“It is by his courage; please observe, by his courage alone, that a gentleman can make his way nowadays. Whoever hesitates for a second perhaps allows the bait to escape which during that exact second fortune held out to him. You are young. You ought to be brave for two reasons: the first is that you are a Gascon, and the second is that you are my son. Never fear quarrels, but seek adventures. I have taught you how to handle a sword; you have thews of iron, a wrist of steel. Fight on all occasions.”

--Ch. 1, The Three Musketeers

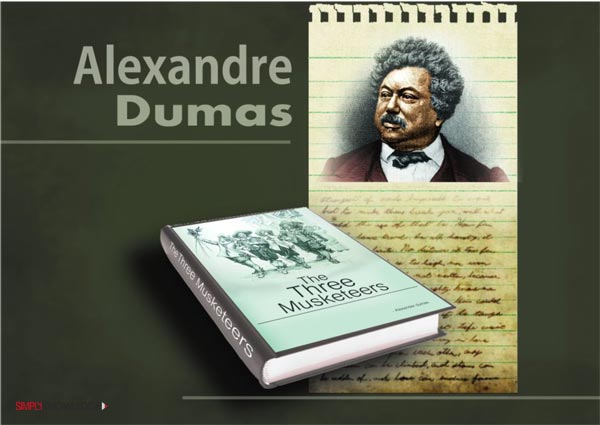

Young D’Artagnan’s father gives him the above advice while he sets off to Paris to become a musketeer. He becomes good friends with Arthos, Porthos and Aramis, meanwhile embracing their motto of “One for all, and all for one”. And while the book serves as an inspiration to millions to fight it out in life with utmost courage and honesty, the man to be thanked for it is Alexandre Dumas. Having given classics like ‘The Three Musketeers’ and ‘The Count of Monte Cristo‘, French playwright, historian, and author, Alexandre Dumas Pere was one of the best known writers of the 19th century.

Known for high adventure novels, his themes explored such things as history, loyalty and justice. No wonder his novels reverberate through the hallways of time, echoing through history as some of the best works English literature has ever seen.

A Family of Fighters

Alexandre Dumas Pere’s grandfather, the Marquis Alexandre Davis de la Pailleterie married a black slave Marie Louise Cesette, with whom he had fallen in love with in San Domingo. Their son Alexandre Thomas was to become a general of Napoleon’s army. He said, “I want to go away and be a soldier." Alexandre-Antoine, his father who was an aristocrat did not oppose him but gave approval on a condition that, “Thomas-Alexander should not enlist under the noble name of Davy de la Pailleterie, but under that of his mother, the black slave of "Jeremy's Gap." Thus he took his mother’s last name, thereby calling himself ‘Thomas Alexandre Dumas’.

According to the family’s tradition, the name Alexandre was passed onto the future generations as well. At half past five in the morning of 24th July, 1802, Alexandre Dumas Pere was born to Marie Louise Labouret, daughter of an innkeeper and Thomas Alexandre Dumas in the village of Villers-Cotterêts, a small country town, about forty miles from Paris.

General Dumas wrote to his friend, General Brune “I have to announce to you that my wife yesterday was delivered of a son who weighs nine pounds and measures eighteen inches. If he continues to grow outside as he has grown inside, he bids fair to attain a very fine figure.”

Madame Dumas was quite anxious that her son might turn out to be black. The reason for her anxiousness was a marionette show she had seen before his birth. A black devil named Berlick had carried away the main character. Berlick had scared her out of her wits and she went home saying “I'll be ruined! I shall give birth to a Berlick!” Far from it, Alexandre turned out to be a fair skinned, light haired and blue eyed boy.

Alexandre had the traits of his brave father whose heroic strength was applauded by Napoleon, who made him a general at the age of 31. However, a consequent fall out on account of his criticism of the Egypt campaign saw Thomas Dumas being ostracized from the army. A long imprisonment led to severe deterioration of his physical and mental health. When he returned home after 20 months, he was lame, deaf in one ear, partly paralysed and penniless. A combination of ill health and dire financial conditions took the better part of him, consequently leading to his death in 1806, when young Alexandre was just 4 years old.

Early Childhood Shapes Up

The loss of his father left Alexandre in despair. He could not believe that such a strong and physically big man could disappear suddenly. Young Alexandre did not accept his father’s death. On being told that his father was taken away by God, he commanded with the naivety of childhood that he wanted to go to heaven to see him. Alexandre’s novels in his later life reflected many of his father’s deeds and real life exploits.

The second was Monsieur Deviolaine who was connected to the Dumas family. He was the forest inspector of a thirty thousand acres land. A good friend to Madame Dumas, he was a person of tough exterior but a kind heart. The third was M. Collard de Montjouy, a member of the legislative body who owned a lavish Chateau three miles from the main town. Here, young Alexandre spent his days in merrymaking and happiness, roaming about in the wide open spaces. Just as the earlier house was associated with Buffon, this one was associated with a nicely illustrated bible. Meanwhile, all of it was supplemented by Robinson Crusoe, the Arabian Nights and a Mythology for the young. Such myriad experiences added onto the child’s learning and knowledge.

It was precisely Alexandre’s rendezvous with mythology in childhood that influenced his writing in many ways. Readers of Alexandre’s works will notice how frequently he draws from this branch. Madam Dumas now decided to send her 10 year old son to a clerical seminary. But Alexandre wasn’t too keen on joining it. However, after enough persistence from his mother, young Alexandre gave away his reluctance to join.

On the eve of the departure, Alexandre went ahead to buy himself an ink stand. At this point, Miss Cecile Deviolaine intervened since she dreaded her cousin becoming a priest. She ironically remarked that she would later take him as his father- confessor. Alexandre did not take kindly to her jibes and in a flurry of the moment flung the ink stand stating, “I will not go to the Seminary”.

The outcome of such a trivial issue was much bigger and much positivity was to emerge from it. The young lad ran away into the forest, leaving a note for his mother to reduce her anxiety and hid there for three days. He took shelter in the hut of a native, whose chief occupation was bird snaring and poaching.

Alexandre returned on the persuasion of Abbe Gregoir, another friend of his. This time though Alexandre’s mother was not too keen on keeping him at home and found her son a local tutor to teach. His education was shaping up in the form of regular lessons sporadically marked by holidays. It was then that he was invited to visit Abbe Fortier, a simple man with fondness for food, billiards and most importantly the gun. The young lad witnessed a world of activity like never before and developed a love for sports. Accompanying Abbe on hunting and shooting expeditions, Alexandre eagerly waited for a time when he would get to hold the gun. Developing an innate taste for the wild, he overcame natural obstacles with ease.

When Alexandre returned after a fortnight from his sporting escapade, the mother and son made Rue de Lormet their home, close to where her son had been born. A routine marked by lessons, sojourns in the forest and play followed here. When the lad experienced bouts of emotional upheaval, he would visit his father’s grave. Daily walks to the cemetery to talk to his father and the addition of graves each month moulded his sentiments and lingered on till the later years of his life.

When Disturbance Strikes

The peaceful routine was broken amid disturbing public events. Alexandre was 12 when the Allied Powers begun to invade France. Napoleon, who was till now a victorious hero, was now known more as a destroyer who was draining France and separating men from their wives, sisters from their brothers and mothers from their sons. When Soissons, a town sixteen miles from the main land was invaded, the civilians gathered their belongings and hid in caves.

Alexandre witnessed two contradictory and opposing sights at once: the show of war and the reality behind it. None of it was forgotten by him. On account of all this, his education witnessed a break. His school days ended prematurely since Abbe Gregoire had to give up teaching students in school due to some regulations. Henceforth, he visited pupils at their own houses. This is how Alexandre received education from Gregoire in Latin.

Education Beyond Education

Alexandre’s informal education consisted of some tuition in fencing among others. Consequently, his moral and religious training was given by Madame Dumas which lent him an emotional and spiritual outlook towards life. Honourable and generous, the boy had imbibed such traits of his father.

Alexandre possessed fearlessness for the open grounds, for fresh air and the wild. He had inherited a love for sports from his father. He was always eager for sports, except for the fear of heights. He was outgrowing that phase of ‘chasing’ and now wanted to be in firearms, in the company of real sportsmen. He no longer wanted to be known as a little boy, instead wanted to give wings to his to-be-found early adolescence. The vagaries of nature quickened his imagination, creating a love for nature and a disliking towards the humdrum city life. He also developed a passion for travelling. All of this was to influence his writing in the later years.

Youth Flourishes

Alexandre had his first apprenticeship in 1818 at a local notary. The notary being a liberal, Alexandre had the privilege of reading revolutionary literature. It was here that Alexandre collaborated with Adolphe de Leuven, a young nobleman and became friends with him. Adolphe visited Villers-Cotterets and took him on his first trip to the Paris theatre in November, 1822. Passing by Theatre Francais, Alexandre observed that a play featuring Talma, the famous actor was supposed to be exhibited that day. Alexandre made up his mind that he would see the play at any cost. Adolphe knew Talma and introduced Alexandre as the son of General Alexandre Dumas. Talma called him forward and said that he must also come later to watch other plays.

A brief conversation followed:

Alexandre: Unhappily I must go back to-morrow to the country to my office, for I am a lawyer's clerk.

Talma: No need to be ashamed of that, young man. Corneille was a lawyer's clerk. (Turning to the company) Gentlemen, let me present to you a future Corneille.

Alexandre: Touch my forehead, sir, it will bring me luck.

Talma (putting his hand on Alexandre’s head): So be it! I baptize thee Poet in the name of Shakespeare, Corneille, and Schiller. Return now to your office, and be sure your proper vocation will find you wherever you are. Come, come this lad has enthusiasm: he will do something yet."

Literary Career

Returning home to break with his former employer, Alexandre started searching for novels with suitable subjects to turn into plays and plan his escape. This turned out to be simple. One evening he won 90 francs at billiards, a small fortune enough for a coach fair to Paris and sustain himself till he found his feet. Without any delay he set out to conquer Paris, bidding goodbye to his childhood.

An introduction to General Foy, the deputy of his department sought him a place as a clerk in the service of the Duke of Orleans with a salary of 1200 francs. “You write a beautiful hand”, General Foy gushed over Alexandre’s beautiful handwriting and offered him the position. While in Paris, Alexandre and Leuven started working together to produce vaudevilles and melodramas. Madame Dumas later joined her son in Paris. 1829 saw the production of Alexandre’s first play, Henry III and his Court, which met great public acclaim. A major piece of work of the romantic drama saw admiration from Victor Hugo and Alfred de Vigny, two great writers of the time. His second play Christine, produced in 1830 also became popular and sufficed his financial needs, enough to start working full time as a writer.

The mid 1830s saw the end of a cumbersome republican era which was marked by occasional riots. Alexandre professed himself as a republican, just like his father. However, the republican era of 1830 was not as aggressive as that of 1790. On 26th July, 1830, at five in the morning, Alexandre heard of the suspension of the liberty of the press. It was enough for him that the ruling government was against literary pursuits. Until then he was indifferent to politics. However, thereafter he started calling himself a republican, not knowing exactly why, but probably because his father was one.

Meanwhile in 1831, a play by the name of Antony came out and proved to be an even greater success than Henri III. It attacked conventional notions of marriage, idealised romantic love and ended in murder and suicide. As usual the critics slammed it with statements like “The most obscene play that has ever appeared in these days of obscenity!” However, the play was highly revered by young romantics. With a booming economy and an end to press censorship, the times proved to be rewarding for Alexandre in many ways.

His desire to lead an extravagant lifestyle made him understand the economics of the market and thence produce serial novels, as demanded by newspapers at that time. Intelligent that he was, Alexandre simply rewrote one of his plays into a novel titled "Le Capitaine Paul”. It also led to the formation of his production studio which churned countless stories with his inputs. He compiled an eight volume collection of essays from 1839 to 1841 on famous criminals in European history. Soon love blossomed and in 1840 he married Ida Ferrier, an actress. However, he continued to have liaisons with other women and bore three illegitimate children, one of them being Alexandre Dumas, fils, who was to become a great historian in the times to come.

Alexandre’ ability as a writer was undisputed. By 1843, he had developed fifteen plays. The historical novels which were to follow earned him a fortune but his extravagant lifestyle made him spend more than he earned. An assistant by the name of Auguste Maquet was one of the nearly seventy-three assistants who helped him write his books. Alexandre particularly weighed Auguste’s opinions. Maquet helped Alexandre outline the plot for ‘The Count of Monte Cristo’ and also made a significant amount of contribution for ‘The Three Musketeers’. However Alexandre himself added the final details and dialogues.

The mention of historical facts in Alexandre’ works was not always exact. However, he had a sharp sense and hence combined history with fiction very tactfully. On one instance at a public gathering, Alexandre described the famous Battle of Waterloo. However, a general present shouted saying, “but it wasn’t like that; I was there!” To this, Alexandre with his razor sharp wit replied “You were not paying attention to what was going on.” Alexandre earned generously, making nearly 200,000 francs annually. He also received an annual sum of 63,000 francs for 220,000 lines written for ‘La Presse’ and the ‘Constitutional’, both well know newspapers.

The Count of Monte Cristo

“There is neither happiness nor misery in the world; there is only the comparison of one state with another, nothing more. He who has felt the deepest grief is best able to experience supreme happiness.”

Edmond Dantès, the protagonist has everything going well for him. He is about to become the captain of a ship and is engaged to a beautiful and young lady, Mercedes. Marked by envy, Dantès’ so called friends plot to put him in trouble. Danglars, the treasurer of the ship, envies his early success. Fernand Mondrego is in love with Mercedes and the third one, his neighbour Caderousse does not like the fact that Dantès is luckier and more successful than him.

Together the three men accuse Dantès of treason by drafting a letter. However, accusations were true up to some extent. Dantès was carrying a letter from Napoleon for some of his sympathizers in Paris and was framed as a Napoleonic conspirator just before Napoleon’s return from Elba in 1815. He is hence thrown in prison at Chateau d’lf. After learning about the treasure on the Isle of Monte Cristo, he escapes the prison and uses the treasure for the destruction of the three men who framed him.

The book explored the character traits like no other. Known for his imaginative and gripping style, Alexandre kept the action moving in the book. He also composed the chapter endings or teasers to evoke suspense and entice the reader into reading the book.

The tale of suffering and retribution was partly inspired by a real life shoe maker known as François Picaud. The book was a humongous success when published in 1840.

The Three Musketeers

Porthos: He thinks he can challenge the mighty Porthos with a sword...

D'Artagnan: The mighty who?

Porthos: Don't tell me you've never heard of me.

D'Artagnan: The world's biggest windbag?

Porthos: Little pimple... meet me behind the Luxembourg at 1 o'clock and bring a long wooden box.

D'Artagnan: Bring your own...

Porthos: [laughs]”

― The Three Musketeers

Published in 1844, the story talks about international and political chaos and struggles in 17th century France. Said to be one of the greatest adventure novels of all time, The Three Musketeers marked the power struggle between King Louis XIII and Cardinal Richelieu and a time of conflict between England and France.

The protagonist, D’ Artagnan, a young fellow leaves his home in Gascony to go to Paris and dreams of joining the musketeers, who are responsible for protecting the royal French family.

However a lot of hurdles were to come his way. It started with him being beaten up and robbed of a valuable possession – A letter of recommendation without which he would not be allowed the honourable musketeers.

Soon after he continues towards Paris and meets The Three Musketeers namely, Porthos, Athos and Aramis. The first meeting with the musketeers goes poorly. However, on being challenged by six of Cardinal Richelieu’s guards, D’ Artagnan and the musketeers become allies and battle it out with the guards. They ultimately stand victorious.

A series of complications follow, from political assassinations to kidnapping, from international espionage to murder. Meanwhile, D’Artagnan is faced with an arrest warrant. The unscrupulous and unprincipled Milady de Winter attempts to kill him. Milady’s character is one of intrigue. As a nun, she seduced the priest and stole valuables from the church. She became a spy for the Cardinal and it is later revealed that she was the wife of Athos, who after knowing the evil fact disowned her.

The eventual outcome sees the Cardinal being impressed by D’Artagnan’s courage, clearing him of all the charges.

Alexandre does not penetrate deeply into the psychology of his characters. In fact he identifies them with descriptive tags, for e.g. the lean acerbity of Athos and the spirit of D’Artagnan. The main characters possess a sorority and exhibit valour. These add onto the amazing adventure and suspenseful story.

Alexandre never followed any writing rules except the ones of his heart. His characteristic style was affable and indeed moved the reader.

The story has been extremely popular and has continued to be read by generations after it was originally written. Not only this, the book has been adapted into several movies and TV series too.

Vital themes are explored in the book, firstly friendship: this forms an integral part of the book. The four young men combine each other’s strengths and defeat evil powers. Friendship is seen as a source of support in the story. Secondly the importance of loyalty: Loyalty in ‘The Three Musketeers’ is an absolutely binding faith. In order to protect themselves, the characters depend on each other’s loyalty, which is explored through risk-taking adventures. And last but not the least Pride: Portrayed as men of immense pride and self-respect, the characters do not take kindly to any insults. In order to preserve their pride, they are seen fighting for their lives.

Critical Reception

A large part among Alexandre’s fan base was the English-speaking world and the French readers. Critics most notably applauded him for his dramatic writing which have since generations been recognized as groundbreaking. Inspite of applaud on one hand, Alexandre was often the centre of harsh criticism. His works were laughed off with shallow descriptions like ‘mere entertainment’, nothing more substantial than ‘The Wandering Jew.’ He was compared to other established writers of his time namely, Hugo, Balzac and George Sand.

Alexandre’s writing style was rampant with excessive quotations and dialogues. The astounding output of his works often left others wondering about the authenticity of the production under his name. However, he proved in his later works that collaboration was not an absolute requirement for production on his part, and observers have pointed out that no joint authorship has ever been claimed for any of his widely praised non-fiction works.

The sheer number of adaptations of his works reiterates his position as a great writer. He was truly a creative talent much beyond the literary milieu of his times. Critics have continued to investigate his works of lesser popularity for their contemporary relevance.

In 1851, in order to escape his creditors on account of rising debts, Alexandre went off to Brussels. After spending two years in exile, he returned to Paris. Alexandre lived life lavishly and was termed as ‘the king of Paris’. His fortunes were spent on friends, arts and mistresses.

There he founded a daily by the name of Le Mousquetaire. He travelled to Russia in 1858 and to Italy in 1860 where he remained in Naples as a keeper of museums. His story “La Terreur Prussienne” was produced after he visited the battlefields of the Austro Prussian war of 1866. Inspite of having told Napoleon that he had written 1200 volumes, he was at the mercy of his creditors.

The Death of a Hero

After having lived an extravagant life, it was difficult for Alexandre to live like a commoner. He was habituated to living a bohemian life, one of pleasure and peace. His deteriorating health largely confined him to his home where he was in the constant company of his books:

“Each page recalls to me a day that has gone by. I am like one of those trees with thick foliage full of birds that are silent at noon but that wake toward the end of the day. At night-fall they will fill my old age with the flapping of wings and with songs.”

Alexandre delved his being into reading ‘The Three Musketeers.’

However, with time depression, anxiety and gloom started shrouding Alexandre. He kept saying, "Tout passe, tout lasse, tout casse!" (meaning ‘nothing lasts’).

In October, the rains and fog made the environment gloomier. Alexandre no longer left his room. Through his window he watched the autumn set by. Often Alexandre tried to justify why he was left with no money.

He said to his son “People say that I have been wasteful. There's no truth in it. I came to Paris with two louis in my pocket; go and look in my waistcoat, and you will find those two louis.”

Being penniless gradually became an obsession so much so that people around him made it a point to fill his drawer with money. Alexandre often worried about the longevity of his works. The writer in him nagged his soul to know if readers would continue reading his books long after he was gone.

Alexandre asked his son one day: “Tell me, Alexander, on your soul and conscience, do you believe that anything of mine will live?”

"Never fear....” said the son, and with great sincerity he went on to explain how there was no doubt about the posterity of his works. Hearing this, Alexandre’s face lighted up. However, the very next day Alexandre’s condition deteriorated. When the priest gave sacraments and called him by name, he moved his eyelids but did not have the strength to reply. At ten in the night on December 5, 1870, he died without any significant indications.

“Tell the angel who will watch over your future destiny, Morrel, to pray sometimes for a man, who like Satan thought himself for an instant equal to God, but who now acknowledges with Christian humility that God alone possesses supreme power and infinite wisdom..... There is neither happiness nor misery in the world; there is only the comparison of one state with another, nothing more. He who has felt the deepest grief is best able to experience supreme happiness. We must have felt what it is to die, Morrel, that we may appreciate the enjoyments of living.

Live, then, and be happy, beloved children of my heart, and never forget that until the day when God shall deign to reveal the future to man, all human wisdom is summed up in these two words,--"Wait and hope.”

--Ch. 117, The Count of Monte Cristo

Posthumous Recognition

Alexandre Dumas remained in the cemetery he had been buried in at Villers-Cotterets until November 30, 2002.

In a televised ceremony in 2002, the then French president Jacques Chirac ordered for the transfer of his body to the Pantheon of Paris, the great mausoleum where French luminaries were interred. His coffin was draped in a blue-velvet cloth and flanked by four men dressed up as The Three Musketeers.

In an interview that followed the ceremony, the president acknowledged the presence of racism that had previously existed and believed that with the transfer of the body alongside notable writers like Victor Hugo and Voltaire, a wrong had been rectified.

Alexandre’ passion knew no bounds. No wonder he went onto battlefields to gauge the real scenario, which was to ultimately give him a sense of the catastrophe; influencing his writings.

"With you, we were D'Artagnan, Monte Cristo or Balsamo, riding along the roads of France, touring battlefields, visiting palaces and castles, with you, we dream." said French President Chirac in his speech.

Next Biography