Tags : Composer, Pianist, Western Art Music, Romantic Era, Classical Era, Symphony, Quartets, Sonatas

- Text Size +

INTRODUCTION

♫

A friend in joy,

A friend in sorrow;

Music can delight,

Music can heal;

For Music is love.

♫

The lyrics of music,

Like enchanting nature;

Enthralls the world.

For Music is life;

The rhythm of the soul,

The very strand of life.

♫

How would life be without music?

A landscape without the sun,

A soundscape without any sound,

A mindscape without any magic,

A soul without a heartbeat.

Can anyone do without music? Not me definitely. The beauty of music is actually inexplicable. It is a free art form enveloping us in its soundscape, bringing transformation and growth by healing us, loving us, and uniting all of humanity due to its interconnectedness.

Man has absorbed the sounds in nature to form the language of music. Music was also a precursor to the spoken language; it was instrumental in shaping it. Earlier, the sounds in nature were mimicked for interpersonal communication. Later as man evolved over the ages, his brain too underwent changes and language was formed. These natural beautiful soundscapes; the original music were adapted to serve modern auditory soundscapes.

Listening to good music lifts our dismal spirits, calms our frayed nerves, energizes and motivates us to achieve our goals. It is the soothing balm of life; a respite for the weary; a retreat for the soul. Music transports us into a different world where we can glow in the warmth of sunshine, dance in the beautiful rain, walk through lush green meadows and even stay in a sweet little cottage with the backdrop of the mountains. It is the external manifestation of our internal feelings; the language of our hearts unhindered by any barriers of language or region.

Many music composers have rendered beautiful music and have left a deep impact in the world. Their music is a wonderful legacy for the future generations. One such great music composer whose compositions have touched a chord in our hearts and made our lives magical was Beethoven. According to him,

“Music is the wine which inspires one to new generative processes, and I am Bacchus who presses out this glorious wine for mankind and makes them spiritually drunken.”

German composer and pianist, Ludwig Van Beethoven is considered as one of the giants of classical music; which is a well-established music in the West. Western Classical music has many forms; right from a solo to huge symphonic orchestras; from a sonata to an opera. Beethoven’s musical influence had a pivotal role in the transition from 18th century Classicism to 19th century Romanticism in Western art music. He is one of the most famous and influential of all composers, who made a profound impact on the subsequent generations of composers. The arrays of his compositions include Symphonies, Concertos, Sonatas and String Quartets. Besides these, he also composed chamber music, vocal, choral works and even an opera. He was an innovative genius who widened the scope of his work by a combination of vocals and instruments.

At the pinnacle of his fame, Ludwig Van Beethoven was recognized by the mightiest in the land, the Kings and Emperors, as the greatest among the greatest of all composers. It is said that, “If Bach is the mathematician of music, Beethoven is its philosopher.”

Beethoven’s musical compositions have an enormous reach and influence. To him, art had no limits and he created more than just a new musical style. His love and total belief in his music modified the century in which he lived and nothing was ever the same again after him.

Beethoven is sometimes referred to as one of the “three Bs” (the other two being Bach and Brahms) of the greatest composers in music history. Now let us compose ourselves and journey onwards to the beats of Beethoven’s life right from the note of his birth.

♪ ♫ INTO THE MUSIC BORN ♪ ♫

Beethoven’s family originated from the province of Flemish Brabant in Belgium. His father and grandfather were both court musicians. Beethoven’s grandfather was Lodewijk van Beethoven (b.1712), a musician from Mechelen, Belgium who moved to Bonn at the age of 20. Grandfather Lodewijk (Dutch for the German Ludwig) worked as a bass singer at the Elector of Cologne’s Court, and rose to become Kapellmeister (music director) eventually. He was a very prosperous and eminent musician in Bonn. He had one son, Johann (b.1740), who was also a Court Tenor singer and pianist. Music thus ran in the family. Johann Beethoven married Maria Magdalena Keverich (b.1746), on 12th November, 1767, in the Catholic St. Remigius Church in Bonn. Maria was the daughter of Johann Heinrich Keverich, head chef at the Court of the Archbishop of Trier. Johann and Maria gave birth to seven children – five sons and two daughters. Of these seven children, four unfortunately died before reaching adulthood and only three boys survived. Ludwig was their second child and the eldest among the surviving three.

Ludwig Van Beethoven was baptized on 17th December, 1770, as per the registry at the Parish of St. Remigius in the city of Bonn, in the Electorate of Cologne, in Germany. Hence, his date of birth is said to be the 16th of December since it was customary for baptism to be done a day after birth. Bonn was then the capital of the Electorate of Cologne and a part of the Holy Roman Empire.

Ludwig’s father and mother were by nature diametrically opposite. His father, Johann, besides being rude and demanding, was a hard-drinker, while his mother Maria was sweet, gentle, and deeply moralistic. The situation at home affected Ludwig deeply. He did not have a happy childhood for though he adored his mother, he feared his father very much.

Ludwig’s grandfather gave him a lot of affection. Well, that is some compensation for the lack of affection from his father! He took him walking through the fields and valleys, talking about the different lively animals and the blooming fragrant flowers. One day, Ludwig’s grandfather made him sit on his lap. Being a musician himself, he was eager to make his little grandchild hear the names of renowned music composers. Ludwig’s grandfather told him, “Han-del”, “Ba-ch” and “Mo-zart” and smiled, looking at the innocent bewilderment on his face. Like every other grandparent who wishes the best for his grandchild, perhaps he wanted Ludwig to become a great musician like them! However, this beautiful association could not last forever, for in the year 1773, Ludwig’s grandfather passed away in his sleep.

Ludwig’s father worked in the Elector of Cologne’s Chapel. He dealt with his household and its members with an iron hand since they had to subsist on his paltry income of £ 30 per annum. In his spare time, he taught music and even though he did not have any great musical talent, the children of the nobility came to him for music lessons.

One day little Ludwig was turning the iron handle of the window shutters; the sound that it made attracted him and he began playing with it repeatedly. This was just the beginning of his musical affinity and he soon became absorbed in music.

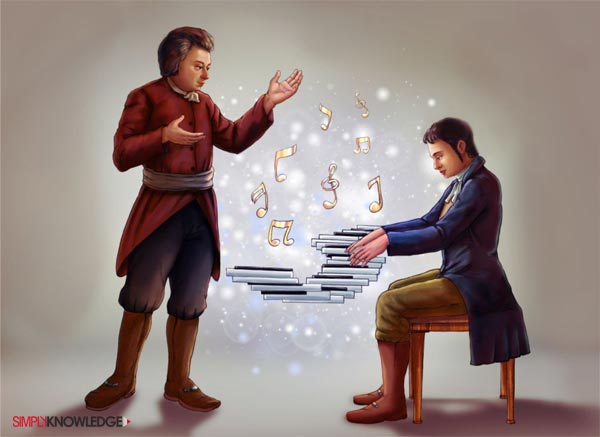

About this time, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was being hailed as a ‘musical wonder’. But Johann Beethoven was inspired by the accomplishment of Leopold Mozart, the father of Wolfgang. Johann noted that Ludwig had the musical ability, hence he began to tutor him. Thus at the age of 4, Ludwig started to learn music from his father.

His father gave him music practice and exercises regularly. Ludwig learned everything – piano, violin and harmony lessons – quietly and readily, under his strict training. His father nurtured his talent, even seeing it as a source of income and envisioned creating another child prodigy, like Mozart.

The birth of Ludwig’s younger brothers, Caspar Anton Carl on 8th April, 1774, and Nikolaus Johann on 2nd October, 1776, added to Ludwig’s delight. Ludwig went to elementary school at 1091 Neugasse (Bonn). Later he went to Münsterschule and finally, Tirocinium, a Latin grade school. He was just an average student and a classmate of his once remarked, “Not a sign was to be discovered of that spark of genius which glowed so brilliantly in him afterwards.”

On 26th March, 1778, Ludwig Van Beethoven gave his first public performance at Cologne. This was at the age of 7, though his father had announced his age as six, for he wanted his son to be recognized as a child prodigy like Mozart. Though Beethoven gave an impressive recital, there was no press coverage.

By the age of 9, he had finished learning all that he had to learn from his father’s limited musical knowledge and teaching abilities. In order to groom his talent further, his father later put the young Beethoven under the charge of other local teachers. So Beethoven came under the notice of tenor singer Tobias Friedrich Pfeiffer and another local teacher Zambona. Pfeiffer who was a boon companion of his father’s, taught him the piano, while Zambona gave him general education with lessons in Latin, French and Italian. Court organist Gilles van den Eeden taught him to play the keyboard and Ludwig’s cousin Franz Rovantini taught him the violin and the viola.

♫ ♫ ♫ MUSICAL NOTES ♫ ♫ ♫

In 1779, renowned musician Christian Gottlob Neefe was appointed the Court’s Organist. At the age of 10 years, in 1781, Beethoven stopped attending school and began pursuing his music studies full time under Neefe. Neefe became his most important teacher in Bonn. He gave him instructions in organ playing, musical theory and composition and also introduced him to the works of ancient as well as modern philosophers. It was through him that Beethoven was initiated to the music of the famous German composer, Johann Sebastian Bach.

The knowledge thus gained showed a marked improvement in Beethoven’s artistic ability, making his compositional talent soar up. On a short musical tour to Holland, Beethoven even earned some money. At the age of 11 years, he worked as Neefe’s deputy organist in the Elector’s Chapel at Bonn.

By 1782, he was playing his compositions very well and in that year, his first composition, “9 Variations in C Minor for piano”, a set of keyboard variations (Wo0 63) on a march theme by Earnst Christoph Dressler, an obscure classical composer, was published. Writing about his pupil Beethoven in the “Magazine of Music” in 1783, Neefe even prophesized proudly, “If he continues like this, he will be, without a doubt, the new Mozart.” In 1783, Beethoven was appointed as the accompanist or deputy conductor of the Opera band.

However, by this time, Beethoven had caught the eye of the Bonn folks. His first three piano sonatas, named “Kurfürst” (“Elector”), which was dedicated to the Elector Maximilian Frederick, were published in 1783. Elector Maximilian Frederick had noticed Beethoven’s talent early and encouraged his musical studies. In June 1784, he appointed Beethoven as second Court Organist, upon the recommendations of Neefe. From this year, Beethoven worked as a paid employee of the court chapel conducted by Kapellmeister (music director) Andrea Luchesi.

Elector Max Frederick passed away in 1784. His successor, Maximilian Franz, became the Elector of Cologne. Franz was the youngest son of Empress Maria Theresa of Austria and brother of Emperor Joseph II of Vienna. At that time, Elector Max Franz had even wondered whether to dismiss Neefe and appoint Beethoven instead as chief organist. Soon, the Elector formed a national opera after remodelling his band, and Beethoven played the viola in this opera. Anton Reicha (flutist), Franz Ries and Andreas Romberg (both violinists) were also members of this band. Beethoven was then 14 years old and his social circle changed. The widening of his social circle got him some friends for life - the Ries family, the Von Breunings, the charming Elenore, violinist Karl Amenda and Doctor Franz Gerhard Wegeler, who became a very dear friend.

Elector Franz increased his support for education and the arts. He continued with the reforms initiated by his predecessor, which was similar to his brother Joseph II’s reforms in Vienna, based on Enlightenment philosophy (the productive movement in which liberal reforms were imposed from above.) Neefe and others, including Beethoven were members of the local chapter of the Order of the Illuminati (1781-85), which was founded with the aim of improving man’s moral character, and support and promote knowledge independent of the Church – ideas closely related to freemasonry. Beethoven was most certainly influenced by the philosophical, religious and political changes in this period.

♪ ♫ ENCHANTING VIENNA ♪ ♫

In the year 1787, the tutelage over, Beethoven and Neefe parted ways. Beethoven was just 17 years old then. In later years, Beethoven discounted both - the association and the instruction. The musical capital of the world, Vienna, beckoned Beethoven. Europe’s cultural capital was to become his home. Beethoven wished to meet Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in Vienna and further his musical education. Beethoven’s patron, Elector Max Franz provided the necessary funds for the journey to facilitate his study.

A formal meeting of these sons of art took place. Beethoven played to an extempore theme so effectively that Mozart is said to have told his friends, “Pay attention to him, he will make a noise in the world some day.”

Yes, a lot of noise Beethoven did make later, but of the type that one would want to rewind and play again and again. The great unknown from Bonn had made the great Mozart, the musical world’s idol, speechless with wonder.

Just when one would now think that Beethoven would make good progress as a musician in Vienna, tragedy struck him. Life, as we all know, has a way of charting its own course for us when we are busy formulating our own plans. In the same way, Beethoven’s stay in Vienna was cut short when he received a letter informing him of his mother’s serious illness back home in Bonn. He went back to Bonn to see her and was at her bedside when she breathed her last on 17th July, 1787, after having suffered a long battle with consumption (tuberculosis). Beethoven was distraught at her death for he had a strong and loving relationship with her and referred to her as his “best friend.” Within some months, Beethoven lost his sister Maria Margaretha too.

For several years after that, Beethoven was constantly in a depressed state. In his letter to his friend, Dr. Von Schaden at Augsburg, Beethoven wrote, “She was indeed a kind mother to me, and my best friend. Ah! who was happier than I when I could still utter the sweet name of mother and it was heard! To whom can I now say it? Only to the silent form which my imagination pictures to me.”

Beethoven stayed back in Bonn as a court musician establishing his reputation as the city’s most promising young talent. With his mother’s death, his father’s drinking habits increased further till matters came to such a stand that the Court authorities stopped entrusting him with money. Since his father had now lost his livelihood, Beethoven had to shoulder the family responsibilities as well as take care of his two younger brothers. So, he petitioned to the Court to have himself made the legal head of the family. In 1789, the petition was granted and he also got half his father’s income to support his brothers. Also, even though he disliked teaching, Beethoven had to take recourse to it in order to manage home. He even played music in public occasionally. Thankfully, as a court musician, he had made many friends like the Von Breunings, Cresseners, Count Waldstein, the Archduke Rudolph, Baron van Swieten and others who extended their help to the family. The Breunings treated him as part of the family. With them, he acquired ways of a natural nobleman with the right culture and superior tastes. Count Waldstein was kind enough to present him with a pianoforte and the much needed hard cash.

Beethoven lived in the age of change – a period of great turmoil. The storming of the Bastille on July 14th, 1789, marked the beginning of the French Revolution. Its ideals of equality and free speech for all rocked Europe. Along with the political turmoil, there were many changes in the arts, science and societal structures. Literature and art flourished during this time.

The world of music was dominated in the 18th century by the Church. With time, music began to be enjoyed by the nobility and they even began learning to play musical instruments. Composers and musicians were servile to the nobility in those days. Beethoven challenged this attitude and remarked, “It is good to move among the aristocracy, but it is first necessary to make them respect.” At one time during a performance, when a nobleman started talking, Beethoven stopped playing his music and declared, “For such pigs I do not play!”

In Vienna, the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II died in 1790. Beethoven, then 19 years of age, was given the rare chance of composing a musical piece in his honour. However for some reason, it was never performed. Nearly a century later, well-known German composer and pianist, Johannes Brahms, discovered that the musical piece by Beethoven entitled “Cantata on the Death of Emperor Joseph II, was in fact “beautiful and noble”. It is now considered as his earliest masterpiece.

The musical genius Mozart died in 1791. The very next year, in 1792, Beethoven’s father too passed away. In the same year, the French revolutionary forces swept across the Rhineland into the Electorate of Cologne. Beethoven decided to make his second visit to Vienna to study with Joseph Haydn, who was then regarded as the greatest composer alive. Prince Elector had taken note of young Beethoven’s exceptional talent and wished that he pursue his musical education in Vienna, and once again sponsored it. Beethoven had finally made up his mind and left the Rhine (Bonn) for good – leaving his home, his friends and Babette Koch, the charming daughter of the proprietress of ‘Zehrgarten’, where he used to have his meals. The political changes that took place in Germany as a result of the French Revolution compelled the change of plans. Beethoven’s two younger brothers also followed him to Vienna, and he took on the role of a father and educator for them.

♪ ♫ MAKING HIS MARK ♪ ♫

♪ ♫ MAKING HIS MARK ♪ ♫

Talent truly knows no boundaries. In the fascinating city of Vienna, Beethoven got the chance to hone his musical talents. He got some excellent teachers – the eminent musicians of the age; he grasped the nuances of the piano with Franz Joseph Haydn,

counterpoint and theory with Johann Albrechtsberger and vocal composition with Antonio Salieri. Violinist Ignaz Schuppanzigh taught the 22 year old Beethoven violin lessons. Though Beethoven was at that time one of the prodigious piano players, his poetic mind was yet to unleash its grandeur and sublime supremacy.

Beethoven could remain with Haydn only for two years, since in 1794, Haydn, who is called “The Father of Symphony” left Vienna for England. Beethoven however did not regret the parting since he felt that Haydn did not give him much attention. The two maintained their friendship although their relationship as student-teacher failed.

In Vienna, Beethoven soon established his reputation as a virtuoso pianist, adept at improvisation. This role was perfect for him since many from the Viennese aristocracy were his patrons and they provided him with the necessary lodging and funds, thereby giving him the security of income and stay.

Since he had already made his mark as a composer and pianist, many of the music-loving Viennese aristocracy who were devoted to art rallied around him. During these times, Beethoven’s temperamental attitudes started to show. Even a fiery temper, a disheveled look, and difference in social status could not prevent the wealthy dilettanti (people with amateur interest in the arts)from showering the choices of favours upon him. Beethoven’s patrons included the Archduke Rudolph (the youngest son of Emperor Leopold II, the Holy Roman Emperor), Prince and Princess Karl Lichnowsky (of Vienna), Prince Lobkowitz (a native of Bohemia), Prince Kinsky (of Bohemia), Count Waldstein (his first great patron since his Bonn days), the Breunings (his family friends) and many more. He played and dedicated music to his patrons and freely mixed with them in their houses as if they were his own.

On 29th March,1795, Beethoven gave his first public performance as a young adult of 25 years in Vienna, where each musician played his own work. Beethoven’s earlier performances were at palaces and mansions and his fame had reached the public. They clamoured to hear Beethoven. This performance was at a charity concert in aid of the widows and orphans of musicians and was supported by the Artists’ Society in the Burg Theatre. Beethoven played his “first” piano concerto in C major and made a tremendous impact in the world of music and in the eyes of the Viennese people.

He ended up making the Austrian capital of Vienna his permanent residence.

Soon afterwards in the same year, Beethoven published a series of three piano trios as his “Opus I” – the three trios for pianoforte, violin and violoncello, which won huge critical and financial success for him. It was dedicated to Prince Karl Von Lichnowsky. The late Mr. Ella (Founder and Director of the Musical Union, predecessor of the Popular Concerts) described it as “a veritable chef d’oeuvre of originality, beauty, symmetry and poetical imagery.” Haydn first heard Beethoven’s Opus I played at Prince Lichnowsky’s in front of the amateurs as well as the artists of Vienna. Haydn felt that the C minor Trio was “music of the future”, not suited to the present time. Hence, he advised postponing the publication of the C minor Trio. Beethoven took offence and thought that Haydn was just plain jealous.

Even Beethoven’s association with Albrechtsberger, the famous contrapuntist, was short-lived. The master wanted discipline and the pupil could not put up with it and hence inn 1795 they drifted apart. Thus Beethoven’s tutelary experiences reached an end. Music composers Antonio Salieri and Emanuel Aloys Forster, a Silesian, helped him with their knowledge, but there was no more regular study under any master.

Beethoven visited Prague, Nuremberg and Berlin in 1796, and Prague once again in 1798. He spent the rest of his time in Vienna, his beloved city where he had made many acquaintances. He was much admired and loved by the aristocracy and the music lovers of Vienna.

THE TENDER EARLY NOTES ♪ ♫

The world of music is a world of delight; it encompasses mankind. Beethoven reveled in this highest form of art and expressed himself in it. However, around 1798, at the age of 28, came the first signs of his loss of hearing. This was just before he wrote his first symphony. The years around 1800 is traditionally called the early period of his musical career. In this early period, he was still trying to master the high classical style.

On 2nd April, 1800, in the first spring of the new century, Beethoven gave his first Akademie (benefit concert) in the Royal Imperial Court Theatre in Vienna beside the Burg. The presentation of his first symphony (Symphony No.1 in C major) was done here. This graceful and melodious classical work by a young Beethoven showed that he was already charging into new ground with his music and was becoming one of Europe’s most celebrated composers. However, due to the rivalries between the artistes engaged for the show, the performances were not up to the mark. In later years however, Beethoven disliked this piece saying, “In those days I did not know how to compose”. Yet the years 1800 and 1801 were creatively active ones for Beethoven.

In 1801, a boy named Czerny became Beethoven’s pupil. Czerny, under Beethoven’s tutelage learnt a lot and Beethoven regarded him almost as a son.

As the new century progressed, Beethoven’s musical compositions scaled high with maturity, marking him as a masterful composer. In 1801, his “Six String Quartets” were published. The quartets exhibited his complete mastery of this very difficult and cherished of Viennese forms developed by Mozart and Haydn. Beethoven also composed “Die Geschöpfe des Prometheus” (The Creatures of Prometheus), a wildly popular ballad in the same year. It was performed 27 times at the Imperial Court Theatre.

Misfortune struck Beethoven in 1801 when Maximilian Franz, the Elector of Cologne, who was one of his patrons, passed away. With his demise, the bounty which he bestowed upon Beethoven also stopped. And therefore, Beethoven now began to work as a means for daily sustenance.

THE DEAFENING SILENCE

Beethoven was a little over 30 years of age now. He was the musical genius and an idol of the Viennese, sought by the highest and the noblest in the land. With the turn of the century, Beethoven was struggling to hear the words spoken to him. He admitted his fear to his friends that he was slowly becoming deaf.Earlier, he did have some symptoms, but now they were without doubt grave! The thought that he was growing deaf! A depressing and horrid thought for anyone, but even more so for a musician whose life was music! Imagine not being able to listen to music - his passion in life?

Beethoven’s fear was proved true. Many doctors were consulted, many remedies tried, but there was no complete relief. In the search for a cure for his deafness, Beethoven tried all he could. From a village near Vienna, Beethoven wrote, “The fond hope I brought with me here of being to a certain extent cured, now utterly forsakes me. As autumn leaves fall and wither, so are my hopes blighted. Almost as I came, I depart. Even the lofty courage that so animated me in the beautiful days of summer is gone forever. O Providence, grant me one day of pure felicity. How long have I been estranged from the gladness of true joy? When, O my God, when shall I again feel it in the temple of nature and of man? Never! Ah! That is too hard.”

Pastor Amanda, a very good friend of Beethoven tried to console him but in vain. What was worse was Beethoven even grew ashamed of his deafness and implored those who knew of it to keep it under wraps. Within two years, Beethoven, the giant musician was almost totally deaf. In 1801, in a heart-breaking letter to his physician friend Franz Wegeler, Beethoven confessed, “My ears continue to hum and buzz day and night…at a distance I cannot hear the high notes of instruments or voices…I must confess that I lead a miserable life. For almost two years I have ceased to attend any social functions, just because I find it impossible to say to people : I am deaf. If I had any other profession, I might be able to cope with my infirmity; but in my profession it is a terrible handicap.”

Many a times, Beethoven suffered extreme melancholy due to his condition. From the seriousness in his boyhood, he had now grown into a complex man with personality disorders. He even had suicidal thoughts many times, but fate intervened in the form of a quote he read somewhere. As he said,

“If I had not read, that man must not of his own free will end his life, I should long ago have done so by my own hands...I may say that I pass my life wretchedly. For nearly two years, I have often already cursed my existence.”

At times he would be rude and violent, at other times kind and generous. He raised funds for the poverty-stricken only surviving child of Johann Sebastian Bach and made and donated new compositions for a benefit concert in aid of Ursuline nuns.

Beethoven’s temper is legendary. Stories abound as to how he threw hot food at a waiter, swept candles off a piano during a bad performance and how he may have hit a choirboy.

His intense temper played out even in his family life. Even though he had a fiery temper, Beethoven had many friends. Over time, he became absent-minded, greedy and suspicious to the point of paranoia. He feuded with his relatives, friends and business acquaintances – his brothers, his publishers, even his patrons and pupils were on the receiving end many times. Once he even tried to break a chair over his closest loyal friend and patron, Prince Lichnowsky’s head. Another time, at Prince Lobkowitz’s palace, he stood in the doorway and shouted for all to hear, “Lobkowitz is a donkey!”

Perhaps it was because of his preoccupation with the need to create good music and at the same time, losing the world of sound as a result of his deafness, that he became short-tempered. Inspite of it, his music drew admiration and respect for him. His renditions moved his listeners to tears. But to quote Beethoven, “Composers do not cry. Composers are made of fire.” His musical talent served as a shield for his sudden spurts of anger and impulsive behaviour.

Even in the face of this adversity, Beethoven did not lose faith in existence. The worsening of his handicap did not dampen his musical spirit. In fact, he brought forth some great Sonatas for Piano, like The Tempest (Piano Sonata No.17 in D Minor, Opus 31, No.2) and The Moonlight Sonata (Piano Sonata No.14 in C-sharp minor, Opus 27, No.2) during this time. The early period of Beethoven’s musical career culminated in the Second Symphony (Symphony No.2 in D major, Opus 36), a symphony in four movements, mostly written during his stay at Heiligenstadt, a small village on the banks of River Danube, in outer Vienna, in 1802. Beethoven moved to this village in April 1802, on his doctor’s orders to be in tranquil surroundings, away from the hustle-bustle of city life. “The Heiligenstadt Testament” was written at the end of this prolonged summer stay.

In The Heiligenstadt Testament, a letter written to his brothers dated 6th October, 1802, Beethoven described his trauma poignantly. In it he wrote, "O you men who think or say that I am malevolent, stubborn or misanthropic, how greatly do you wrong me. You do not know the secret cause which makes me seem that way to you and I would have ended my life — it was only my art that held me back. Ah, it seemed impossible to leave the world until I had brought forth all that I felt was within me." The testament documented the fact that in despair, Beethoven did think of ending his life.

In early 1803, Ferdinand Ries came to Vienna from Bonn, since the court orchestra at Bonn had been disbanded after the dissolution of the Bonn Electoral Court by the French. He had brought along a letter of introduction from his father, Franz Anton, who had taught Beethoven in his early days. Ries became Beethoven’s pupil and also worked as his secretary and copyist. Once, when Beethoven was out on his favourite country walk with Ries, the pupil drew his master’s attention to the sound of the shepherd’s pipe, but alas! Beethoven was at a disadvantage to hear it. Beethoven has been quoted as having said,

"How great was the humiliation when one who stood beside me heard the distant sound of a shepherd's pipe, and I heard nothing; or heard the shepherd singing, and I heard nothing. Such experiences brought me to the verge of despair;--but little more and I should have put an end to my life. Art, art alone deterred me."

THE HEROIC MIDDLE NOTES ♪ ♫

The years 1803-1812, are known as Beethoven’s “middle” or “heroic” period. During this period, he composed beautiful music, developing and enhancing the classical style into a complex, dynamic and original one. He composed an opera, 2 sextets, 4 solo concerti, 4 overtures, 4 trios, 5 sets of piano variations, 5 string quartets, 6 string sonatas, 6 symphonies, 7 piano sonatas and 72 songs. The most well-known among these are the symphonies No.3 – 8. Beethoven also wrote Romance for Violin and Orchestra No.1 in G major, Opus 40 and Romance for Violin and Orchestra No.2 in F major, Opus 50. These pieces were called romances for they had a light, sweet tone and could be sung as well as played.

The “Kreutzer Sonata” (Violin sonata No.9, Opus 47) was performed in 1803. Beethoven’s oratorio concert, “Christus am lberge” (Christ on the Mount of Olives, Op.85) portrayed the emotional turmoil of Jesus in the Gethsemane garden before his crucifixion. It was first performed on 5th April, 1803.

The “Eroica (Italian for “heroic”) symphony” (Symphony No.3 in E flat major, Opus 55), was a large-scale work with emotional depth and structural rigor. Eroica was initially dedicated in honour of a great man, Napoleon Bonaparte, the First Consul of France, who Beethoven admired, for he represented everything noble and glorious in humans. Napoleon had, with his own initiatives and daring, liberated men from tyranny and defied oppressive governments.

In May 1804 Napoleon proclaimed himself the Emperor of France. Beethoven was very angry at this and tore away the dedicatory title page of Eroica, exclaiming, “Is he then too nothing more than an ordinary human being? Now he too will trample on all the rights of man and indulge only his ambition. He will exalt himself above all others, become a tyrant.” Beethoven grew disillusioned with Napoleon and now abhorred him.

Later on, the title “Sinfonia Eroica, Composed to Celebrate the Memory of a Great Man” was inscribed by Beethoven. However, the Eroica Symphony was neither about Napoleon nor related to his memory. It was all about the beauty and structures of music. It was performed for the first time on 7th April, 1805. After the first performance of the Eroica, Haydn is said to have famously declared, “Music will never be the same again.”

Beethoven’s creative activity was intensified in these years. Many compositions like the “Coriolan Overture” and the well-known “Fur Elise” were composed by him. He taught music to many young, attractive students, and even fell in love with many of them.

One of his students was the Archbishop Rudolph, brother of the emperor, who also became his friend and ultimately one of his benefactors.

Beethoven also finished writing his only opera, “004Ceonore” during this time. He wrote and re-wrote four different overtures, and changed the name of the opera to “Fidelio”, though the composer was against it. “Fidelio” (Op.72) was a German opera in two acts. It opened before a small audience of French officers on the 20th of November, 1805, as Napoleon had captured Vienna for the first time. For artists, the arts have been an instrument for championing human rights. Beethoven’s music was also used to comment on the social issues prevailing then. Fidelio was set in Spain and told the story of a nobleman who threatens to expose the crimes of a politician and gets unjustly imprisoned in the process.

Beethoven’s single ‘Violin Concerto’ is regarded as the most exalted of all concertos for any instrument. It was much longer and complex than any such previous work. It eclipsed the earlier works in its composition of symphonic thought and expansiveness of gesture. Beethoven wrote the Concerto specifically for the virtuoso violin soloist Franz Clement. The Violin Concerto was deeply lyrical, with finely tuned phrases and poetry, all reflecting Clement’s special playing abilities.

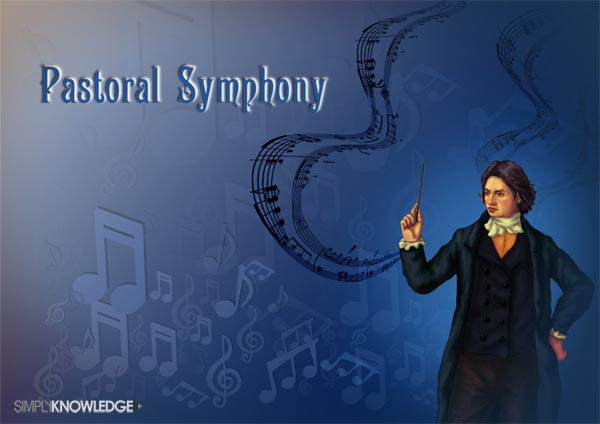

Symphony No.5 in C minor, Opus 67 is one of the most popular compositions in classical music. Symphony No.6 in F major, Opus 68 is also known as the Pastoral Symphony and contains explicitly programmatic content. At the time it was composed in 1808, Beethoven’s personal life was in utter turmoil. His relationships were stormy and his growing deafness caused him much stress.

He really loved to spend time in the woods outside Vienna. He wrote in his diary, "How glad I am to be able to roam in wood and thicket, among the trees and flowers and rocks. No one can love the country as I do. My bad hearing does not trouble me here."

The astonishing and tremendous output of these years inspite of his growing deafness is nothing short of a miracle, and this period in Beethoven’s life is unparalleled in history by any other composer. The pains of real life got channeled into the beauty of his art. Art is said to be an outlet for depression and anxiety; and Beethoven activated this outlet, since to him, music was life, and his thoughts, feelings and ideas found expression in his musical art and flowed out creating beautiful sound waves.

In the fall of 1808, Beethoven was offered the position of Chapel Maestro at the Court of Jerome Bonaparte, the King of Westphalia and Napoleon’s brother. Prior to this, he had applied, upon Prince Lobkowitz’s advice, for a position as permanent composer of the imperial theatres in Vienna, but the aristocracy of Vienna did not accept his proposal. This had left Beethoven with feelings of resentment. The financial advantages which he could get at Kassel (the capital of Westphalia) made him want to accept the position. Hence Beethoven wished to leave Vienna in the year 1809. But his good friend, Countess Anna Marie Erdody, with the help of the Archbishop Rudolph, Prince Lobkowitz, and Prince Kinsky, kept him at Vienna. These men were wealthy admirers of Beethoven and they decided to give him 4000 florins as annual grant, so that he could live well without financial difficulties. The only condition they laid was that Beethoven should not leave Vienna. Beethoven accepted their offer. With the grant of 4000 florins, he became the world’s first independent composer. Earlier, even musicians and composers like Bach, Mozart and Haydn were part of the domestic staff in the houses of wealthy aristocratic families, with the additional work of composition and performance. On the contrary, Beethoven was a free man in respect that he could write at his own pleasure, whatever and whenever he wished.

Inspite of creating such beautiful music and having many friends, Beethoven led a lonely and miserable life. He was highly popular among women due to his musical talent and larger-than-life personality. However, he remained unmarried throughout his life though he was attracted to many women. It could be due to his extreme shyness or his not so fortunate physical appearance or his hearing disorder which affected his social interactions. His outbursts of anger and bad temper could also be one of the many reasons.

In the year 1812, Beethoven went for hydrotherapy at Teplitz, a Czech resort. It is here that he wrote “The Immortal Beloved”, his ardent letter to the woman he loved. Biographers and researchers have speculated much as to the identity of the mysterious woman, even proposing many amongst his students and friends as the recipient. Though Beethoven had a number of affairs in his life, he was ultimately said to be desperately in love with a married woman by the name of Antonie Brentano, who had broken up with him and married a friend. The Immortal Beloved, a beautiful love letter written over the course of two days in July 1812 is supposedly addressed to her.

It was in Teplitz that Beethoven got introduced to poet Johann von Goethe, by his companion Bettina Brentano in July 1812. Though the two great men admired each other, they did not understand one another. Goethe thought that Beethoven was “completely untamed” whilst Beethoven found Goethe “too servile”. Due to his admiration for Goethe, Beethoven put several of his poems to music. During the same time Prince Lobkowitz, one of Beethoven’s benefactors, fell into difficult times financially. Prince Kinsky, another benefactor, died after he fell from his horse and his descendant stopped the financial obligations given to Beethoven. Thus, Beethoven’s financial independence began to sink.

Around this time, Beethoven’s deafness reached a stage where he could no longer perform. This great calamity brought upon him many losses and he had to make several sacrifices, like giving up piano-playing and conducting. However, since the music lovers of Vienna clamoured to see and hear him, it was only until 1813 that Beethoven kept himself away from public pianoforte-playing. Beethoven did plan some orchestral concerts later but music to his ears seemed like “noise”.

Later, Johann Nepomuk Maelzel, the genius inventor from Czechoslovakia contacted Beethoven. Earlier too, Maelzel, the “Court Mechanician” had met Beethoven and helped him with his hearing by his creation of various devices – acoustic cornets, a listening system linking up to the piano.etc. Maelzel had also made the “pan harmonica” (or “pan harmonicon”), a mechanical instrument with the help of which Beethoven composed his work, “The Victory of Wellington” in 1813. Johann Maelzel was the one who invented the musical chronometer, which Beethoven loved very much. He composed a little canon to the words “Ta ta ta (indicative of the chronometer’s beat) lieber lieber Maelzel.” Maelzel later refined it to the metronome, a device that can be set to a specific pace to guide the musician. The metronome was the most significant instrument of all made by Maelzel for it helped evolve music. Beethoven took an immediate interest in it and noted conscientiously the markings on his scores, to enable himself to play his music as he wished.

In 1813, Beethoven first performed his composition The Victory of Wellington, a short single-movement work for orchestra. Another of his symphony, the Seventh was premiered on the same concert. The Victory of Wellington was also called sometimes as the “Battle” Symphony since it simulated the sounds of battle and was a celebration of British victory over Napoleon in the Peninsular War. The Victory of Wellington was written by Beethoven for a gala benefit concert in Vienna for Austrian and Bavarian soldiers wounded in the Battle of Hanau.

Beethoven led rehearsals and even played the piano till the year 1814. It is possible that he felt the “vibrations” of the music in his being and “heard” it. Around this time, Beethoven wrote the final version of “Fidelio”, his only opera, which was an eventual success.

Then the Congress of Vienna (1814-1815) met, which brought together all the heads of European states to decide the future of Europe after Napoleon’s defeat. Beethoven’s glorious moments of pride came when he was invited to play many times, and won admiration and recognition for his compositions.

Kaspar Karl, Beethoven’s brother, died on 15th November, 1815. His brother’s decision to bestow guardianship of his son, 9-year old Karl to both, his wife, Johanna, and Beethoven, changed the course of 45 year old Beethoven’s life dramatically. As with his earlier roles of taking care of his brothers, Beethoven took this role also seriously. A bitter custody battle followed with his sister-in-law Johanna, over the custody of Karl van Beethoven, his nephew and her son.

THE SUBTLE LATER NOTES ♪ ♫

From 1816, the late period of Beethoven’s musical career began. Though the music of this period is less dramatic and more subtle, it also sounds mature and secure. The clear attitude and genius of age is heard here.

Carl Czerny, an earlier student of Beethoven, became young Karl’s music teacher in 1816. He however did not find as much talent in Karl as Beethoven hoped for. At this time Beethoven ended his cycle of lieder “To the distant loved one”, and drafted the first theme for his Ninth Symphony.

Beethoven lost his hearing completely in the last decade of his life. To a composer of beautiful music, losing the sense of hearing – a sense that matters most to a musician, was perhaps the most shocking and depressive truth, a challenge he had to confront and rise from. Yet he managed to compose some works during this time.

In 1818, the Archduke Rudolph became the Cardinal. Beethoven then began composing his mass in D, a rich work, though it was never ready for the intonation. In the meantime, the legal battle between his sister-in-law and himself went on for seven years leading to ugly defamations on both sides. Finally, Beethoven won the custody for his nephew Karl. But as someone who could not hear and was at best only a single parent to Karl, he found it difficult to understand the growing needs of a child and then a young man. Numerous troubles came up due to the generation conflict and it was hard for Beethoven to win the boy’s affection.

In 1822, Italian composer Gioachino Rossini triumphed in Vienna and his operas were a rage with the audiences. He met Beethoven but due to his deafness and the language barrier, they could exchange only a few words in writing. The Viennese composer thought Italian opera lacked seriousness and tolerated it only in moderation.

THE NINTH SYMPHONY ♫ ♪

Inspite of his complete deafness, his disorderly personal life and growing physical infirmity, Beethoven composed his greatest music in the late stage of his life. In 1823, along with ‘Missa Solemnis’, the Ninth Symphony was also almost finished. “Missa Solemnis”, a mass that debuted in 1824 is among his greatest late works. String Quartet No.14, containing seven linked movements played without a break is also among his finest achievements. His most towering achievement is the Ninth and final Symphony (Symphony No.9 in D minor, Op.125), which was completed in 1824. In the later years of his life, Beethoven rarely wielded the baton. However, he attempted to conduct the first performance of his “Ninth Symphony” on 7th May, 1824. After this performance in which a stone-deaf Beethoven led his band of dedicated followers, the scene that followed was one of pathos. The audience was giving a storm of applause since the piece had ended and the orchestra had stopped playing. Beethoven, oblivious to the same, continued conducting Vocalist Mdlle. Caroline Ungher, a famous 19th century soloist who was singing in the performance, took Beethoven by the hand then and turned him around to face the audience. The visual treat of thousands of hands clapping together, made Beethoven realize the tremendous effect of his captivating musical composition.

Symphony No.9; a complete piece, was a success and brought Beethoven some financial reward and relative stability in his last years. One of the most famous musical pieces in history, the anthem-like vigour of the choral finale and the concluding invocation of “all humanity” were inspiration for the masses. The symphony’s contrapuntal and formal complexity delighted music connoisseurs.

THE SETBACKS IN LIFE

This late period of Beethoven’s life showed lack of funds since his former patrons could no longer support him. Beethoven had financial problems and whatever money he had saved, he used it for his nephew Karl. However, the relationship between Beethoven and his nephew Karl was tense and troubling.

Later, the period of the last quartets of Beethoven’s music began, which are difficult to interpret even for the audiences of today. He began to compose his tenth symphony.

Beethoven transported his listeners to seventh heaven with the divine sounds of music he composed. It is easy for anyone with an ear for music to empathize with him on his great misfortune. In his letters, Beethoven has written, “I will grapple with fate; it shall never drag me down; I will seek to defy my fate, but at times I shall be the most miserable of God’s creatures.”

In 1825, Theodore Frederic Molt, a German musician who was living in Montreal then, went to pay his respects to Beethoven in Vienna. Beethoven presented Molt with a canon (a tiny composition), which is a type of polyphony (the use of two or more musical lines at the same time), on a scrap of paper. Molt returned to Quebec with Beethoven’s canon but after Molt’s death it was not to be found. It was found after a hundred years and more in New York City.

The creative strength of Beethoven burst forth breaking all restraints and asserted itself in his music in a way that otherwise might not have been demonstrated. At this time he had written, “I live only in my music.”

On 30th July, 1826, unable to cope with the tense atmosphere at home, his nephew Karl sought escape from it. To his distressed mind, suicide seemed to be the best escape route for him to get away from the family animosity. He tried to commit suicide, but was fortunately found in the nick of time and taken home to his mother to recuperate. He was later hospitalized and given religious instruction to inculcate positivity in him and bring back his zest for life.

THE TOTAL SILENCE

In October 1826, as he was putting to finish his last complete string quartet, Opus 135, the journey of a lifetime weighed down heavily upon the music maestro. Beethoven had a premonition that he would not survive this illness. During his last illness, his nephew Karl reconciled with him.

At this time, Beethoven’s youngest brother, Nikolaus Johann was staying in the Lower Austrian village of Gneixendorf near Krems. He invited Beethoven to his country estate “Wasserhof”, to escape the wagging tongues of society in the aftermath of Karl’s attempted suicide. Though initially Beethoven refused, but later when Nikolaus called the second time, he went there with his nephew Karl, after the latter’s return from the hospital in the fall of 1826.

Whilst his stay there, Beethoven composed the last complete piece of music he was ever to compose: the replacement final movement for the Late Quartet Opus 130 (in place of the Grosse Fuge). The brothers had frequent rows and Beethoven’s stay at the estate was tension-filled, compounded by his failing health.

After having argued again with his brother, Beethoven returned from his brother’s estate in an open wagon to Vienna in November 1826. He was struck with pneumonia by the time he reached home. This further complicated his already existing health problems. Beethoven now was suffering more than ever from his physical and psychological infirmities and thought nostalgically of his youth. He acknowledged this in a letter written to his childhood friend from his Bonn days, physician Franz Gerhard Wegeler on 7th December, 1826:

"If we drifted apart, that was due to the nature of our lives. Each of us had to pursue his intended purpose and seek to attain it. Yet the eternally unshakable foundations of what is good always held us strongly together....my beloved friend!...I need hardly tell you that I have been overcome by the remembrance of things past and that many tears have been shed while the letter was being written."

The sick and ageing composer’s nostalgic vision of his past – his early years at Bonn and the fond memories of old friends were revealed in his letter. In January 1827, when Beethoven wrote his will, Karl became the sole beneficiary of his estate.

Music to a musician is his heart and soul…and Beethoven was not able to listen to his own heart and soul…his music. Can there be anything more tragic than when an artist is not able to hear his art; listen to his soul speak? The loneliness and depression he must have had is palpable.

Beethoven became bedridden for most of his remaining months. He was never to fully recover from this. During his last days, whilst on the threshold of imminent death, Beethoven summed up his life by a tag line that Latin plays at the time concluded with. He said, “Plaudite, amici, comoedia finitaest.” It means “Applaud friends, the comedy is over.”

In the late afternoon of 26th March, 1827, Beethoven was surrounded by his closest friends on his bedside. The sky became dark and a lightning flash lit Beethoven’s room suddenly. A loud thunder clap followed it. Opening his eyes, Beethoven raised his fist and fell back dead. He was 56 years old. Beethoven had to carry the terrible burden of deafness to the grave. His last words were “I shall hear in Heaven.”

During autopsy, it was revealed that there was post-hepatitic cirrhosis of the liver. This was due to his addiction to alcohol. The auditory and other related nerves were also considerably dilated. The autopsy also provided clues to the origins of his deafness, tracing it to his contraction of typhus in the summer of 1796.

The composer’s body was blessed by nine priests. His funeral took place three days later on March 29 in the Währing cemetery, north-west of Vienna, after a requiem mass at the church of the Holy Trinity (Dreifaltigkeitskirche). Stephan and Gerhard von Breuning along with eight leading Austrian musicians were the pallbearers. Austrian composer Franz Schubert, who greatly admired Beethoven, was one among them. Soldiers had to control the grieving crowd of twenty thousand people who had lined the streets to pay their respect to their beloved composer. The funeral prayer was from a poem by Franz Grillparzar, a great writer. It was read by actor Heinrich Anschütz in front of the doors of the Wahring cemetery. The final part of the prayer was quite prophetic:

“He who comes after him will not follow in his footsteps; he must begin anew, for this innovation has finished his life's work at the limits of art."

Beethoven’s remains were later transferred to Vienna’s Central Cemetery. His grave is marked by a simple pyramid on which one word has been written - “Beethoven”.

Beethoven’s life had been like a grand symphony with music playing a strong role in the notes of his life, however the circumstances. He left behind a legacy of music which uplifts every soul. As Beethoven remarked once to his benefactor Prince Karl Lichnowsky directly,

“Prince, you are what you are, through the accident of birth; what I am, I am through myself. There have been and there will be thousands of princes; there is only one Beethoven.”

AFTER DEATH

In 1862, Beethoven’s remains were exhumed for study and moved to Zentralfriedhof in Vienna in the year 1888. There has been considerable dispute regarding the cause of Beethoven’s death. Locks of his hair were clipped by friends and visitors during his last days and after his death. The analyses of these hair clippings as well as the skull remains which were exhumed in 1862 have led to the hypothesization that Beethoven through the excessive doses of lead-based treatments by his doctor was accidentally poisoned to death. But these findings were mostly discredited.

Canadian music composer and violinist, Alexander Brott’s composition ‘Paraphrase in Polyphony’ has an interesting story behind it, relating to Beethoven. The scrap of paper on which Beethoven had presented German musician Theodore Frederick Molt with a canon, a tiny fragment of music in 1825, was found in New York City in the year 1966. Alexander Brott, who was in Montreal learned about this discovery. After examining Beethoven’s canon, he wrote his ‘Paraphrase in Polyphony’, a 20-minute full-length composition, which has an excerpt based on this canon.

‘The Moonlight Sonata’, the second of two sonatas making up Opus 27, is one of Beethoven’s most popular compositions. When poet Ludwig Rellstab said that it reminded him of moonlight rippling on the waves of Lake Lucerne in Switzerland, it became known as the ‘Moonlight Sonata’. This was much after Beethoven’s death.

♫ ♫ THE GRANDIOSE OF HIS MUSIC ♫ ♫

“You will ask me where I get my ideas. That I cannot tell you with certainty; they come unsummoned, directly, indirectly,--I could seize them with my hands,--out in the open air; in the woods; while walking; in the silence of the nights; early in the morning; incited by moods, which are translated by the poet into words, by me into tones that sound, and roar and storm about me until I have set them down in notes.”

Simply put, an artist sometimes cannot really explain how the inspiration into drawing a certain sketch, compose a certain musical note, or a piece of prose or poetry develops. They come in flashes of insight at any time; sometimes even in the state of dream and compel the artist, musician, writer or poet to include it in their art; just as it did for Beethoven.

In the mid 18th century, symphonies conformed to the structural rigidity and rationality of form. The genre’s humble beginnings consisted of three small movements of about ten to twelve minutes. Through his nine symphonies, Beethoven changed the concept of what a symphony should be like. He extended the time frame and formal dimensions of his symphonies. While his Third Symphony lasted about 50 minutes, the Ninth Symphony ran over an hour. Beethoven added more instruments, the harmonic language he created was much bolder and helped to heighten the emotional intensity of his symphonies, each of which is a masterpiece. Even among these, the Third, Fifth, Sixth and the Ninth are ranked as the greatest.

Beethoven’s First Symphony was brought out at the turn of the century. His symphonies had a novel and indescribable feel. Beethoven’s Symphony No.3 ‘Eroica’, his most original and grandest work till date, was completed in the year 1804. It was unlike any music composed before and even after weeks of rehearsals, the musicians were at a loss how to play it. Eroica showed the structural beauty of music; how notes are formed into musical and groups of cells, phrases, paragraphs and high edifices in sound. Eroica was proclaimed by an eminent reviewer as “one of the most original, most sublime, and most profound products that the entire genre of music has ever exhibited.”

When Symphony No.5 was created in 1808, it was a “modern” work of art for those times. It is now the world’s most popular symphony played countless times. In the opening movement, there wasn’t even a single hummable tune. Listeners instead were left gasping under the concentrated intense onslaught of the famous “da- da- da-daaah”- a four-note rhythmic cell which unfolded with great energy. Such was the emotional impact of Beethoven’s music.

Beethoven's Symphony No. 6 (Pastoral) is also one of the world’s greatest symphonies. It was also composed in 1808 and showed Beethoven’s love for the beautiful countryside. One of the turbulent forces of nature, the storm was given apt rendition here. This symphony showcased one of the most famous storms in music history. It began with the falling of a few raindrops, the gushing of wind, and then the heavens bursting open, sending rain down in torrents. The lashing of the wind and the flashes of lightning were depicted very well. Trombones were used here and also the shrill piccolo and the undering timpani (drums). Perhaps this was Beethoven’s way of showing the passage of the wave of deafness in his life, which started gradually and ended up in a turbulent storm, depriving him of listening to his love; beautiful music.

Beethoven’s Third Symphony did break records, but his Symphony No.9, which premiered in Vienna in 1824, went a lot further. Its cosmic scope embraced the whole world with the immensity of its elemental power, the appeal of its grandeur and the unity of the universal human spirit. It delivered a musical –cum-textual message with the use of a chorus and four vocal soloists; longing for universal brotherhood, joy and peace. This was a special feature which had never before been attempted in a symphony. The “Ode to Joy” by the German poet and dramatist Freidrich von Schiller was an inspiration to Beethoven and he adapted some of its stanzas. The Western world is very familiar with the chorus song – the main theme of the final movement. Though the song sounds naturally simple, Beethoven had to practice nearly twenty versions, changing, sustaining and repeating notes wherever required till he was happy with the end result.

The Ninth Symphony of Beethoven continues to touch the hearts of the people of the world. His Ninth Symphony rang out at the Tiananmen Square protests by students in Beijing, China in 1989. Its rendition was also done during the dismantling of the Berlin Wall in Germany in 1990. The power of music in changing people’s lives is immense and the Ninth Symphony has become a symbol of unity and of love.

beethoven the man

"There is no loftier mission than to approach the Divinity nearer than other men, and to disseminate the divine rays among mankind."

Beethoven had an extraordinary personality. He was a complex man with a genius mentality, made all the more remarkable due to the deafness with which he struggled throughout his life. His unquenchable thirst for making music left behind a legacy of delightful and captivating music.

Though he was lacking in social graces, he was very proud. With the passage of time, Beethoven’s absorption in his music grew to the point where he ignored his grooming too. Instead of washing in a basin, he would pour water over his head. On a country walk, he was arrested by a local policeman who mistook him for a tramp. Beethoven never allowed anyone to touch his manuscripts which were piled high in his room. He had four pianos without legs so that he could feel the vibrations of their music. Many a times, he would work in his most basic innerwear, or even in the nude, and the friends who came visiting would be ignored, since he did not like to be interrupted whilst composing.

A renowned critic of Beethoven has rightly said of the “Letters” containing his thoughts – they “give an extraordinary picture of the mingled independence and sensibility which characterized this remarkable man, and of the entire mastery which music had in him over friendship, love, pain, deafness, and any other external circumstance.”

Ludwig van Beethoven, widely considered as the greatest composer of all time, has attained cult status. The cult has spread through many levels of high, middle, and popular culture in music, art, television, and film. The Beethoven image, now all too commercially viable, is itself the subject of a sizeable literature. And no work has been more fertile in creating and maintaining this image than the Ninth Symphony.

He is the crucial transitional figure connecting the Classical and Romantic ages of Western music. His musical compositions stand along with the plays of the greatest playwright of all time, William Shakespeare, in terms of the peak of human accomplishment. What makes it an even more outstanding act of creative genius is the fact that Beethoven was deaf when he composed his extraordinary soul-stirring music. It perhaps draws a parallel in John Milton, who wrote ‘Paradise Lost’, while blind.

The musicians who preceded Beethoven sought only to please their social superiors and did not think independently. But with Beethoven, things changed. Beethoven used his intellect, had independence of thinking and raised the stature of the artist. He was a genius of a musician with an altruistic spirit. His music spoke to the intellect of mankind. Nature was used as a theme in much of his writing.

There is only one Beethoven, there can never be another like him. He has left his own indelible touch in his music. As he himself said, “I always have a picture in my mind when composing, and follow its lines.”Beethoven, the musician lives on in the musical legacy he has left behind. His music will forever awaken our senses, heal our psyche, soothe our fears and work miracles in us. The language of music cuts across all barriers and binds humanity with its ageless and timeless lyrics. Great maestros like Beethoven are born only once in a while to share with humankind the beautiful gift of creating music which they were blessed and endowed with.

Biography of Beethoven | 0 Comments >>

0 --Comments

Leave Comment.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked.