Introduction

“Out of suffering have emerged the strongest souls;

The most massive characters are seared with scars.”

The life and journey of Kahlil Gibran can be regarded no less than a fictional masterpiece. Mentioned above is one of his own quotes that held true to his life. This man created for himself a name and place in the history of art and literature in spite of living in adverse circumstances and many hardships. His was a journey from rags to riches. Apart from being a renowned 20th century Lebanese-American artist, essayist, novelist, philosopher and theologian, he was also the third most popular poet of all times after Shakespeare and Lao-Tzu. He is mainly known in the English literary world for his 1923 book, “The Prophet”. It is a collection of philosophical essays in poetic English prose and a best-seller that has been translated to more than twenty different foreign languages.

Kahlil went on to become the most popular among the ‘Mahjar poets’ (immigrant Arabic writers). However, he was also regarded as a literary and political rebel in the Arab world as his style of writing, especially prose poetry, distinguished itself from the old classical school. No wonder, that even to this day he is considered a literary hero in Lebanon.

Here is a peak into the life of this literary genius whose fame and work extended way ahead of the Arab world, and became one of the most legendary figures in the history of art and literature.

Familial Background

Kahlil Gibran was born on January 6, 1883, to the Maronite (a pre-Arab Semitic Christian ethno religious group in the Levant) family of Gibran, in Bsharri, a mountainous area in Northern Lebanon (then part of Syria and the Ottoman Turkish Empire). He was baptized in the Maronite (Eastern Rite) branch of the Roman Catholic Church and was named after his paternal grandfather as “Gibran Khalil Gibran”. He was the oldest child born to Khalil and Kamila. Gibran’s father was the third husband of Kamila, who was the daughter of a Maronite priest. She was thirty years old when she delivered Gibran. She also had a son named Butrus(nicknamed Peter) who was six years older than Gibran, from her first marriage to her cousin, Hanna Abdel Salam Rahmeh.

After Gibran, Kamila had two more daughters, Mariana and Sultana. Khalil was deeply attached to his mother and both the sisters throughout his life. His mother came from a very prominent religious background, and this infused her with a strong fortitude that later helped her raise her family independently on the US soils. Khalil never received any encouragement from his father but he shared a very intimate and understanding relation with his mother. She was a pillar of strength for him and always motivated his artistic inclination. Though she was uneducated, yet, she had an artistic talent for music. Khalil’s initial education was from her at home itself. She was a smart lady who was familiar with many languages and could speak Arabic, French and English.

Living in the lush area of Bsharri, Khalil grew up to be a pensive and lonely kid who enjoyed the greenery, the waterfalls, the rocky cliffs, the green cedars and the scenic beauty around him.

One can see the reflection and influence of this resplendent flora in his writings and paintings. He had fallen off a cliff when he was ten years old which left him with a wounded left shoulder that remained weak for the rest of his life. This incident got forever marked in his memory, as he considered this similar to the symbolic event reminiscent of Jesus Christ’s wanderings in the wild.

Khalil’s family lived in underprivileged circumstances, and to add to their miseries, his father’s irresponsible ways further led them to poverty and suffering. Moreover, the isolated village that they stayed in, hardly included any material comforts. These were some of the reasons why Khalil received no formal education during his childhood days. Nevertheless, he received a strong spiritual heritage from the legends and biblical stories handed down through generations. The limited learning that he received was from his village priest whom he visited regularly. The priest acquainted him with the Bible, the fundamentals of religion and languages like Syriac and Arabic. He observed Khalil’s inquisitive and attentive nature and thus began educating him with the basics of alphabet and language, revealing to Khalil the world of language, history and science. In addition to the basic education received from the priest, Khalil was also greatly influenced with regards to education by Selim Dahir. Not much is known about this man, only that he was a doctor and the most learned man of the village. He is said to have taken Khalil (who was less than 10 years old), under his wing, encouraged his artistic aspirations and familiarised him with the world of books.

Dahir always encouraged Khalil’s curious nature that emerged from his intense and sensitive intellect. Khalil’s father used to work as a clerk in his uncle’s apothecary shop, but heavy debts due to gambling forced him to leave this job and work for a local Ottoman-appointed administrator. But the worst was yet to come! Due to severe complaints from the subjects, the administrator was eliminated and his staff was probed. Khalil’s father was arrested for suspected fraud and their family property was confiscated by the Ottoman authorities. Helpless and homeless, Khalil’s mother ,Kamila and her children took shelter with some relatives for a while. Though Khalil’s father was released in 1894, Kamila had already made up her mind by then to shift to the US and seek a better life there. Khalil was uncertain about immigration and therefore everyone except for him embarked on their voyage to the new shores of New York.

Exploring a New Ray Of Hope In the U.S

On June 25, 1895, Kamila left Lebanon with Khalil (who was 12 by then), Marina, Sultana and Peter, and got settled in Boston’s South End, Massachusetts. She joined some relatives there and shared a tenement in Oliver Place. Being in an altogether diverse cultural environment, Kamila was glad that she was at least living in a familiar community that followed Arab customs and spoke Arabic. During those days, it was the second largest Syrian/Lebanese-American community in the US. She now had other responsibilities added to her kitty. From being just a homemaker she was now the bread-winner too of the entire family. Syrian immigrants, in those days, were negatively pictured because of their unconventional Arab ways and supposed redundancy. Hence, peddling was the chief source of income for most of them. She followed suit and worked as a seamstress peddler, selling lace and linen material door-to-door.

Meanwhile, among her four children, Khalil got the opportunity to attend school. His mother wanted him to imbibe formal education which his parents had failed to receive. Thankfully, the charitable organisations in the underprivileged regions allowed the children of immigrants to attend public schools and keep them from wandering on the streets. Nevertheless, forbidden by the Middle Eastern customs and financial hurdles, his sisters were not granted entry in the school. Consequently, in his later life, Khalil Gibran came to defend the cause for women’s education and liberation.

Khalil’s mother’s untiring hard work not only helped the family improve their financial condition, but also enabled them to establish a goods store for Peter on Beach Street, and that too just within a year of arriving. Both the sisters, Mariana and Sultana also started working there. The emotional and physical distress that the family faced brought them closer to each other. Kamila was more inclined towards Khalil who had become considerably remote from a social life. She tried her best to help him overcome his reticence, and gradually he began fraternising with the social life in Boston and exploring its world of art and literature.

Schooling and Education

On September 30, 1895, just two months after reaching the US, Khalil began his schooling in “Quincy Public School”. However, as he had no prior education, the school officials placed him in a special class for immigrant kids to learn English right from the basics. In school, a spell error that occurred during his registration changed his name forever to Kahlil Gibran from Gibran Khalil Gibran. Repeated efforts to restore his former name went in vain. Hence, for his works in English he used the shorter name ‘Kahlil Gibran’, and for his writings in Arabic, he used the name he was baptized with – ‘Gibran Khalil Gibran’. During the two years that he studied in the public school, he scored higher than his American classmates. This was when his teachers began recognising the genius in him.

He also joined an art school nearby – “Denison House”, a settlement house sponsored by the “College Settlement Association” and staffed by volunteers from “Wellesley College”. A turning point in his life came when Kahlil caught the eye of Florence Peirce, an art teacher at the settlement house. She found his sketches and drawings very impressive – a hobby he had nourished from his childhood days in Lebanon.

She brought him to the attention of Jessie Fremont Beale, an influential social worker and coordinator of the BCAS (Boston Children’s Services Association) home libraries project. Beale, in turn, wrote to Fred Holland Day, who was an artist, publisher and a pioneer in photography, which was then a budding art-form in America. She was confident that she could count on him to guide a young talent with artistic promise. She also mentioned that with the kind of aptitude Kahlil showed in his art class, Peirce felt, that if provided with proper artistic education, he could earn a better living rather than peddling on the streets.

In December 1896, 13 year old Kahlil met Fred Holland Day, and from here began his journey to fame and artistic recognition, with the latter introducing him to Boston’s cultural world.

Fred influenced and inspired Kahlil in his creative endeavours. In spite of weak Arabic and English, he turned out to be a quick learner. Apart from educating him on art, Fred was instrumental in boosting his self-respect and confidence. He introduced Kahlil to Greek mythology, world literature, contemporary writings, photography and the writings of “Maurice Maeterlinck”, a Belgian playwright, poet and essayist and “Walt Whitman”, an American journalist and poet. After reading a book given by Fred, Kahlil voiced his first religious beliefs, “I am no longer a Catholic: I am a pagan.”

Kahlil with his large bright eyes, striking features, full lips and his soulful and exotic looks, was also made the photographic subject of Fred’s camera. Apart from this, Fred constantly encouraged Kahlil to improve his drawings. His passion and support helped Kahlil develop his own unique style and technique. Eventually, in 1898, Fred made Kahlil sketch cover designs for “Copeland and Day”, a publishing firm co-founded and self-financed by the former. Gradually, Kahlil stepped into the Bostonian circles and his artistic talent led to his initial tryst with fame at a very early age.

Fred held one of his photography exhibitions in 1898, which had some photographs of the fifteen year old Kahlil as the model. The exhibition received a very good response that further allowed Kahlil to gain a foothold in the Boston society. He was introduced to 24 year old Josephine Preston Peabody, an American poetess and dramatist, whose beauty and cheerfulness attracted Kahlil.

By 1898, Kahlil had completed his elementary schooling. His family felt that he should go back to Lebanon to complete his education and absorb his tradition and heritage, rather than the western aesthetic culture. He could speak Arabic fluently but could not read or write the language. He too felt the need to develop his knowledge on his native language and familiarise with Arabic erudition. However, before he took leave, he sketched a picture of Josephine with the words ‘To the dear unknown Josephine Peabody’, and requested Fred to give it to her.

Return to the Native Land : Lebanon

Kahlil reached Beirut, back home where his father resided, in August 1898 and acquired admission at "Madrasat-al-Hikmah(The School of Wisdom)", founded by the Maronite bishop Joseph Debs. The college offered a nationalistic syllabus biased to Church writings, history and liturgy. Being the stubborn and determined boy that he was, Kahlil wanted the curriculum offered to him be tailored to his personal liking. He demanded an individual syllabus that catered to his educational needs and he spoke to Father Yusuf Haddad, a well-respected senior member of staff regarding the same. Kahlil complained to him that although he had already completed his studies in English, yet, he had been transferred to the elementary class. He added, that he had come to Lebanon to study the literature and the language of his country, to be able to express his thoughts about these subjects in his writings. Father Haddad tried explaining him that learning was like climbing a ladder and one must climb each rung, one at a time. To this Kahlil retorted, “Does not the teacher know that the bird does not ascend a ladder in its flight?” This attitude indicated his rebellious nature which only grew with the passage of time. However, Father Haddad was impressed with Kahlil’s determination and therefore, he met the principal to argue Kahlil’s case. Finally, after much persuasion the principal permitted Kahlil into the school on the latter’s own terms.

Kahlil was fascinated by the style and writing of the Arab-language Bible and got himself engrossed in it. Under the supervision of Father Yusuf Haddad, he read the Arab classics and the translations from the French and Syrian novelists and poets. His classmates and teachers were impressed with the new boy in class. They liked his confidence, rebellious, eccentric and individualistic nature, and even the unconventional long hair. But the school’s strict disciplined ambience and dogmatism disappointed Kahlil. So, he brazenly disobeyed his religious responsibilities, skipped classes whenever he wanted and drew sketches – mostly caricatures of teachers – in his books. In the meantime, Kahlil’s relationship with his autocratic and temperamental father hit the rocks and the latter’s constant hostility towards Kahlil’s artistic talent resulted in an argument, with Kahlil leaving the house to stay with one of his cousins. He had to live in pitiable conditions once again, something that he had loathed and was embarrassed of for the rest of his life.

On the brighter side, a romantic liaison was budding between Kahlil and Josephine, the poetess whom he had met in the US.

Three months after he reached Lebanon, he received an unexpected letter from her saying that Fred had showed her many of Kahlil’s drawings and that she was extremely impressed with his work. On February 3, 1899, Kahlil wrote back to her expressing his delight on receiving her letter. This correspondence via letters continued for almost nine years. With this relation, Kahlil experienced all the facets of love; bliss, pain, grief and disappointment.

In 1900, the 17 year old Kahlil began drawing pictures of the great Arabian thinkers that he was studying. Until then, there weren’t any portraits of them that existed. In his final year at college, he met Joseph Hawaiik, with whom he started a student literary magazine called “al-Manarah (The Beacon)”. Kahlil did the editing as well as the illustrations for the magazine, and later on was elected as the college poet. After graduating from college with flying colours in 1902, Kahlil travelled all over Syria and Lebanon visiting historical places, ruins and relics of the old civilization. However, miseries never left Kahlil. Apart from the dismal conditions that he had to adjust in Lebanon, the news of his family’s looming ill health disturbed him further. In March, the same year, upon hearing of his sister Sultana’s severe ill health, Kahlil left Lebanon, never to return again.

Loss of Loved Ones

Unfortunately for Kahlil, he reached Boston not early enough to see his sister Sultana alive. She died on April 4, 1902, at the young age of just fourteen. Kahlil had loved his family intensely and at the time of mourning for his deceased sister, Fred and Josephine stood beside him as a pillar of support and distracted him by means of artistic shows and meetings at Boston’s artistic circles.

Kahlil was gradually getting more and more attached to Josephine and was madly in love with her though the latter was considerably elder to him. He considered Josephine a guiding light in his life as an artist, and she in turn constantly referred to him as ‘her young prophet’. This love, however, was only one-sided as Josephine later claimed to be only a friend or fellow artist to Kahlil. Nonetheless, she introduced him to prominent people as she believed he was a genius. It could have been mere infatuation from her side or the difference in their ages that forced Josephine to decline Kahlil’s proposal of marriage. It was this concern and love for Josephine that motivated Kahlil to write “The Prophet”. The title of the book was based on a lengthy poem that she had written in December 1902, describing Kahlil’s life in Bsharri, as she had visualised it. When the book was published, Kahlil dedicated the same to her.

The miseries in Kahlil’s family kept on escalating, and in February 1903, his mother underwent a surgery to remove a cancerous tumour. To add to this emotional burden, Kahlil was compelled to take care of the family business and manage the goods store that Peter had left behind in order to seek a fortune in Cuba. The added responsibility deprived the 20-year old Kahlil of the time required to pursue his artistic interests. So disturbed was he with the atmosphere of poverty, illness and death that he avoided being at home. In March, the same year, Peter returned to Boston gravely sick due to tuberculosis, and on March 12, he breathed his last. His mother’s cancer too was spreading rapidly, and she too succumbed to her illness on June 28, 1903. After her death, Kahlil’s sister Marianna worked as a seamstress to make a living for them.

Beginning of a Literary Career

Three deaths in a row left Kahlil devastated. He sold off his family business and engaged himself in enhancing his writing skills in Arabic and English. On the other hand, Fred and Josephine helped him launch his debut art exhibition. It featured his transcendental metaphysical vision in the form of allegorical and symbolic charcoal drawings that enticed the society of Boston. The exhibition commenced on May 3, 1904, and resulted in an instant success with the critics. Some of his works were also sold.

What also made the exhibition special was the admittance of another woman in Kahlil’s life. Josephine had invited Mary Elizabeth Haskell to examine Kahlil’s works. Mary who was ten years elder to Kahlil was the owner of “Miss Haskell’s School for Girls”, and later the headmistress of “The Cambridge School”. She later made Kahlil one of her protégés. As opposed to Josephine’s romantic nature, Mary was a headstrong and independent lady who was also an active champion of women’s liberation. This meeting marked the onset of a lifetime relation that significantly influenced Kahlil’s writing career. As far as his frequent liaisons with older women were concerned, it could be presumed that he was seeking a mature woman, perhaps someone like his mother. This might be due to his emotional insecurities that prompted him to find a loving mother like figure who could quench his emotional and spiritual needs, rather than his physical desires.

Mary offered financial aid for Kahlil’s artistic development and motivated him to be the artist he had always dreamt to be. Later on, she paid for him to attend an art school in Paris and fulfil his aspiration of becoming a symbolist painter. She convinced him to refrain from translating his Arabic work and rather concentrate on writing in English directly. It was as per her advice that he decided to explore writing in English. Her partnership and editing refined his work and made it an impeccable piece. She spent hours with him in the process, making correction wherever needed and recommending new ideas to his writings. She also took the effort to learn Arabic to apprehend his language and thoughts better.

Books and Publication

The year 1904 witnessed 21-year old Kahlil’s first published written work, with his contribution of articles to “Al-Muhajir (The Emigrant)”, the Arabic émigré newspaper. His first publication ‘Vision’ was a romantic essay that described a caged bird amidst plenty of symbolism. Back in Bsharri, to master Arabic language and traditional vocabulary, Kahlil had relied mostly on the Arabic stories narrated there and therefore his writings had a colloquial touch to them. As per his views, the conventional rules of language were meant to be broken. He advised the Arab émigré writers to break out of the monotonous tradition and seek an individual style.

Kahlil’s writings were charged with passionate intensity and lyrical fervour. Though they were meant to enlighten the Lebanese and urge them to rise from their sleep and slavery, yet, they had a universal appeal, significance and validity. Kahlil was a visionary who implored for the reformation of society on a moral basis. However, all his life, his Arabic writings got no critical praise as his English books, which later led him to focus on his English writings, rather than improving his Arabic style.

Kahlil earned his living in Boston through his sketches, poems, and prose-poems. He contributed articles to other Arabic newspapers like “Mir’at al-Gharb (the Mirror of the West)”. In 1905, 22-year old Kahlil’s first Arabic book “Nubthah fi Fan Al-Musiqa (On Music, a Pamphlet)” was published. It praised music and was inspired by Peter’s ‘oud’ playing and several visits to the opera with Fred. The same year, Kahlil began a column in “Al-Mohajer (The Immigrant)”, a leading Arabic newspaper in New York. The column was called “Tears and Laughter”, fragments of which formed the basis of his book “A Tear and a Smile”. During his tenure with “Al-Mohajer”, Ameen Rihani, an Arabic émigré writer wrote to the magazine praising Kahlil’s article that attacked the modern Arab writers for copying traditional writers and using poetry for financial gain. He later became a significant Arabic writer and Kahlil’s friend. However, later on, Kahlil left Rihani for the life-long companionship of Mikhail Naimy, a Lebanese author and poet of “The New York Pen League”.

Kahlil’s writings started portraying a rebellious spirit against human domination and injustice. “Ara’is al-Muruj”, published in1906 was translated as “Brides of the Meadows” or “Spirit Brides”, but Kahlil referred to it as “Nymphs of the Valley”. The book was a collection of three allegories that take place in Northern Lebanon and expressed the young writer’s anti-feudal and anti-clerical convictions. The allegories – “Martha”, “Yuhanna the Mad”, and “Dust of Ages and the Eternal Fire”, dealt with issues relating to prostitution, religious harassment, rebirth and destined love. The allegories were largely influenced by the stories Kahlil had heard in Bsharri and his own fascination with the Bible and the mystic nature of love. Kahlil spoke on the subject of insanity in his English book “The Madman”, the early stages of which could be traced to Kahlil’s initial Arabic writings. Kahlil’s early Arabic publications were categorized with the use of the ironic, the practicality of the stories, the depiction of mediocre citizens and the anti-religious quality which was contrary to the formalistic and traditional Arabic writings.

His book, “Al-Arwah al-Mutamarridah (Spirits Rebellious)”, a collection of four short stories published in 1908 was burnt in public in Beirut and censored by the Syrian government, because of its revolutionary ideas. For example, an excerpt from the book said, – “Let us disperse from our aloofness and serve the weak who made us strong, and cleanse the country in which we live. Let us teach this miserable nation to smile and rejoice with heaven's bounty and glory of life and freedom.” The book dealt with social problems in Lebanon, picturing a married woman’s liberation from her husband, a heretic’s plea for liberty, a bride’s escape from an unwanted marriage through death and the violent injustices of the feudal lords in 19th century Lebanon. It criticized the authority exhibited by, both the Church and the State. Kahlil was condemned by the village authority for comparing the monks’ wealth with the poor peasants, and for encouraging the latter to snub the authority’s rule over their lives. Later in his life, when he was distressed with death, illness and lost love, Kahlil mentioned to Mary about the dark period in which this book was written.

Journey to Paris and Shifting to New York

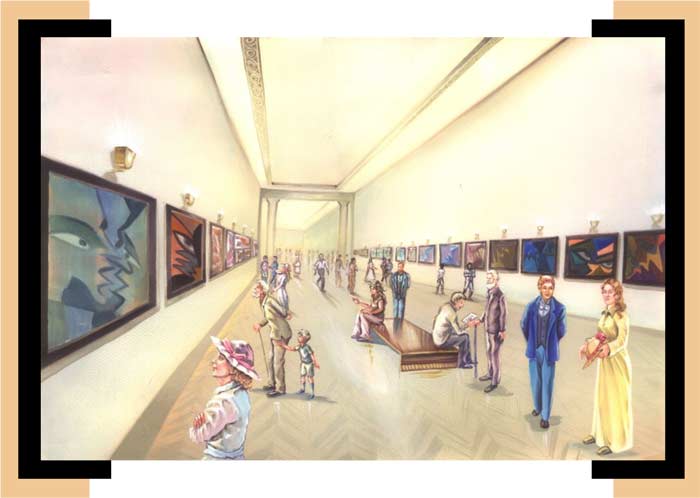

With Mary Haskell funding his studies, Kahlil, now 25 years old, set off to Paris on July 1, 1908, to learn art for two years. He enrolled himself at “Académie Julian”, an art school that prepared students for the exams at the prestigious “École des Beaux-Arts”. He learnt art under the guidance and supervision of August Rodin, the famous French sculptor. In Paris, Kahlil was in awe of the French cultural environment and spent his time analysing paintings at various museums and exhibitions. Previously, he had refrained from taking formal coaching as he was confident about his own capacity, but now he realised his lack of artistic training and felt critical of his sketches. He felt estranged with the academy and hence, left it, to practice an unrestrictive self-exploration of his art.

Kahlil along with Joseph Hawaiik (his classmate in Lebanon with whom he had started al-Manarah), sketched models and visited exhibitions. In Paris during 1910, Kahlil met his old acquaintance Ameen Rihani, who was on his way to New York. Kahlil admired him for his sardonic humour and writing style. Both shared Lebanon memories, Maronite background and their association with the social issues of that period. They roamed around London for a couple of weeks to familiarise themselves with the city’s art life and then parted ways. Kahlil came back to Paris and Rihani went on his way to America. In due time Kahlil returned to Boston.

Return To Boston

On October 31, 1910, Kahlil returned to Boston once again, ending his travel abroad. He planned to settle down and focus on his writing. He discussed with Mary his plans to shift to New York for greater artistic opportunities there.

In December, the same year, Mary began to pen down a daily journal dedicated to her memories of Kahlil’s life. Her series of diaries, ranging to seventeen and a half years, forms one of the best and the most complete records of Kahlil’s life and work. In it, she recorded his artistic growth, their personal and intellectual conversations and his innermost thoughts. This provided the critics an access into his personal thoughts and ideas that he had otherwise kept away from others.

On December 10, 1910, Kahlil proposed Mary to marry him but unfortunately, she denied. Her refusal was due to the age difference between them as she was ten years older to him. However, their relation continued; a relation that began as mere associates and developed to a romantic affair and further to an artistic alliance. Another factor that stood between them was money. With Mary funding Kahlil, he felt that it could overshadow their spiritual attachment. The feeling of continually being indebted to her financially bothered him and hence they frequently fought over the issue. However, Mary never felt superior to Kahlil for funding him, as it wasn’t Kahlil alone that she had offered financial help. She had provided funds to other immigrants as well whom she found to be promising students. However, none of them became as famous as Kahlil.

In seek of Artistic Growth in New York

In 1911, the 28-year old Kahlil drew a portrait of the famous poet “WB Yeats”. It was one among a string of portraits that Kahlil later named the “Temple of Art” series.

In this he had more portraits to his credit like “Debussy (classical composer)”, “Rostand”, “Auguste Rodin( French sculptor)”, “Sarah Bernhardt( French film actress)”, “Charles Russell”, “Henri Rochefort( a critic)”, “Carl G Jung( a Swiss psychologist and psychiatrist)” and “Abdu’l-Baha( the leader of Bahai faith)”. Kahlil also occupied himself in political activity as he joined the “Golden Links Society”, a group of young male Syrian immigrants who worked to improve the standard of living of Syrians everywhere. The same year, Italy declared war on Turkey and the Syrian liberals dreamt of a free home rule in the Ottoman dominated countries. Kahlil’s hope to overthrow the Ottoman rule was also fuelled when he met the Italian General “Giuseppe Garibaldi”, the grandson of the Grand Italian General. Later, during the World War I era, Kahlil became a great advocator and leader of the unified Arabic military action against the Ottoman rule.

In the meantime, Kahlil continued his association with the Arabic newspapers like “Mir’at al-Gharb (the Mirror of the West)”, and contributed articles till 1912. On April 12, 1912, encouraged by Mary’s reference letters that assured to raise his contacts, he moved to New York for a better artistic life. For a while, he stayed with the Rihanis and then later, rented a small studio at “51 West 10th Street Studio for Artists” in Greenwich Village. Here he dedicated his time to painting and writing literary essays and short stories, both in Arabic and in English. Kahlil familiarised himself with the art and life of the city and drew portraits of eminent personalities for income. He also completed his first book of illustrations and a cover picture for Rihani’s Book on Khalid. The same year, Kahlil received news about his father’s death.

In 1912, one of Kahlil’s famous works in Arabic was published – “Al-Ajniha Al-Mutakassirah (The Broken Wings)”. Though it was dedicated to Mary, the experiences mentioned were not related to them. It was a poetic novel and a tragic tale of love, doomed by the restrictions of a cruel society, set in Beirut. It was the story of a young man, who falls in love with a young woman named Selma Karamy. She gets engaged to a prominent religious man’s nephew and they began to meet in secret, only to be caught one day. Thereafter, Selma is forbidden to leave her house. She later dies at childbirth. In the novel, Kahlil described the plight of women as ‘the bird with broken wings in a cage’.

The book covered a lot of topics like power of love, prayer, sacrifice, social issues of the time in the Eastern Mediterranean, like miserable condition of women, male chauvinism, religious corruption and hypocrisy. The story was related to Kahlil’s brief affair during his education in Lebanon, with 22 year old Sultana Tabit, a widow of that native village. He is said to have narrated to Mary his story with Sultana with whom he had exchanged love poems and books.

But sadly, she died, leaving Kahlil with her memories in form of jewellery and clothes. Some critics related the novel to his failed love affair with Hala Dahir, a Lebanese teenager two years elder to him and the eldest daughter of his childhood mentor Selim Dahir. Another reference was said to be ‘The Wings’, a one-act play written by Josephine in 1904, during her courting days with Kahlil.

In 1913, the 30-year old Kahlil joined the panel of “Al-Funun”, the newly founded Arab emigrant magazine. This journal, published by the Arab community of New York, was committed to the development of literary and artistic issues. The magazine’s expression of Kahlil’s open-minded approach to style enabled him to contribute many articles, which later formed the basis of his first English book, “The Madman”. He also contributed articles to another émigré magazine called “Al-Sa'ih (The Traveller)”.

Kahlil began writing “al-Majnun (The Madman)” in 1913. Narrated by the titular madman, this book was a collection of parables and poems. The concept of the novel had captivated his interest right from the time he learnt of how the mad were treated in Lebanon. He came to know that the mad were considered to be possessed by the spirit of the Jinn (the devil), and were exorcised by the Church to take the devil out. An excerpt from the English version of the book is as follows, “For the first time the sun kissed my own naked face and my soul was inflamed with love for the sun, and I wanted my masks no more. And as if in a trance I cried, ‘Blessed, blessed are the thieves who stole my masks’. Thus I became a madman.”

During this period, Kahlil took a liking for Nietzsche’s style and his ‘Will-to-Power’ concept that was actually in contrast to Kahlil’s interpretation of Christ. Nietzsche, a German philosopher, felt that Christianity and the social institutions were responsible for the dehumanization of people and occurrence of ‘slave morality’. He portrayed Christ as being a weak person, but to Kahlil, Christ was an admirable mortal to whom he dedicated his longest work in English, “Jesus, The Son of Man” in 1928.

In the meantime, Mary and Kahlil worked on editing and revising “The Madman”. In 1914, the 31-year old Kahlil’s fifth Arabic book, “Kitab Dam’ah wa Ibtisamah (A Tear and A Smile)” got published, which was an anthology of his earlier writings in the “Al-Muhajir” newspaper.

World War I, Publication of ‘The Prophet’ and other works

With the beginning of World War I, Kahlil got actively involved in politics. He asserted the unity of the Muslim and Christian forces to bring down the cruel Ottoman power. So obsessed was he with the thought of leading his country to freedom, that he discussed with Mary his desire to move to Lebanon to become a fighter. Mary however refused blatantly. In 1914, Albert Pinkam Ryder, an American architect, paid an unexpected visit to Kahlil’s art exhibition. He left a deep impression in Kahlil’s mind, who in turn wrote an English poem in the former’s honour. This was Kahlil’s first English publication and went to print in January 1915.

In 1915, Kahlil had to undergo an electric treatment for the pain in his left shoulder that was beginning all over again. This was due to a critical bruise he had obtained when he had fell off a cliff, during his childhood days in Lebanon. Apart from the pain, during the war years, Kahlil also went into a depression that distracted his mind and further weakened his health. Though Kahlil aggressively wrote, supporting the Arab revolting the Ottoman rule, he felt helpless and donated his savings to the starving Syria.

To relieve his mind of all the war thoughts disturbing him, Kahlil joined the literary magazine called “The Seven Arts” in 1916. He was the first immigrant to join this magazine panel and was in demand in the literary circles; many wanted to hear recitations from his writings. In 1918, he told Mary about the work he had been keenly involved in. He called it “My Island Man”. This was also the beginning of his most distinguished book, “The Prophet”. In Mary’s diary she had mentioned Kahlil’s thoughts about the book where he addressed it as ‘the first book in my career – my first real book, my ripened fruit’. Mary played a vital role in the development of this work, as it was she who advised him to write this book in English. In 1919, Kahlil came up with the title, ‘The Prophets’ for the work, but Mary was against it and preferred using the title ‘The Counsels’, a name which she used even after the book was published.

Kahlil’s first English book “The Madman” was published in 1918 by the American firm of Alfred A Knopf, and received good feedback. It was a collection of life-affirming parables and poems, throwing an ironic light on the beliefs, aspirations and vanities of humanity. The book was illustrated by three of Kahlil’s drawings. The success of this book escalated his popularity to the extent that he became too busy with his work and lost touch with his old friends like Fred and Josephine. It also strained his relation with Rihani. In 1919, ‘Twenty Drawings’, a selected collection of his drawings with an introduction by Alice Raphael, was published in New York.

Kahlil expressed to Mary his wish to write small unified books that could be carried in one’s pocket and read in one go. In the period between 1918 and 1926, he wrote four such books, and these were his first in English: “The Madman (1918)”, “The Forerunner (1920)”, “Sand and Foam (1926)” and “The Prophet (1923)”. “The Forerunner” and “Sand and Foam” were a collection of parables and aphorisms which in true Eastern style drew on a world of kings, hermits, saints, slaves, deserts and animals that talked and wind that laughed.

Kahlil’s poem “Al-Mawakib (The Processions)”, which was his first traditional Arabic poem with proper rhyme and meter, was published in 1919. It was a long poem in the form of a dialogue between two voices, one that of a spiritually liberated man and the other of a man in bondage. However, it received little success from the Arab press. Though all his life, Kahlil joined several societies and magazines which motivated the avant-garde Arabic writing and united the Arabic literature abroad, he however, did not excel much as a successful Arabic writer. His writing in the language was still not up to the standards and achieved little success in the Arabic Press. However, more Arabic works followed like “al-'Auasij (The Tempests)” in 1920, which was a collection of poems and essays characterised by the underlying theme, ‘revolt against man the self-enslaved in the name of man the self- emancipated’ and “al-Bada'i' waal-Tara'if (The New and the Marvellous)” in 1923, which was a collection of numerous narratives and essays.

In 1919, the 36-year old Kahlil went on board of another local magazine “Fatat Boston”, to which he contributed several Arabic articles. Here he formed a close relationship with “Mikha'il Na'ima”, whom he had met years ago. Naimy, a critical thinker then, was one of the first Arab writers to acknowledge Kahlil’s efforts at enhancing Arabic and accurately making use of the Arab customs and background.

In 1920, Kahlil, along with Naimy, joined a ten member Arab émigré organisation called “Al-Rābiṭah al-Qalamiyah”, a movement for the rebirth of Arabic literature. It was also spelt as “al-Qalamiyya” and called “The Pen League” in English. This organisation also known as “al-Mahjar (emigrant)” was the first Arab-American literary society, formed originally by “Nasib Arida” and “Abdul Massih Haddad” in 1915-1916 and later re-formed in 1920 by the group led by Kahlil. Through this movement, Kahlil demanded greater artistic freedom, encouraging writers to break the rules, search for individual styles and promote a new generation of Arab writers. The ten members that formed the group were “Kahlil Gibran (President)”, “Mikhail Naimy (Secretary)”, “Nasib Arida”, “Raschid Ayoub”, “Wadi Bahout”, “William Catzeflis”, “Abdul Massih Haddad”, “Nudra Haddad”, “Elia Abu Madi” and “Ameen Rihani”.

Kahlil managed to complete three-quarters of ‘The Prophet’ by 1920. In 1922, at the age of 39, he complained about heart trouble which was a result of his nervous psychological state. This was due to his mental conflict that resulted from the frustrated mind of an artist who knew his creative potential, believed he could prove his ability, but could not justify the same.

In fact, he once admitted, “But my greatest pain is not physical. There’s something big in me... I’ve always known it and I can’t get it out. It’s a silent greater self, sitting, watching a smaller somebody in me do all sorts of things.”

Meanwhile, ‘The Prophet’ neared completion and Mary helped him in all possible ways. She advised him about the style, covering issues like use of capitalisation, punctuation marks and the form of paragraphs. A couple of months before the publication of the book, Kahlil summarised it to Mary – “The whole Prophet is saying one thing: ‘You are far far greater than you know – and all is well.” The book finally came to print in October 1923.

By 1923, 40-year old Kahlil had become a reputed figure in the Arab world through his writings. And now that his confidence in English writings developed, he became less dependent on Mary as a sponsor and editor. Over their regular quarrels over money it was agreed that he would send her several of his paintings to pay off his loans. Though he relied lesser on her opinions related to writings, her face remained a constant source of inspiration for his illustrations.

The Final Years

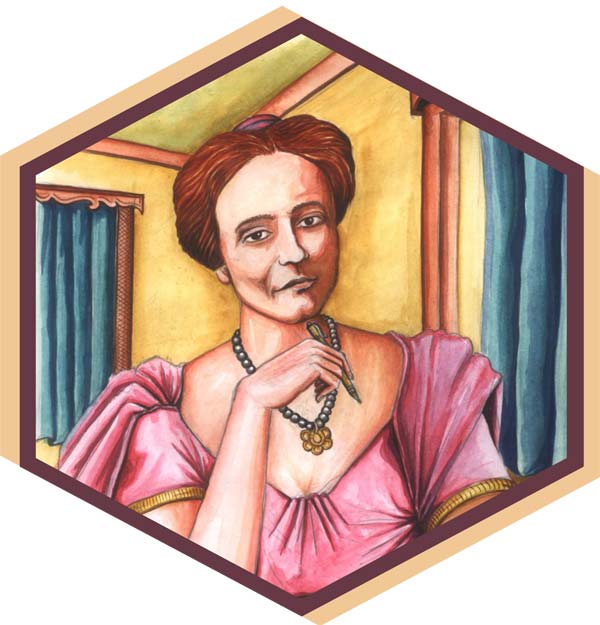

By 1923, a new figure stepped into Kahlil’s life. He had developed a close communication with “May Ziadeh”, an Arab writer.

She was an intellectual writer and an active supporter of women’s liberation. In 1912, she had written to Kahlil telling him how she was moved with the story of Selma in “The Broken Wings”. She was fluent in English, French and Arabic and had published her poems under the pseudonym “Isis Copia” in the year 1911. Years later, she even managed to replace Mary’s role as an editor and conversant. Though they never met in person, they continued their correspondence till the end of Kahlil’s life. The exchange of letters that initially contained views and opinions pertaining to literature, gradually extended to a more spiritual and passionate level. The articles she wrote on Kahlil were widely read in the Arab world, which not only made him famous but also established her as a critic.

This period saw Kahlil’s active participation in the political field and writing in depth about the society’s cultural issues. He recommended the emerging Arab countries to adopt positive aspects of the Western culture. Back in his native country, his writings became controversial with its views about the Church and the clergy. Hence, he focussed more on his English writings rather than trying further to gain acceptance as an Arabic writer.

Although by now Mary had a very limited role in Kahlil’s writing career, yet she was always with him when needed; be it for emotional assistance or to handle his financial issues due to a failed real estate deal. He also discussed with her his plans about writing the second and third parts of “The Prophet”, thus making it a trilogy. The first book was set on the eve of the Prophet’s departure from Orphalese to his native island. He wanted to name the second part “The Garden of the Prophet” as it was based on humanity’s relationship with Nature and would narrate the period which the Prophet spent in the garden of his mother on the island, talking to his followers. The third part would be named “The Death of the Prophet” as it spoke about humanity’s relationship with God, and described the Prophet’s return from the island, his imprisonment and being stoned to death in the marketplace after being freed. However, due to his failing health and being engaged in writing his longest English book, “Jesus, The Son of Man”, Kahlil’s desire to write the second and third part of “The Prophet” was never completed.

Kahlil appointed Henrietta Breckenridge Boughton as his new secretary to assist him in his editing work and manage his studio. She was with him for the last seven years of his life. By now, the 43 old Kahlil was a renowned international figure and was contributing articles to the quarterly journal “The New Orient”, which had an international approach encouraging the East and West to meet. He had also started working on his new English work “Lazarus and His Beloved”, a one-act play that was based on an earlier Arabic work. Kahlil still relied on Mary (who was now married to Jacob Florence Minis, a southern land owner and merchant) for editing his work before it went for printing. Writing a story about Jesus and portraying Him in a way no one had, was Kahlil’s lifetime ambition. In November 1928, the book was published and received excellent reviews from the local press.

By 1929, every possible society wanted to give the 46-year old Kahlil a tribute. In honour of his literary success, a special anthology of Kahlil’s early works was issued by “Arrabitah” under the title “As-Sanabil”. By this time, Kahlil had turned alcoholic as he found relief in it from his unbearable body pain. He started planning about post-life and made enquires about buying a monastery in Bsharri, which was owned by the Christian Carmelites. In 1919, doctors traced his ailment to the enlargement of his liver. To distract himself from the seriousness of his condition, Kahlil ignored his medication and further relied on alcohol. He also diverted his attention on an old work written in 1911, about three Earth Gods. “The Earth Gods”, a long prose poem, narrated the story of three Earth Gods who watch the drama of a couple falling in love. Mary edited the book and it went into print in mid-March 1930. Kahlil’s drinking habits further aggravated his condition and he soon made the last copy of his will. He told Mary about his desire to build a library in his native village Bsharri. He admitted to his pen-friend, May Ziadeh, his fear of death. He wrote to her, “I am, May, a small volcano whose opening has been closed.”

The undetected cancer in Kahlil’s liver left him unconscious and he breathed his last on April 10, 1931 at the St. Vincent Hospital, New York. With him passed away into eternity, the romanticisms of an entire era, the lyrical magic in literature and the “prophet” who enlightened the darkest corners of the human mind with his superior thought and innate humaneness. Both, the US and Lebanon, mourned for this 48 year old genius. As per his will, he left a huge sum of money for his country Syria as he wanted its citizens to remain there and develop it, rather than immigrate. Regardless of the ups and downs that Kahlil and Mary’s relation went through, he must have had immense trust and gratitude for her to have put a part of his will in her name. Mary received all the contents of his studio, and among other numerous things, she found her own letters written to him. Though she thought of burning them earlier, she later handed them to the University of North Carolina, considering their historical importance. In 1972, excerpts of over six hundred letters were published by the name “Beloved Prophet”. Mary, Mariana and Henrietta managed Kahlil’s studio, organised his works and sorted his books, illustrations and drawings. Henrietta also played another important role following his death. Kahlil had only partially written “The Garden of the Prophet”, and it was she, who under the pseudonym “Barbara Young” completed and published it posthumously in 1933. However, to what extent the book is actually Kahlil’s authentic work, is controversial.

In July 1931, as per Kahlil’s wishes, Marianna and Mary went to Lebanon to bury him in his hometown of Bsharri. Rather than mourning, a grand procession greeted his body, and the citizens of Lebanon rejoiced his homecoming. His death had made him more popular. The Lebanese Minister of Arts opened the coffin and honoured his body with a decoration of Fine Arts. By January 1932, Mariana and Mary bought the Mar Sarkis monastery and Kahlil moved to his final resting-place in the shadow of a boulder, very close to the Holy Valley. Mary donated over a hundred original works of art by Kahlil to “Telfair Museum of Art” in Georgia from her own personal collection. It is the largest public collection of his visual art in the country. Later, upon Mary’s proposal, Kahlil’s belongings, the books he read and some of his works and illustrations were shipped to provide a local collection in the monastery that was converted into a Kahlil museum.

Kahlil’s pen pal cum soul mate, May Ziadeh, who like him was unmarried, fell into depression after the death of her parents and Kahlil. She was admitted to a mental asylum by her uncle, where she had to endure harsh and inhuman treatment. She was finally released by the help of her writer friends like Ameen Rihani, but passed away in 1941 at the age of 55.

The Arabic world eulogized Kahlil Gibran after his death as a genius and patriot. Arabic scholars praised him for pioneering Western romanticism and a free style approach to strict Arabic poetry. The words imbibed on Kahlil’s grave read, “I am alive like you, and I am standing beside you. Close your eyes and look around, you will see me in front of you ...” Truly, Kahlil Gibran, in his life and through his work has showed that “though the month of April might vanish... Gifts of joy do not depart.”

Biography of Khalil Gibran | 3 Comments >>

3 --Comments

Thank you for the good writeup.

Wow actually a great post. I like this.I just passed this onto a colleague who was doing a little research on that. And he actually bought me lunch because I found it for him. Overall, Lots of great information and inspiration, both of which we all need!

Leave Comment.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked.

Thank you for share very good knowledges. Your web is very good I am impressed by the information that you have .Bookmarked this page, I found just the information I already searched everywhere and just couldn’t find. What a perfect site. I like this data presented, so keep up the good work!