Scientific Scenario of the World

“In science, we must be interested in things, not in persons.”

---Marie Curie

At the time of Marie Curie’s birth, science was touching new heights as new discoveries and inventions were happening. Charles Darwin, the greatest biologist of all time had published his theory of Evolution and ideas which set the scientific world on fire. His book, ‘The Origin of Species’ by means of natural selection or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life, was published on 24th November, 1859. The general public and the scientists of the world accepted his views on evolution. James Maxwell (Scottish mathematical physicist), Michael Faraday (English scientist) and Ludwig Boltzmann (Austrian Physicist) took the theories of electricity and magnetism ahead during Marie Curie’s time. Dmitri Mendeleev (19th century Russian Chemist and inventor) published his much acclaimed periodic table (tabular display of the chemical elements) during this phase, which is the basis of the one that is currently used in Chemistry. A lot was being discovered and a lot remained to be discovered. This was when and where Marie Curie stepped into the picture.

Formative Years - Of Joys and Tears

“Believe me, family solidarity is after all the only good thing.’’

--- Marie Curie

The Sklodovski family was extremely close knit and supported each other through the thick and thin of their lives. At the young age of four, Marie had mastered the art of reading fluently. She was both precocious and curious as a child and her father’s scientific instruments – the barometer, the tubes, the scales and the gold leaf electroscope were like toys to her that attracted her immensely. She had an exceptional memory and she learned the Russian language along with her native Polish, without any trouble at all. Little Marie was very close to her mother and loved to spend time with her. But unfortunately, after her birth, her mother contracted the much dreaded disease of Tuberculosis. In 1871, Vladislav’s brother had moved in to stay with Marie’s family and the Sklodowska family had no inkling that he had tuberculosis. The disease gradually started getting better of her and spread due to the poor living conditions of the family.

During the autumn of 1873, Marie’s father was removed from the position of principal of the school and was replaced by a Russian. He was a man of self-esteem and would not bow down before the Russians so he was shamed publicly by the Russian authorities. To add to his troubles, he lost most of his savings due to bad investments and the family had to face hard times. They had to shift to a smaller home and to help meet their living expenses, Marie's family took in student boarders. One of the boarders infected Bronya and Zosia with typhus in 1874 and Zosia, Marie’s eldest sister could not fight the fever and passed away. Marie was just eight years of age when she lost her sister.

As we know Marie’s household was highly crowded, with too many people living in one small apartment, these crammed up living conditions helped on to spread tuberculosis, which was a major infection and killer disease in the late nineteenth century. Sadly for Madam Sklodowska, she could not kiss or hug her children for the fear of transmitting the disease and most often the older kids would look after the younger ones. When Marie was very small she would often miss her mother who would be away travelling to warm places like the south of France, in a hope to cure herself. Whenever Bronislawa was at home she would stay in a separate room, away from the children’s room. This was very heartbreaking for a child of Marie’s age because it deprived her of her mother’s love and affection. After several expensive cures Bronislawa could not fight the onslaught of her illness and succumbed to it in 1878 when she was just 42 years of age. The loss of two loved ones in a very short interval was a major blow to Marie’s family and a curtain of grief fell on the Sklodowskas. Marie suffered from depression and realized very early that life was not a bed of roses. The deaths of her mother and sister caused Marie to give up Catholicism and become agnostic.

Educational Resistance Movement

The Russian invasion of Marie’s part of Poland was strongly opposed by her family. Her father was a part of the Polish resistance movement against Russian authority but he was against armed revolt. He believed in the strategy of passive resistance. Like many other Polish intellectuals he strongly believed in the power of education. He was of the notion that only an educated society could unleash a social revolution; this line of thought was called Positivism. The Polish Positivists advocated the exercise of reason before emotion and believed that independence, if it is to be regained, must be won gradually, by creating a material infrastructure and educating the public. Marie’s family were staunch nationalists who were deeply involved in this educational resistance movement. Despite the watchful eyes of their invaders, Polish teachers found ways to teach their own language and history. Marie was educated even in these difficult times and it can be said, that life was a fight for her from the very start, which she eventually won.

Introduction

“Life is not easy for any of us. But what of that? We must have perseverance and above all confidence in ourselves. We must believe that we are gifted for something and that this thing must be attained.”

--- Madam Curie

For ages a woman's access to higher learning was severely restricted all across the globe. The glorified world of science was mostly male dominated and powerful men opposed the education of women beyond reading and writing their names. If we study the history of inventions and scientific discoveries, we’ll find the predominance of men. King James I of England, successor to Queen Elizabeth, rejected a proposal that his daughter be given a classical education saying, "To make women learned and foxes tame have the same effect - to make them more cunning." There were strong male and female voices of dissent against the intellectual subjugation of women. In 1692, the famous English writer and journalist Daniel Defoe wrote "one of the most barbarous customs in the world, considering us as a civilized and a Christian country, is that we deny the advantages of learning to women.... Their youth is spent to teach them to stitch and sew, or make baubles. They are taught to read, indeed, and perhaps to write their names, or so; and that is the height of a woman's education."

In the nineteenth century one woman dared to challenge this hegemony and proved that women were equally inclined and suited in the field of scientific accomplishments. That remarkable woman was Marie Curie, nee Maria Sklodowska.

A Loving Nest

7th November, 1867, was a special day for Vladislav Sklodowska and his wife Bronislawa Sklodowska as the couple was blessed with their last of five children, a daughter, whom they named Marya. Marya was lovingly called Manya by her parents, brother and sisters all through her life but for the rest of the world she was Marie Curie. Marya’s parents had no clue that their youngest daughter would create history with her achievements and have an amazing future ahead. Marya’s family was an educated family of teachers who stayed in 19th century Poland. Her paternal grandfather, Jozef Skldowski, had been a respected teacher in Lublin and her father, Vladislav Sklodowska was a Polish teacher who taught Mathematics and Physics and managed several schools and reformatory for boys. He was a very well read and knowledgeable person who was regarded as a ‘walking encyclopedia’ by his children. Marya’s mother, Bronislawa, was a teacher and the headmistress of a girl’s school in Warsaw; capital and largest city of Poland. She wielded tremendous influence on the minds and lives of all her children. Marya's father was an atheist whereas her mother, a devout Catholic.

The Sklodowska household had five kids. Marya's older siblings were Zosia, her oldest sister, her brother Joseph, then sisters Bronislawa and Helena. Madam Sklodowska experienced a tough time taking care of her five kids at home as well as managing a large number of kids at school. She was a supermom of her time and it is said that she even made shoes for all her children with her own hands. She was a woman of great beauty and intelligence, who could handle all her tasks with finesse. The Sklodowska family was very scholarly and cultured and these values were passed on to their children who imbibed them well.

In their early years, Marie and her siblings had a comfortable and happy childhood, with exciting holidays in the countryside with their relatives, and lots of love and attention from their parents. But life is transient, so are the moments of happiness and each one of us has to experience the rollercoaster ride of ups and downs in life.

Turbulent Times

“Warsaw was then under Russian domination and one of the worst aspects of this control was the oppression exerted on the school and the child.”

--- Marie Curie

In the late 19th century when Marie was born, Poland was a complex and a tough place to reside in. In the 1790’s Poland was invaded by its greedy neighbours Russia, Austria and Prussia. Poland was a weak nation then and was annexed by these powerful countries which divided it among themselves for power and pelf. The northern part of Poland, where Marie and her family resided was occupied by Russia and it also included the capital city of Warsaw. The Polish people had attempted to overthrow their tormentors on several occasions but were unsuccessful and they were either executed or banished to Siberia if they ever dared to rebel their authority. Entire Polish life was thrown out of gear due to the incursion of policemen, professors and minor dignitaries from Russia. These Russians were watchful of even the smallest traces of rebellion like speaking of Polish language or an indiscreet word about them. Polish intellectuals and teachers were not allowed to openly express their ideas and were told to teach only in Russian language and not in Polish. Life was so difficult for the Poles that they could not even practise their Catholic religion without the fear of being attacked by the Russians. The Polish children were forced to learn Russian history and Russian folk tales in school. Due to this scenario, there was a lot of resentment and unrest in the country which was the homeland to Marie Curie. Marie would often dream of a free nation where all could live happily and peacefully and thus progress well.

The Best Pupil

“We must believe that we are gifted for something, and that this thing, at whatever cost, must be attained.’’

--- Marie Curie

Belonging to a family of teachers, education was always important for the Sklodowska family. Marie started her schooling in a private grammar school. At the age of 10 she was admitted to a public school which was controlled by the Russians. There were lots of restrictions in the school and students were allowed to talk only in Russian language. The teaching was politically correct keeping in mind the Russian authority. Marie’s father had very high hopes for her daughter and she tried every bit to live up to his expectations. She did exceptionally well in school just like her siblings Broyna, Jozef and Helena. She enjoyed learning to the hilt and inspite of the subjects being taught in Russian she progressed well.

Her class was a mix of Polish, Russian and German girls. In school, Marie had found a good friend in Kazia Przyborovska. The two girls would stick together everywhere. In a letter written by Marie to Kazia, when she was 13 years of age, she confessed her love for school. The letter says: “Do you know Kazia, inspite of everything I like school. Perhaps you will make fun of me, but nevertheless I must tell you that I like it and even that I love it.”

During those days in Poland, women’s education was restricted. They were disallowed from enrolling in any Polish Universities like the University of Warsaw. As for careers for women, there were none. If at all any woman thought of ever pursuing a career, she just had the option of teaching in schools. But Marie Curie had other plans for herself and with a strong belief in her heart, she surged ahead in life.

Triumphant Teens

“I was taught that the way of progress is neither swift nor easy.”

--- Marie Curie

Marie was growing up to be an intelligent and hardworking girl just like her brother and sisters. Bronya had won a gold medal for the best student on passing out from school. Her brother Joseph was no different and he too was awarded a gold medal for excellence in school and went to Warsaw University to study medicine. Unfortunately, as women couldn’t study in Warsaw University, Bronya stayed back home to look after the family and run the household. After their mother’s demise there was no one to shoulder the responsibility of the house and Bronya happily devoted herself to looking after her father, brother and sisters. Meanwhile, Marie continued making good progress in school. On 12th June, 1883, Marya Sklodovska graduated from the public school. She lived up to her father’s expectation and was awarded the gold medal as the Valedictorian of her class.

While leaving school she promised to keep in touch with all her school friends forever. Both Marie and her sister Bronya desired to go abroad, to Paris (which was home to many Polish exiles), for higher studies as women’s education was a taboo in Poland. But the financial conditions of the family turned from bad to worse. Marie’s father lost his teaching job and they had to take in many more student boarders to meet out their expenses. He used to teach them in the apartment itself to survive the financial crisis. Nevertheless, all these complexities in life did not dampen the spirits of the girls and they did not cease from dreaming of the future.

A Time off in a Countryside

Marie had worked very hard in school and had exhausted herself completely. Her father decided to send her to a much deserved holiday along with her sister Helena to spend a year with an affluent uncle and aunt at their country estate. This was the only time in Marie’s life when she was not working and simply relishing the good things in life. In the countryside she would go exploring, boating, fishing, swimming and riding horses. She spent time reading novels and not scientific texts which she mostly read. During the winter she enjoyed the sleigh rides through the snow clad countryside and often went out dancing and partying with her cousins and friends. Marie fondly remembered all her life, how at the St. Louis night ball, she happily danced the night away in her new pair of shoes. This entire experience was magical to young Marie who cherished it forever. She wrote to her best friend Kazia: “I can’t believe geometry or algebra ever existed. I have completely forgotten them.”

The Floating University

“First principle: never to let one’s self be beaten down by persons or by events.”

--- Marie Curie

The good times soon ended for Marie and she came back to the harsh realities of the real world. The family’s financial conditions were miserable and she started giving tuitions to wealthy children to supplement the income. The desire to acquire knowledge burnt strongly in her and along with giving lessons she and her sister Bronya got involved in the ‘Floating University’. Started in 1882 by Jadwiga Szczasinska Dawidowa, the Floating University was an illegal night school for young Polish women who wanted to take college education but could not afford to travel abroad for the same. It was called floating because the classes were held in ever changing locations in fear of the Russian authorities who opposed them. The aim of these Floating Universities was not only to educate the students but also to prepare an atmosphere which would finally lead to the Polish emancipation. Although it could not be compared to the standard of European Universities, nonetheless, it provided ample guidance to Marie and led her to the progressive world of science and development. The classes were held clandestinely in private houses and the teachers were all well read historians, philosophers and scientists. Marie would quietly attend the science classes which were held at the Museum of Industry and Agriculture. She would perform experiments in Physics and Chemistry by herself during the weekends and thus started her journey towards her first love; science.

Future Obscurity

Marie’s brother, Joseph, was progressing well in his training to become a doctor. Her sister Helena was still undecided whether to be a teacher or a singer. She was good at both the things and would do well in either of the things or both. As for Bronya, who was twenty now, she was stuck with running the household for four years and couldn’t think about making her future. She wanted to pursue medicine in Paris and then return to Poland and practice as a doctor. However, the family had no finance to fund her ambitions. Marie was very close to her sister Bronya and wished for her dreams to come true. She thought of a plan which would aid in fulfilling their objectives. Marie decided to first work as a governess and support Bronya’s medical studies in Paris and then Bronya after graduating from medical school would in turn support Marie’s studies in science at the Sorbonne University in Paris.

Marie's First Crush and First Heartbreak

“That one must do some work seriously and must be independent and not merely amuse oneself in life – this, our mother has told us always, but never that science was the only career worth following.”

--- Irene Joliet-Curie

The family treated her well and she too enjoyed working with the children. Then came Kazimierz Zorawski, the son of the agriculturist who studied in Warsaw University and was back home for his holidays. On seeing the attractive and talented governess he fell in love with her instantaneously and Marie too fell in love with him. They got engaged and wanted to marry, but Kazimierz’s family forbade him to marry a girl who was penniless. Kazimierz relented to his father’s wish and called off the engagement. This was a major setback for Marie and she was left heartbroken. Due to the financial circumstances of the family she could not leave the job however much she wanted to. She had to support Bronya at any cost and so she put aside all her grievances and continued working. To get over her loneliness she concentrated on self study and took an advanced course in mathematics. Soon, she realized that her interest lay in Mathematics and Physical Science and she started taking Chemistry lessons from a chemist in the beet-root factory. She stayed with them for another two years quietly nursing her wounds and not realizing then that this was a blessing in disguise.

Being a Governess

“There were some very hard days and the only thing that softens the memory of them is that in spite of everything, I came through it all honestly, with my head high.”

--- Marie Curie

Marie taught children of rich families but did not earn enough to sponsor Bronya’s education. It was then that she decided to take up a job as a governess in the house of an agriculturist who lived in a village, 150 kilometres away from Warsaw. Marie was just 18 when she put aside her own ambitions to join as a governess for her sister’s sake. Her employer ran a beet sugar factory and gave Marie the permission to teach the illiterate children of his peasant labourers in her free time. Marie Curie was a philanthropist and she thought not only of her own progress but of the humanity as a whole. With this noble thought in her mind, she started teaching the poor peasant’s children with some help from Bronka, the eldest daughter of the agriculturist who was in her care. Working so far away from home made her homesick but she did not falter for even a second and kept on going as she had promises to fulfil.

A Silver Lining in the Cloud

All these years of hardships and miseries did not weaken Marie but she had beyond doubts, lost all hopes of ever going to Paris. Vladislav Sklodowski retired in 1888 and instead of sitting idle at home he immediately took up a job in a reform school and acted as the director there. It was a well paying job and there was his pension which added to what he was earning. He could now send money to Bronya who was studying in Paris and support his family too. Some money he kept aside for Marie as a compensation for the amount she had been sending for Bronya.

In the year 1890 Bronya was about to complete her medical studies and become a full fledged doctor when she married Kazimierz Dulski who was already a doctor. Bronya who was now in a position to help fulfil her younger sister’s dreams, asked her to come to Paris. However, Marie had still not been able to beat her sadness and there was still some hope alive within her that she might win back her first love if she stayed in Poland. She was still in touch with her Kazimierz and nursed the feelings of love for him. Besides this she also had a strong sense of responsibility towards her family and felt that they needed her help and support. Thus Marie turned down her sister’s invitation to come to Paris and missed her first chance to stepping towards her goals.

A Second Opportunity

“It would be impossible to tell of all the good these years brought to me. Undistracted by any outside occupation, I was entirely absorbed in the joy of learning and understanding.”

--- Marie Curie

Marie was still in Warsaw when an important opportunity came her way. She met her friends from the Floating University and got a chance to study in a secret laboratory. It was kept hidden from the Russian authorities by functioning as a museum in the daytime. At night it served as a laboratory where the young Poles were taught practical science. Till now Marie had only read about scientific experiments, but now she was able to carry them out. She was thrilled to try out the experiments and was now sure about what she wanted to pursue in life. She knew that she was born to become a scientist.

Inspite of Kazimierz’s parent’s disapproval, Marie was in touch with him. Together they went for a vacation in the mountains in the year 1891. Marie was 24 years of age when she realized that her relationship with Kazimierz was going nowhere. He would never commit to her and she was just wasting her time with him in a false belief that he would marry her. She finally broke off and as soon as she reached home from the mountains she thus wrote to Bronya that she was coming to Paris:

“Now, Bronya... Decide if you can really take me into your house, for I can come now. I have enough to pay all my expenses...You can put me up anywhere...I promise I shall not be a bore or create disorder. I implore you to answer...”

She had understood that her true happiness lay in science and started for Paris. Little did she know at that time what good things destiny had in store for her and that she would never live in Poland again.

Paris Calling

After a tiring, two day journey by train she reached Paris in the year 1891. She enrolled herself with the French version of her name, Marie and not Marya, in the faculty of science at the Sorbonne, the renowned University of Paris. She was one of the 23 young women, amongst a total of 1,825 science students. As a student, Marie sacrificed everything for her studies and would not socialize at all. Many of her fellow students did not even know her name because of her reclusive nature. Initially, Marie put up with her sister Bronya and brother-in-law Kazimierz in a small apartment which was an hour’s bus ride from the university. Both of them were working and led extremely busy lives. They practised as doctors from their apartment itself and Kazimierz who was also a Polish activist, would often call his political pals home to discuss politics. Marie’s father felt that such an atmosphere at home was not conducive for her studies and even though Marie loved staying there, she moved into a tiny room which was close to the university.

A Devoted Student

“ Ah! How harshly the youth of the student passes,

While all around her, with passions ever fresh,

Other youths search eagerly for easy pleasures!

And yet in solitude

She lives, obscure and blessed,

For in her cell she finds the ardor

That makes her heart immense.

But the blessed time is effaced.

She must leave the land of Science

To go out and struggle for her bread

On the grey roads of life.

Often and often then, her weary spirit

Returns beneath the roofs

To the corner ever dear to her heart

Where silent labor dwelled

And where a world of memory rested.”

---Marie Curie

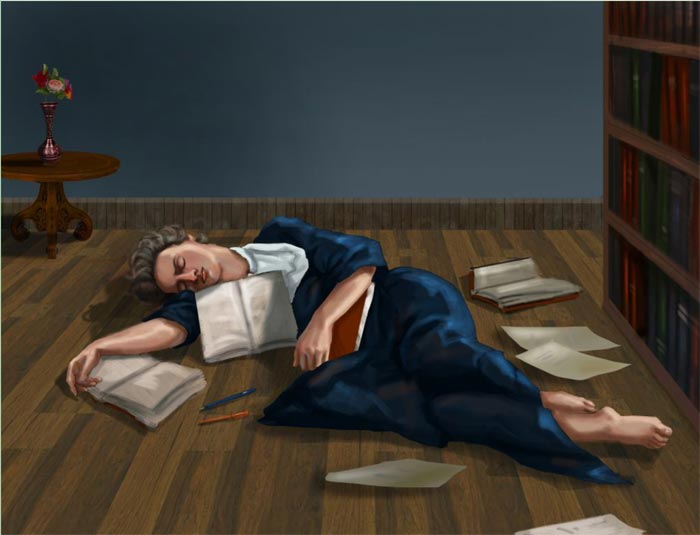

Marie’s sixth floor apartment was in the Latin Quarter on the left bank of Paris. This place’s proximity to the university attracted many artists and students to it. Her living conditions were very difficult but she wasn’t shaken by it. She barely had any money; there was insufficient furnishings and nothing to keep her warm during winters. She did not know how to cook a simple meal and once she even collapsed from hunger as she had forgot to eat while engrossed in her studies.

Bronya and Kazimierz took care of her for a week; they fed her and made her rest. She then returned to her tiny apartment and busied herself in her studies.

She was very happy here as she could live in freedom and study without fear. Her teachers were all highly knowledgeable and her university was a world renowned one. Marie was lucky to be in the right place at the right time. The university had modern labs and new amphitheatre for demonstrations and public lectures. Marie completed her Master’s degree in Physics in the summer of 1893. Clever as she was, she had also perfected her French by now and could speak exactly like a local. When the results of the first year exams were declared, she topped in her class. She then went home for a three month holiday and came back happy and healthy. However, because of the work pressure in the university she started ignoring herself again.

In 1893, her financial condition became worse and her academic career was threatened. Not content with a Master’s in Physics she wanted to pursue a degree in maths also but she had no money for that. Once she wrote in a letter:

“I have literally not a penny – not one! I shall probably not write to you again until the holidays, unless by some chance a stamp should fall into my hands.”

Fortunately for Marie, she was helped by French scientists who recognized her talents and helped her secure scholarship allocated for outstanding Polish students. The Society for the Encouragement of National Industry commissioned her to do a study on the magnetic properties of various steels and for this she needed some lab space. She asked a visiting Polish professor if he could help her in some way and it was then that she was introduced to the French physicist Pierre Curie over tea, by the professor who thought that he could be of some help.

A Meeting Destined to be

“He seemed very young to me, although he was then aged thirty-five. I was stuck by his clear gaze and by the slight appearance of carelessness in his lofty stature...his smile, at once grave and young, inspired confidence.’’

--- Marie Curie (her first impressions of Pierre)

Pierre Curie was a 35 year old physicist, who was born in Paris on 15th May, 1859. He belonged to a close and supportive family just like Marie’s. He had an older brother named Jacques who was a scientist and his father and grandfather were both doctors. His father was an intelligent man who had realized that Pierre was not suited to a normal school so he educated him at home. Pierre had the liberty to learn at his own pace and had a very happy childhood. His mother was an efficient housekeeper who kept the atmosphere in the whole house lively. Pierre was the laboratory chief of the Municipal school of Industrial Physics and Chemistry in Paris. He and his brother Jacques worked together for a number of years and were the discoverer of piezoelectricity.

Marie was introduced to Pierre Curie by the Polish professor in his apartment. It was a meeting that would change not only their individual lives but also the course of science. At that time Pierre was a successful scientist but impoverished. He was single and dedicated himself to science completely. Anything that distracted him from his physics was a nuisance, and he wrote in his diary: “women of genius are rare...” The only distraction which Pierre allowed himself was the love of the countryside around Alsace in north-eastern France. He loved walking and cycling there during his holidays.

Marie was fortunate to get a small space at the Municipal school. Pierre Curie and Marie were drawn to each other in their first meeting itself due to their common love for Physics. Pierre was eight years older to Marie and after several meetings he declared his love to her. He had lost a close female friend some 15 years back and though he had met many women after that, none of them had shared his passion for Physics. Marie was an exception and though they had much in common, yet, there were some differences too. Pierre was a school dropout whereas Marie was the school topper. Pierre was unable to complete his doctorate whereas Marie was very serious about university education. Pierre’s meeting with Marie changed his life for good. He completed his Ph.D thesis and was awarded his doctorate and subsequently promoted to the respectable post of a Professor. He also signed many royalty contracts for instruments that he had designed. Around the same time he proposed marriage to the love of his life, Marie.

Marie took a year to think about her relationship with Pierre and reciprocate to his proposal. She harboured doubts about marrying Pierre as she would have to sacrifice her independence and that would mean cooking and cleaning for the household. Moreover, if she married Pierre she would have to leave her homeland Poland forever, to which she was dearly attached. Pierre was ready to make adjustments and was even ready to relocate to Poland for Marie’s sake. Eventually, Marie realized that destiny had brought them together and they were meant to be with each other as they shared a ‘positivist political and scientific vision’. On 26th July, 1895, they became man and wife in a simple marriage ceremony in Paris. There was no religious service as Marie had become an atheist after her mother’s death and Pierre’s parents too were non-practising Protestant. The couple did not exchange rings and instead of a white, fancy bridal gown, Marie got herself a dark blue dress which she wore as a lab garment for many years. She knew the value of money and could never waste it on herself. About the wedding dress she said: “I have no dress except the one I wear every day. If you are going to be kind enough to give me one, please let it be practical and dark so that I can put it on afterwards to go to the laboratory.” After the marriage the couple went for a somewhat unusual honeymoon. They set out on their bicycles, which they brought from the money given to them as a wedding gift by a cousin, to roam around the French countryside.

Monsieur and Madame Curie

“I have frequently been questioned, especially by women, of how I could reconcile family life with a scientific career. Well, it has not been easy.”

---Marie Curie

Leading a married life was a major challenge to a scientifically inclined Marie. Even though it was a tiny three roomed flat where Marie and Pierre lived, for Marie, managing the household was not an easy task. She continued the research work on the magnetic properties of steel which she found simpler than housekeeping. It is true that whatever Marie did, she did to the best of her ability. As a caring wife she wanted to prepare wholesome and nutritious meal for Pierre, but cooking was a complicated task for her. She would make notes in her recipe book so as not to make mistakes while cooking but she still found it tougher than her research work.

In the summer of 1897, Marie submitted her research results to the society for the Encouragement of National Industry. She received a payment from them, out of which part went to returning the scholarship amount that she had got four years back, not that she had to return it, but she hoped that it would help some other deserving Polish candidate to fulfil his dreams. Thus, continued Marie’s studies and selfless service to humanity even after her marriage. In September 1897 Marie gave birth to her first child, Irene. Pierre’s father was a doctor who helped Marie deliver the baby girl. Immediately after Irene’s birth, Dr. Curie’s wife expired due to breast cancer and he came to stay with his son, daughter-in-law and granddaughter. Marie was lucky to have him in the house as he enjoyed babysitting and she could carry out her work without concern, certain that Irene was in good hands. She found leaving her daughter with a nurse very difficult. Before Pierre’s father moved in, she had to juggle between work and baby and would keep rushing back home from the laboratory, just to see that the child was safe. Now she knew that Irene was being taught and taken care of by her grandfather so it was easier for Marie to concentrate on her work.

A Doctorate for Marie

“I never see what has been done; I only see what remains to be done.”

---Marie Curie (in a letter to her brother)

While Marie Curie was busy trying to handle her family and her research work, there were lots of discoveries being made in the world of science. The French physicist, Antoine – Henry Becquerel made important findings about radiation. On 24th February, 1896, he was the first person to report the radioactivity of Uranium and to suggest the presence of some unknown rays in Uranium compounds. The scientific community was more interested in Roentgen’s (a German physicist) X- rays rather than Becquerel’s (a French physicist) rays. But Marie was pretty much curious about Becquerel’s findings. Since the discovery was recent, the scope for research was very wide and therefore, Marie decided to choose it as her research topic for doctorate. Fortunately, the director of the Paris Municipal School of Industrial Physics and Chemistry, where Pierre was a professor of Physics, gave her a crowded, damp storeroom to use as a lab. However, Marie was the happiest soul when she could quietly get to work in a laboratory, irrespective of the size and ambience. She even said once, “I am among those who think that science has great beauty. A scientist in his laboratory is not only a technician: he is also a child placed before natural phenomena which impress him like a fairy tale.”

The next many years of Marie’s life were spent in the darkness of her small, gloomy and damp laboratory. She worked tirelessly on radioactive elements along with Pierre.

The working conditions in Marie’s makeshift laboratory were very poor and she had to try hard to keep everything in order. She had an ionization chamber, an electrometer and piezoelectric quartz which were a simple set of apparatus. It was known that the pitchblende ore had properties similar to Uranium so the Curies picked this ore for their research. Much to the joy of the Curies, they discovered the presence of a substance in the ore which gave off more radiations than even pure Uranium. This suggested that the phenomenon was not unique to Uranium and it needed its own special name. The term radioactive was then coined by Madam Curie. Marie wrote to her sister Bronya about their findings, “The radiation I couldn’t explain comes from a new chemical element. The element is there and I’ve got to find it. We are sure! I am convinced I am not mistaken!”

A lot of hard work went into extracting this new element and finally, in 1898, they were successful in it. They named the new element Polonium in honour of Marie’s homeland to which she was deeply attached. Although the discovery of Polonium was extremely significant, the Curies were not content with it. They were convinced of their research that pitchblende contained another substance which was thousand times more radioactive than Uranium. But the problem was that this substance existed in such little amounts that it was tough to detect it. The Curies named this substance as radium and this was more stable, radioactive and useful than the other. Thus, the year 1898 became very significant for Marie and Pierre Curie as they discovered two new radioactive elements which contributed to humanity. The research papers written by the Curie couple showed that it was a joint effort. Although they maintained individual laboratory notebooks, yet, whenever they recorded the readings of their experiments they always wrote it as ‘we found’ or ‘we observed’ in their published papers. So it could never be identified as to who did what. In the words of the Curies’, “Certain minerals are very active, from the point of view of the emission of Becquerel rays. In a preceding communication, one of us showed that their activity was even greater than that of uranium or thorium.” No one could make out whether it was Marie Curie or Pierre Curie and this was clearly the intention of the Curies that no one should ever know.

A Proof to the World

“There are sadistic scientists who hurry to hunt down errors instead of establishing the truth.”

---Marie Curie

Marie and Pierre Curie had a tough time proving to the scientific community about the existence of the two new elements. There were many fellow scientists at the university who refused to believe them. In order to convince them that radium and polonium existed, the Curies were determined to isolate the pure elements. For this they would need to buy several tons of ores which they could not afford. Most of their life’s savings were spent on purchasing waste ores. Marie succeeded in arranging tons of industrial waste from the Austrian government which was brought from Bohemia. For the next four years, from 1898 to 1902, Marie Curie and her husband laboured hard in dreadful conditions to melt, purify and treat the pitchblende, to extract small amounts of radioactive materials. They were totally immersed in their work and the entire process was too exhausting for the couple. Normally, it would have taken a team of mine workers to do the job that they were managing among themselves. Marie could not neglect her home and daughter Irene and so it was all the more taxing for her.

Marie’s efforts finally paid off in the year 1902 when she prepared one tenth gram of pure radium and determined its atomic weight as 225.The scientists who had initially doubted her were silenced and radium was officially declared as an existing element. Marie had enough radium now to complete her dissertation.

Marie Curie's Beloved Radium

“We must not forget that when radium was discovered no one knew that it would prove useful in hospitals. The work was one of pure science. And this is a proof that scientific work must not be considered from the point of view of the direct usefulness of it. It must be done for itself, for the beauty of science, and then there is always the chance that a scientific discovery may become like the radium a benefit for humanity.”

---Marie Curie

Radium was the focus of Marie and Pierre’s life and was very precious to them. As they worked on it continuously for four years their health suffered a lot. To earn sufficient money for a living along with their research they worked as teachers at the university. Weighed down by work pressures at home and at the lab, too little food and too much harmful radiation, the health of the Curie couple started weakening. Several tragedies too hit the Curie family. Marie’s father passed away and she lost her little girl due to premature delivery, in the fifth month of her second pregnancy. Her misfortunes did not stop here and her sister Bronya’s son, died of tubular meningitis. As though this was not enough, Pierre fell sick and started complained of acute pain in his legs. Despite the setbacks, Marie continued working hard along with Pierre on their most loved element, radium. She found out that radium caused burns on the skin and destroyed the tissue as Pierre burnt himself while doing some experiments.

It was then that it dawned on them that radium could be helpful in destroying cancerous growths. Thus was born the radium therapy for cancer healing and an altogether new industry, ‘the radium industry’.

Doctorate for the true Philanthropist

"You cannot hope to build a better world without improving the individuals. To that end each of us must work for own improvement and at the same time share a general responsibility for all humanity, our particular duty being to aid those to whom we think we can be most useful".

---Marie Curie

Marie put down the findings on radium in her doctoral thesis and presented it on 25th June, 1903. The examination committee was amazed as no one had ever before made such a scientific contribution in a doctoral thesis. Her years of hard work had finally paid off and she was awarded the coveted doctorate. Marie had sacrificed a lot for this degree. She normally worked over a huge vat outside her laboratory but on rainy days she didn’t have a choice but to work in a cold, damp and drafty lab room. The noxious radon gas had contaminated everything present in the lab. Radon is considered a health hazard due to its radioactivity and it’s an indirect decay product of Uranium or Thorium. Marie was exposed to a unit of radiation per week which was a dangerous amount, yet she did not pay any heed to her health and continued with her study.

Shortly after her doctorate, the Curies made a vital decision. They had discovered the technique to extract radium from spent pitchblende and now a whole new medical market had emerged for this precious element. People from all over the world were desperate to know the way to isolate radium so that they could use it for therapeutic purposes. This was a great opportunity for the Curies; they could either publish their results without charging a penny or they could patent their methods and sell it for a bomb. Patenting would mean that radium usage would be limited and Marie and Pierre would become wealthy. Marie had no confusion, as the well-being of the humanity was her only choice. This decision of hers was a blessing to thousands who were cured due to radium treatment, but it also meant many more years of poverty and working without a proper laboratory for Marie.

Nobel for Marie

“I am one of those who think like Nobel, that humanity will draw more good than evil from new discoveries.”

---Marie Curie

Marie and Pierre’s relationship was the most fulfilling, fruitful and creative partnership in the scientific history. Their name and fame started to spread and they were now recognized by fellow scientists. They got very little support from France but the other countries were more receptive towards them. In 1903, Marie and Pierre got the Davy medal from Lord Kelvin (British mathematical physicist and engineer) and the Royal Society of London. No doubt the Curies felt honoured, but at the same time the poor souls did not know what to do with the medal and gave it to little Irene to play, as though it were a toy. In the same year it was announced that Marie and Pierre Curie would be getting the Nobel Prize for Physics along with Becquerel for their contributions to the theory of radioactivity. Nobel Prize meant not only recognition but also money. Money was a welcome relief as Marie and Pierre could do less teaching and save for their own laboratory. Their health had suffered immensely due to over exertion and poor working conditions. Their finger tips became permanently scarred due to burns and had hardened due to continuous handling of radioactive substances without taking any safety measures. Marie would be tired most of the time and she lost more than 15 pounds of weight. That’s the reason why when the Nobel Prize was announced in December of 1903, they were not well enough to go in person to Stockholm and receive the honours.

The Curies now suddenly found themselves in a midst of public and press attention. They were suddenly surrounded by journalists from all over the world which was an intolerable and unavoidable situation for them. It was a good time for the Curies as Pierre was also offered a position of Professor in the Sorbonne’s research laboratory wherein he could take Marie as his lab superintendent. Pierre and Marie were happy to take the posts but somewhat bitter that France gave them recognition only after they received the Nobel Prize.

New Beginnings and Sad Endings

“Pierre, my Pierre, you are there, calm as a poor wounded man resting in sleep, his head bandaged. Your face is sweet and serene, it is still you, lost in a dream from which you cannot get out.”

---Marie Curie

In 1904, Marie and Pierre were blessed with their second daughter, Eve. The couple loved to work together, as well as enjoyed their family time together. Although most of the days they were busy with their research work and the children were cared for by the servants; but whenever they had time in the evenings or on holidays, they would spend it with their kids. Their marriage was a marriage of two great minds, who were each other’s constant companion till death did them part.

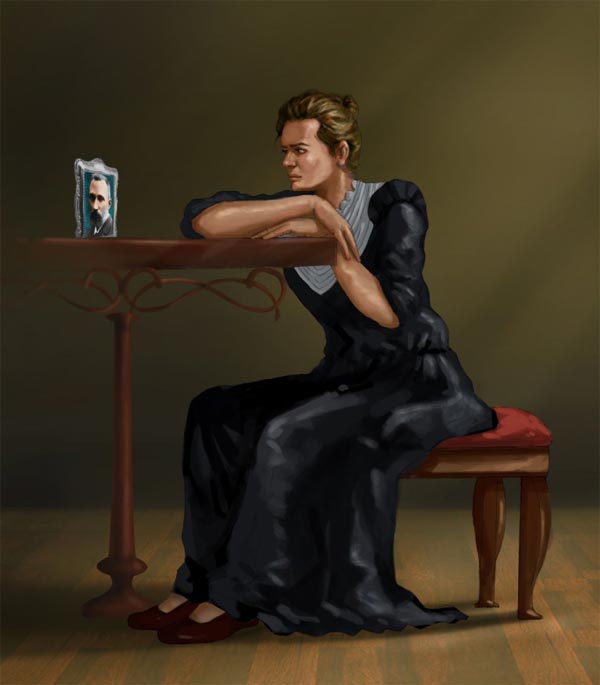

19th April, 1906, was a very unfortunate day for Marie. It was a rainy afternoon and Pierre decided to walk down to his laboratory along the crowded streets of Paris. As usual he was lost in his thoughts and his vision was blocked by his open umbrella when he tried to cross the road. Unconsciously, he walked into the path of a horse drawn carriage and was instantly trampled to death. It was a big shock for Marie as Pierre was not only her husband but also her research partner and a constant companion. The grief was so immense that she could never recover from it. She dressed in black and would keep to herself. She could not believe that Pierre was no more and would often say, “Pierre is dead? Dead? Absolutely dead? ” After Pierre’s death the university appointed Marie as the professor of Physics. She was the first woman in France to hold this distinguished position. Marie strived hard to do her scientific work as well as balance her time at home so that her daughters were not ignored.

Marching Alone

“My Pierre, I got up after having slept rather well, relatively calm. That was only a quarter of an hour ago, and now I want to howl again – like a wild beast.”

---Marie Pierre (May 1906)

It was 5th November, 1906, a historic day in the life of France and as well as for Marie Curie. At 1:30 pm Marie became the first woman to deliver a lecture at Sorbonne, the greatest University of France. Her lecture had started exactly where Pierre had left off months before. Marie spoke with confidence and authority on radioactivity. Life had been hard on her but she surged ahead with her head held high, taking up all the challenges coming her way and emerging a winner. Now that she was alone it was difficult for her to single-handedly manage outside work and take care of her daughters. Luckily, Pierre’s father still lived with them and helped Marie in bringing up the girls.

Marie kept on working with her favourite elements Radium and Polonium. In order to fully understand the chemical character of radium she worked on to separating it to get its pure form. As Curietheraphy was fast catching on as a treatment for cancer, Marie researched on ways to measure the minute amounts of radium so that the exact dose needed for treatment could be calculated.

Marie suffered another blow when Pierre’s father, who was a major support system, left for the heavenly abode. Her daughters were very close to their grandfather and it was very shocking to them. Marie made arrangements for a young Polish woman to stay with them as the children’s governess. As Marie had no faith in the French school system she organized a private school for her daughters where the parents themselves were the teachers. It was a group of ten children who were taught in their own homes by the parents who were eminent professors.

The Second Noble for Madam Curie

“Nothing in life is to be feared, it is only to be understood. Now is the time to understand more, so that we may fear less.”

---Marie Curie

1911 wasn’t a good year for Marie. Her name was tarnished when her relationship with physicist Paul Langevin became public. Paul, who was five years younger to Marie, was a former student of Pierre. Though he was already estranged from his wife, yet, Marie was accused of destroying his marriage. Due to all this negative publicity and smear campaigns, the Academy of sciences refused her entry as a member. This whole episode deeply hurt Marie. However, in December 1911, the Swedish Academy of Sciences recognized the brilliant work done by Marie and awarded her the Noble Prize in Chemistry. To be honoured with one Noble prize in a lifetime was an unachievable dream come true, but to get two, was unbelievable. But a simple Polish woman from a humble background had accomplished this feat.

After three years of getting the second Noble prize, an institute of radium was started in Paris in the year 1914. It was called the Pavillon Curie and Marie’s wish to have a laboratory was finally fulfilled. Sadly, she didn’t have Pierre to share the joys with her.

Marie’s health soon started failing and she had a major kidney surgery done which took a long time to heal. Thankfully, she had a good set of friends along with her daughters who helped her recuperate better. Albert Einstein, the renowned physicist and his son were Marie’s good friends and she spent hours with them discussing scientific ideas. Following words depict what Albert Einstein thought about Marie:

“It was my good fortune to be linked with Mme. Curie through twenty years of sublime and unclouded friendship. I came to admire her human grandeur to an ever growing degree. Her strength, her purity of will, her austerity toward herself, her objectivity, her incorruptible judgement— all these were of a kind seldom found joined in a single individual... The greatest scientific deed of her life—proving the existence of radioactive elements and isolating them—owes its accomplishment not merely to bold intuition but to a devotion and tenacity in execution under the most extreme hardships imaginable, such as the history of experimental science has not often witnessed.”

Violence and Gloom

Marie’s health had now improved considerably and she had less to worry as the girls had grown up. Irene was 17 and Eve had turned 10. Her research work was progressing very well and she had even rented a villa in Brittany to spend the summers. Things had got better for Marie but the clouds of World War One were gradually darkening on the horizon and eventually the war broke out. Marie had studied about X - rays in detail and she knew that it could prove helpful in treating the wounded soldiers. It would aid in finding hidden bullets and pieces of shrapnel stuck in the body. So Marie, along with Irene, volunteered to x-ray the wounded and for that they headed straight to the front. They went to several hospitals in France and Belgium, trained X- ray technicians and supervised millions of X- rays. Marie’s good work for the humanity did not stop here and in 1916 she trained women to become radiological assistants by starting courses in the Radium Institute. In her endeavour she was aided by Irene who was then studying in Sorbonne. Marie was especially kind to the younger scientists and gave them space in her lab to continue the work on atomic research started by her. In order to encourage talented women physicist like Ellen Gleditsch, May Leslie etc. She hired them as well. She was sympathetic to women who had suffered discrimination at the hands of the male scientists.

A Favour from Across the MIles

“My timidity exceeded her own. I had been a trained interrogator for twenty years, but I could not ask a single question of this gentle woman...I tried to explain that American women were interested in her great work and found myself apologising for intruding on her precious time...” Mrs Meloney

Winning two Noble Prize gave Marie sufficient money to survive and work without any worries. But her concern for the humanity could not stop her from spending it on the war and helping the French. So she was once again empty handed with no means to fund the research work. She did not know that help was not very far. Mrs William Brown Meloney was an editor of a famous New York magazine and had wanted to meet Marie Curie for ages. When they finally met she was surprised that Marie’s laboratory had no equipments and just one gram of radium which was used exclusively for cancer treatment. Mrs. Meloney realized that to continue her research Marie required a gram of radium but she did not have a hundred thousand dollars to buy it. Mrs. Meloney went back to America overawed by Marie and was determined to sort out Marie’s problem with the support of American women. The Marie Curie radium fund was raised in a year and Marie was invited to America by Mrs. Meloney. At the age of 54, Marie along with her daughters set out for the longest journey of her life. Marie Curie received a gram of radium from Warren G, Harding, the President of United States himself in the year 1921.

Hazards to Health

Marie’s trip to America was a huge success, albeit it took a toll on her fragile health. When she was young she had eaten poorly and had exposed herself to radiations without taking any precautions. She had handled radium with bare hands and unprotected eyes even though she knew it caused burns. Other workers had now started using gloves and eye shades but Marie would not let anything stand between her and her beloved radium.

Marie and her daughter Irene worked together as Marie and Pierre did in the early years. The mother and daughter enjoyed working together and they were the only mother-daughter team of physicists in the history of science. Irene married a young physicist called Frederick Joliot who started working with Marie and Irene in the year 1926. This couple spent a lifetime together in doing physics research work, much like Marie and Pierre Curie.

With the passage of time, as age caught on Marie, she paid the price of her negligence to health. In 1923 her vision started getting blurred due to cataract and she was almost blinded. She had to undergo surgery, after which her eyesight was restored to some extent. But the damage done to her internal organs was so immense that it could never be healed. She was suffering from tinnitus which is a constant ringing in the ears and radiation poisoning which gave her severe pains. Despite her health problems she made two trips to America to collect funds for her radium research. The last of her trip was in 1932. In 1934 she went to her laboratory for the last time. She felt extremely unwell and returned back, never to go again. She was weak and tired and down with high fever. Doctors could not help alleviate her pain. Marie was taken to a sanatorium in the mountains accompanied by her younger daughter Eve. She was devoted to her mother and tried to nurse her back to health but Marie’s white and red blood cells plummeted. On the dawn of 4th July, 1934, Marie breathed her last never to see the sunrise in Sallanches, Savoy. The doctors said that the cause of death was ‘aplastic pernicious anemia’ and the bone marrow did not function because of prolonged exposure to harmful radiations. Marie died at a relatively young age of 67 and was buried with her loving husband in the family tomb at Sceaux. Sadly, Marie’s beloved radium was also the cause of her death.

Irene and Fredrick Joliet-Curie kept the legacy alive and formed another close knit husband and wife team. The duo won the Noble prize in Chemistry in 1935, a year after Marie’s death, for their discovery of artificial radioactivity. Marie was a remarkable woman of strength and determination. She gave a great deal to life and took back very little. She was the first ever woman scientist who got the honour of being the ‘Mother of Modern Physics’. Marie left the world but the work started by her still goes on, benefiting the humankind, as Marie had always hoped for.

“Even now, after twenty-five years of intensive research, we feel there is a great deal still to be done. We have made many discoveries. Pierre Curie and the suggestions we have found in his notes, and his thoughts he expressed to me have helped to guide us to them. But no one of us can do much. Yet, each of us, perhaps, can catch some gleam of knowledge which, modest and insufficient of itself, may add to man's dream of truth. It is by these small candles in our darkness that we see before us, little by little, the dim outline of that great plan that shapes the universe. And I am among those who think that for this reason, science has great beauty and, with its great spiritual strength, will in time cleanse this world of its evils, its ignorance, its poverty, diseases, wars, and heartaches. Look for the clear light of truth. Look for unknown, new roads. Even when man's sight is keen farther than now, divine wonder will never fail him. Every age has its own dreams. Leave, then, the dreams of yesterday. Youth, take the torch of knowledge and build the palace of the future.”

---Marie Curie

Biography of Marie Curie | 3 Comments >>

3 --Comments

I am so grateful for your post.Thanks Again.

Good job

Leave Comment.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked.

Greetings! Really beneficial guidance on this informative article!