A spontaneous decision between Ernesto Guevara and Alberto Granado; and the choice was made. They planned to embark on a South American Odyssey. The question arose, How? The answer was standing right outside: Alberto’s motorcycle, ‘La Poderosa II’! They packed their provisions, food, medical kit and books, and loaded it on the rear of the motorcycle.

The two carried their entire life for the next eight months tightly packed in a couple of haversacks. On the morning of 4th January, 1952, Ernesto’s family stood on the street besides La Poderosa chattering away, wishing them luck for a safe travel. Ernesto hugged his family goodbye, promising to write regularly. The two adorned their aviator hats, placed the goggles over their eyes, Alberto kick started La Poderosa, Ernesto sat in the pillion seat and the journey began. The adventurous young Ernesto, who was studying to be a doctor, was embarking on the journey of a lifetime. Whizzing through the curly streets of Buenos Aires, La Poderosa caught the eyes of pedestrians walking down the road as it passed by. The vigorously spirited sound of the engine was left echoing in their ears. On the other hand, Ernesto and Alberto were the perfect image of travellers dressed in rugged attire, a thirst for adventure and meagre means of travel. Their journey took them traversing the countryside and La Poderosa began devouring kilometres in the melodiously gruff sound that only an adventure seeking traveller would truly understand. Alberto and Ernesto gazed at the thicket and forests as they continued their journey. Their ears heard the sound of the pristine ambience, with birds chirping and the wind blowing past them which was empowered by the loud and masculine sound of La Poderosa.

(Sound of the Motorcycle)

Duub Duub DuubDuub. Dddrrrrrrrr dddrrrr ddddddddrrrr dddddd…………

(Sound of Gunshots)

Bang…. Bang…. Bang… Bang……..

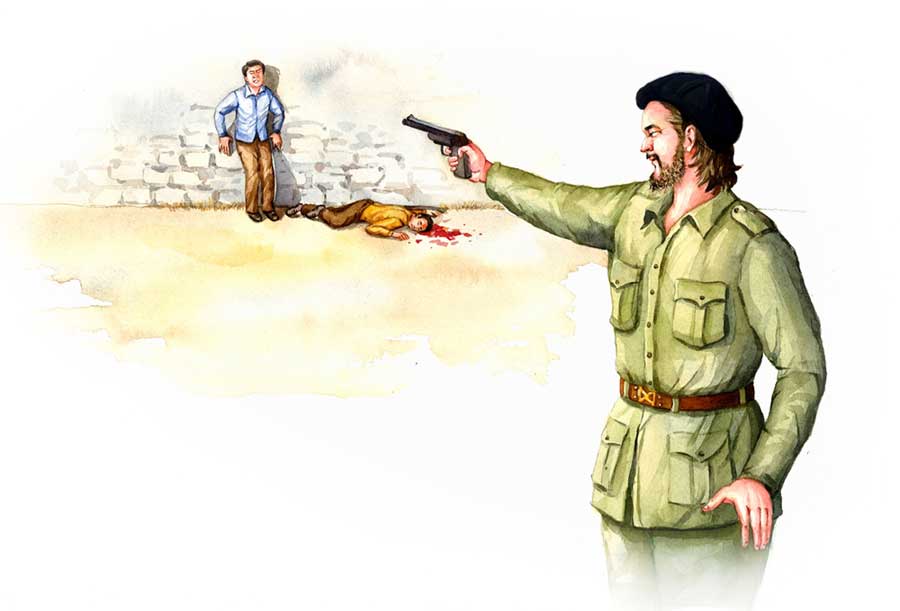

Amongst the thicket of the forests, the comrade crew is running helter skelter. One minute, they were resting in a sugar cane field in Alegría de Pío and the very next minute they were bombarded with bullets from all directions. The morale and the energy of the crew was diminished as they had been walking for a couple of days. The attack on December 5, 1956 came as a complete shock and left the crew completely dismembered. A crew of 82 was exterminated and brought to 12. The sound of the bullets echoed in the ears of the remaining comrades, empowering the sound of the quiet ambience of the wild. Many of Che’s fellow comrades were injured or dead in the revolutionary bloody battle while they were on their way to Sierra Maestra, Cuba. Che himself came face to face with death for the first time, when he was shot in the neck by President Batista’s army. The injury was not fatal, but he was stunned by the swiftness and effectiveness of the attack which left the entire group in tatters. It was at that moment, Che described his predicament saying, “Perhaps this was the first time I was faced with the dilemma of choosing between my devotion to medicine and my duty as a revolutionary soldier.”

These were the two most significant chapters that shaped his life and transformed him from a young asthmatic boy into a thrill seeking traveller, then a lifesaving doctor and finally into a Guerrilla hero. This is the transformation of Ernesto Guevara de la Serna into “CHE GUEVARA”.

Asthmatic Adventurer

Seated at the tail of the South American continent, Argentina is surrounded by Chile to the west, Bolivia to the north, Uruguay and Paraguay to the northeast and the vast Atlantic Ocean to the east. The country boasts of a wide array of geographical elements and bio diversity. The culture and lifestyle of the Argentine people had been greatly influenced by the immigrant population which was mostly European and individuals from different countries like Germany, Spain, Ireland and Italy settled in Argentina in the early 19th century. Spanish explorer and conquistador, Juan Diaz de Solis was the first to step in Rio de la Plata, Argentina in 1516, but was killed shortly by the native Indians who were trying to resist foreign invasion. After a series of unsuccessful attempts to set base on the Argentinean soil, on October 21, 1520, Ferdinand Magellan finally sowed the seeds of Spanish acquisition. He first stepped foot on Tierra del Feugo which is located on the southernmost tip of the South American mainland. This invasion came with immense amount of Spanish influence and great cultural change. With time, Argentina grew into a culturally diverse and progressive country. It was bustling with different cultures and en route to modernization. Amongst the Latin American countries, Argentina was enjoying a premier position when it came to progress and with the break of the 20th century, Argentina was transforming into one of the world’s most important countries.

Situated in northern Argentina, Rosario by the early 1920’s saw almost half of its population to be foreigners, many of whom had immigrated to Argentina during World War I. Rosario was also the home of the Guevara family. The first Guevara ancestor immigrated to Argentina from Ireland around the 1740’s and soon became one of the wealthiest landowners in Rio de la Plata. Over the years, the Guevara’s became one of the most affluent families of the region. Ernesto Guevara Lynch, an intellectual being with strong political views, carried forward the name and family inheritance. A builder and an entrepreneur, Ernesto owned a yacht building business and also tried his hands at ‘yerba mate’ (type of tea) plantations. On the other hand, Celia de la Serna belonged to a family of wealthy landlords with Spanish lineage. She was a liberated and educated young woman, who challenged many existing gender biases and social norms. A courtship began between Ernesto Guevara Lynch and Celia de la Serna, and the two were soon joined in matrimony in the year 1927. Celia was bearing good news and was expecting their first child. She gave birth to a son and the couple christened him Ernesto Guevara de la Serna. Ernesto being the father’s first name, Guevara the family name and de la Serna being Celia’s maiden surname.

The birth certificate stated the child was born on 14th June, 1928, but Ernesto Guevara’s biographer, Jon Anderson who authored the book, “Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life”, mentioned that the actual date of his birth was a month earlier, i.e. 14th May, 1928. The reason behind the alteration of the date of birth was said to be because Celia was expecting the child before marriage and in the late 1920’s, such a news would have only created a row for Celia in the society.

The Guevara family continued to live in Rosario, which is situated on the banks of the La Plata River and boasts of a humid temperate climate. Their family began to grow and Ernesto was now among the company of four siblings, who included Celia, Roberto, Ana Maria and Juan Martin. The family fondly nicknamed Ernesto as “Tete” and “Ernestito”.

It was a particularly cold day on 2nd May, 1930, when on her way back from the yacht club, Celia discovered that her son Ernesto was very ill. She immediately rushed with him to the local physician who diagnosed him to be suffering from chronic asthma. Ernesto was just reaching the tender age of 2 when he suffered his first asthma attack. Over the next couple of years, his parents tried every imaginable cure, but the climate of Rosario was not favourable for him. His asthma attacks just kept worsening and the couple was advised to relocate to a place with a drier climate. In order to help improve their son’s health, they then decided to move to the quaint town of Alta Garcia in 1932, located in central Argentina in the province of Cordoba.

The drier climate of Alta Garcia did help improve Ernesto’s health considerably and the family took special care of his well being, in terms of the food he ate and activities he would perform. Due to the uncertainty of his asthma attacks, Ernesto was homeschooled until the age of 9. Celia taught him French and the two spent most of their time reading together. While being schooled at home, Ernesto’s love for the great outdoors began to grow as he frequently went out for excursions with his family exploring the countryside of Alta Garcia. In 1937, he was then enrolled in a primary school named ‘Colegia San Martin’ in Alta Garcia and later attended the ‘Santiago de Liniers School’ and the ‘Victor Mercante School’. During his primary school days, Ernesto was tagged as a mischievous boy, but he also exhibited leadership qualities from that very young age. His primary school administrator, Elba Rossi de Oviedo said, “Many children followed him during recess. He was a leader, but not an arrogant person”. She described him as an intelligent and independent person and mentioned, “he never sat at the same desk in the class room, he needed all of them.”

Ernesto Guevara Lynch and Celia de la Serna did not believe in inflicting any ideology on their children and wanted to raise them to be liberal free thinkers. Therefore, religion was an eluded topic in the Guevara household and the parents did not speak much of it, unless they were criticizing the conservative and stringent norms of the Catholic Church. However, Ernesto as an infant was baptized as a Roman Catholic in order to please the wishes of his grandparents, but his parents asked for him to be excused from religion classes in school.

In the year 1936, a conflict between the Fascists and Republicans began to erupt in Spain. Ernesto’s parents were anti-Fascists and anti-Nazi and the unstable situation began to grasp the interest of the Guevara family. Ernesto was exposed to the highly political situation and would hear about the developments of the war in Spain through the talks that would carry on in the household. His father, Ernesto Guevara Lynch was also part of the anti-Nazi and Pro-allies group called ‘Accion Argentina’ and by the time Ernesto reached the age of 11, he joined the youth wing of the organization. The political views of his leftist parents strongly opposing the fascist ideologies were an integral part of the development of the young Ernesto. People who knew Ernesto during his youth, described his personality as that of a boy who was decisive, had strong views and displayed physical fearlessness and leadership qualities.

By the year 1942, Ernesto began to attend the ‘Colegio Nacional Dean Funes Secondary School ’ which was 45 kilometres from Alta Garcia. It was a liberal school, which was strictly against discrimination and Ernesto would travel by bus every day to Cordoba. After Ernesto was enrolled in secondary school, the family then shifted to Cordoba in 1943 and here he became friends with Tomas, his classmate and his elder brother Alberto Granado. At school, soccer turned out to be one of his preferred sports and he played at the position of the goalkeeper. He ran around the field with agility and always had his inhaler at hand. Ernesto also began to take active part in sports and stamina building activities to help deal with his asthma. He learnt to swim, began cycling and played games that required physical exertion and endurance. Ernesto’s parents encouraged him to participate and take up as many sporting activities as possible, as they believed it would help improve his breathing problems. With time, Ernesto’s varied interests kept growing. He learnt horse riding and became an avid golfer. He loved raising his intellectual quotient and participating in brain stimulating activities like reading and playing chess with his father. He spent a lot of time in his father’s library, which he turned into his literary playground. Ernesto transformed into an avid reader and would devour books of many great writers like Carl Gustavo Jung (Swiss psychologist), Alfredo Adler (Austrian medical doctor and psychotherapist), Sigmund Freud (Austrian neurologist and the founding father of Psychoanalysis), Pablo Neruda (Chilean poet), Federico Garcia Lorca (Spanish poet and dramatist) and many others. He also read the works of Karl Marx (German philosopher, economist and revolutionary socialist and founding father of the theory of Marxism) and was a great admirer of Gandhi (the pre-eminent leader of Indian nationalism in British-ruled India).

Ernesto did not want to limit himself to institutional teachings and as a student was not interested in scoring high grades. He had an inclination towards learning new things and most of his interests were outside the purview of his educational qualifications. He began to show interest in books, adventure and history like his father and also showed interest in fiction, literature, philosophy and poetry like his mother. Ernesto’s father said that his wife Celia was “attracted to danger” and this was a trait she had passed on to Ernesto as well. By the age of 17, his rebellious defiance and carefree attitude towards rules and regulation became a cause of concern and his secondary school grades were a reflection of it. Ernesto excelled in literature, history and philosophy but struggled with subjects like Mathematics and English.

On the familial front, Ernesto received great freedom and affection from his father and shared a very special bond with his mother; a bond of utmost trust and complete transparency that kept deepening with time. With every passing moment, he was growing into a young, bold and decisive individual, who his peers began to respect and admire, but Ernesto came with his quirks. He would brag very proudly to his friends about not having a bath or changing his clothes on a regular basis due to which they nicknamed him “Chancho” (Spanish for ‘Pig’). His friends would also tease him calling one of his shirts, ‘the weekly shirt’ as he would change it only once a week. One of the reasons for Ernesto not bathing on a regular basis was the threat that water could trigger an asthma attack. Nevertheless, Ernesto did not care much for his appearance and would always take the comments of his friends in a jovial spirit.

The Guevara family followed a very bohemian form of lifestyle and abided by very few social conventions. During his schooling days, the Guevara household had no proper schedule for guests and Ernesto’s friends could visit anytime they wished. There was constant noise in the house due to the mixture of people from different sections of society visiting at any given time, his father’s motorcycle, “La Pedorro” meaning “The Farter” that would create a loud noise anytime he would leave or reach home and the bustling of five children mischievously playing around the house.

In the year 1946, at the age of 18, Ernesto graduated from the Colegia Nacional Dean Funes in Cordoba. He, along with his friend Tomas then decided to study engineering at the University of Buenos Aires. He also did apply to work in the military, but was given a medical deferment due to his asthma. The same year, Ernesto’s paternal grandmother fell sick. Ernesto rushed to be by her side and cared for her for 17 days after which she breathed her last. To everybody’s astonishment, Ernesto then made the decision to pursue medicine and enrolled for medical studies. After the death of his grandmother, the family moved to the Argentinean capital, Buenos Aires and lived in her home. To add to Ernesto’s grief, he also heard the news of his boyhood hero Mahatma Gandhi being assassinated on 30th January, 1948, and felt deeply distressed.

Ernesto carried on with his medical studies and simultaneously picked up many part time jobs like working at the municipality of Buenos Aires and as a nurse on a merchant ship. He also worked as a research assistant in the clinic of Dr. Salvador Pissani. It was here that he got interested in the treatment of allergies associated with asthma. He then went on to become great friends with Dr. Pissani and his family. Whatever spare time he had, he occupied it with reading, travelling and sports like rugby, soccer and chess. At this point in time, Ernesto was nowhere near the path of realizing his political ideologies or life’s motive. He was just travelling with the urge to seek knowledge and adventure.

Road Trip

Years passed by and Ernesto was growing into a well aware intellectual being who displayed a zeal for adventure, and frequently went on trips exploring the vast landscape. He grew to love travelling and his father described him saying, “His obsession with travelling was just another part of his zeal for learning”. In the year 1950, he embarked on his first solo trip touring central and northern Argentina on a bicycle to which he had attached a small motor. Ernesto was only 22 when he embarked on the 4500 kilometre journey, during which he met with his friends, Tomas and Alberto Granado in Cordoba. At that point in time, Alberto was studying lepers at the leprosarium ‘del Chanar’ near San Francisco. Ernesto was intrigued by his research and decided to spend the next couple of days learning and helping him. After his meeting with Alberto, Ernesto carried on with his journey and went northwards, meeting natives, workers, vagabonds and other socially and economically inflicted individuals. Ernesto journeyed with the bare minimum and at times would request if he could sleep in vacant jail cells and empty hospital beds. His first experience with travelling around the country helped him witness the brutality and harsh duality of the situation of the indigenous people and the working class, ‘The Proletariat’. On his very first trip, Ernesto learnt that the superficial European culture was a ‘luxurious façade under which the country’s true soul lay; and that soul was rotten and diseased.’

He arrived back home and returned to being a medical student at the University of Buenos Aires and working at Dr. Salvador Pissani’s clinic. It was after this trip that Ernesto fell in love for the first time with a fine-looking girl named María Del Carmen “Chichina” Ferreyra. The young lovers met in the October of 1950 at a family friend’s wedding. Chichina was a strikingly beautiful 16 year old who belonged to one of the wealthiest families in Cordoba. On the other hand, Ernesto belonged to an aristocratic family leading a bohemian lifestyle in Buenos Aires. The match of the blue-blooded heiress with the bohemian intellectual seemed like an affair that was destined to be doomed, but Ernesto could not see the many obstacles between him and Chichina as he was deeply in love and wanted to marry her. There was the age gap, the difference in their social class, the disapproval of their relationship by Chichina’s parents and the geographical distance between the two. These were the many reasons for the differences that were soon to be seen in their relationship.

Ernesto however, kept visiting Chichina as often as possible. By mid October 1951, on one of his visits to Chichina, he also met with his friends Tomas and Alberto in Cordoba. It was a fine day, Alberto was working on his Norton 500 motorcycle that he had lovingly named La Poderosa II, meaning the “The Mighty One”; and the two began to discuss the idea of venturing on a year long expedition. Alberto and Ernesto discussed over the many possibilities and the places they could visit. They began fantasizing about sailing through tropical seas and travelling through Asia. The fantasies kept building in their minds, when suddenly they came up with the thought:

Alberto: – “Why don’t we go to North America?”

Ernesto: – How?

Alberto: – On La Poderosa, man!!

That very instant, one of the most important trips of their life took shape. At that point in time, both Alberto and Ernesto were at odd junctures of their life. Ernesto was tired of medical school and giving examinations and Alberto too was dissatisfied with his job and decided to quit it for the trip. Ernesto was a year away from completing his medical degree when he decided to give up his education to embark on the trip with Alberto Granado. The journey for the two began a long time before they actually set out, as Alberto began preparing La Poderosa for the South American Odyssey and Ernesto in the mean time, appeared for examinations in as many subjects as possible. Alberto also undertook the task of planning the journey and picking up the route. Their travel fantasy was slowly turning into reality.

When Ernesto broke the news, his family was amazed to hear of his plans and his intention to travel for a year, particularly because of his love affair with Chichina. The relationship was undergoing strain and a year away would only aggravate the issues between the two. His father in particular was not very receptive of the idea of Ernesto leaving his medical studies to go on the trip, but he kept his apprehensions to himself as he was not willing to stop his son from doing what his heart wished.

The day to begin the South American Odyssey was here. On 4th January, 1952, Ernesto and Alberto packed all their provisions, food, books and other important essentials and strapped them to the rear of La Poderosa. They carried their entire life for the journey on the back of the Norton 500 motorcycle, the load of which was weighing it down. Alberto was chatting up with friends and family, while Ernesto bid goodbye to his parents and siblings. Ernesto shared a very deep bond with his mother, and bidding goodbye to her, he promised to write regularly. His father, with all his apprehensions still supported his decision to travel and provided him a gun for his safety, took him aside before he left

and said, “You’ve got some hard times ahead. How can I advise against it, when it’s something I’ve always dreamed of myself? But remember, if you get lost in those jungles and I don’t hear from you at reasonable intervals, I’ll come looking for you, trace your steps and won’t come back until I find you”. These words of Ernesto Guevara Lynch to his son displayed his silent concern, and in response to his father’s anxiety, Ernesto promised that he would write to him frequently.

Alberto turned on the ignition, Ernesto sat on La Poderosa’s pillion seat and the trio began their journey. There was an excitement in Alberto’s and Ernesto’s voice, but it could not match the great sound of the Norton 500 motorcycle. Ernesto and Alberto along with La Poderosa were now moving towards their dream trip, riding down the dusty road, devouring kilometres on their journey northward. La Poderosa II made an unflattering sound, which left pedestrians and spectators staring at them. According to the route planned, they would travel through Argentina, Chile, Peru, Columbia, Venezuela and finally reach their pit stop Miami, in the United States of America.

The route was decided in a manner to accommodate a stopover in Miramar for Ernesto to meet with Chichina. The differences in their relationship were now becoming very apparent. While he was there, Ernesto tried very hard to have Chichina to commit to wait for him, but she did not give him her promise. Chichina instead gave him $15 to purchase a scarf for her from their final destination in the United States of America. After his meet, the trio then carried on with their journey and travelled northward. Weeks later, Ernesto received a letter when he reached San Carlos de Bariloche. A local post office in Bariloche had been formerly decided to be the spot where Ernesto would pick his mail before he carried on his journey further. On his arrival there, he had a letter from Chichina awaiting him. He was disastrously greeted with the news that she had decided to move on and not wait for him. He was shattered to read the news as she was his first love, but he gathered himself together after realizing that he could not convince her to change her decision.

The very next day, Alberto and Ernesto crossed into Chile. La Poderosa was already showing signs of exhaustion and was now beginning to trouble the two. They wondered if the motorcycle could carry on the journey till the very end. Numerous tire punctures and unexpected halts caused their journey to be elongated and on February 27, 1952, the trio was disintegrated with La Poderosa taking her last gasp in Los Angeles, Chile. They made many vain attempts to bring La Poderosa back on the road. Alberto and Ernesto then somehow managed to arrange for a lift for themselves and La Poderosa to Santiago.

They halted at a garage where the mechanic informed them that La Poderosa was in a state of no repair. Its life span had been exhausted, and therefore they bid their final goodbye and left the corpse behind in the garage in Santiago. The two were left distressed over leaving La Poderosa, but were also worried of how they would continue their journey ahead. They were not travellers devouring kilometres anymore, but were sniffing dust as they slowly crawled the vast distance. With La Poderosa not being with them anymore, their speed decreased exponentially. They had to now depend on walking and bumming a ride and their freeloading skills were put to test. Though they were running low on money and were worried about food and shelter as well, yet, nothing could deter them off the path to their South American Odyssey. They carried on with their journey taking one day at a time.

Travelling through Chile, Ernesto was deeply touched and had a change of conscience due to the circumstances and situations he witnessed. He stated in his diary an incident about an old woman who had a weak heart and was also suffering from asthma. He mentioned of the poor state in which she lived, with the stench of stale sweat and dust filled in the air. He elaborated her miserable state by mentioning that the only luxury in her house was the dusty armchairs. Ernesto felt powerless as a doctor when he glanced at her living conditions. For him, her situation was the condition of the proletariat, and this saddened him.

While in Chile, Alberto and Ernesto visited the largest copper mine of the country at Chuquicamata. On the way, the two made an acquaintance with an elderly couple, who displayed again the suffering of the people. The elderly couple was an example of the suffering of the poor and the working class of the world. He described them as “a living symbol of the Proletariat the world over”. The open pit copper mine in Chiquicamata was U.S owned and the working conditions were unfavourable and hazardous for the Chilean workers. The mine workers received very little wages for the work they did and the risk they undertook for their life. Ernesto also mentioned in his diary that their guide had informed them that the mine workers were planning a strike against the U.S Corporation for the unruly treatment. The company was ready to lose thousands of pesos a day to the strike, but was not ready to pay the poor workers a little extra wages. Ernesto was enraged by the inhumane treatment of the working individuals at the mine.

The horror they witnessed carried on as they travelled to Peru, where Ernesto saw another example of oppression and exploitation with the native Indians. In his diary, Ernesto made references to the injustice suffered by the Indians at the hands of the Whites and the Mestizos (a mixture of European and American Indian roots). Their journey carried on and so did their encounters of watching the suffering of the people. In an incident in Colombia, which Ernesto described in his diary, he mentioned, “There is no more repression of individual freedom here than in any country we’ve been to, the police patrol the streets carrying rifles and demand your papers every few minutes, which some of them read upside down.” Their encounters with injustice and the suffering of the proletariat due to the imperialist attitude continued through their journey in Latin America.

The 8 month trip brought Ernesto adventure and learning, but most importantly, it provided him a glimpse into his very own conscience. He became aware of the ill-effects of imperialism on the proletariat. He saw firsthand the indifference and the agony of the poor and felt an urge to do something to help bring a change in their situation. The journey was coming to its end, but Ernesto was now beginning the journey into his conscience. Alberto decided to stay back in Caracas where he was offered a job and Ernesto returned back to Buenos Aires to complete his medical studies. Ernesto touched many lives during his trip, but the many people whom the bourgeoisie thought to be insignificant, touched and changed his life dramatically. Ernesto wrote many letters and also made notes of his travels which were later compiled to be published in a book named “Motorcycle Diaries”.

Ernesto returned home but his thirst for adventure and learning was yet to be quenched. He embarked on another trip with his friend Carlos “Calica” Ferrer. This was Ernesto’s second Latin American Odyssey and he, at this point of time was just 25. He kept notes of this trip as well, which were included in a book called, “Back on the Road”. They set out for their journey on July 7, 1953. It was during this trip that Ernesto attained a deeper understanding of the situation of the proletariat. His outlook changed from being a medical doctor from Argentina to following the revolutionary path. Ernesto and Calica travelled from Argentina to Bolivia. During this trip, when Ernesto arrived in La Paz, he met with a group of Argentine exiles, one of them being a young lawyer named Ricardo Rojo. He also met people with strong political ideologies, but he himself was still uncertain about the mission of his life.

After Bolivia, Ernesto now left for Peru and planned to visit Machu Picchu and Cusco. He mentioned in his diary that he had visited the archaeological site before with Alberto and missed him immensely. Calica was enthusiastic about the journey, the travelling and the places they visited, but Ernesto wished for Alberto’s company saying, “the way in which our characters were so suited to each other is becoming more obvious to me here in Machu Picchu.”

Their journey carried on to Ecuador, where Ernesto met with Ricardo and three other leftist Argentine law students. It was one of them; Eduardo “Gaulo” Garcia who jokingly brought forward the idea to Ernesto and Calica, to see the revolution in Guatemala. This spontaneous thought stuck with Ernesto and he decided to move towards Guatemala with Gaulo and reached there by the end of December 1953. While in transit, Ernesto met with a number of revolutionaries and political leaders like Juan Bosch, the famous revolutionary nationalist leader of the Dominican Republic, exiled Venezuelan political leader Romulo Belancourt and Costa Rican Communist leader Manual Mora Valverde.

In Guatemala, Ricardo then introduced Ernesto to Hilda Gadea. She was a Peruvian exile, who was a militant member of Peru’s leftist political party, APRA (American popular Revolutionary Alliance). She had found political asylum in Guatemala due to the dictatorial regime of General Manuel Odria, as they tagged them as outlaws and began to persecute them. The Jacobo Arbenz government at this stage, provided refuge to a lot many political exiles all over Latin America. Hilda helped arrange a place for Ernesto and Gaulo to stay. She described their first meeting saying, Ernesto had a commanding voice but fragile appearance. His movements were quick and continuous, but he also portrayed himself to be a very relaxed and calm person. He was intelligent and very precise with his comments. She noticed, they were dressed in casual clothes but when she spoke with them, she realized there were many layers to their personality.

With time, Hilda became close friends with Ernesto and he discussed with her the details about his previous trips and adventures. He told her about his friends from childhood and also about his first girlfriend Chichina. Ernesto spoke at length about his family, which impressed Hilda immensely. The way he spoke, she could recognize the admiration and warmth he felt for his mother.

Through Hilda, Ernesto met with many other political refugees and exiles. They met with a group of Cubans, who were part of an unsuccessful assault on the Moncoda military barracks led by the famous Cuban communist revolutionary Fidel Castro, in Santiago de Chile on 26th July, 1953, against the dictatorial rule in Cuba. Hilda and Ernesto were impressed by the Cuban exiles and among them Antonio “Nico” Lopez particularly struck them. Nico displayed a certain conviction in Fidel’s revolution, believing, he was the only one who could bring about a revolution in Cuba. He said, “Fidel is the greatest and most honest man born in Cuba since Marti.” Jose Marti was a Cuban poet, journalist, revolutionary philosopher and political theorist who, through his political activities and writings, played an integral part in Cuba’s independence against Spain in the 19th century.

Ernesto carried on living in Guatemala, but had no proper job and stable form of income. He kept in touch with Hilda and met with personalities of great political views through her. Among the many other individuals of Hilda’s circle was a North American professor named Harold White. He had written a book on Marxism and asked Hilda if she could help him translate it to Spanish. Hilda knew of Ernesto’s financial situation and was completely aware that he was in need of money. She also knew Ernesto had his pride and would not take money from anyone, so she recommended Ernesto to White. However, since Hilda spoke better English and Ernesto knew more about Marx, the two began working together on the book. The friendship between Hilda, White and Ernesto grew over time, with White and Ernesto discussing topics varying from Marxism , Lenin ( Russian communist revolutionary, politician and political theorist), Engels ( German political theorist and author who put together the Marxist theory along with Karl Marx), Stalin ( Russian leader and the head of the government of the then USSR) and Sigmund Freud ( Austrian neurologist and the founding father of psychoanalysis) .

By this time, Ernesto was also romantically interested in Hilda, but she did not encourage him. In February 1954, Ricardo Rojo and Eduardo Gaulo Garcia made plans to leave Guatemala, but Ernesto decided to stay due to his romantic interest in Hilda and the revolutionary activities. Ernesto’s financial situation however, was not particularly great as he still did not have a job and was not ready to work on something which was against his ideals and related to the bourgeoisie society.

By March 1954, Ernesto asked Hilda if she was interested in him and that he eventually intended to marry her. Hilda graciously accepted she loved him, but her involvement in the revolution was more important to her. Ernesto even proposed marriage to her in the form of a poem in which he said that it wasn’t her beauty alone that he desired, but her being a comrade was even more attractive to him. According to Hilda, Ernesto’s letter was beautiful and though she did not say yes to marry him, they did decide to become lovers. Ernesto’s growing consciousness was widely seen as the years kept passing by and his revolutionary spirit kept growing. By May 1954, in a letter Ernesto wrote to his mother, he said, “I could become very rich in Guatemala, but by the low method of ratifying my title, opening a clinic and specializing in allergies. To do that would be the most horrible betrayal of the two I’s struggling inside me: The socialist and the traveller”.

His letter showcased his want to denounce the rich, elite and bourgeois life and his intention to develop his being into a socialist and a revolutionary; and most importantly, the letter described his want to always remain a traveller.

A change occurred in the situation in Guatemala when an aircraft flew across the border and began open firing at people and military bases in broad day light. The attack came as a complete shock and caused great losses. The Arbenz regime in Guatemala was said to be “Communist Infiltrated” and aligning itself with the Soviet Union, due to which the attack was carried out. After the attack, Ernesto enlisted himself in the medical brigades and the youth patrol to assist during the situation of turmoil. During this time, there were high probabilities of Ernesto being imprisoned or even executed had he not taken refuge in the Argentinean embassy. During these trying times, the love between Ernesto and Hilda began to deepen. Due to the situation of unrest that had engulfed Guatemala, Ernesto then decided to head to Mexico, but Hilda chose to stay back. Before he left, the two discussed their plans for the future and Ernesto very jovially said, “I have not insisted lately… because things being the way they are, there is no possibility of starting a new life. But in Mexico we will get married.” A couple of days later, Hilda then saw Ernesto off to the train station.

During the time he lived in Mexico, Ernesto made ends meet by working as a street photographer. Hilda on the other hand, would journey to Mexico time and again to meet him. The two developed a deep sense of disdain for the U.S government. Ernesto and Hilda both blamed the U.S government for overthrowing the Arbenz regime in Guatemala and believed it to be the reason for political repression and economic and political crisis. Ernesto also mentioned that he was in touch with Nico Lopez in Mexico. Nico informed Ernesto that he was in contact with the happenings of the revolutionary 26th July Movement in Cuba and that they expected Fidel and Raul Castro to come to Mexico after they were released from the prison.

Ernesto was then introduced to Raul Castro by Nico after he arrived in Mexico. Raul and Ernesto got along very well and through Raul, Ernesto learnt that Fidel was coming to Mexico. Raul also informed him that they were organizing the 26th July Movement in Cuba.

Guerrillero Heroico (Heroic Guerrilla)

Early July, and Fidel arrived in Mexico. Ernesto and Fidel’s first meeting lasted for almost 10 hours. They ended up talking about the Latin American and international political affairs. Hilda mentioned, Ernesto believed that Fidel had deep faith in Latin America and thought he was a new type of political leader who was modest and dealt with firmness towards his cause. Fidel had deep conviction that by fighting President Batista’s regime in Cuba, he was fighting the imperialist regime that helped Batista stay in power. By now, Ernesto believed that the cause and suffering of the world’s proletariat was due to the imperialist regime and he was quite impressed with Fidel who was fighting for the cause. Ernesto told Hilda, “He will make the revolution. We are in complete agreement… I could only fully support someone like him”. Their first meet was the foundation of the long association they shared. After that first acquaintance, they went on to meet three or four times a week. After Hilda met with Fidel, both she and Ernesto were in awe of him. She asked Fidel as to why he had come to Mexico, to which he replied, he had come to organize and train fighters who would help invade Cuba and stand against Batista and the imperialist influence in Cuba. According to Fidel, Ernesto had decided to join the 26th July movement the very first night they met in Mexico.

By early August, Hilda was bearing good news and informed Ernesto that she was pregnant. On hearing the news, Ernesto asked for them to be married as soon as possible. Ernesto was 27 and Hilda was 33, when the two got married on August 18, 1955, in Tepotzotlan, outside Mexico City. Raul Castro was among the guests present at the wedding ceremony.

Fidel then left Mexico for the United States to gather funds and support from the Cubans supporting the movement. By the end of 1955, the movement was catching on and Raul, Fidel and Ernesto began to meet on a regular basis. This movement, however, brought a certain anxiety in Hilda’s mind over separating from her new husband and the father of her child, but that was nothing compared to the pride she felt to be associated with the cause. The preparations carried on and Ernesto began to train and prepare himself mentally and physically for the invasion.

On February 15, 1956, Ernesto became the father of a girl. They christened her Hilda after her mother and fondly called her Hildita. Fidel was one of the first to visit them in the hospital and he took the little girl in his arms and with great conviction said, “This girl is going to be educated in Cuba”. Ernesto was mesmerized by Hildita. He was a doting father and showered her with care and affection.

Ernesto simultaneously also carried on with his training and was transforming into one of the strongest comrades among the 80 men who were going to invade Cuba. It was during this period of training that Ernesto also received his nickname “Che” (a Spanish interjection commonly used in Argentina and Uruguay, which translates to ‘friend’, ‘mate ‘or ‘pal’.) His fellow comrades bestowed this name on him as he used the word excessively while addressing and conversing with anyone. The training camp, resounded the words “Che” and Ernesto was very happy to accept the affection of his comrades in the form of his new nickname. Ernesto was now proudly accepting himself to be “Che Guevara”.

By April 1956, the training camp was growing stronger for the cause. However, by late May, the questioning and suspicions of the government authorities regarding Che and his position in the revolution had become prevalent. Hilda too was questioned, watched and put under police surveillance by the Mexican authorities. During this time, Fidel and the group of comrades, which included Che, were detained for having no proper immigration paperwork. The comrades were soon released, but not Che; he was detained for almost 2 months. Hilda and their daughter visited Che often in prison. After the release, the preparations for the invasion were on, and in the November of 1956, 82 members including Che, hopped on board the boat named ‘Granma’. The comrade crew left the Mexican port of Tuxpan on November 25, 1956 and began their journey to Cuba. The journey brought them bad weather and many other difficulties, and on December 2, 1956, they disembarked on the south eastern shore of Cuba.

The chosen landing spot for the ‘Granma’ was near the coastal town of Niquero, which at that time was called the Oriente Province. However, the Granma arrived two days behind schedule; and because of low fuel it sank anchor on a beach called Playa de los Colorados, which was 15 miles south of the decided landing spot. The spot where they landed was muddy and marsh- like which made it difficult for them to unload all their weaponry; hence, they had to leave behind all the heavy equipment. The comrade crew, then for many days, marched through swamps and thick forests, moving towards Cuba’s largest mountain range, the Sierra Maestra. To avoid being seen by the enemy and Batista’s army, they hid during the day and travelled during the night. The first couple of days, they did not see any resistance, but three days after stepping on the Cuban soil they were surprised, when on December 5, 1956, they encountered a column of Batista’s army near a sugar cane field in Alegria de Pio, where the group had stopped to rest. Their first encounter was a major setback, as the sudden attack caused confusion and caught them unawares. The attack caused a humungous loss of lives also, out of which only Fidel, Raul, Che and 12 other comrades were able to make their way to Sierra Maestra. During this encounter, Che was shot and received injury in his neck, but the wound was not serious.

He received minimal medical treatment, as he had left his knapsack in Alegria de Pio. He described his first episode with armed revolution in the essays he later wrote, “Episodes of the Revolutionary War”, saying, “Perhaps this was the first time I was faced with the dilemma of choosing between my devotion to medicine and my duty as a revolutionary soldier. There at my feet was a knapsack full of medicine and a box of ammunition, I couldn’t possibly carry both of them; they were too heavy. I picked up the box of ammunition, leaving the medicine, and started to cross the clearing, heading toward the cane field.”

On December 2, 1956, the Mexico City newspapers published the news of Fidel Castro’s expedition and the headlines read as follows, “Invasion of Cuba by boat – Fidel Castro, Ernesto Guevara, Raul Castro and all other members of the expedition dead.” Hilda read the news and was grief stricken, but she was cautioned by friends to wait for a confirmation of the bad news as the Cuban and Mexican government could be spreading false information about their deaths. She was informed later that Che was alive and well. Their small group of 12 was then joined by another 6 distraught peasants by January 1957 and the group gained momentum and started operations again like a Guerrilla force. Their first victory was an attack on a small army garrison on the coast which raised the spirits of the small group on a massive mission. As months passed by, the guerrillas carried out many victorious attacks on Batista’s regime in the region. With their strength growing as they received urban support in form of men, arms, food and ammunitions, Fidel and Che carried out their revolution in Sierra Maestra. Che had joined the revolution as a medical officer, but with time, he turned into a valuable Guerrilla leader. He began to garner respect and admiration from his fellow comrades for his fearlessness, simplicity, character and comradely attitude. Due to Che’s growing admiration among the comrades and his dedication towards the revolution, Castro provided him with great military responsibilities. He promoted him to the rank of Captain, and on July 21, 1957 he appointed him as Commander or Commandante. This was a great honour for Che, as Commandante was one of the highest ranks in the Guerrilla army and till then, only Fidel held that title. On this occasion, Che’s fellow comrade, Celia Sanchez gave him a star which he proudly wore on his black beret, which became an iconic part of his personality.

On November 4, 1957, Che Guevara published the first issue of El Cubano Libre (The Free Cuban) which was the newspaper of the Rebel Army. A couple of months later, he also played a significant role in establishing Radio Rebelde and began transmissions by February 1958. Rebelde broadcasted news about the actions of the rebel army and speeches from Castro, political view points, messages and declarations of the 26th of July Movement.

While Che was now working for the revolution from Escambury Mountains located in central Cuba, he met Aleida March, who served as a clandestine arms courier, saboteur and messenger. She was formerly a school teacher in Santa Clara before she joined the 26th July Movement and had been recognized by Batista’s authorities for her covert actions. Aleida informed Che that she had been ordered to be placed under his command. At first, Che refused her to join in as a combatant and asked her to stay as the column’s base camp nurse, to which she argued saying she had two years of experience working clandestinely for the movement and she was prepared to be a Guerrilla fighter. Che then offered her the post of his personal secretary which Aleida accepted.

By December 1958, two years after stepping on Cuban soil, the revolution was taking a favourable turn and had progressed from Sierra Maestra to Santa Clara, which was a transport and communication hotspot. Aleida knew the city well and began to guide Che. During this time, a certain closeness and care began to erupt in their minds and they both began to worry about each other’s safety. Che mentioned to Aleida an incident during the attack, when they had to cross the street almost directly in front of the tank that was firing at them. He admitted to her that he couldn’t even imagine the thought of anything happening to her. His confession was the beginning of the love that grew between them.

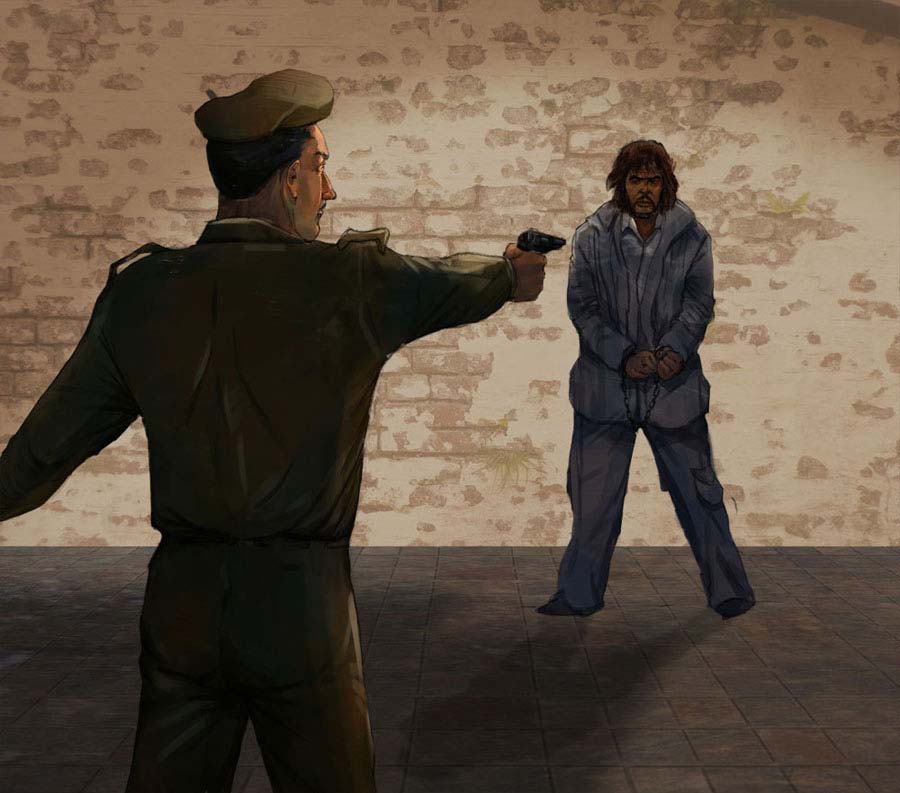

The siege by Che’s Guerrilla force carried on and by 1959 they gained control over the city. When the news of the surrenders in Santa Clara reached Havana, Batista fled from the country. The battle of Santa Clara was over. The battle against Imperialism and Batista’s dictatorship was won by Fidel, Che and their comrades. This gained him enough regard and at the age of only 31, Che grew into a world renowned revolutionary leader. After the world recognized the revolution, Che rode triumphantly with Fidel and Raul. Fidel and his allies undertook power and formed a new revolutionary government in Havana in January 1959. Che told Aleida and his close friends that even if the war against Batista’s dictatorship had ended, the revolution had just begun. La Cabana, the fortress which overlooked Old Havana was resigned under the command of Che and became the place for public executions of the accused of the Batista regime. The fortress saw the executions of many torturers and murderers of the Batista regime. Che was called the “Butcher of La Cabana” and the U.S government, media and sympathizers of Batista went rampant making malicious comments about him.

Fidel on the other hand, compared the torture inflicted on the Cuban people as nothing less than the Nazi terror in Europe, and called the execution of the torturers in public form as fair justice.

By 18th January, 1959, Che’s parents arrived in Cuba to visit him and were greeted by Aleida, Che and his bodyguard. His parents were curious to know who Aleida was, to which Che informed them saying that she was the woman he wanted to marry. 3 days later, on January 21, Hilda and Hildita arrived, and with complete honesty Che told them about Aleida. Hilda described the incident saying, “Ernesto, with his frankness of always, told me he had another woman that he had met in the battle of Santa Clara”. On hearing of the other woman in his life, Hilda agreed for a divorce but stayed back in Cuba so that Hildita could spend more time with her father.

After the new government was formed, Che was publicly proclaimed as a Cuban citizen and he enjoyed the same rights as that of any citizen born in Cuba. With time, Fidel’s confidence in Che grew from strength to strength and he became one of the closest confidants and advisors to him. The love between Che and Aleida kept growing and they got married on June 2, 1959. Aleida continued to be his personal secretary. Aleida was 22 and Che was 31 when the two got married. By early August, Castro endowed Che with political responsibility and appointed him the head of the department of Industrialization after which Che implemented the Agrarian Reform program. Under the program, land was confiscated from huge estates and big landlords and was distributed among the poor peasants who worked on the land. By the end of November 1959, Che was appointed the president of the Central Bank of Cuba. This gave him the charge of the financial affairs of the country. He declared that no special guarantees would be given to foreign corporations. He also intended to build close ties with the socialist countries (Socialism is a political state between Capitalism and Communism. In a socialist country, the production and distribution of goods is owned by the government. Some examples of socialist countries are the People’s Republic of China, the Republic of Cuba, the Socialist Republic of Vietnam and many others).

By the year 1961, as head of the National Institute of Agrarian Reform’s (INRA) department of Industrialization, Che was the one responsible for a large number of petroleum, nickel and sugar refining industries being taken over. He also made plans to produce the necessary products within the country itself, which would in turn save the country’s foreign exchange. It was during the early sixties that the ties between Fidel, Raul and Che grew stronger. Che was now second to Raul when it came to Fidel’s confidence. In 1961, Che also wrote a book on his revolutionary activities, which was called “La Guerra de Guerrillas” (Guerrilla Warfare), which explained his military tactics and also provided a deeper insight into his personality and the Cuban revolution.

Che played a very important role in influencing the new Cuban government’s foreign relations. He actively got involved in shaping Cuba’s relations with many socialist countries neighbouring Latin American countries and countries like Asia, Soviet Union, United States and the Middle East. Che was also part of the negotiations in regards to allowing the Soviet Union to station nuclear weapons in Cuba. This decision led to the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, where the United States threatened a nuclear war if the Soviet Union did not remove their missiles from Cuba. This incident also fuelled the cold war between the two giants.

Che’s speech in December 1964 at the United Nations was an example of Cuba’s support and solidarity towards the third world countries. Che was 36 when he attended the United Nations General Assembly in New York as the head of the Cuban delegation, and in his speech, he mentioned, “Colonialism is doomed”. Che criticized the United States for its actions in Vietnam and Cambodia; its racist regime in South Africa and its imperialist role in Africa. He called the United States of America a warmongering giant.

During this speech, it was made clear by Che that Cuba was going to support the socialist countries. He said, “We want to build socialism. We have declared that we are supporters of those who strive for peace”. By 1964, it was evident to Che that his four year plan for the industrialization of Cuba was hitting aground. He and his comrades underestimated the difficulties involved in transforming Cuba from an agrarian economy into an industrialized one.

During the first quarter of 1965, Che visited countries in Africa and China. He met with the president of many socialist countries. In 1964, the rebels from eastern Congo (now Zaire) had requested help from Cuba. Che had showcased support towards Congo and Fidel had supported his decision. Che disappeared from the public eye and in 1965 resigned from his post in Fidel’s government as he did not wish for his actions in Congo to be associated to Cuba and the Cuban people. As he left the country, the rumours about the rift between him and Fidel began to catch fire, due to which, in the October of 1965, Fidel made public, the very personal letter of resignation Che had written to him before leaving for Congo. The letter mentioned about Che giving up his political posts and the Cuban citizenship. It also mentioned that Che’s actions in Congo had nothing to do with the Cuban government.

The situation in Congo was unstable, as President Patrice Lumumba had been assassinated and a neo-colonial regime had been established. Che in 1965 said, “As long as imperialism exists it will, by definition, exert its domination over the other countries. Today, that domination is called neo-colonialism”. Che thought of Congo as the beginning of the revolution he intended to bring all over Africa. On his journey to the Congo, he handpicked his group of comrades, but the revolution did not go as planned due to the incompetence, stubbornness, internal fighting and squabbling of the Congolese forces. By the November of 1965, Che left Congo to enter Cuba as secretly as he left, but the situation for him was not the same. The letter of his resignation created an awkward situation for him. Che’s return to Cuba was never made public and as soon as he reached Cuba, he began working on his next mission. He chose Bolivia to be his next site to create a revolution and began his Guerrilla journey in Bolivia in October 1966.

Che travelled from Cuba to the heart of South America, Bolivia. He did give thought to Argentina and Peru and would have loved to create a revolution in his native land, but the political situation was not favourable and so he chose Bolivia. Che had travelled to Bolivia previously with his friend Carlos “Calica” Ferrer, and had seen the political instability and the hardships of the people living there. Che arrived in Bolivia on November 1, 1966, in disguise. He entered Bolivia as a bald man with glasses, under the name of “Adolfo Mena González”. He had two Uruguayan passports with the exact same pictures, fingerprints and dates of entry and departure from Madrid Airport. In Bolivia, Che led a group of Cuban and Bolivian individuals named, “The Ñancahuazú Guerrilla”. He began creating his Guerrilla army and train individuals to help raise a revolution in Bolivia.

The pillar to any Guerrilla operation is the trust and help of the local people. Che and his comrades were unable to establish this connection with the people in Bolivia. Furthermore, the fact of him not being the son of Bolivian soil, created an obstacle. On March 23, 1967, Che Guevara’s Guerrilla base camp was first discovered by the Bolivian authorities with the information provided by the local people and two deserters. And the hunt began! The information allowed the Bolivian army to locate Che’s Guerrilla force base. The premature attack was a setback to Che and caused the whole operation to go off balance. The crew was steadily losing its strength and combat capacity as the Bolivian army was frequently breaking every possibility of hope of raising the Guerrilla force. Che’s ailing health began to take a toll, with him suffering severe asthma attacks. By August, the other column in Bolivia was ambushed and the entire crew was either killed or captured. Among the causalities to the Guerrilla column was their lone female member Tamara Bunke (Tania) who was their only source to the outside world. By September, Che’s group began to be encircled. Che suffered the loss of many of his important comrades and by the end of September, the morale of the force was nearing its end. To add to Che’s troubles, the local population provided the Bolivian authorities every possible information about the Guerrilla force’s position.

Che being a foreigner trying to create a revolution gave the Bolivian authorities an opportunity to create a negative image of him and the revolution in the minds of the Bolivian people, which in turn caused the failure of the operation.

Che mentioned in his diary, “Our conditions are the same as last month; except now the army is demonstrating increasing effectiveness in its actions and the campesinos (Spanish for a ‘Peasant’) are giving us no support and have turned into informers.” Che however continued his struggle. The first few days of October became even more treacherous and his group was reduced to 16. By the morning of October 8, Che’s location had been compromised and several companies of rangers were deployed in the region. Che and his men had stopped at a ravine near La Higuera to rest, as they had been marching all night. Fire was opened on Che’s group. Bullets were fired and this left the Guerrilla force in tatters. A bullet hit Che’s black beret and then another couple of bullets hit his leg. He was immobilized and the bullets were then concentrated in the area where he had fallen. One of his comrades rushed to help him and as they tried to escape, they ran into four rangers and were captured.

The authorities informed the headquarters that they had captured Che Guevara. He and his fellow comrades were then taken to La Higuera and placed in the town’s small school. During the night, Che was constantly interrogated by army officials. He was placed in a room with the bodies of four other Guerrilla fighters. On the other hand, the news of Che’s capture reached the highest authorities. In La Paz, a meeting between President Barrientos and the high command of the Bolivian armed forces was held, to decide as to what they would do with Che. A trial was ruled out, as this would bring attention to the issue and would fuel the communist’s propaganda. Bolivia did not have the punishment of a death penalty and if Che remained alive, his supporters would save him. The decision was made to execute him immediately and make his death look as if he died in battle.

On the morning of October 9, 1967, orders to execute Che had been passed to all top ranking officials. The decision was then transmitted to all the lower officials, but none were very anxious to carry out the task. Lots were then drawn on who would execute Che. Sergeant Mario Teran pulled the shortest straw and was now supposed to perform the execution. He entered the small room where Che waited, and Che looked into Mario’s eyes and knew at that very minute that he was his executor.

Teran fired at his target. He was asked to shoot from the face down to make his death look like he died in battle. After the shooting was over, Che had nine bullet wounds in his body. At the age of 39, the revolutionary had been put to rest. Che’s body was then wrapped in a blanket and strapped to a helicopter which flew to the small town of Vallegrande. The body was then taken to Senor de Malta Hospital and placed in a shack away from the main hospital building, where his wounds were washed, his fingerprints were taken and embalming fluids were injected in his body through an incision to his neck.

By this time, the authorities had publicly announced Che’s death and a huge crowd gathered outside the hospital to see the body of the famous Guerrilla. After the doctors finished their work, soldiers allowed his body to be displayed for the public to view. Che’s body was laid on a stretcher across the laundry sink and was exhibited for approximately 24 hours after which the body was said to have mysteriously disappeared.

The quick disposal of Che’s body by the Bolivian authorities was intended so that he would not have a proper burial spot which would allow his family and supporters a place to venerate their leader. Officials stated that his body had been buried in the Vallegrande area to save it from falling into Marxists hands. Some stated that his body was cremated. No proper statements were released about his death or burial. Che was lost in time.

CHE VIVE!

Che’s brother, Roberto Guevara, came to Bolivia to take his brother’s body back to Argentina. He was not ready to believe Che had been killed and asked to see his hands, which had been cut off and preserved in formaldehyde. Roberto was denied even this request. Later, the Argentine police experts were allowed to examine the hands and compare the finger prints. They then confirmed that the fingerprints belonged to Ernesto “Che” Guevara.

For another 30 years, the search for his remains carried on. During these years, Che became the symbol of rebellion, fearlessness and revolution. He became an idol of the many who wanted change. After his death, all through the 1970’s, many leftist students and radical individuals began to roar his words and ideologies. His famous image of 1960 with the black beret, frizzled hair and beard, adorned many mugs, t-shirts and posters. His image envisaged in front of one’s eyes when they would think of a revolution. The world recognized the might of his cause through his actions. Che has his fair share of individuals who still criticize him for being brutal and cruel, but the amount is miniscule in front of the numerous people who think his name to be synonymous with the revolution for the betterment of the proletariat.

In the late 1990’s, a two year search was undertaken to find his body. His body was then recovered in July 1997 by a team of Cuban and Argentine experts at the edge of Vallegrande Airport. It was found in an unmarked grave with six of his comrades. Che’s remains were returned to Cuba and he was finally laid to rest in Santa Clara under a statue of himself holding a rifle.

His death made him a martyr for those who opposed injustice and the social inequalities of the world. Che is called one of the most important figures in Cuban history and even today his face adorns the Cuban currency.

In Bolivia, the country where he was executed, the peasants then began to revere him as Saint Ernesto. He brought forward the ideals of anti-imperialism and humanist socialism. Che worked for the betterment of a part of the society that was facing the inhumane treatment of the imperialist attitude. Till date, he is glorified as an adventurous revolutionary who wanted to bring change to the world.

Ernesto “Che” Guevara was a traveller who wanted to learn through his journeys, and indeed, his travels taught him of the sufferings of others. He began his life to be an adventurer and lived through it understanding the pain and sufferings of the people, the peasants and the working class of the world, due to the imperialist attitude of the bourgeoisie. He transformed into a Marxist, who believed change could be brought in the world with armed revolution. The Argentinean doctor grew to become one of the military strategist, writer and the Guerrilla leader of one of the most significant armed revolutions ever.

In a poem which Che wrote in the January of 1947, he mentioned about a premonition he had about his death. The following is an extract of his poem, which was then published in Jon Anderson’s biography, “Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life”:

“The bullets, what can the bullets do to me if my destiny is to die by drowning.

But I am going to overcome destiny.

Destiny can be overcome by willpower.

Die yes, but riddled with bullets, destroyed by bayonets, if not, no.

Drowned, no… a memory more lasting than my name is to fight, to die fighting.”

Che mentioned that he was not going to die drowning. In other words, he was not going to let his asthmatic condition snatch the better part of his life away from him. He went on to write that he would be riddled with bullets, destroyed by bayonets and would die fighting. Che had predicted his death and 20 years later, he did die riddled with bullets. He died the way he wished. Che died fighting.

Next Biography