Photocopier

Edison said discontent is the first necessity to progress. But then, being discontent isn’t enough, the world is full of it. The ones who converted discontent into necessity and have worked in that direction are the ones we call leaders, inventors and outliers.

History is fraught with stories of Edison-like discontent. Did you know that Konrad Zuse the inventor of the world’s first commercial computer, hated calculations. He found them tiresome. It was this discontent that set him out on the path to build a calculating device which later came to be known as a computer.

Inventions, and the stories behind them, have always been interesting. If you look back in time, you will find that with the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, mankind has witnessed some amazing inventions. Inventions that have changed the way we live.

James Watt, a famous Scottish inventor and mechanical engineer is said to have lived during the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, that is the early 1700s.

Although Watt is popularly known for his contribution to the invention of the steam engine, only few know that Watt also developed the concept of horsepower and watt. These concepts are units to measure the rate at which work is done.

Watt was a busy inventor; he belonged to the milieu of the Industrial Revolution. It was his improvements to British inventor, Thomas Newcomen’s engine that worked wonders.

It so happened, that Britain was going through a major industrial boom, as a result, she was in need of significant quantities of raw material including coal.

Apparently, the coalmines in Devon were prone to flooding and the only way to tackle the situation was by deploying Newcomen’s engine, which was a steam pump.

Ideally a steam pump was used to pump water out of the mine, but considering the damage the flood was doing, the pump wasn’t fast enough. Watt studied the working of the pump, improvised it and bingo. He turned the pump into a steam engine. It was powerful enough to drain the mines.

In those days, Watt lived in proximity to many of the mines in Redruth, Cornwall. With the success of the steam engine, Watt got into manufacturing engines. Side by side, he was also involved in other experiments and inventions. This resulted in increased paperwork.

He was discontent with the mounting paperwork that took much of his time. He told his friend, he was finding it difficult to manage clerical works and his attempt to find an intelligent clerk was fruitless.

Only three centuries had passed since the invention of the printing press, which was invented in 1450. And there wasn’t any method of making several copies existing then.

In some cases, people adopted a mechanical method that used linked multiple pens.

Finally, in 1780 Watt developed the first method of making copies. In the beginning it seemed preposterous. He tried to physically transfer some ink from the original to another sheet of paper.

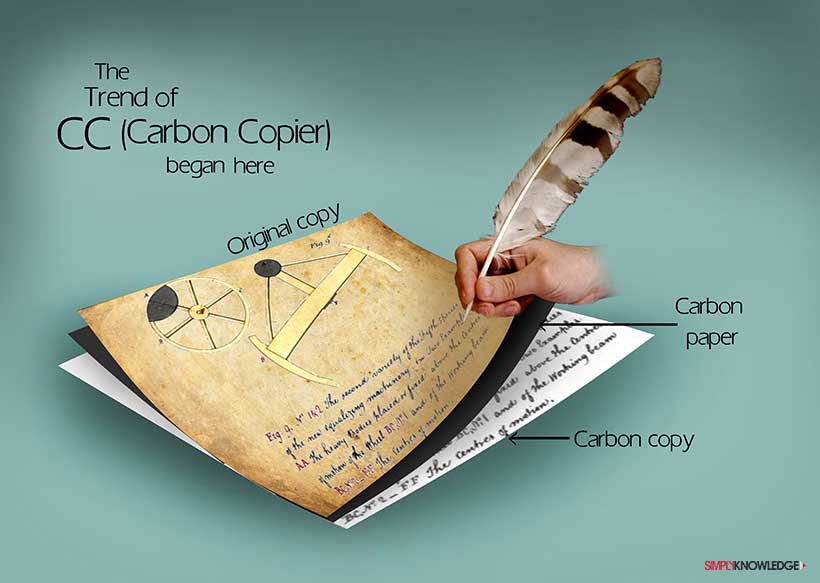

How is that possible? Well only if you use a thin sheet of paper and place it on another sheet of paper and start writing. Once the nib is pressed against the paper, the ink will easily leave a print on the paper placed under it.

Wait up! Watt knew he was close to inventing something interesting. After several experiments, he formulated an ink, made out of gum Arabic and carbon black. He selected a special thin paper and inked one side of it. So that while writing on it, it would leave print on the paper under it and thus create a copy.

The black print copy of the original came to known as carbon copy or cc. Although carbon papers have become redundant, the term cc is still used by most of us on a daily basis. Remember? Your boss asking you to send him a cc of the email you would send to the client.

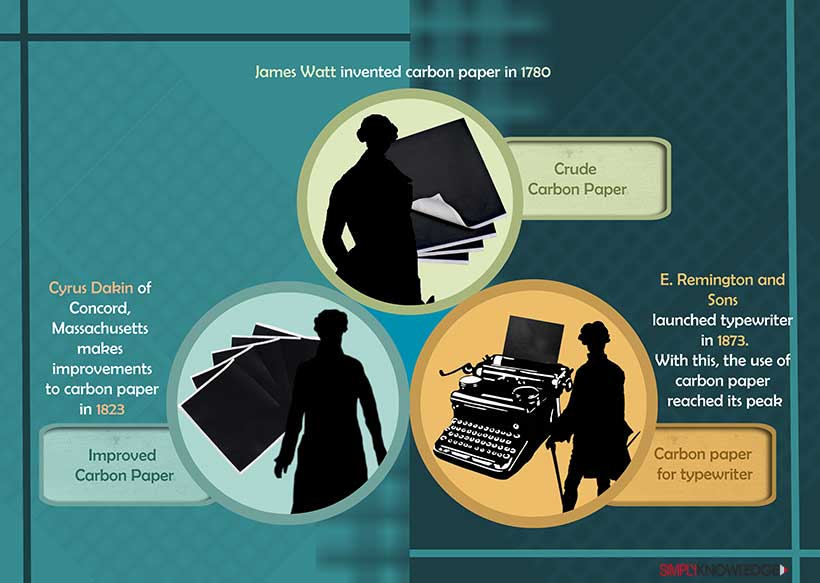

In the beginning, some banks thought this invention could lead to forgeries. Like most inventions, carbon paper got better and gradually found acceptance.

It took about 100 years for making a copy using carbon paper popular. Watt invented this paper in 1780. Add another fifty years to it and you have Cyrus Dakin of Concord, Massachusetts make improvements to it in 1823.

Fifty years later, in 1873 when E. Remington and Sons, manufacturers of firearms and typewriters launched the typewriter, the use of carbon paper reached its peak in popularity.

For at least another 100 years, using carbon paper to duplicate the original document became a popular photocopying process. It was widely used in trade as counter receipts and invoices.

Until the late 18th century, the practise was that the offices employed copyists, scribes and scriveners to duplicate the copy of an outgoing letter.

What they would do is – they would write out the copy by hand. This practise continued for most of the 19th century.

Even before the carbon paper was invented, there existed different duplication processes that were used for different purposes.

Like Mark Twain in early 1870s wrote some of his stories on the Manifold Writers. It was said the Writer could be used to make up to ten copies.

The thing about an Invention is how far can you take it? And what more can you get out of it?

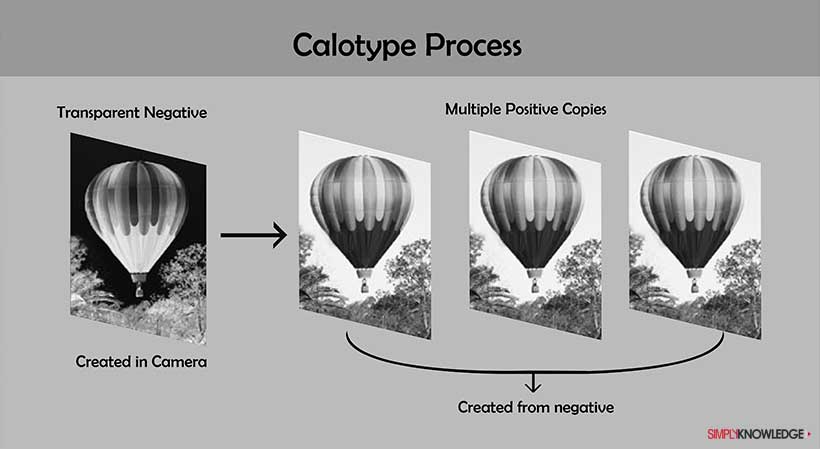

In the mid-19th century, the invention of the camera was in its nascent stage. It was the invention of William Henry Talbot’. Calotype Process that gave a great impetus to photographic printing.

The process introduced the negative-positive process of a picture which enabled making multiple copies of the original.

In a way, it was similar to making photo copies, but not the copier way. Well, the story of the Calotype process dated back to the early 1840s. No doubt, the process underwent a series of developments.

As time passed, means of communications increased. More and more businesses began corresponding across boundaries and continents. Trade and commerce called for increased paperwork and as a result there was a need to copy documents that were received by an office.

The earliest effort in this direction was found in Europe, in the form of the development of photosensitive paper. In the late 19th century, the blue process technology was used to make copies of architectural and similar drawings. The technology was developed on the basis of the cyanotype process (a photographic printing process that gives a cyan-blue print).

Under the Blue Process also known as Blueprinting, a junior draftsman copies the original drawing onto a translucent paper with black India ink.

He then puts the translucent paper on a sheet of photosensitive paper in the tray of the blue printing frame.

After that he covers the frame with a heavy glass plate so that the papers remain pressed together. The frame is then kept out in the open, exposed to sunlight for almost an hour.

When he slowly opens the frame. Ta-Da! Magic! He will find the photosensitive paper in complete blue, except for the tracing; it leaves white lines. So what he will have is a fine blueprint of the original plan or drawing.

The flipside of this process was that it was time consuming and wasn’t suitable for duplication of office correspondences and documents.

In 1906, The Rectigraph Co., an American establishment, developed camera-based photocopying machines.

No Invention is a dot, but a collection of dots that makes a point. A little later, the Rectigraph together with Photostat Corp, a company affiliated to Eastman Kodak developed the Rectigraph and Photostat machines, during 1907-11. These machines consisted of a large camera and a developing machine. It used sensitized paper which was as long as 350-foot rolls.

The minute the picture of the original is clicked, the prints are made directly on sensitized paper. There are no negative, plate or film intervening procedures involved. The picture is given a minimum exposure of ten seconds after which the picture is cut off from the roll and is then taken to the developing bath. In a matter of 35 seconds, the copy of the original is almost ready.

But once the copy is dried, you will see the first print of the original in an inverted form, i.e. the text takes the colour white and the page black.

Obviously, this is not what we need. What we need is a white page with black fonts.

We are just one step away from getting what we want. Now that we have the first print which looks like this –

Click a picture of this print and on to the sensitized paper you would get its print in black text and white background. That’s it! You can now make as many copies as you require.

The Rectigraph machines were popular with insurance companies and abstract and title companies.

The Photostat machines were acquired by DuPont Co. in 1912, while the Rectigraphs by the Haloid Co. in 1935. The Rectigraphs were still sold in the early 1960s.

Even as copier makers were trying different ways to make copies. Companies like Apeco, 3M and Kodak sold desktop reflex copying machines. These machines were improved version of the Blue process printing.

Chester Carlton, the man who invented the photocopier, graduated in Physics from the California Institute of Technology at a time when the country was facing the Great Depression in 1930.

Young Chester was the breadwinner of his family since the age of fourteen. His dad had developed crippling arthritis and he lost his mother when he was seventeen.

With a debt of $1,400, finding a job to pay off the debt in the times of Depression just wasn’t easy. However, he did find a job at the Bell Laboratories in New York. He worked there as a research engineer for just $35 per week.

The depression deepened, as a result in the layoffs called out at Bell, Chester lost his job. It was his next job that turned things around.

He joined an electronic firm ,P.R. Mallory which was well known for its batteries. At Mallorys, he worked his way up and was promoted to manager of its patent department.

His job called for making copies of patents. Unfortunately at that point in time, there were only two ways of making copies; either get it photographed or laboriously write new ones.

Apparently, either of the options was expensive and time consuming. The thing about Monotony is that it irks the genius and the sluggards. With the kind of setting Chester came from he was no sluggard. He headed straight to the Google of his time, the New York Public Library. He went through tons of scientific articles and articles relating to photography.

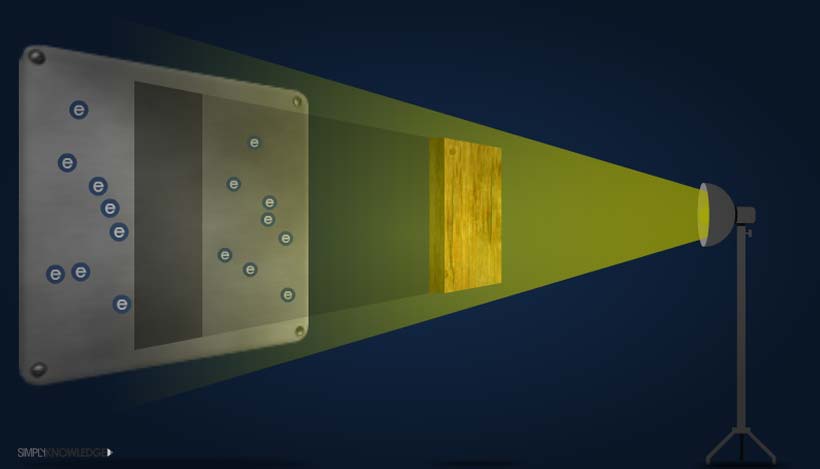

His on the job experience taught him that the photography way of copying was a wet and messy process. During his research he learnt of photoconductivity, that is when light strikes the surface of certain materials such as silicon, germanium, lead sulphide and a few more, the conductivity (flow of electron) of the material increases.

One thing was for certain, conduction is the process by which heat or electric current moves through from one substance to another. With little understanding of photoconductivity, Chester felt the tail of the Giant idea. But then an idea is just one percent of the invention, it is 99 percent of hard work that makes the idea a reality.

What if we project the image of an original photograph or document on a photoconductive surface.

The print areas would appear dark, as a result it will not allow current to flow. The non-print areas would light up the photoconductive surface.

Chester began carrying out experiments in his kitchen and was working on the concept he termed “electrophotography.” Being a patent lawyer himself, he knew this was no ordinary concept, so he applied for the patent in October 1937.

Here Carlson’s wife was getting weary with his endless experiments, and made him move his laboratory elsewhere. So he moved it to a room in the back of a beauty salon owned by his mother-in-law, in Astoria.

During this time, Carlson was keeping low on health, so he hired a German physicist named Otto Kornei to assist him in his pursuit.

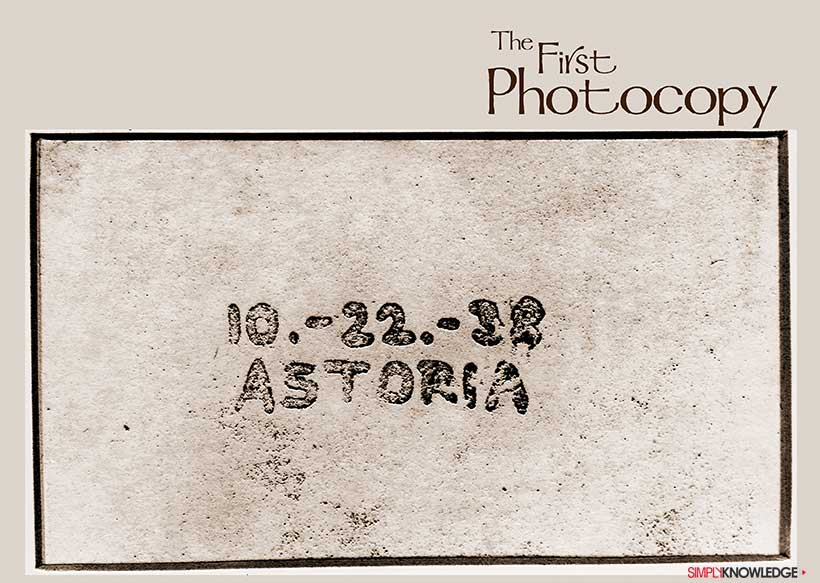

It so happened that one day Otto took a zinc plate and coated it with a batch of freshly prepared yellow powder, sulphur. Carlson rubbed the sulphur with a handkerchief to give an electrostatic charge.

He then placed a transparent microscope slide on it, on which he had written the words “10-22-38 Astoria” in India ink. Soon after this, they drew the curtains and darkened the room and placed the slide under a bright incandescent lamp for a few seconds.

The slide is removed quickly and the sulphur surface is covered with lycopodium powder. This may seem like magic; now with a gentle breath, in the manner you blow off the birthday candles, blow off the lycopodium powder of the sulphur surface and what we have is the almost exact image printed on the glass slide that reads - “10-22-38 Astoria.”

Was this by fluke or magic? So to convince themselves the duo repeated the experiment a couple of times and found it was for real.

The next thing was to preserve the image. How do we do that? The powder images were transferred on to wax paper, after which the sheets were heated so as to allow the wax to peel away. And what you are left with is a copy of the original.

It may seem to be a complicated and lengthy process compared to the copiers of the current times, but that’s how technologies develop.

Carlson’s first xerographic apparatus did not work well, but it did lay a base for an electro photographic method of photocopying.

The entire idea of electrophotography was still to be worked upon, but the research required money and Carlson didn’t have any. It is said that between 1939 and 1944, he approached many big names in the business including IBM, Kodak, General Electric, RCA and the like, but was turned down.

All this while he did not disassociate from the Mallorys, in fact, it was through the Mallorys that he got in touch with a non-profit organisation that invested in technological research – the Battelle Memorial Institute.

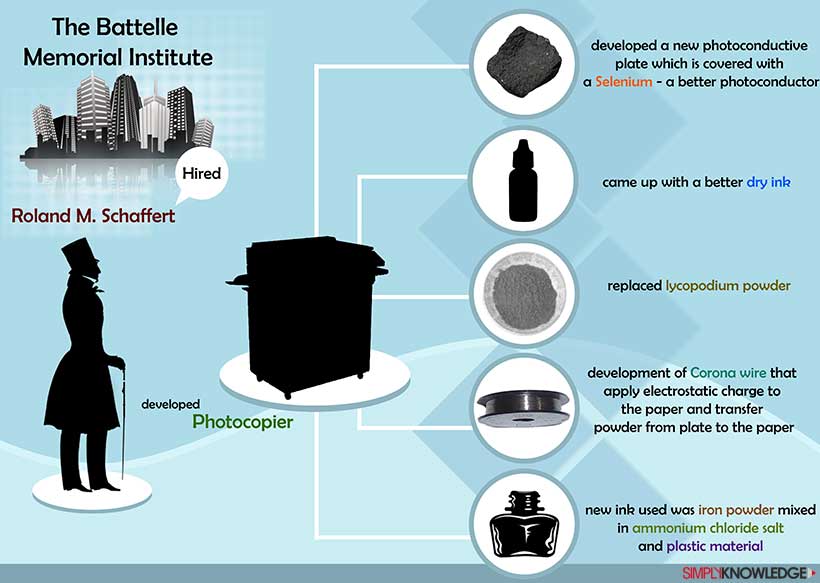

Battelle assigned the project to a research physicist and a former printer – Robert M. Schaffert. He started off single headedly, but was later provided with assistants and within a year’s time, he made improvements to the technology.

To begin with, the team at Battelle developed a new photo conductive plate. The plate was covered with a photoconductive material – selenium, which happened to be a better photoconductor.

Robert came up with ☑ a better dry ink. He also replaced ☑ lycopodium powder and other materials as they produced a somewhat blurry image.

But it was the development of ☑ the corna wire that took the xerographic apparatus a notch up.

Corona wire could do two things:

- apply electrostatic charge to the plate

- transfer powder from plate to the paper

The new ink was iron powder mixed in ammonium chloride salt and plastic material.

As the ammonium chloride salt was electro conductive, it worked great on the projection of the image. The areas where there was low charge or no image, the iron particle stuck to the salt and not to the plate. Besides it left a clearer copy than the earlier process.

Coming to the plastic material, it was designed to melt when heated and fuse the iron particles to the paper. This material was called the toner. In the beginning, the makers developed few colour tones to produce full colour copies.

What Carlson started in 1939, the scientists at the Battelle Memorial Institute finally developed into an extraordinary invention – a photocopier.

Scientists at Battelle were almost ready with their electrophotographic machine. In Jan 1947, Battelle signed a licensing agreement with a company located in Rochester, New York known as Haloid.

The Haloid Company, established in 1906, manufactured photographic paper and later got into other photographic products. Around that time, in 1947, it was looking for a new technology to develop photocopies.

Haloid studied Carlson’s technology of making copies; the electro-photographic way. Initially, the Haloids found the process complicated and tried to consult experts.

Carlson named the electrophotographic process of making copies – Xerography; it is Greek for dry writing. After an assessment of the technology, Haloid learned the machine requires more research and investment.

Ideally, it should have been named Xero machines, but in order to match similarity with the then famous brand Kodak, the letter x was added to Xero.

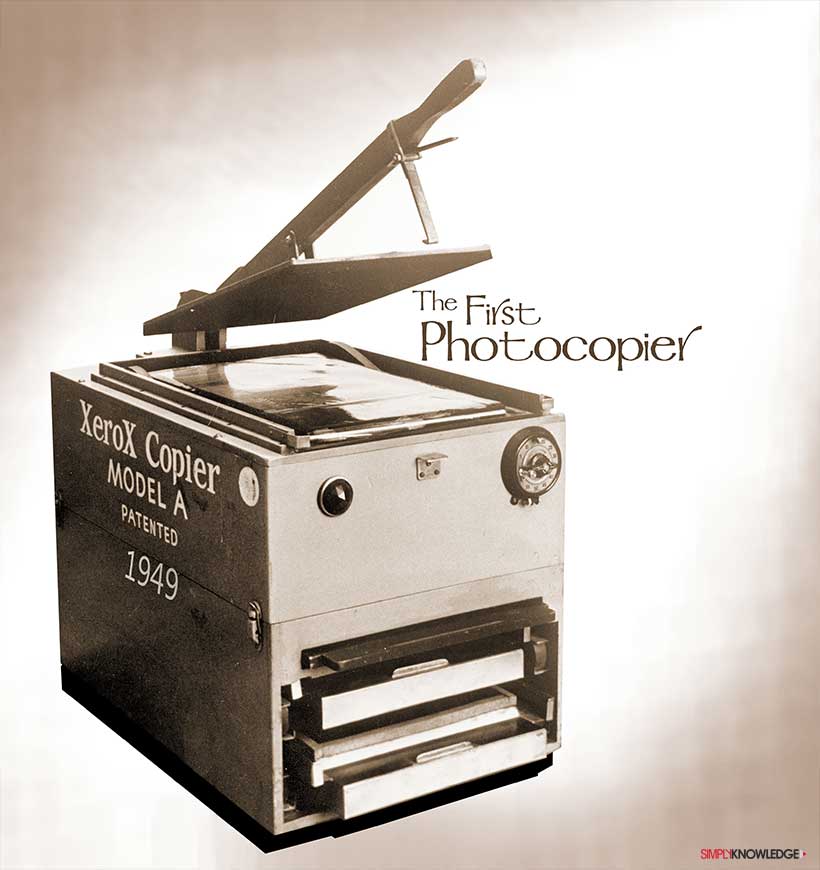

With about an investment of $25,000 per year and almost two years of research, Haloid introduced the first photocopiers in 1949 and they called it the Xerox machines. The first Xerox copier machine was named the Model A in 1949. However, the Xerox machines weren’t popular until 1961, when Model 914 was introduced. The models to follow Model 914 made Xerox so popular that photocopying of the original was eponymously called Xerox.

Performance wise the entire processof Model A wasn’t as efficient as expected. It took 45 seconds to make a single copy and at the most could make around a dozen copies in one go.

The reason the process was time taking was because of the flat plates. As it involved manual labour in setting up the flat beds. In the copiers to follow, the plates were replaced by rotating drums. With time, better technologies began to produce a better photocopier.

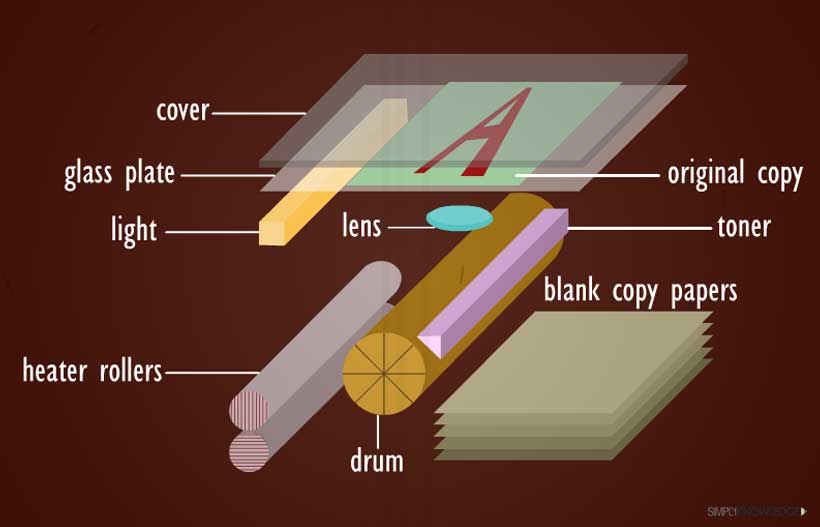

Xerography also known as electrophotography basically is a combination of two technologies – electrostatic printing and photography.

The process follows three basic steps and produces a copy of the original in seconds.

Step One:

When you place a document in a copier, a bright light is passed over the paper.

This light passing is done in an arrangement. The source of the light is between the lens and the drum. The light is passed through a lens and on to a specially coated drum at the same time.

The light passing step gets the drum charged electrostatically; as a result you have the mirror image of the document on to the drum.

Step Two:

The toner is attracted to the area that is electrostatically charged. As a result, fine black particles that make up the ink are attracted to that area.

Step Three:

As the drum rotates the same area gets printed on to the paper. And Ta-Da! You have a copy.

So all it takes is the light to charge the drum, the drum gets the image imprinted on to it. The toner gets attracted to the electrostatically charged area and leaves ink accordingly.

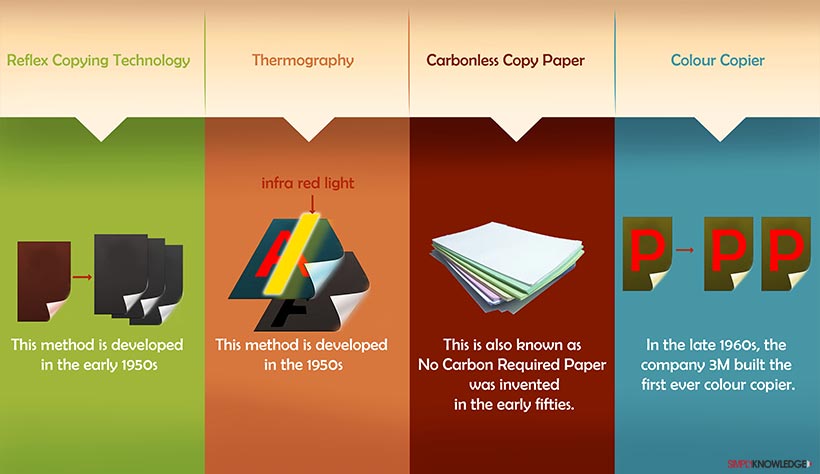

In the early 1950s among other photocopying methods developed was the reflex copying technology. In this method, the original to be copied is placed face-up and is covered with a sheet of translucent paper with heat-sensitive coating on it.

After this, infrared light is passed over the translucent paper. While doing so the white portion of the original is reflected on to the translucent paper and the black portion absorbs the light. The light that was absorbed by the black portions heats relevant portions of the heat-sensitive coating on the copying paper. And thus you finally have a copy.

Around the same time, another photocopying method was developed called Thermography. In this process, the sensitized copy paper is placed in contact with the original and is exposed to the heat of infra red light. In doing so, the image gets transferred on to the special copy paper.

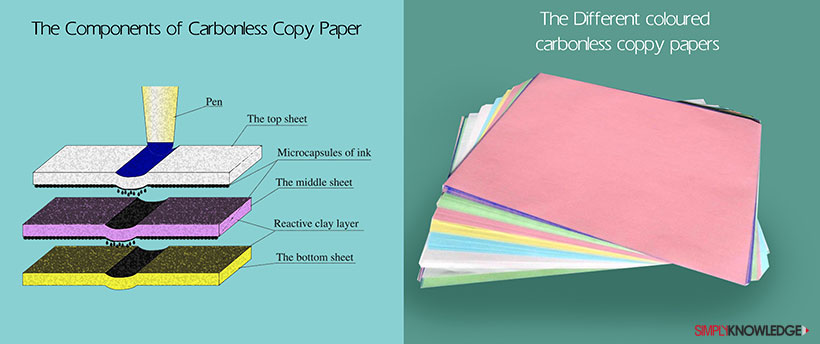

Carbonless copy paper also known as No Carbon Required paper was invented in the early fifties. The idea was to have a biodegradable and stain-free alternative to carbon paper. The carbonless copy paper is made of sheets coated with micro-encapsulated dye or ink and a layer of reactive clay.

The idea wasn’t an instant hit. The use of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in making these papers raised a major concern over health and environmental issues. The PCBs are said to be highly toxic and as a result it was banned.

In the meantime, in the late 1960s the company 3M built the first ever colour copier. Unlike the regular electrostatic technology, it used the dye sublimation process. This process uses heat to transfer dye onto the material on which the copy has to be printed, say paper, plastic card or fabric.

This technology was found to be of great utility in developing counterfeiting currency and security related items like printing holograms, watermarks and micro printing.

Canon was the first company to launch the first ever electrostatic colour copier in 1973.

By 1970s, digital technology was touching almost all the domains of electronics. It was during this time, all technologies that were built based on analogue signals; that are machines that depended on changes in phenomena such as sound, light, temperature, or pressure, were now run on digital signals. These signals were received on processing binary values.

The research laboratory of Xerox popularly known as Xerox Palo Alto Research Center developed the foundational technology for laser printers in the early 1970s. The Xerox 9700 Electronic Printing System released in 1977 was the first laser printer product. The machine could copy, scan and print copies.

A laser printer was a combination of two technologies; laser and electrophotography. It operated at speeds of more than 100 impressions per minute.

In the early 1990s, the market was flooded with companies like IBM, Canon, Epson and HP. Hewlett-Packard came up with a fine product line of laser printers; in 1992 the LaserJet 4 was a popular printer in the office circuit.

Technologies kept developing and printers got better and better.

The Carbonless copy paper invented in fifties was banned for almost fifty years. Come year 2K, fresh reviews were made of the latest manufactured carbonless paper. It was found to be safe to use.

Companies that met the norms of industrial hygiene and work practise could use carbonless copy paper. This review resulted into the increased use of carbonless paper.

The carbonless copy paper is available in an array of colours such as white, yellow, pink, green, and blue. In most cases the white copier was placed on the top and the other coloured were layered in the following sheets.

Yes sure you can, in fact today you have your ATM receipts, credit card receipts, teller generated receipts and check books printed on a carbonless copy paper.

Photocopying has come a long way from being the first of its kind to the state-of-the-art, from one copy in 45 seconds to 22 copies per minute. The current lot of printers or copiers also have optional digital scanners and fax capabilities.

Word of Caution: Ventilation. As photocopiers generate heat and hazardous gases make sure the room is well ventilated.

Pablo Picasso said “a good artist copies, a great artist steals.” Considering the kind of copiers around one can say, “a good copier copies, a great copier copies, faxes, scans and prints.”