Introduction

“When you stop doing things for fun you might as well be dead.”

- Said by an ardent sportsman, nature lover, altruistic nobleman, and above all one of the greatest American writers the world has ever seen. A man who believed that he could march ahead only if he enjoyed what he did.

He was a usual man with unusual abilities, all of which he developed through his passion and determination for work. He did not know how to mince words or reason why his works witnessed strong cynicism. His enormous appetite for life flowed not only in his writing but even floored people around him. He lived life on his own terms and how! He was Ernest Miller Hemingway.

Hemingway was a writer way beyond the literary, cultural and historical milieu of his times, a writer who was set to influence modern literature with his narrative prose and irredundant themes. He showed strong allegiance to the fact that “a writer should write what he has to say and not speak it”. He was quick to mention that a writer should draw from one’s own personal experiences.

Papa (the nickname he gave himself) surely knew his trade too well, with seven novels, six short-story collections and two non-fiction works under his belt. Though his style of work was thought to be unsentimental and boorish by some, he found equal admirers in the commons and the critics.

The Early Environment

Born to Dr. Clarence Edmonds (Ed) and Grace Hall Hemingway on 21st July,1899, at North Oak Park in Chicago, Ernest Miller Hemingway was the second of six children. He had four sisters and one brother (Marcelline, Ursula, Madelaine, Carol, and Leicester). Off all his siblings his name was a concoction of Ernest Hall, his maternal grandfather and Miller Hall, his great uncle.

The Hemingways belonged to an upper middle class family; hence Ernest Miller Hemingway was brought up in an upper middle class environment. Oak Park was primarily a protestant suburb of Chicago and was deeply conservative in outlook. Values of hard work, fitness and a sense of religion were fostered. No wonder that Ernest later described it as a town of “wide lawns and narrow minds.”

Oak Park was not just a protestant street but one deluged in religious dogma, thus representing the town’s smugness. Oak Parkers ostracized urban political corruption and were aloof from mid-western Chicago. As Bruce Barton, the then Congregationalist minister put it; it was a place where “the saloon stops and the Church steeples begin.”

Ernest always detested the town for its overtly conventional and orthodox thinking. He once remarked to his mother, “Don’t worry or fret about my not being a Christian. I am just as much as ever and pray every night and believe just as hard so cheer up. Just because I am a cheerful Christian ought not to bother you.”

Childhood Years

Ernest was extremely competitive as a child and carried on this streak during his later years too. He always stood by his guns and did what he thought was conducive. He received his formal schooling in the Oak Park public school system in the year 1905. He was good at extra-curricular activities- swimming, water polo, football, debates and the like.

Ernest was a keen learner and always learnt from the best. He learnt about the civil war from his grandfathers, politics from Lyold George (a British Liberal politician and statesman) and writing from American writers like Anderson, Stein, Fitzgerald and Ford. He even learnt hunting and fishing from his father who was considered by him a tough gentleman. The family’s summer home on Walloon Lake in Michigan proved to be the perfect hunting and fishing haven for him. When he was not writing, he spent most of his time indulging in his favourite sports. He hunted all day and skated on frozen ponds in winter. He loved to read, and read books way beyond his years. From early on, Ernest showed a strong rendezvous and mysticism with courage, valour, violence and death in his works. Ernest was also a keen boxer and had his first fight in the year 1916.

A Not So Sweet Parental Relationship

Ernest’s mother, Grace, was on one hand a woman with utter vitality and beauty and on the other, snobbish and selfish. Ernest always associated his poor eyesight with his mother who too suffered from it. Grace was artistically inclined and gave voice lessons and organized concerts, hence never took to doing household chores. In fact Ed, Ernest’s father was the one who did all the grocery shopping and even prepared breakfast for his kids.

A tad part of Ernest’s feelings for his mother stemmed from her extremely rigid old school of thought. As customs in the Victorian era would have it, it was mandatory to dress boys in girls’ clothing. Ernest’s need for extreme machismo in his later years was a rebound to the imposed feminism his mother so insisted upon in his younger days.

Ernest hated his name and compared it with the stupid and shallow protagonist in Oscar Wilde’s book the ‘Importance of being Ernest’. He thought the name was extremely middle class.

Ernest was often caught in crossfire between his mother and father. His father taught him everything that would lead him to become macho. Conversely, his mother being a teacher of art and music taught Ernest the finer tenets of music. However, he never showed any interest in music lessons. He was always disturbed by his parent’s incessant quarrels and felt that his parents had failed to support him in school. “Neither of my parents would come to school for me no matter how right I was. I’d just have to take it,” he said. He often believed that the reason behind his father’s quietness and diabetes was his mother who abused her husband.

Early Works

Some of Ernest’s early works are related to his school days, when he worked on the high school newspaper called ‘Trapeze’, primarily about sports. However, at the age of 17 he took up a job at the ‘Kansas City Star’ newspaper as a junior reporter. Short sentences coupled with active verbs, authenticity, positivity, and clarity were propagated. Ernest imbibed these during his brief stint and later used them as an arsenal in his literary canon.

He once said, “On the star you were forced to learn to write a simple declarative sentence. This is useful to anyone. Newspaper work will not harm a young writer and could help him if he gets out of it in time.”

Though his upbringing made him lack straightforwardness required by a reporter, he showed utter enthusiasm and vigour in carrying out his work.

The War Experience

When Ernest graduated from high school, World War I was shaping up in Europe. Woodrow Wilson, the then president of the United States of America tried not to take part in the war. The attempts failed and the USA joined the Allies against Austria and Germany. Ernest tried to join the army on turning 18 but his poor eyesight proved to be a shortcoming. Unperturbed by the military’s decision to defer him because of this, he quickly made an effort to serve the army, though not as a soldier but as an ambulance driver. The Red Cross was inviting applications from fellowmen to serve the Italian army as ambulance drivers. He took it up and had his first war experience the day he arrived in Milan, after receiving orders to be placed there. An arms and ammunitions factory exploded, wounding several men. He quickly carried the mutilated bodies to a morgue. Soon after, on July 8th, 1918, Ernest suffered his first major injury from an Austrian Mortar. As Ted Brumback, a fellow ambulance driver wrote to Ernest’s dad, that in spite of being bruised with around 200 shrapnel or small pieces of ammunition, Ernest quickly endeavoured to pick another wounded soldier rather than catering to his own self. In what could be termed as a benevolent act and a stupendous mark of valour, Ernest did not blink an eye before reaching out to his fellow soldiers.

Such kindness not only won several hearts but also landed him with the Italian silver medal of bravery. Ernest called his war experience “the next best thing to getting killed and reading your own obituary.”

The Pangs of First Love

Soon after, while recuperating at a hospital in Italy, he fell in love with a nurse, Agnes von Kurowsky who was 7 years elder to him. Ernest felt that the most effective therapy for him was falling in love. His romance with Agnes led to the development of ‘A Very Short Story’ (first published as a vignette in 1924) and ‘A Farewell to Arms’(1929) which went on to become one of his greatest works.

Agnes and Ernest made for an attractive couple. She was cheerful, sympathetic and had a good sense of humour. He too was well built and had a charm about him that women so honestly fell for. Agnes voluntarily opted for a night duty at the hospital since it gave her enough time on hand to spend with Ernest.

However, their courtship was brief. Agnes thought Ernest did not know what he wanted. He was alcoholic and attracted to wealth. Though Ernest loved her with all his heart she thought he was immature and had not yet found his foot in the world. Even though Agnes wrote love letters to him describing her deep affection for him while she was away serving an influenza epidemic in Florence, she later jilted him for another man. She even claimed that, “she had never been in love with him.”

Contrastingly, as fate would have it, she did not end up marrying the lieutenant she left Ernest for. She later wrote to Ernest describing her fall-out.

This brief comradeship had a vast effect on Ernest. He became rather emotionally vulnerable and sought to seek revenge for the fact that Agnes ditched him for another man. However, Ernest did not do this in reality but by recreating Agnes as Catherine in A Farewell to Arms. In the novel, Catherine was portrayed as the hero’s mistress who is punished by death while giving birth to their child.

The Effect of War

Ernest returned home in 1919. War became the epitome of his learning. It made him outgrow the religious dogma and sentiments of Oak Park. His mental state saw a huge decline once he returned back from war.

The return of Ernest to his home in Oak Park was not only a physical process but majorly a transitional one. War had left him numb and simultaneously strong too. Life started to seem too mundane for this macho sportsman. He had lived life literally out of a suitcase, travelling to various lands. War, like it does to everyone else, made him highly pragmatic and mature. During this time, his relationship with his parents too seemed to strain. They could neither fathom their son’s overt maturity nor could they laud him for being such a vital part of war and exhibiting bravery. There was a constant urge from his father to pursue medicine. Ernest found their deliberate insistence to find a job and further his education to be too much of an affliction.

While still making do with an insurance amount of 1000 dollars for his war wounds, he lived at his parents’ house, reading and writing.

On one instance, he spoke at the Michigan Public Library where he met Harriet Connable, the wife of an executive at the Woolworth’s company who noticed the stark difference between Ernest and her son.

On her insistence, he took to train her son and later joined the ‘Toronto Star’ newspaper. It was while living at his friend’s house that Ernest met Elizabeth Hadley Richardson in early November 1920. Eight years older than Ernest, Hadley was tall, beautiful, and talented. Ernest expressed his love for her with boyish charm. The duo got married on 3rd September, 1921 and moved to Paris where Ernest was supposed to work as the European correspondent of the Toronto Star.

The Parisian Life

On 8th December, 1921, the couple moved into their humble apartment at, 74 rue Cardinal Lemoine. Though the house did not have even running water, yet, Hadley never raised her voice against such primal conditions in spite of having lived in comparative splendour.

Ernest was attracted to the Latin civilization of Italy, Spain and France. These were places that were more bohemian than the elementary Oak Park and he felt he could relive his war adventures here. His travelling sojourns often reflected themselves in his works. Conversely, he even became fluent in French, Spanish and Italian.

The influence of Ernest’s parents on him clearly replicated itself in his marriage. Ernest ensured that Hadley watched the six-day bike races all night, even though she didn’t really enjoy it. He also ascertained that she accompanied him on trips and adventures. Hadley once remarked saying, “I notice that in the Hemingway family you do what Ernest wants.”

Meanwhile, Ernest’s writing career had begun to shape up, having been introduced to some of the best writers of Paris, namely Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein and Sylvia Beach. Ernest and Pound saw admirers in each other. Both were devoted to everything artistic and hence enjoyed each other’s company. Ernest made a successful literary benchmark in Paris. His job with the Toronto Star weekly gave him freedom to travel and write. He worked there as a feature writer who interpreted events.

His first major assignment was the Genoa Economic Conference which allowed him to judge the post-war period and its leaders. He covered the Greco-Turkish War in October which witnessed the retreat of the Greek army and the Luassane conference in November. His poem “They all made peace-what is peace?” written after the conference focused on moral corruption in the international diplomacy arena. Hadley joined him in Luassane for a ski holiday in mid-December 1922. While travelling, she lost some of Ernest’s good stories and manuscripts about Kansas City. Ernest could not forgive her for it and thought she was careless and did not understand a writer’s life. This was a major blow to their marriage. Furthermore, he was in for a rude shock when he found out that Hadley was pregnant. He thought his freedom had been curbed with this unwanted pregnancy and he started seeing her as someone who would restrain his creative flurry.

Hadley’s pregnancy forced them to leave Europe and return to Toronto, as they felt that the medical facilities in North America were better than in Paris. The couple were bestowed with their first child, John Hadley Nicanor Ernest, nicknamed Bumpy, on 10th October, 1923.

Moulding of the Writer

In 1924, Ernest returned with his wife and son to France, where they lived at a flat above a noisy sawmill at 113 Notre Dame des Champs. Extremely primal in its ambience and amenities, the apartment did not have any gas or light, toilet or running water.

Ernest at the same time got the opportunity to edit ‘The Transatlantic Review’ on recommendation from Ezra Pound (an American expatriate poet and critic). Pound told Ford, another esteemed writer, “He’s an exceptional journalist. He writes very good verse and he’s the finest prose stylist in the world.”

In 1925, Ernest and Hadley joined a group of British and American expatriates and took a trip to the Festival of San Fernnin in Pamplona, Spain. It was during this time that Ernest produced some of his best works, namely ‘In Our Time’ and ‘The Sun Also Rises’. In Our Time, which also happened to be Ernest’s first novel was published in 1926. It was about an expatriate community travelling from Paris to Pamplona to watch the Spanish bullfights. The novelwas one of Ernest’s greatest works, examining the post-war disillusionment of his generation, artistically.

It was during these four years, from 1925 to 1929 that Ernest Hemingway produced some of his most amazing works. Though Ernest was short of funds, he realised that commercialism would only thwart his literary flurry. He said, “It is much more important to write for me in tranquillity, trying to write as well as I can, with no eye on any market, nor any thought of what the stuff will bring, or even if it can ever be published—than to fall into the money making trap which ruins American writers.”

As mentioned earlier, he was fiercely competitive. He considered writing too to be a competitive activity where all amateurs and masters fought the battle of the written word to outdo each other. He was heavily influenced by poets like Tolstoy, D.H. Lawrence, Stephen Crane and Conrad.

His non-fiction works namely ‘Death in the Afternoon’ and‘ The Green Hills of Africa’ also had tangential remarks. His writing was based on two principles: The first one was derived from his newspaper experience which moulded him to write based on real emotions and intellectual experiences by simultaneously being imaginative. He felt prose was the toughest to write. He said the most frightening thing he’d ever encountered was “A blank sheet of paper.” He felt, one had the entire gamut of words to put on it. Secondly, he rightly believed that a work of fiction could only be judged by what the author eliminated and the most essential gift for a writer was a “built-in, shock-proof shit detector” and that all great writers had it in them.

It led to his theory of the iceberg which was vastly appreciated and still sees appreciation. He believed that just as 7/8th of the iceberg remained under water and only 1/8th was seen, likewise, only the essentials should be seen in a story. Anything that does not require special mention should be eliminated. His writing had utmost clarity and he used very few similes and emphasized dialogues rather than narration.

On one hand where maestros like Lawrence and Scott Fitzgerald recognized Ernest Hemingway’s works as impeccable, his puritan family could barely fathom his literary streak. His father insisted he would rather see Ernest dead than right about sordid subjects. Grace too was of the same opinion and criticised his literary prowess.

Married Again

After the publication of The Sun Also Rises in 1926, Ernest divorced Hadley on 4th April,1927, to marry Pauline Pfeiffer, a writer based in Paris. Pauline came from a secure and prosperous background, with her parents based in Iowa. She was a pampered lady, stable and secure while Ernest was broke and alcoholic.

His rising popularity meant he wanted a new wife to match his status. Pauline was very Parisian in her dressing, personality, and tongue. He was attracted to Pauline’s exuberant living, having been bored with Hadley and an unwanted child. The notion that Hadley had exchanged the role of his wife to a mother after their child’s birth also pressed him to look for someone else. Pauline was good looking and matched Ernest’s wit. Simultaneously, Pauline was a devout catholic and Ernest too converted himself to one for her. His recent divorce with Hadley and conversion was not well accepted in Oak Park. Ernest and Pauline had a torrid affair and later got married in May 1927.

All this while, Ernest continued work on his book of short stories, ‘Men Without Women’. His works, ‘Cat in the Rain’, ‘Out of Season’, ‘A Canary for One’ were revelations of his marital woes.

Romanticizing Death

Pauline was now due to deliver. She decided on a hospital in Kansas City and gave birth to a son on 28th June, 1928. They named him Patrick and settled in Key West.

Key West, the southernmost town in America was described by Ernest as, “It’s the best place I’ve ever been anytime, anywhere, flowers, tamarind trees, guava trees, coconut palms...” A place like this made his creative juices flow.

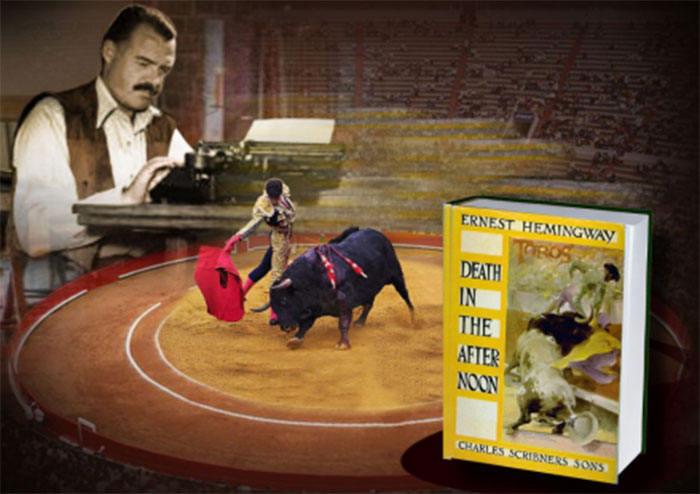

Meanwhile, Ernest received a telegram from his mother stating that his father had shot himself on account of loss of money in various real estate purchases, a prolonged illness, and depression. Despite personal struggles like these, Ernest continued with his passionate penning of his novel ‘A Farewell to Arms’, and completed it in January 1929. It was followed by an account on the bullfighting spectacle in Spain with Death in the Afternoon. An ardent observer of history, art, culture and sports, Ernest stated that,

“It is intended as an introduction to the modern Spanish bullfighting and attempts to explain that spectacle both emotionally and practically. It was written because there was no book which did this in Spanish or in English.”

Ernest always romanticized death and it was evident in this novel too, where the protagonist carries on with his duties while facing death, something described by Ernest as “grace under pressure”. However, critics didn’t take kindly to his gusty tone.

In the Public Eye

Ernest had begun to experience countless health problems like kidney pain, eye problems, throat infection and his heavy drinking nearly vacuumed him of his energy. However, he was big on hunting escapades at Cooke City, Montana, and felt it was the most beautiful place in the American West.

The Hemingways spent Christmas in Piggott and in January 1931 returned for their fourth winter in Key West where Pauline became pregnant, a second time around. Pauline expected to give birth to a girl but as fate would have it, she delivered a boy on 12th November, 1931. As a matter of fact, both, Pauline and Ernest resented children. Their son, Gregory, wasn’t breast fed and was taken care of by a nurse. Pauline was so much in love with Ernest that she devoted herself to her husband more than her children. She never gave a motherly embrace to her children. Pauline later remarked to Gregory, “Gig I just don’t have much of what’s called a maternal instinct I guess. I can’t stand horrid children until they are five or six.”

Meanwhile, Ernest continued with his routine of writing, sports and travel. After his father’s suicide, he started shouldering responsibilities and considered himself the head. It is here, that he started referring to himself as ‘Papa’. Ernest was not on good terms with his family members. He had called his father a coward in the open, blamed his mother for his father’s death, quarrelled with Marcelline, his sister, and condemned Carol, his youngest sister, for marrying the guy she liked.

Ernest Hemingway was a paradoxical figure. While on one side, he was a writer, on the other, he was a tough sportsman. While on one, he felt writing had to be pure, without being commercial, on the other he wanted luxury. He wrote of these contradictory aspects,

“I am naturally a happy guy, so I have a good time and I love my life and the ocean and my kids and writing and reading and all good painting along with bar life and responsibility and paying my bills and other mixed pleasures.”

Ernest often weaved the events of his life in his works and many a time exaggerated it. His inclination towards mythomania, the ability to myth events with facts, was necessary since he did not want to disappoint himself or his audience. He therefore interspersed imagination with reality.

Meanwhile, Scribners magazine paid Ernest a handsome $16000 for rights of A Farewell to Arms. It was banned in Boston on account of immoral language, but like they say, any publicity is good publicity and the critics praised it more than his earlier works. In 1933, the famous playwright T.S. Eliot dismissed the criticism that came to Ernest Hemingway and pointed that he wrote his real emotions.

The stage and film versions of A Farewell to Arms saw mediocre success. In spite of receiving $24000 for the film’s rights, Ernest did not like the film and stated that “the movie ruined everything…like talking about something good.”

The African Safari

In the summer of 1933, the Hemingway family and their Key West friend, Charles Thompson, journeyed to Africa for a safari which Ernest mentioned in The Green Hills of Africa. After much deliberation, he finally published it in 1935, which was a pseudo-non-fiction portrayal of his safari. As with his other tales, one could immediately see that Ernest was obsessed with heroism and bravery.

His African sojourn also provided materials for two of his stories, namely ‘The Snows of Kilimanjaro’and ‘The Short happy Life of Francis Macomber’ which portrayed the protagonist as weak, having being reduced to nothing due to his bouts of drinks, women and wealth. Much of the portrayal reflected Ernest’s thoughts about the women in his life. His fiction saw a greater reflection of the actual events than his non-fiction. For example, his World War I injuries more closely resembled to those of Frederic Henry, the protagonist in ‘A Farewell to Arms’.

The Spanish War

In 1936, Ernest reported for the North American Newspaper Alliance (NANA) on the Spanish Civil War where he supported the Republican government in several ways. He wrote nearly twenty-eight dispatches for NANA during the war period and later wrote his third major novel, ‘For Whom the Bell Tolls’, reporting from personal experiences of war.

Meanwhile, his second marriage too was nothing short of a conflict. Ernest had met a young writer, Martha Gellhorn, who covered the war for Time magazine. Their courtship lasted for four years after which Ernest divorced Pauline on 4th November, 1940, and three weeks later, got married to Martha. After returning from Spain, Martha and Ernest moved to ‘Fincia Vigia’, a farm house east of Havana, Cuba.

For Whom the Bell Tolls was on its way to becoming Ernest’s immaculate and most commercially successful novel. Using his experiences in war, he described the story of Robert Jordan, an American teacher who fought for the loyalists during the war.

In early 1941, Martha made her way to cover the war between China and Japan (part of World War II), where she took Ernest along. In spite of her reputation as an established war correspondent, Ernest was clearly more popular and stole the show when they went for reporting. The fact that they belonged to the same field often pitted them as competitors. Jealousy and an unhealthy competition crept in, due to which the two divorced on 21st December, 1945, thus making it the least successful of Ernest’s marriages. However, his fall-out with Martha was the most traumatic. He felt no one other than Agnes had jilted him so much. He had deeply loved the enchanting and high-spirited Martha, and thought she was the only one among his wives who was his equal in intellect and wit.

Ernest simply saw Martha for the last time when he left for America and passed via London. When he arrived in London, he met Mary welsh, who was a correspondent for Time magazine. He later became infatuated with her and married her on 14th March, 1946.

World War II and After

Meanwhile, the World War II was shaping up. Ernest became the de-facto leader to a small militia group outside of Paris. World War II historian Paul Fussell remarks, “Ernest got into considerable trouble playing infantry captain to a group of resistance people that he gathered because a correspondent is not supposed to lead troops, even if he does it well.”

Next he travelled to the north of France to join his friend General Buck Lanham to watch the war when the forces moved towards Germany. His sojourn there gave inspiration to ‘Across the river and Into the Trees.’ Although critics slammed the book, Ernest was adamant on gaining his stature.

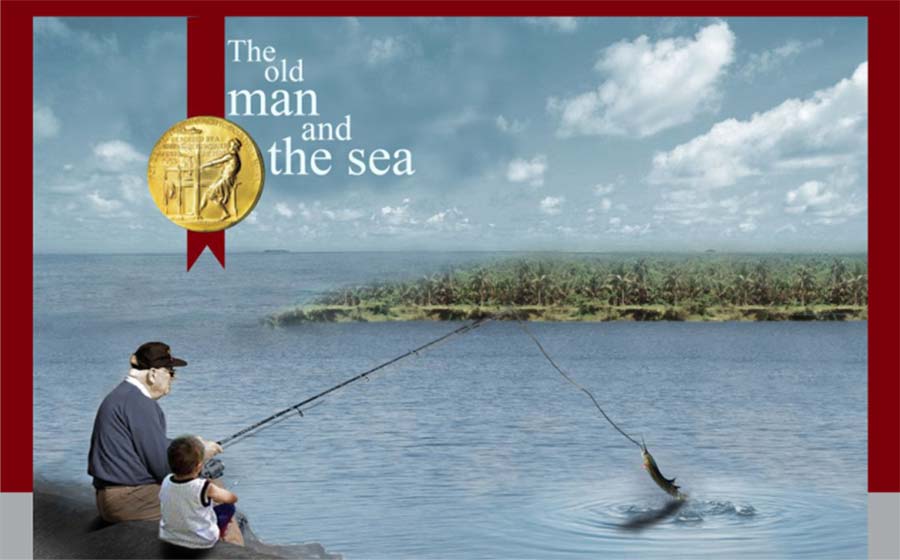

Finally, it was ‘The Old Man and the Sea’ that raised him to a pioneering position. It was a story about an old man, Santiago who fished alone in the Gulf Stream. Having gone without a catch for eighty-four days, he was feeling extremely dejected. For the first 40 days, a boy accompanied the old man. Later, the boy’s parents asked him to leave the old man, since he was salao or unlucky. Finally, he finds a marlin on the eighty-fifth day. It further described the battle between the fish and the old man.

The Old Man and the Sea was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1953. It was unanimously voted as the best novel for the Pulitzer Prize and was described by many as a masterpiece. It was the biggest seller in American fiction as of 1953 and immediately made it to the bestsellers list. The Columbia University however barred it for unknown political reasons.

African Plane Crash

In 1953, Ernest and Mary boarded a small private plane to take a tour of Africa and its scenic beauty. However, they were in for some major trouble as in mid-air the plane was hit by a telegraphic wire. The plane was badly damaged and made a crash landing. Ernest suffered some minor injuries then. On another flight to Uganda, a similar incident occurred again, but this time the injuries were graver.

The Hemingway’s decide to visit Venice before heading back to Cuba. On 28th October, 1954, Ernest Hemingway won the Nobel Prize for Literature for The Old Man and the Sea but was unable to attend it due to his injuries. The Nobel Prize was worth $ 36000 and the winner got a gold medal and an illuminated diploma as well. Meanwhile, the first hardcover edition of 50,000 copies of The Old Man and the Seawas published and Ernest made a good fortune.

The Descent

After a fallow decade in the 1940s, which saw unfinished works like ‘Garden of Eden’ and ‘Across the River’, Ernest Hemingway wrote a great deal in the 1950s. However this time around, his work was much inferior. ‘Islands in the stream’ and‘African Journal’ were all futile attempts.

In March 1952, Ernest described the deaths in the family that had depressed him beyond repair (maybe an explanation for his failed novels). The death of his mother Grace, of his former wife Pauline, the suicide of his maid servant and even the death of his first grand-son in Berlin had been key events shaping up his mental blasphemy. Not much is known regarding these deaths and in fact, many of the deaths came in the forefront only after Ernest mentioned about them. As a result of these tragic events, he did not feel as vigorous as before, he thought his creativity was seeing a downfall and remained disappointed with the fact that he could not write with the same zest. Nevertheless, he took a second safari between 1953 and 1954 and tried to recapture Spain and Africa in his words.

On having revived some manuscripts from his previous trip, Ernest started working on them. The resultant work, ‘A Moveable Feast’ was posthumously published in 1964. At the same time deteriorating health and a lifetime of heavy drinking had nearly eaten him up. In addition to all his physical illnesses, Ernest increasingly had paranoid fears of poverty and dissertation, inability to work and had increasingly turned suicidal.

In late July 1960, Ernest left Cuba and went to Ketchum, Idaho where the couple had purchased a flat a year ago. For Ernest, Idaho was the perfect retreat from the high-profile life he had lived until now. Sadly, the scenic surroundings of Idaho did little to improve his health.

In the fall of 1960, Ernest flew to Rochester, Minnesota and was admitted to the Mayo Clinic for high blood pressure. His suicidal tendencies had increased and his wife Mary could not handle it anymore. Ernest soon started receiving electric shocks in a bid to repair his mental plight. It resulted in memory loss and hence greater depression since the written word did not flow easily now.

The Final Shot

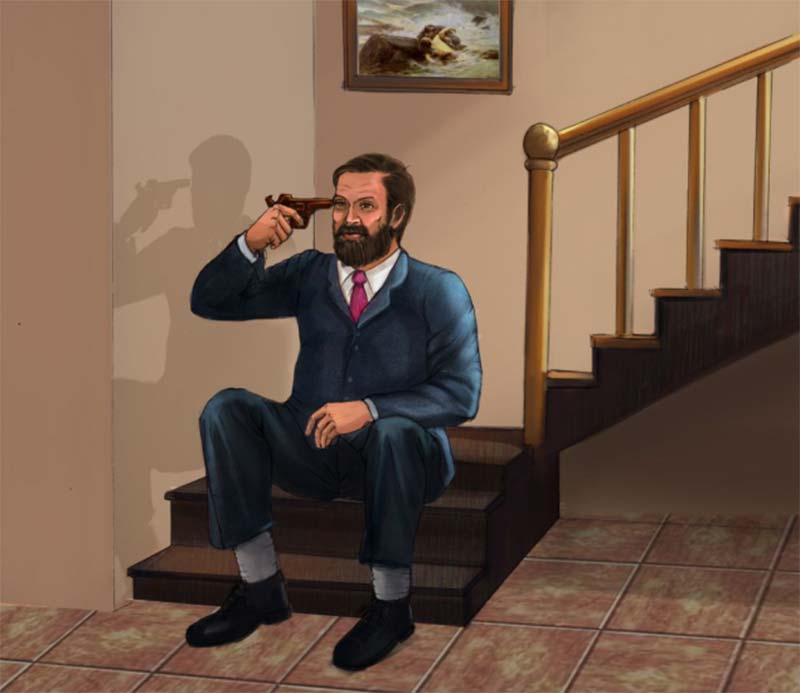

At the Mayo Clinic, Ernest had told Janet Flanner, a fellow writer, “liberty could be as important in the act of dying as in the acts of living”. In the end, he had consumed himself with what was a theme prevalent in his works, “death”. A terrible combination of physical and mental illness ultimately led him to drive his suicide.

Ernest had always condemned his father for his cowardly suicide, but when he personally underwent similar agony, he understood why his father had taken the drastic step. At about seven in the morning on 2nd July, 1961, Ernest Hemingway went to the basement, took a gun, went upstairs in the foyer, pulled the trigger, and shot himself dead. He received a funeral service at the graveside but not in the church. He had a catholic burial but did not get a High Mass, on account of being ostracized after divorcing Pauline and hence was denied the privilege of the complete funeral mass.

In spite of his being no more, Ernest Hemingway’s stoic themes, simplistic dialogues and unsentimental style continue to inspire authors around the world over even today. He was a man who lived his life with courage and who advised the world to “foot it bravely, strong and weary”. A man who created indelible memories with his literary prowess! A man who inspired the world to follow the “Heming-Way and how!”

Courage, brother, do not stumble,

Though thy path be dark as ight;

There’s a star to guide the humble:

Trust in God and do the right.

Let the road be rough and dreary,

And its end far out of sight,

Foot it bravely; strong or weary,

Trust in God, trust in God,

Trust in God and do the right.

Next Biography

Related Events And Inventions