he was joined by his cousin Mr. R.D. Tata. This is when Jamsetji spoke to him about his aims that had activated his life, and expressed his wish that the same be followed by his sons. He said, “if you cannot make it great, at least preserve it. Do not let things slide. Go on doing my work and increasing it, but if you cannot, do not lose what we have already done.”

Jamsetji knew he was dying and wished to see his sons now. He called for Dorabji who arrived on 18th May, but by this time Jamsetji was in a comatose stage. He died the following morning on 19th May. The news reached Bombay and after the third day the Oothuman was held in the presence of 400 Parsee, mostly of the Priestly class. A high Priest of Navsari recited the prayers and commemorated Jamsetji Tata’s death. An issue regarding his burial was raised as to mummify a body was against the Parsee religion. Hence, Dr. Row injected a preservative prepared by a German in Jamsetji’s body. The body was then taken to England and on 24th May, the remains were placed in a coffin and lowered into the ground following all the rites of the Zoroastrian religion. The funeral was attended by Dorabji and his wife, Mr. R.D. Tata, his nephew Mr. Behram and a few English friends. His grave lies in the cemetery at Brookwood in a Persian style tomb.

the man behind the curtains

Jamsetji though a simple man, always loved to display new technology on Indian streets to make the commoners aware. When he was 60, he was one of the most prominent men in India. He always thought ahead of his time. His stature and wealth never got into his head and he remained sensitive, sympathetic and sincere. It is easy for a businessman to recruit employees, pay them a salary and consider to have amended to his responsibilities, but for Jamsetji, it surely was not so. He believed in equality, absolute integrity, awareness of the welfare of the society and giving equal opportunity to people with calibre.

He was of the belief that both, education and athletics, had equal importance. He had a big role in the establishment of Parsee Gymkhana and was also a founding member of Wallingdon Club, where intellectual people from Europe and India gathered to discuss various matters. He was the centre of three generations. His father was a friend and a philosopher to him, while he was the same to his sons. Later in life, however, the man preferred staying aloof, stern and unbending. He often visited his other homes in Navsari, Ootacamund, Panchgani and Bangalore where he would conduct agriculture and animal breeding experiments.

The development scheme of Bombay that Jamsetji had proposed, received a zealous interest from his second son, Ratanji Tata. He developed interested in art and philanthropy and hence, Jamsetji encouraged him to take his development schemes of Bombay further. The formally known as Prince of Wales Museum is a classic example of his love for art. For Jamsetji the purpose came before the team. He had no jealousy for other successful men. He had spotted talent in his maternal uncle’s son R. D. Tata and made him a key partner in his empire. R. D. continued his business in Far East and was one of the earlier Indians to venture into Japan. Jamsetji also supported R. D. to marry outside their community which was a rare thing for Parsees in those days. Jamsetji carefully nurtured Dorabji and R. D. at every stage. Had he not done that, the Tatas would have been very different today.

the Tatas Now and Forever

Growth and prosperity followed the Tatas in every endeavour they undertook. They went to Darjeeling, and India got its first Darjeeling tea. They noticed iodine deficiency in people and to eradicate the same they started Tata Salt in 1983; the first of its kind, using vacuum evaporation technology. This not only met the daily iodine needs of a poor man but was also a hygienic production. Thus the name was given “Tata Salt - Desh Ka Namak”.

It has always been the aim of the Tatas to think about the welfare of people above any monetary gains or loss. Once, when Ratan Tata saw a family of four riding on a bike, the concern about the safety of the rider, or the plight of a commoner to afford a four wheeler to ride with his family, forced him to come out with an automobile that was well within a common man’s budget and could also provide complete safety. This cogitation gave birth to the automobile ‘Tata Nano’- the first low priced car. Furthermore, as per the latest rumours in January 2013, in an attempt to hold competition against auto leaders for well within budget cars, like Alto 800, Eon and so on, Tata engineers are working upon an 800 cc version of its “worlds cheapest car”, the Tata Nano. Not only this, taking into consideration the every rising price of petrol, by mid of 2013 they intend to launch ‘Tata Nano CNG’ version, followed by the diesel version by end of the year.

It is natural for any businessman to endow his wealth to his children, but for the Tatas it has never been about blood relations or family hierarchy. For them it is always about the capability of a person and his ability to carry forward their values and thoughts. Hence as said by Ratan Tata in an interview, ‘he was happy not being married and handing over the chairmanship to a person who in every sense was worthy of it.’ And finally after 15 months of rigorous search, he chose Cyrus P Mistry as the next torchbearer of the Tata Group. Cyrus Mistry’s father, Pallonji Mistry is the largest share holder in the Tata Group. It is the second time in the company’s history that a non - Tata is heading the group; the first time being when Sir Nowaroji Saklatwala led the group between 1932 and 1938.

As of today, the Tata Group is a multination conglomerate, with operations in more than 80 companies across six continents, 114 companies and subsidiaries, boasting revenue of USD 83 billion, of which 65.8% is held under charitable trust. The total market capitalization of the Tata Group as on April 18, 2013 is valued at Rs. 499,337 crore/ $92.52bn. In the corporate world, each and every organization thrives to magnify their valuations, yet, here is a group which has never bothered to undergo a revaluation process? Why it holds such a great significance in this case is because the Tatas have the lands and properties situated at the most prime locations throughout the country, which if revaluated, can make them the numero uno group of companies in the world overnight. But encashing the benefits for their corporate gains has never been their philosophy. Hence, it indeed lends them the title of the best organization which has survived the umpteen tornadoes of economic and cyclical ups and downs befalling their way, with utmost honesty, transparency and integrity. And the credit for this benevolent and selfless vision goes to this man Jamsetji Tata, who laid a rock solid foundation of ethics, moral values and meticulous way of functioning.

Tata Group is probably the only company whose core values are proudly defined and mentioned by each and every employee:

Integrity: We must conduct our business fairly, with honesty and transparency. Everything we do must stand the test of public scrutiny.

Understanding: We must be caring, show respect, compassion and humanity for our colleagues and customers around the world, and always work for the benefit of the communities we serve.

Excellence: We must constantly strive to achieve the highest possible standards in our day-to-day work and in the quality of the goods and services we provide.

Unity: We must work cohesively with our colleagues across the group and with our customers and partners around the world, building strong relationships based on tolerance, understanding and mutual cooperation.

Responsibility: We must continue to be responsible, sensitive to the countries, communities and environments in which we work, always ensuring that what comes from the people goes back to the people many times over.

The legend called Jamsetji can very well be understood in the words of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru

“When you have to give the lead in action, in ideas — a lead which does not fit in with the very climate of opinion — that is true courage, physical or mental or spiritual, call it what you like, and it is this type of courage and vision that Jamsetji Tata showed. It is right that we should honour his memory and remember him as one of the big founders of modern India.”

Biography of Jamsetji Tata | 1 Comments >>

1 --Comments

Leave Comment.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked.

These are actually wonderful ideas in regarding blogging. You have touched some nice points here. Any way keep up wrinting.