Introduction

“I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free”

These immortal words of Michelangelo have echoed down the centuries and still not lost an iota of their charm. Never in the history of the Western world has there been as multi-faceted a figure as that of Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, popularly known as Michelangelo. He burst upon the artistic horizon of fifteenth century Italy, the period popularly known as the Renaissance or rebirth of Western culture, a period of progress and change in Europe, as it emerged from the dark ages of the previous century. Along with Leonardo da Vinci, his compatriot, Michelangelo was known as the Renaissance Man, while he was yet alive. He proved to the world, even as a young artist, that his formidable talents in sculpture, painting, architecture and to an extent, poetry could not be replicated. His style in architecture was Mannerist in general, a style followed by many artists during the Renaissance, based on the ancient Greek and Roman manner. He often used perspective or depth in painting to lend a three dimensional appearance to it. His most famous sculpted figures include the Pieta, a depiction of the Virgin Mary with the body of her son, and David, the Biblical figure who killed the giant Goliath.

It was 6th March, 1475, in Caprese, Tuscany. Lodovico Buonarroti waited anxiously for the horoscope of his 6th child, a son. As the astrologers finished their calculations and came to a decision, it was clear from their expressions that they were in the presence of an awe inspiring new personage. Indeed, Michelangelo was born under auspicious stars, and as was habitual during that period, astrologers predicted that he would attain great stature in the world – a prediction that proved to be completely accurate.

A few months later, the family returned to Arezzo, Florence, which was their native place and settled on the outskirts where Lodovico had a farm and a marble quarry. Michelangelo could not be nursed by his mother Francesca di Neri Del Miniato di Siena because of her illness and was therefore sent to a wet nurse who lived near the quarry. When he was much older, he famously commented to his biographer, “Giorgio, if I have anything of the good in my brain, it has come from my being born in the pure air of your country of Arezzo, even as I also sucked in with my nurse’s milk the chisels and hammer with which I make my figures.” His mother remained ill most of the time and by the time little Michelangelo was six years old, she had passed away.

Michelangelo was a lonely and quiet child, especially so as he did not have a mother to pamper or encourage him. He was the youngest in a large household that was by no means well-off. His father, Lodovico, was unable to make both ends meet, so the little Michelangelo spent a lot of time brooding. This tendency remained with him all throughout his life, and he made very few friends. Arrogant and rude behaviour was the shield behind which he hid his sensitivity and vulnerability. Under financial strain, Lodovico sent his sons to the ‘Guild of Wool and Silk’ to be apprenticed. Michelangelo was sent to be educated with the famous humanist Francesco da Urbino. But the poor father was at his wits end, as young Michelangelo refused to learn anything at all. He spent all his time sketching and painting.

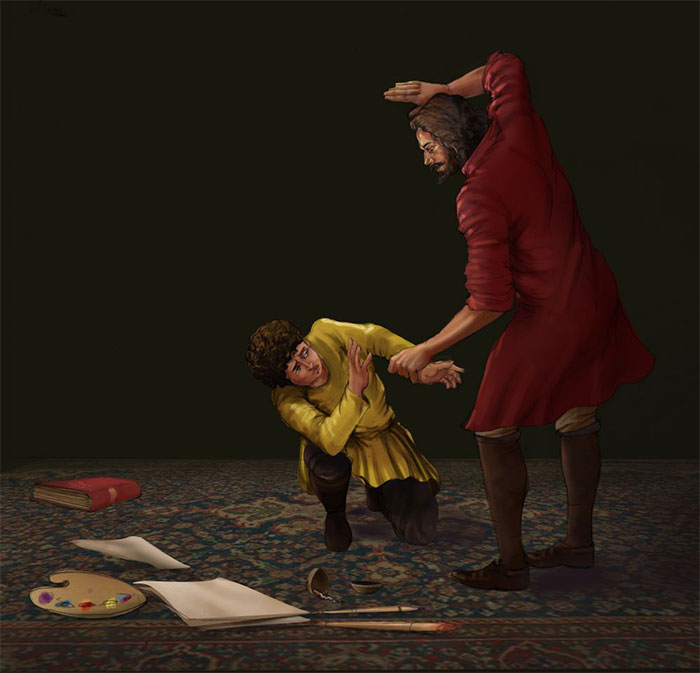

Michelangelo was scolded and even beaten by his family members, but to no avail! Back he would go to his painting, copying all kinds of images. At this time, he met Granacci, who became a lifelong friend and a well-known painter in his own right. Granacci would often smuggle in pictures made by his teacher Domenico Ghirlandajo, the famous painter, and let Michelangelo copy them. Ultimately, Lodovico realized that his son could not be kept away from his obsession and enrolled him in the school of Ghirlandajo, the painter renowned in the whole of Italy.

It is essential to explain Michelangelo’s circumstances whilst he blossomed as the foremost artist of Italy. Florence, the city where he lived and grew, was unofficially ruled by the wealthy Medici family even before the birth of Michelangelo. To quote from Antony Mason, the author of In The Time of Michelangelo, “Italy was divided into a large number of small states which were usually ruled by a major city such as Florence…governed by wealthy powerful families…Keen to display their good taste and wealth, as well as their power, the Medicis became important patrons of the arts…” The Medici family was the founder of the first bank in Europe, the Medici Bank, in the fifteenth century. The family gave Italy four Popes; Europe, two queens and several able administrators to Florence, continuing to dominate the political and economic scene in Florence and Tuscany till 1737. Thereafter, the family went into oblivion due to ongoing financial and other troubles. Michelangelo was fortunate to be born when one of the greatest of the Medici, Lorenzo the Magnificent was at the peak of his career. One of the ablest and most generous of the Medicis, he was a proficient administrator and a caring father.

It was in 1488 that Michelangelo was apprenticed with Domenico Ghirlandajo, at the age of 14. It is worth mentioning that Michelangelo was one of the few eminent personages whose biography was written during their lifetime. Michelangelo’s biographer was the well-known artist and sculptor, Giorgio Vasari, whose book, ‘Life of the Most Excellent Painters, Artists and Sculptors’ contains a detailed account of Michelangelo’s life and works. Vasari writes, “When the ability as well as the person of Michelangelo had grown in such a manner, that Domenico, seeing him execute some works beyond the scope of a boy, was astonished, since it seemed to him that he not only surpassed the other disciples, of whom he had a great number, but very often equalled the things done by himself as master.”

Thus, very early during his apprenticeship, Domenico knew that he had an unusually talented disciple with him. The first episode of many that established Michelangelo’s superiority was, when a German artist named Martin became popular in Italy. One of his works, St. Paul being attacked by demons, fell in the hands of Michelangelo. This ‘brass relief’, the latter copied on paper and for colour and effect, added the scales of colourful fish and many bizarre demons. This drawing on paper was so impressive that he became famous in and around Florence. The effect this action had on his future was a defining one, for he soon found himself in the midst of an unexpected turn of destiny.

News of his talent travelled to the Medici palace and soon he was invited into the presence of Lorenzo the Magnificent who invited him to join his group of sculptors in his own garden in 1489. He learnt sculpture from the famous Italian sculptor, Bertoldo di Giovanni. Michelangelo impressed his teachers, peers and benefactor by his dedication and diligence. So sincere and hard-working was he, that he was given a key to the garden. He copied a number of the great masters such as Donatello and Masaccio so adroitly, that his works appeared better than the original! This impressed a lot of artists and the general public, what to speak of Lorenzo. As a result, Michelangelo received a wonderful offer from the great man himself – to live with the Medici children at the Medici palace! It was something he had not even dreamt of.

All the tough times he had faced as a child, seemed a thing of the past in the luxury of Lorenzo Medici’s hospitality. He was treated at par with the other children and also received the same education, besides continuing with his sculpture. He learnt a lot from the discussions that the family had about Platonism. His later neo-Platonic philosophy took root in this very environment. He also made some lifelong friendships with the Medici children. Some of them became popes; others became bankers. But most of them remained avowed connoisseurs of art, patronizing eminent artists such as Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci.

It was in the Medici garden that Michelangelo sculpted his first figures, namely The Madonna of the Stairs, and the Battle of the Centaurs when he was merely a lad of 14! When Michelangelo began his work, he was so deeply dedicated that he often forgot to change, eat or drink! The two sculptures reminded people of the old master, Donatello. Some even claimed that Michelangelo had improved upon the old master’s effort. Vasari said that the sculpture “…which so beautiful that was now, to those who study it from time to time, it appears as if by the hand not of a youth but of a master of repute, perfected by study and well practiced in that art.”

However, very few realized the torment and conflict that the young artist went through during his youthful years. In his diary, Michelangelo noted, “Already at 16, my mind was a battlefield: my love of pagan beauty, the male nude, at war with my religious faith. A polarity of themes and forms…one spiritual, the other earthly, I’ve kept these carvings on the walls of my studio to this very day.”This inner turbulence always reflected in his paintings and sculpture. Even the innovative styles he used in his architecture mirrors it. Yet, some grew envious of his success at such a young age. There was an apprentice named Torrigiano who first befriended the young Michelangelo. But later, unable to bear the sight of his success and fame, Torrigiano hit him hard on his nose. Michelangelo’s nasal bone was crushed and he had to live with this disfigurement all his life. Of course, Torrigiano was immediately exiled from Florence, but Michelangelo had to experience more gloom in his young life. Undoubtedly, this must have caused emotional trauma in an already lonely child, driving him even harder to concentrate on his work.

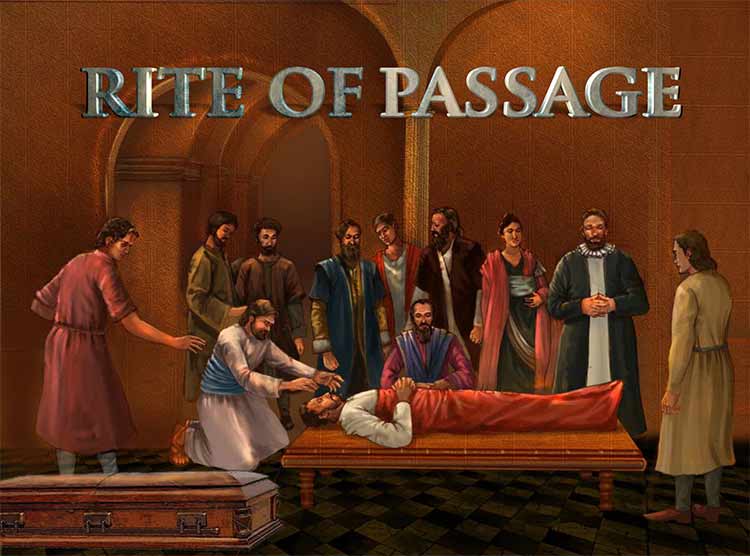

Like all good things, Michelangelo’s stay with the Medici came to an abrupt end when Lorenzo the Magnificent passed away in 1492. Michelangelo had to move back into his father’s home for some time. There he made a wooden crucifix for the Church of San Spirito; this pleased the priest, who allowed Michelangelo to use the rooms there for a rather bizarre activity: Michelangelo would go to the allotted room in the dead of night. Dead bodies would be placed at his disposal, which he would then cut up! This he did, not for any reprehensible reason, but only to study the anatomy of human beings. However, flaying corpses in the dead of night in closed chambers, cutting them open to see how the human body looked under its skin, all in partial darkness had its aftermath. Soon Michelangelo fell ill and was forced to discontinue his macabre machinations!

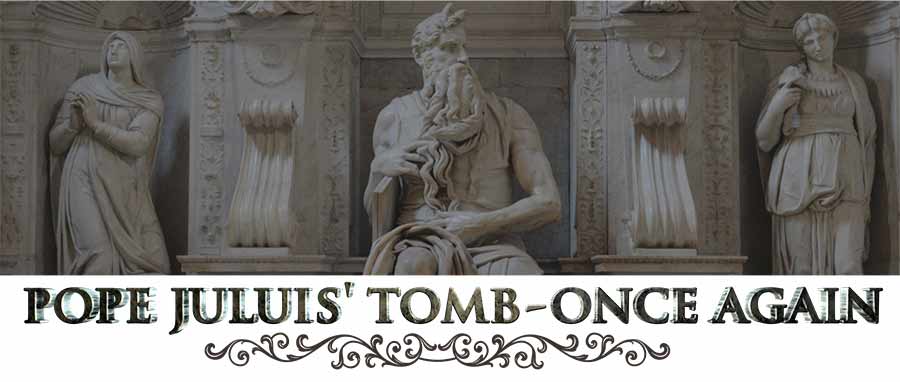

Another famous artist and engineer, Leonardo da Vinci also did the same to increase his own knowledge and impart greater realism to his own paintings. Michelangelo used this understanding with stupendous accuracy in his sculpture and paintings. For instance, his statue of Moses at the tomb of Pope Julius II bears ample evidence of his hard work in the dark chambers of the church. The hands, as they rest on the armrest, clearly display the veins, the eyebrows appear to be contracted in a majestic frown and the neck turned just slightly in a regal pose – all so life-like. They appear to be living and expressive. He also carved a massive, accurate figure of the Ancient Greek hero, Hercules which was sent to France, but disappeared later. Soon, Piero II, Lorenzo’s son, invited him to make a snow statue. As expected, Michelangelo turned out a perfect snow sculpture which was placed at the door of the Medici palace.

Unfortunately, Piero II was neither an able administrator like his father Lorenzo, nor did he expand the business much. He was often ill and was nicknamed ‘Gouty Piero’. The Medici family had to temporarily leave the reins of power in Florence in 1494. They were forced to flee because of Piero’s poor administration and high-handedness. When Savonarola, a preacher, started a widespread movement in Florence, Michelangelo thought it wise to go away for some time, as the former hated the Medici and their friends. A popular republic came into force in Florence under his rule. “Savonarola’s sacred army of inquisitor children was responsible for watching over the purity of Florence. They would go from house to house and from palace to palace confiscating all works of art which were incompatible with the faith and which were to be burnt. Savonarola was responsible for organizing several ‘Bonfire of the Vanities’ in which he burnt many rare books, manuscripts and other works of art.”

It is obvious that the citizens could not stomach such unnatural restrictions for long and Savonarola was soon ousted. In fact, he met a ghastly end along with his comrades – they were burnt alive at the stake!

Michelangelo travelled to Venice and then to Bologna, where he met with an interesting adventure. The place where he lived had a strange rule. Guests had to have a password to leave the place. Michelangelo forgot his password and was asked to pay a steep fine, which he did not have. Luckily, he was saved by Aldovrandi, a government official, who invited him to live with him. He enjoyed Michelangelo’s learned company; especially the latter’s way of reading from classical writers such as Dante, Petrarca, Boccaccio, et al. At his host’s request, Michelangelo sculpted the statues of St. Petronio, St. Proclus and an angel, which far surpassed in workmanship the other sculptures at the tomb of St. Dominic. He was compensated well by his host, and after an entire year, he returned to his beloved Florence in 1496.

At this point Michelangelo fashioned a Cupid, or the mythological God of love, for Lorenzo di Pier Francesco of the Medici family. This statue was seen by Baldassare de Milanese who said, “Why don’t you bury it in the mud so that it looks older than it is? We can then sell it in Rome at a higher price than what we may have here.” It is not very clear whether Michelangelo agreed to this deal, but Milanese definitely took it to Rome and sold it to Cardinal san Giorgio for about two hundred ducats. He cunningly asked Lorenzo di Pier Francesco to pay Michelangelo thirty crowns, as that was all he said he had received. However, the Cardinal saw through the entire trick and traced the work back to Michelangelo, as he had been impressed by the artistry. He summoned the young Michelangelo to Rome, where the latter lived as his guest for a year. Here again, Michelangelo did not know that he was staring his future in the face. Jacopo Galli, a Roman banker, recognized Michelangelo’s talent. He asked the artist to make two figures for him – a life-size Cupid and a Bacchus, Roman God of wine. Not only was the figure of Bacchus flawless, even the little figure of the Satyr was sculpted with great detail. The satyr, a mythical being with legs of a goat, is shown partially hidden behind Bacchus and nibbling at a bunch of grapes. Needless to say, the forms were so superbly executed that the entire Rome was abuzz with Michelangelo’s praises. To quote his biographer, Giorgio Vasari on the Bacchus sculpture, “In that figure it may be seen that he sought to achieve a certain fusion … that is marvellous, and in particular that he gave it both the youthful slenderness of the male… a thing so admirable, that he proved himself excellent … beyond any other … that had worked up to that time.”

In 1498, a French Cardinal, Cardinal de Billheres wanted to leave a souvenir of his visit to Rome. He requested Michelangelo to craft the Pieta, the body of Jesus after his crucifixion on the lap of his mother Mary. Michelangelo used Carrara marble to sculpt a statue so perfect and realistic that it is understandably considered one of his best works. Antony Mason, the author of ‘At the Time of Michelangelo’ says, “The naturalistic poses of Michelangelo’s figures in his Pieta, and the details of the clothes and skin, show an extraordinary ability to convert marble into something dazzlingly life-like.”

Many criticized the sculptor for depicting a young Mary, who appeared unnaturally calm in the face of such tragedy. But Vasari and others stoutly defended him saying that the Virgin, because of her purity, had a naturally unblemished appearance. There have been several interpretations besides the above about her youthful appearance. Some have said that to the Virgin Mary, Jesus, now powerless, was more like a helpless infant. Hence, although people saw a grown Christ, she saw her infant son lying in her lap. Others have said that because Jesus is one of the Trinity, Mary is a child to Jesus, as is every human being.

In his biography of the artist, Vasari eulogizes the work eloquently: “The lovely expression of the head, the harmony in the joints and attachments of the arms, legs, and trunk, and the fine tracery of the veins are all so wonderful that it is hard to believe that the hand of an artist could have executed this inspired and admirable work so perfectly and in so short a time. It is certainly a miracle that a formless block of stone could ever have been reduced to a perfection that nature is scarcely able to create in the flesh.” However, it was an extraordinary feat for a 25 year old, more so to complete the work within a year. Today, the statue can be seen in St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City. One cannot help but recollect the artist’s own words, “In every block of marble I see a statue as plain as though it stood before me, shaped and perfect in attitude and action. I have only to hew away the rough walls that imprison the lovely apparition to reveal it to the other eyes as mine see it.”

It is very interesting to note that this is the only figure in which Michelangelo has left his name. Ofcourse, there is ample reason for the master sculptor to have diverged from his custom of never leaving his signature or name in any of his works. It once so happened that he heard someone saying that the sculpture was made by ‘our Gobbo from Milan’, meaning another sculptor named Christoforo Solari. This enraged the volatile Michelangelo to such an extent that he did the unthinkable. Overnight, he took his hammer and chisel and on the sash of the Pieta he inscribed in large letters the words ‘MICHEL ANGELUS BONAROTUS FLORENT FACIBAT’ or ‘Michelangelo Buonarroti of Florence made this’. This was an unprecedented step by the sculptor; he later regretted his rash and egoistical act, vowing never to repeat such a deed!

Michelangelo was in Florence from 1499 to 1504 during which he painted the famous painting ‘Holy Family’ for the Doni family. This was done in tempera or paints mixed with egg yolk so that the paint would adhere to a wooden base. This was different from fresco painting that was made on wet wall. In the early years of the Renaissance, oil paint was not used in most of the Italian city-states. Painters used to ground colours and mix them in water according to their requirement. This was then applied to wet wall on which ‘cartoons’ or sketches had been made. The most important event in the young painter’s life occurred when members of the ‘Guild of Wool’ asked him to complete a forty-year old project of David, as a symbol of the city’s freedom and independence. (David was a Biblical hero, who killed the giant Goliath with stones hurled from his sling when the giant, belonging to enemies of Israel, came to attack king Saul of Israel).

When Michelangelo saw the colossal block of marble, he wondered how anyone could have damaged it in such a manner, for there were broken chips and holes in the block. However, the die-hard that he was, he gritted his teeth and began work around 1502. He first created a wax model of what he had visualized and then set out to shape the marble, a practice that was habitual with him. It was a gigantic task and required his entire concentration and skill. He put a barrier around the block of marble and worked in complete secrecy. When it was near completion, an amusing incident occurred. Piero Soderini, the governor of Florence, walked in. Pretending to be very knowledgeable about art, he suggested that the nose of the statue was rather thick. Michelangelo saw through him at once, but just to humour him, climbed up the scaffolding, carrying some marble dust, and pretended to chisel the nose, dropping the dust he had hidden in his hand, to the ground below. Soderini showed his great satisfaction with the ‘improvement’ and pronounced the work a masterpiece. Michelangelo, according to his friend and biographer Vasari, gleefully related the story to the latter!

The finished statue won commendation from all quarters of the artistic world. The general public and the powerful rulers and cardinals of Florence and Italy applauded it. Michelangelo’s David broke with all previous depictions of the hero. None of the others had brought out the inner turmoil of David and the contrasting outer casualness. The best of Mannerist features were visible in this painting, specially the detailed hands and facial expressions, dexterity that remains unequalled to this day. Mannerists showed realism in an exaggerated form to bring out the sense of life and dynamism in their works. In Michelangelo’s own words, “Once in place, all Florence was astounded. A civic hero, he was a warning…whoever governed Florence should govern justly and defend it bravely. Eyes watchful…the neck of a bull…hands of a killer…the body, a reservoir of energy. He stands poised to strike.”

All these features went to show how Michelangelo put his knowledge of anatomy to good use. Each and every part seemed real, “The tendons in his neck stand out tautly; the muscles between his upper lip and nose are tight; his brow is furrowed; and his eyes seem to focus intently on something in the distance. Veins bulge out of his lowered right hand…”David was shown standing with his body weight mainly on one leg. The pose invoked widespread commentary in artistic and other circles, and some even tried to replicate it. Others tried to give David a more dynamic look, but none succeeded in bringing the convincing real-life look of Michelangelo’s David.

We know from the diary of Michelangelo that this project was dear to his heart as David was the epitome of the ideal citizen and devotee, whose faith in God was such that he could face a giant with a mere sling. David was considered a symbol of Michelangelo’s own patriotism and love for Florence. David’s facial expression showed the turmoil he was going through and the amount of concentration he had to put in. Also, it was the sculptor’s way of alerting the citizens to the impending attack on Florence. Perhaps, Vasari’s words bring out the passionate admiration that a spectator may feel, “…most beautiful contours of legs, with attachments of limbs and slender outlines of flanks that are divine; nor has there ever been seen a pose so easy, or any grace to equal that in this work, or feet, hands and head so well in accord, … in harmony, design, and excellence of artistry. …whoever has seen this work need not trouble to see any other work executed in sculpture, either in our own or in other times, by no matter what craftsman.”

The next year was tranquil and Michelangelo spent it painting a fresco called ‘Battle of Cascina’ on the walls of the Florence city council. He also made the Bruges Madonna, which was later sent to the place called Bruges. In 1506, he went to Rome on the invitation of Pope Julius II who wanted Michelangelo to build a tomb for him. This Pope could hardly be called a man of peace. He was nicknamed ‘Fearsome Pope’ or Papa Terrible and was known to be a hard taskmaster. He was an aggressive and able administrator. Michelangelo accepted, but within a few months regretted it for the rest of his life. The Pope kept interrupting Michelangelo and changing his plans. Additionally, he was constantly influenced by Michelangelo’s rival Rafael, an established painter in his own right, and Bramante, another sculptor. Michelangelo made elaborate plans for sculpting the Pope’s tomb and spent many months in great discomfort in the mines of Carrara, quarrying marble. He also prepared several parts of the tomb consisting of many small statues and a large sculpture of Moses, which was majestic and conveyed a gravity that was life- like. He made many columns and statues, working partly in Rome and partly in Florence. Once all the marble had arrived in Rome, he went to the Pope to ask for money to be paid to the transporters. He was told that the Pope was away. He paid them out of his own pocket and returned the next day to the Pope.

Michelangelo never imagined what was in store for him. Not only did the Pope not meet him, he was insulted and turned away by the gatekeeper who said to his face, “Only too well do I know him…but I am here to do as I am commanded by my superiors and by the Pope.” Confused and unable to bear the insult, Michelangelo left Rome immediately, resolving never to return. He was also afraid that the Pope may harm him somehow. In those days, the Pope was not just a man of God, but also a warrior, a judge and a lawgiver. The Pope often led armies in battle, unlike popes of the modern times. Hence, Michelangelo quietly left Rome and went to Florence, which was governed by Soderini and was out of the Pope’s direct control.

Pope Julius II, on learning of Michelangelo’s sudden departure, immediately sent his envoys after him to Florence. After much intervention from many quarters, including from Soderini himself who was afraid of inviting the Pope’s wrath, Michelangelo finally asked for pardon from the Pope. The Pope forgave him, and after loading him with gifts, bade him to make a bronze statue of his. Michelangelo did this with great finesse and skill and the statue was put up in a prominent place in the city, until a few years later when it was melted to make cannons for a war. Seeing the Pope’s pleasure, Michelangelo thought of restarting the incomplete tomb. But fate had other plans for him.

Thinking that he could peacefully return to sculpting the Pope’s tomb, Michelangelo began to block marbles. However, the famous painter Raphael and his relation Bramante persuaded the Pope that it would be inauspicious to build his tomb before his death. They convinced the Pope to instead let Michelangelo paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, mainly because they knew that as a sculptor, he would not succeed at painting. Little did they know that they were mere playthings in the hands of destiny!

The ceiling of this chapel was very wide and would be exceedingly difficult to paint, particularly so for a sculptor. The Pope was readily won over, and he immediately stopped Michelangelo’s work and ordered him to start painting. Not only was the sculptor dismayed at this arbitrary order, but he was also enraged at the underhand way in which he was obstructed. Always a sensitive soul, he never expressed his pain, except by being rude and harsh to people around him. However, this he could not do with the Pope and so he took it out on various other people who came in contact with him. When he was merely in his thirties, he had gained a reputation for being uncouth and filthy in his habits. In reality, however, as his friends and disciples knew, he was a dispassionate and dedicated person. In contrast, there was his contemporary, though twenty-five years senior, Leonardo da Vinci, the reputed polymath. Although the amount of work Michelangelo did was far more copious than that of the former, Leonardo was much more popular because of his warm and friendly disposition. He was the toast of every social event in Florence, whereas Michelangelo was rarely part of the social scene. It is tragic to note that though Leonardo took very long to come up with even one piece of work, and Michelangelo was much more proficient, the former was more popular and in demand in social circles, whereas the latter was not often a sought after guest. It is said, that the latter never felt very highly about Leonardo whose nature was in contrast to his own. But alas! society judges people from their behaviour, not their inner feelings. Had Michelangelo been less sensitive and more social, life may not have been so lonely and agonizing, but then we might not have had such a magnificent body of work either. Thus, Michelangelo came to be selected to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

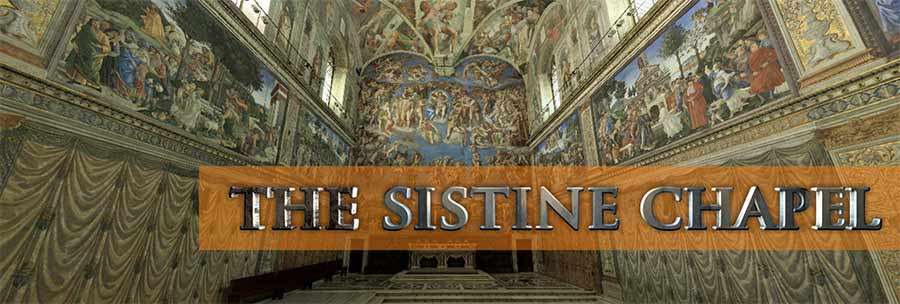

The chapel in Rome takes its name from Pope Sixtus IV, who restored it and started regular church service, dedicating it to the Virgin Mary. He was related to Pope Julius II, who wanted the ceiling painted in his memory. Although some of the walls had fresco paintings by old masters, the ceiling was not properly decorated. When the work fell to Michelangelo, he resigned himself to the tremendous ordeal it would mean for him. Bramante, his enemy, decided to prepare the scaffolding to keep a watch. Michelangelo said to the Pope, “Bramante’s work is not proper and will hinder my progress. I request your Holiness to remove the scaffolding he has constructed. I would like to do the work myself.” Bramante’s structure was immediately removed and Michelangelo made the scaffolding himself. He knew his work would involve reaching the height of the chapel and painting the ceiling with his head constantly upturned. The strain to his eyes cannot be imagined, besides the sheer physical effort required. Under all these conditions, Michelangelo had to paint the ceiling in a striking and meaningful manner. His artistic spirit took up the challenge and rather than just painting the twelve apostles, as he was asked to, he decided to paint the entire Genesis or the story of the Creation, Generation and Destruction of the world, as depicted in the Bible.

Giorgio Vasari has summed up the stupendous achievement pithily, “This work….still is the lamp of our art, and has bestowed such benefits and shed so much light on the art of painting that it has served to illuminate a world that had lain in darkness for so many hundreds of years. And it is certain that no man who is a painter need think any more to see new inventions, attitudes, and draperies for the clothing of figures, novel manners of expression, and things painted with greater variety and force, because he gave to this work all the perfection that can be given to any work executed in such a field of art.”

The famous writer Goethe said, “Without having seen the Sistine Chapel one can form no appreciable idea of what one man is capable of achieving.”

Details from the complete work demonstrated how strenuous Michelangelo’s exertions were in achieving such minutiae as he worked, face upward, sometimes for almost twenty hours at a stretch. For instance, the picture of the Libyan Sybil (clairvoyant) showed her in the act of getting up after having completed a large volume of writing. Michelangelo sketched his figures before he painted them. A sketch of the Sybil (female prophet of myth) still exists. It shows how he imagined the actual human figure as it would be in movement in all its muscular vitality. After he had sketched the entire act and the required expressions, he would then proceed to do a fresco on the wall. His remarkable paintings illustrated the arduous work that went into the depiction of such things as muscles, manner and movement. His efforts demonstrated the wholeness of the action, which is most difficult to achieve while painting in such circumstances.

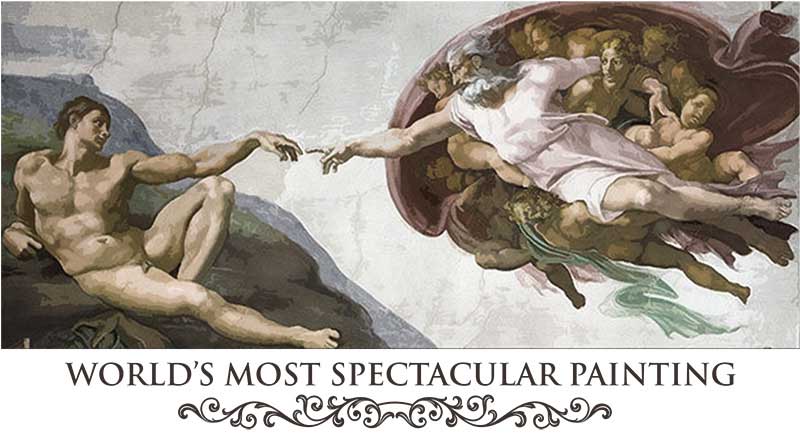

In the duration of four years Michelangelo painted twelve figures which included seven prophets and five Sybil just about the border of the ceiling, filling the inner space with scenes from Genesis. Michelangelo depicted the prophet Ezekiel as strong yet stressed and determined yet sure. As per the critics, this was symbolic of Michelangelo’s sensitivity towards the natural intricacy of the human situation. The most fabled Sistine Chapel ceiling painting is an emotion infused depiction of ‘The Creation of Adam’, in which Adam and God are shown outstretching their hands to one another.’

This was indeed the most sublime scene in the painting. The expressions on the face of the painting of God, the passion, the fire, the responsibility during the creation of Adam and his facial language conveyed the uncertainty in Adam’s heart. The attire of God, His intense gaze, his crucial gesture of bestowing life from the touch of His index finger got indelibly imprinted in the collective human psyche for all time to come. The colossal ceiling reinforces the feeling of infinitude, the smaller structures and pictures creating an ethereal ambience.

The twelve thousand square feet ceiling and upper walls were filled with painting and sculpture. In the four corners, he depicted Biblical characters, the good overthrowing the bad. One corner had the virtuous Judith, a pious woman, who had severed the head of the villainous Holofernes, who always harassed her. The story goes that she invited him to her chamber one night and with the help of her old servant, she cut off his head. The painting showed his severed head being carried by her stooping old servant in a basket. The head is in the throes of death – the depiction so real that nothing was left to imagination.

The other corner had David cutting of the giant’s head, causing the soldiers to marvel at his feat. The look on the faces of each character could be plainly understood. The third corner had the best figures of all – Moses and the Serpents. The agony of those dying of serpent bite, their bodies twisted with pain, their faces showing their silent screams – all brought out the desperation of those dying a horrible death. Finally, the figure of Ahaseurus or the wandering Jew, at repose and three members of the council that determined how the Jews would be saved from their enemies. The entire effort took four years and was completed in 1512. It was during this period that Michelangelo became increasingly careless about his own appearance and manner. He scarcely spoke to anyone, rarely changed his clothes, often working and sleeping in the same clothes, and hardly ever bathed. It is said that he took off his boots so infrequently that once when he tried to remove them, some of his skin also came off! He certainly must have found his work far more absorbing and meaningful than social engagements. Thus, his genius was established in the medium of painting also.

Michelangelo’s other monumental work, made between 1536 and 1541, was The Last Judgment, painted on the wall at the rear of the altar of the Sistine Chapel, Rome. It showed the Resurrection of Christ, and the final day of reckoning, when humans would be judged for their actions on earth. Again a colossal work spanning an expansive wall, it was filled with expressive and mainly nude Biblical characters and some pagan characters. Michelangelo used all the conventions of painting such as perspective (depth), chiaroscuro (dark and light), delineation (outline) and coloration (use of colours). He departed from tradition by showing Jesus at the centre of all the activity, rather than at the top of horizontal lines of people. Some scholars drew parallels with the idea of Copernicus’ then new hypothesis that the sun was at the centre of the earth, and Jesus being shown at the centre of the painting. The life-like facial expressions of the characters created a sense of realism. As Vasari asserted, “… it is filled with all the passions known to human creatures, and all expressed in the most marvellous manner. For the proud, the envious, the avaricious, the wanton, and all the other suchlike sinners can be distinguished with ease by any man of fine perception.”

Despite Michelangelo’s effort and superior skill, some still criticized him. John Ruskin, the reputed critic and essayist, sums up most of the criticism that has been levelled against the genius: “All that shadowing, storming, and coiling of his… is mere stage decoration, and that of a vulgar kind. Light is, in reality, more awful than darkness – modesty more majestic than strength.” Vulgarity was linked to the nudes that Michelangelo showed so unabashedly. An anecdote reveals how such an attitude angered him. Once, when Pope Paul brought a master of ceremonies, Biagio da Cesena, to see the half-done painting, the latter criticized it on the grounds that the nudity was fit for a tavern and not for a holy place. He called it disgraceful and shameless. Michelangelo was so incensed at this that he immediately put Biagio’s face to that of a painting of “…Minos with a great serpent twisted round the legs, among a heap of Devils in Hell.” “…nor was Messer Biagio’s pleading with the Pope and with Michelagnolo to have it removed of any avail, for it was left there in memory of the occasion…” in Vasari’s words.

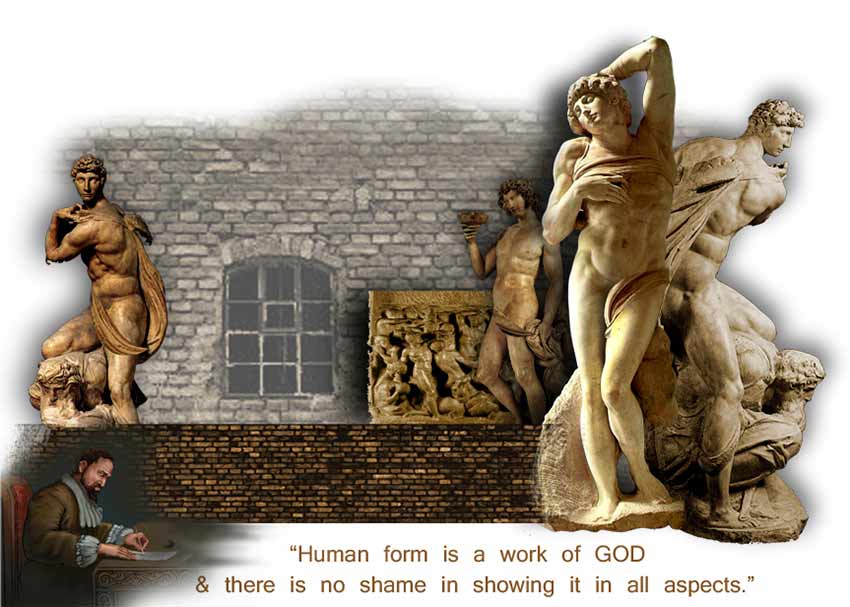

As a true artist, the work of art was uppermost in Michelangelo’s mind. Even though he was god-fearing, he felt that the human form was a work of god and that there was no shame in showing it in all its aspects. He rebutted the criticism by stating, “What spirit is so empty and blind, that it cannot recognize the fact that the foot is nobler than the shoe, and skin more beautiful than the garment with which it is clothed?” Even in his sculptures, the prudish found nudity most annoying. In fact, some officials even tried to hide the genitals of his sculpture of David with fig leaves and sarcastically called it the ‘fig leaf campaign’. Whenever royalty visited a replica kept in the London museum, a fig leaf was kept in a box to be used to cover the private parts so that they would not be shocked! In fact, throughout his career and even later, people from all walks of life tried to fault Michelangelo’s work as pagan or un-Christian because of the nudity that he portrayed.

After the Sistine Chapel ceiling was completed, Michelangelo thought that he could return to the unfinished tomb of the Pope. But how wrong he was! He had just begun blocking the marble in 1513 when he got news of Pope Julius II’s death. Although the Pope had made provisions for such an eventuality, the Medici Pope Leo X, who took over, started interrupting Michelangelo under the influence of some malicious people. Meanwhile, some of the relations of Pope Julius II even accused Michelangelo of misusing the funds generously given to him by the Pope. The humiliation and hurt embittered Michelangelo. In addition, some members of the Pope’s Medici family succeeded in convincing Pope Leo X that Michelangelo should begin work on the Medici Chapel, rather than that of Pope Julius. This happened after Michelangelo had spent many months in the Carrara quarries and got a good deal of marble. Uncaring and insensitive, the Pope’s relations influenced him and finally, Michelangelo had to leave the tomb unfinished a second time. He openly wept when he was asked to leave his work unfinished and go to Florence to start work on the Medici Chapel at the Piazza di San Lorenzo.

Michelangelo spent many months in hardship in the Carrara mines, quarrying marble. All of a sudden, Pope Leo ordered him to get the marble from the Petrasanta mines, which was in a place that was quite difficult to access. But being unfairly forced to go there, Michelangelo had no choice, especially since the Pope had been his childhood companion in the Medici household. After Michelangelo had secured the marble with great difficulty, angering the owner of the Carrara mines by suddenly deserting him, Pope Leo abruptly cancelled the contract in 1520 without any explanation. Michelangelo was crushed by this conduct, particularly because he had already made a number of wax models, drawings and other plans before starting the actual work, as was his practice. Thus, Michelangelo suffered immense physical discomfort, mental fatigue and humiliation on account of the whimsical behaviour of the Medici.

Michelangelo’s life was chaotic during this period as he kept shuttling between Rome and Florence. Pope Leo X died in 1521, an event that lay to waste his efforts of the last four years. Yet, without any qualm, the Medici family returned with a request for a tomb in the Basilica of San Lorenzo, which was fortunately completed by 1531. The tomb had many impressive embellishments. The most important were two sets of nudes: Dawn and Dusk on the side of the entrance where Lorenzo was interred. Their expressions hewed in stone clearly showed the grief they felt in the loss of Lorenzo the Magnificent. On the side where Giuliano was buried, was the other set of nudes: Night and Day. The unique architecture of the tomb as well as the placement of the statues spawned a completely unconventional style. Vasari enthuses, “…he made in it ornamentation in a composite order, in a more varied and more original manner than any other master at any time…That license has done much to give courage to those who have seen his methods to set themselves to imitate him.”

Thus he set many architects and artists free from the shackles of following a beaten track.

During the same period, the Medici family wanted their library to be turned into a public one. Michelangelo was the architect chosen, and he built what is today renowned as the ‘Laurentian Library’, a symbol of not only the Medici generosity but also Michelangelo’s versatility. He was self-trained in architecture; he never had a teacher to train him; his experience consisted of the knowledge he had garnered while building the tombs. All the same, he took up the offer. As was expected, the library turned out to be one of the most admired pieces of architecture in the world. It contained a variety of ideas woven together to give shape to Michelangelo’s conception of the ideal architectural design. The library was typical of Mannerist architecture. The receding columns looking like human bodies, the ambiguity about whether the roof is supported by walls or columns, the stairs flowing into the entrance gave the whole place a sense of dynamism. In contrast was the reading room, with its long well-lighted windows, giving the room the required serenity and quietness.

Michelangelo produced new styles such as pilasters (vertical columns against walls for the purpose of decoration) tapering thinner at the bottom and a staircase with contrasting rectangular and curving forms. Even today, the structure inspires modern architects because of its ‘living’ design. Michelangelo had to stop work midway because of the preparations for the defence of Florence from the impending attack of the Pope. He was made Chief of Fortifications and spent a long time fortifying his beloved city. Needless to say, Michelangelo’s fortification of Florence was undertaken and finished with the utmost sincerity and novelty of plan. Hence, the rest of the library had to be finished by some of his students as per his plans.

When the Medici regime became extremely oppressive, Michelangelo fled to Rome where he was threatened by the relatives of Pope Julius II, whose tomb he had left incomplete. Pope Clement helped him to sign another contract for the same tomb and Michelangelo got some breathing space. The unjustified accusations by Pope Julius II’s relations that Michelangelo had misappropriated the money given to him by Pope Julius II, however, caused him to spend many sleepless and unhappy nights.

In 1533, Michelangelo also met Tomaso de Cavalieri, a young man who was almost fifty years younger and to whom he dedicated many sonnets, madrigals and poems. In this too, he was criticized because people misunderstood his passionate verses to Tomaso de Cavalieri.

J.F.Nims, who translated his poems, clarified, “In the half dozen sonnets of 1532….he is at pains to stress the innocence of his affection, especially against the “false tongues” and their slander. He is also uneasy because, innocent as he felt his passion to be, he feared the risk of serious sin, which he refers to in the prayerful lines of a sonnet probably of that year: ‘…o hoist me up from this doomed and evil slough of error: so close to death, from God so far.”

The verses were probably a manifestation of his intense need for close relationships, which were few and far between in his lonely life. Having spent a good deal of his youth and early adulthood in the marble quarries, Michelangelo had missed out on the pleasures of life. Besides, his solitary nature did not make him an attractive company. Most social occasions had the important artists as invitees, but Michelangelo was rarely seen in any of these. These circumstances probably explain his need for close companionship. In Tomaso Cavalieri, perhaps, he saw his lost youth, what he might have been and how he could have achieved greater social grace. Notwithstanding these debacles, Michelangelo’s poetry, like all his other talents, was exalted and sometimes difficult to translate. There are many neo-Platonic ideas relating to the superiority of the spirit over the body.

To quote Nims, “… (In the) Symposium of Plato… there is a description of just such a love for ‘the divine beauty, pure and clear and unalloyed, not clogged with the pollutions of mortality and all the colours and vanities of human life: ‘It is such a conviction, writes Michelangelo, that justifies his devotion to such young men as Cavalieri… where … God shows His glory, it’s radiated veiled in some mortal form it shimmers through. And it’s such I love, for the beauty mirrored there’.”

Despite people’s malicious gossip about his orientation, Michelangelo’s poetry was like his other achievements, full of passion and ardour and greatly admired by acclaimed poets such as Wordsworth and T.S. Eliot.

Some of Michelangelo’s finest poetry was dedicated to Vittoria Colona, a Roman widow, who also addressed several poems to him. Vittoria had been engaged when she was four years old to Fernando d’Avalos whom she married when she turned 19. She was learned and much sought after by prominent suitors, but she remained faithful to her childhood fiancé. However, her marriage was destined to be a tragic one. The couple were able to live peacefully only for two years. Fernando was called away for war and they could meet only rarely, communicating through letters and poems. In 1525, Fernando lost his life in a battle, and after she had travelled to various places, Vittoria settled in Rome in 1536 at the age of 46. This is where she met Michelangelo and a significant relationship blossomed between the two. Her literary talent and his genius are evident in the sonnets and poems they wrote to one another. She usually lived in a convent close to Michelangelo’s house and they met often. She was admired in the literary circles of Florence and had several friends there. Even when they were apart, they continued to communicate with each other. An excerpt of a sonnet she addressed to Michelangelo displays her poetic skills:

“The wondrous and holy miracle by which,

through his mercy, I perceive two opposed beings,

one divine and one human, so fused into one

that God becomes a true man and man a true God,

causes my lowly desire to soar so high

and in the same way so inflames my chilly hope

that my free and candid heart no longer trembles

beneath the evil, worthless burdens of the world.”

Michelangelo confessed to his friend Condivi that he loved Vittoria. However, their relationship did not reach any conclusion, although they remained intimate. In 1547, Vittoria breathed her last at the same convent in Rome.

It was in 1545 that the tomb of Pope Julius II was finally completed, after nearly forty years of blood, sweat and tears. Unfortunately, it was not to the scale that had previously been planned. The remains of Pope Julius II were not interred in this tomb. They lie in the Basilica of St. Peter’s Cathedral next to those of his uncle, Pope Sixtus IV. In 1547, Michelangelo was invited by the Pope to redesign the Basilica of St. Peter. This Basilica or cathedral had first been built around 399AD by Emperor Constantine. Thereafter, it was constantly improved upon by various architects and sculptors, including Raphael and Bramante. This church is one of the most important in the Roman Catholic tradition because St. Peter lies buried in the centre of the church. One of the twelve apostles, he is considered the first Bishop of the church. Hence, bishops of the church are usually buried at St. Peter’s. It is curious that as long as Raphael and Bramante and their friends were alive, Michelangelo was never invited to contribute to the Basilica. It was only after their deaths, that he was called in. Many have surmised that the hostility felt by his rivals was instrumental in keeping the superior Michelangelo out of this project in Rome. When he was finally summoned, he was almost 71. Michelangelo was not very enthusiastic about this project, but the Pope would have none of his excuses.

Michelangelo accepted the Pope’s proposal on the condition that he would be given a free hand. He took up this intricate project and even at that advanced age, treated it as a sacred obligation. For him, it was a spiritual undertaking and he accepted the work without charging any fees. Here too, he did not cut corners. He demonstrated the same level of dedication and hard work that he had displayed while painting the Sistine Chapel. His age was undoubtedly a deterrent, but a mellowed Michelangelo now asked for assistants to do the minor tasks. It is noteworthy, that by now, the master artist had smoothed some of the rough edges of his nature. He was not as foul-mouthed or uncouth as he had been, probably because of the multiple positive influences in his life. He had also turned to neo-Platonism quite seriously by now. Hence, he had not only gained in reputation as the topmost sculptor and architect, but also had the illustrious mingling with him.

Michelangelo made the most spectacular changes to the structure, specially the dome that dominates the Roman skyline today. His old rival, the late Bramante, had been the earlier architect and Michelangelo gave him full credit for the work he had done. He, however, changed the angular structures of the dome and gave the entire structure a softer, more flowing design. The innovative ovoid shape of the dome was a structural necessity and not merely for decoration. As there was very little support for the dome from other portions of the structure, this became an essential requirement. His student Jacopo Barozzi and Giorgio Vasari completed some of the work after his death. Thereafter, Giacomo della Porta, a Roman architect, brought about certain modifications. Bernini, another famous architect, adapted a few important segments, yet Michelangelo’s inputs have remained mostly unaltered. It is the most imposing cathedral in the world and attracts millions of devotees and visitors. There were many changes suggested, but the ovoid dome still remains one of the architectural achievements of Michelangelo and an important attraction of the Cathedral.

In February 1564, Michelangelo worked on the Rondanini Pieta, the Virgin Mary mourning over the body of Christ. A significant feature of the sculpture was the frailty of appearance of Jesus and the Virgin Mary. It seemed to reflect the consciousness of his mortality. The interesting touch was the appearance of Jesus supporting his mother on his back. This seemed to suggest that Mary derived spiritual solace in her hour of grief from Jesus.

Later, Michelangelo developed fever, as observed by his friend Daniele da Volterra, but refused to rest and exposed himself to the cold night air. On 18th February he could no longer get up and breathed his last at the age of 88. To quote Ruffini Marco, “The artist spent his last hours in the presence of his friends Diomede Leoni, Daniele da Volterra and Tommaso dei Cavalieri and his doctors Gherardo Fidelissimi and Federico Donati. The Roman confraternity of San Giovanni Decollato, which Michelangelo had joined fifty years earlier, took charge of the burial.” His body was placed in the Campagnia dell’Assunta in Rome.

Michelangelo, when alive, had always expressed a deep desire to be placed in the earth of his beloved city Florence after his death. His nephew Leonardo, his closest relation, and his Florentine friends, including his biographer Vasari and Borghini made arrangements to bring back his mortal remains to Florence. They had decided to keep the entire event a secret, but failed miserably! On 12th March, the body was brought back to Florence. The casket was borne on the shoulders of thirty-two people belonging to Vasari’s Academy which he had dedicated to Michelangelo and taken to his tomb in Santa Croce. They found to their surprise that the premises were overflowing with the people of Florence. Leonardo and Vasari had decided that they would not open the casket for fear that the body would be decomposed after so many days of being buried. Yet Borghini threw open the cover of the casket. Ruffini eloquently describes the revelation that awaited the congregation: “What was found exceeded all expectations: the body had not decayed.” “A true miracle”, Borghini exclaimed, ‘considering that the artist had died twenty-two days earlier.’ Borghini ordered the academicians to pay homage to the artist by touching his head, one by one. It was one of the most moving farewells to a great son of Florence. Michelangelo’s tomb was designed by Giorgio Vasari and embellished by a few of his followers. The tomb epitomises Architecture, Painting and Sculpture and shows many important events of his life. The Church of Santa Croce contains the remains of many other distinguished luminaries such as Galileo and Machiavelli and therefore it is also known as the Temple of the Italian Glories.

Michelangelo’s life was spent in gruelling and devoted hard work; he was often berated and tortured by people who took him for granted. But for Michelangelo, his work was his life. He never married nor had any children. All his hours were spent in giving tangible shape to what can only be called divine inspiration. He lived a frugal life, with no airs or demands. He was generous even with those who stole from him, as was the case with a model for his poetry, Fibo de Poggio. Others were ungrateful, except for Tomaso Cavalieri about whom many have made inapt statements based on Michelangelo’s eloquent poems addressed to him. He never affected geniality to please anyone. He proverbially wore his heart on his sleeve, and most of his emotions were plainly visible. This may also be the reason that Michelangelo had devoted followers such as Giorgio Vasari and Paolo Giovio, his biographers, and Condivi, his apprentice who constantly remained with him. They always vouched for his decency and purity, often talking about his monk-like austerity.

During his long life, Michelangelo encountered almost every human vice and virtue. At a young age he learnt to stoically keep away from societal contact because of his social ineptitude. But this only made him hide into his own shell. It was his work, his inspiration, his observation of human nature and luckily the presence of some friends that helped him to lower his defences to an extent. But those close to him never left him, seeing his vulnerability as well as his genius. Vasari opined, “Truly his coming was to the world…an exemplar sent by God to the men of our arts, to the end that they might learn from his life the nature of noble character, and from his works what true and excellent craftsmen ought to be.”

A colossus such as Michelangelo comes to earth only rarely. The best tribute to this master is in his own words:

“The true work of art is but a shadow of the divine perfection.”

Michelangelo’s fresco painting was not as recognized as his sculpture, so he called his friends from Florence to help him. But after seeing their sketches, he was quite upset. He refused to speak to them, and so they had to return shamefaced to Florence. Michelangelo decided to shut himself up and not allow a soul to see what he was up to. Unbelievably, he ended up completing the enormous painting all by himself. Even the Pope was not allowed to see it, although he kept interrupting the sculptor. But cautious after the previous dispute, the Pope left him alone for some time. However, Michelangelo had some trouble with the paint, which would break out in wet patches in different spots. He asked the Pope to hand over the work, one third of which was complete, to another artist. But the Pope sent an expert, who took care of the problem. After half of it was done, the Pope forced him to show it to the rest of the city, as he himself was stunned by the beauty of it. Raphael and Bramante were lying in wait and as soon as they saw it, Raphael immediately copied his style and Bramante requested the Pope to give the remaining half of the chapel to Raphael. Michelangelo immediately put a stop to their devious plans by explaining Bramante’s conduct to the Pope, and also exposing the defects in their work. Ofcourse, the Pope would have none except Michelangelo’s work and so the conniving plot of the two men came to naught. In about twenty months from then, Michelangelo, at the Pope’s constant intrusion, threw open the Chapel on All Saints’ Day, November 1, 1512 for the world to behold.

Biography of Michelangelo | 4 Comments >>

4 --Comments

I feel it is valueble for those who are in the dark and would like to learn about Michelangelo. Thanks!

Michelangelo a unique artist whose work will always be a treasure....

Basically wonderful infographic. We appears to be a lot of time gone in that undertaking. Most people out and about through cyberland we appreciate you your time and efforts.

Leave Comment.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked.

Michelangelo.. one of the great painter of that era..!!