Introduction

The mind is its own place, and in itself

Can make a Heav'n of Hell, a Hell of Heav'n.

-Paradise Lost, Book 1, John Milton

When a famous film actor was asked at an early stage in his career, why does he not try for Hollywood films instead of sticking to Bollywood, he replied, “It is better to reign in hell than to serve in heaven.” I was young and naive then and very impressed by the quote. I rushed to my mom to tell her about it and to brag about the actor’s intellectual prowess. My mom laughed and corrected me saying "That quote is written by John Milton, also known as Blind Milton in his poem, Paradise Lost."

Paradise Lost, a poem written 150 years ago, which remains widely popular even today because of its evergreen subject and spectacular visualization. One would not be exaggerating if they said that Paradise Lost is the greatest English poem ever to be conceived...and it was written by John Milton.

Milton’s life is even more intriguing than his work. For a man, who knew by the age of 20 that he wanted to be a poet, he did not write a single poem in the prime of his life as he felt that one should sacrifice their personal ambition for the greater good of the nation, which is what he ultimately did.

All of us want to achieve things in our life, but are we steadfast and resolute towards our goal? Milton lost his eyesight at the age of 44 due to excessive writing that he had to do as a government servant. He was completely blind and had to count on others for his everyday tasks. By that time, he had not even started writing the epic poem, which was the sole ambition in his life. In spite of all this, Paradise Lost remains for all to see, the triumphant victory of man over his adversities.

“A good book is the precious life-blood of a master-spirit,

embalmed and treasured up on purpose to a life beyond life.”

-John Milton.

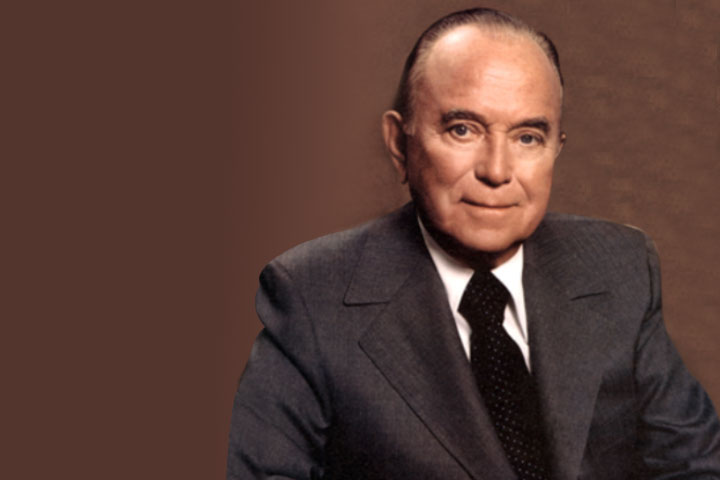

Not only was Milton an English poet, prose polemicist but also a civil servant for the English Commonwealth. He is also famous for Areopagitica, a powerful essay reproving censorship. Even though Milton’s works were highly disapproved by critics like T.S.Eliot and F.R.Leavis during the 20th Century, he still stood tall with several societies and intellectual journals as a study in his bag. Milton’s reputation as a poet, till date, still stands strong as ever.

The Birth of a Genius

John Milton was born on 9th December, 1608, to senior John Milton and Sarah Jeffery at a house in Bread Street, Cheapside, in London. He was the third of six children, only three of whom survived infancy

His father, John Milton, Sr., was an avid music composer and a man of great refinement and character, and his mother was known for her charities.

Milton spent the first sixteen years of his life in London. He grew up in an environment that was filled with greenery and abundance of nature. Milton often exchanged the weariness of his studies and the noise of the streets for a walk among the open fields that were very close to his house in London at that time.

The greatest influence in the poet's childhood was that of his father Sr. John Milton who was a remarkable man. He believed in following his own convictions and philosophies and in doing so, converted himself from a Roman Catholic to a Protestant, which resulted in him getting boycotted by his father. He then came to London and prospered as a modern solicitor, so much so, that in 1632, he was able to retire and live comfortably in the countryside.

Milton's early education was in grammar schools and by private tutors. He went for schooling to a non-conformist in Essex. At the age of 10, Milton was a well-nurtured and obedient boy. After leaving his Essex pedagogue, Milton took up private tuition from Thomas Young, a Scotchman from St. Andrews who first taught Milton to write Latin verse. It is interesting to note that all of Milton's early poems were in Latin. Milton was one of the only English poets whose mastery over Latin was as good as the Romans, or even better.

By 1620, at the age of 12, Milton was admitted to St. Paul's school. Even though the headmaster of this school was known to deliver quite a whipping, Milton threw himself into the studious life of the school and escaped this tyranny. In his own words, Milton says, “From the twelfth year of my age, I scarcely went from my lessons to bed before midnight.” Reports say that his father “ordered the maid to sit up for him.” Other than the books in the school curriculum, Milton also read voraciously outside the curriculum and practiced the Latin verse diligently. Before leaving St. Paul's, Milton had become well versed in three different languages other than English: French, Italian and Hebrew. Here, at the age of 15, Milton wrote two English productions that were paraphrases of Psalms.

One of the main incidents of Milton's schooling at St. Paul's was his memorable, first, and most tender friendship with Charles Dioadati. Diodati was an Italian and he influenced Milton's love for the Italian literature among other things. We can say that Charles Diodati was probably the only close friend Milton ever had.

"The Lady of Christ's" enters Cambridge

On 12th February , 1625, Milton enrolled at Christ's College, Cambridge where he stayed for the next seven years to procure his Master's degree in Arts (in those days, attainment of the degree of Master of Arts required seven years residence). Milton's intention, at this age, was to become a priest soon after the completion of his degree. Within a year's residence, however, Milton was asked to leave Cambridge due to a scuffle with his tutor William Chappell, for a fault that was not completely his. It is rumoured that Milton was whipped by his tutor. The fact that Milton was falsely accused is clearly understood because the university supported Milton and let him continue his course with a new tutor within a year.

In his seven years in Cambridge, it comes as no surprise that Milton was above the ordinary undergraduate. Wood, who was Milton's contemporary, says of Milton, that while at Cambridge he was “esteemed to be a virtuous and sober person yet not to be ignorant of his own parts.”

Due to his well-mannered, extremely virtuous nature, along with a fair complexion, short stature and great personal beauty, Milton was referred to as "The Lady of Christ's" by his fellow mates. This was clearly a form of ridicule that Milton did not take lightly. The title of "Lady" was conferred on him as a form of amusement and a practical joke. Milton contemptuously asked his friends:

“Was manhood only reserved for those who could chug large amounts of beer down their throats or even the peasants whose hands were rough from working with the plough all day.”

Milton was an extremely serious and mature boy, always conscious of life's great issues, and always uplifted with the noblest sort of ambition. As is the case with most men who are serious, focussed and virtuous, Milton was not very popular among his colleagues.

Milton was a man who was as severe with others as he was with himself when it came to virtuousness. Milton says:—

“He who would not be frustrate of his hope to write well hereafter in laudable things ought himself to be a true poem, that is, a composition and pattern of the best and honourablest things, not presuming to sing high praises of heroic men or famous cities, unless he have within himself the experience and practice of all that is praiseworthy.”

Indeed, that was what Milton was striving for, to be truthful and consistent in his character so that this candour may reflect in his poetry as well.

Inspite of not being so popular at the university, Milton was pleasantly surprised when a great crowd thronged to hear one of his speeches in the summer of 1628, nine months before his graduation.

The crowd consisted of everyone ranging from the experienced doctors to the amateur undergraduates with whom Milton was in contact almost every day. Milton says that “nearly the whole flower of the university” was present. It was clear, as made in a statement later by Milton's nephew, that when Milton left Cambridge in 1632, he was already “loved and admired by the whole university, particularly by the Fellows and most ingenious persons of his House.” We clearly see here that even though Milton was not popular as a person, his writings and his words had already found a great fan following. His genius was beginning to be known. Before he left Cambridge, Milton had written several poems, which we still read in his works: ‘On the Death of a Fair Infant’, ‘Ode on the Nativity’, ‘Song on May Morning’ and ‘Epitaph on the Marchioness of Winchester’.

At the end of his education in Cambridge (1625-1632), Milton was offered a teaching position in the university, which he refused. This was the time when the university was under a strict control of the clerks.

Milton strongly disapproved of this university system. So, at the end of seven years, Milton decided to leave Cambridge and pursue other interests. He also lost interest in the priesthood as he disapproved of the Church's discipline. In fact, Milton disapproved discipline in any form. Milton felt that a priest should have the freedom of a prophet, which was clearly not the case because of the excessive control being exercised by the Church. Milton did not want to “subscribe slave” and take oaths that he could not keep.

All these actions did not go down well with Milton's colleagues. They admonished him saying that he was being selfish in not returning as a teacher to share what he had leant from the university, and was aimless in his approach to life. Milton replied:—

“Why should not all the hopes that forward youth and vanity are afledge with, together with gain, pride, and ambition, call me forward more powerfully than a poor, regardless, and unprofitable sin of curiosity should be able to withhold? And what of the ‘desire of honour and repute and immortal fame seated in the breast of every true scholar?’ ”

On his twenty-third birthday, Milton wrote a beautiful autobiographical poem as a reply to one of his well wishers who questioned his decisions:—

“How soon hath Time, the subtle thief of youth,

Stolen on his wing my three- and-twentieth year!

My hasting days fly on with full career;

But my late spring no bud or blossom shew'th.

Perhaps my semblance might deceive the truth,

That I to manhood am arrived so near;

And inward ripeness doth much less appear,

Than some more timely-happy spirits indu'th.

Yet be it less or more, or soon or slow,

It shall be still in strictest measure even

To that same lot, however mean or high,

Towards which Time leads me, and the Will of Heaven.

All is if I have grace to use it so,

As ever in my great Taskmaster's eye.”

Milton had decided that he wanted to be a poet but felt that there was still so much literature left to be read and learnt.

Milton in Horton

“You ask what I am about, what I am thinking of, why, with God's help, of immortality.”

Milton spent the next six years of his life at his home in Horton, Buckinghamshire, in complete solidarity, immersed in the great works of literature and poetry.

We may be sure that he read the classics of all the languages that he understood. He lived as a recluse, forgetting the world outside and forgotten by it. The only recorded departure from his house was when he needed to buy books from London or to learn, “anything new in Mathematics or in Music, in which sciences I then delighted.”Milton wrote to his friend Diodati, “no delay, no rest, no care or thought almost about anything holds me aside until I reach the end I am making for…”

Milton's father, as any normal father, was not happy about Milton whiling away his time in labour that seemed to bear no immediate fruit. He reproached Milton and asked to take up something more lucrative and think about having a career in something other than poetry. He assured Milton that poetry was not going to pay the bills and warned him of the dangers of poverty. Milton wrote a poem to his father in Latin, Ad Patrem. In this poem, he asked his father:—

“How can you being a musician yourself, be against the career of your son as a poet? Isn't all art a form of the divine? Is poetry different from music? And it is you who taught me to place learning above everything else. You asked me to immerse myself in my studies instead of spending time in the City or the Bar. I am your creation. You inspired these great ideals in me. Now, you cannot ask me to make money the object of my life because you never taught me that. I have made a noble choice, to be a poet, and I know that at heart you agree with me and share it.”

After this poem, no one questioned Milton's right to be a poet.

Milton's six years at Horton can be said to be the happiest period of his life. Milton's father now supported him wholeheartedly in his aim to become a poet. Although Milton was not earning a single penny, yet, due to his father's financial and emotional support he could spend his time in Horton without any dependence or insecurity. Milton expressed his gratitude towards his father saying, “I will not praise thee for thy fulfillment of the ordinary duties of a parent, my debt is heavier. Thou hast neither made me a merchant nor a barrister.”

In this phase of his life, Milton led a solitary intellectual life, alone with his great ambition to become a poet. There was neither a sweetheart nor a friend, nor was Milton roaming around the literary cliques and the urban circles. Milton said to Diodati, “I am letting my wings grow and preparing to fly, but my Pegasus has not yet feathers enough to soar aloft in the fields of air.”

During his stay in Horton, Milton simply studied and was only occasionally a poet. It was as if, he was piling up wood at the altar conscious of his power to call down the fire of poetry when he willed to do so. It has been said about Milton that one of the most characteristic traits of Milton's genius was the dependence of his writing on a trigger from the external environment.

Except for the death of his mother on 3rd April , 1637, Milton's life during his residence at Horton is known to us entirely through his writings. These comprise of: A Sonnet to the Nightingale, L'Allegro, Il Penseroso, all probably written in 1633; Arcades, probably, and Comus, certainly, written in 1634; and Lycidas in 1637.

In A Sonnet to the Nightingale, Milton combined the ideal of Cambridge with that of Horton. This poem talked in praise of “plain living and high thinking” and about living among the charm of nature along with the refinement of culture.

Horton, the place where Milton was staying during that time, inspired L’Allegro and Il Penseroso. These two poems maybe regarded as one poem, whose theme was the praise of the reasonable life. Horton was a place that was rich and teeming with natural beauty and vast greenery in the form of open fields. In these poems, Milton touched the rural life and rural scenes with a freshness and directness that were never equalled by him in the later years. Another interesting thing about these six years is that they are the only period of Milton's life that he spent in the countryside.

Both, Arcades and Comus, were written for the famous musician Henry Lawes. These poems were performed for the family of the Earl of Bridgewater. Arcades was exhibited in 1634 to honour the mother-in-law of the Earl of Bridgewater. Milton's verses were one of the main features of the ample entertainment designed in her honour. They were an instant hit and Milton was requested to write one more poem for another occasion. This occasion was the celebration of Lord Bridgewater's assumption of the Lord Presidency of the Welsh Marches, hence, Comus was born in October 1633.

Comus, the richest fruit of Milton’s early genius, was a reflection of Milton's state of mind of the age at which he wrote it. The poem spoke about a scholar and idealist whose never ending enthusiasm is about to die due to too much worrying about pleasing the masses. No dramatist apart from Shakespeare has given to the world so many familiar quotations:

“Comus”

Nay, Lady, sit; if I but wave this wand,

Your nerves are all chained up in alabaster,

And you a statue, or, as Daphne was,

Root-bound, that fled Apollo.

“Lady”

Fool, do not boast.

Thou can'st not touch the freedom of my mind

With all thy charms, although this corporal rind

Thou hast immanacled, while Heaven sees good."

“Justina”

Thought is not in my power, but action is.

I will not move my foot to follow thee.

“Demon”

But a far mightier wisdom than thine own

Exerts itself within thee, with such power

Compelling thee to that which it inclines

That it shall force thy step: how wilt thou then

Resist, Justina?

“Justina”

By my free will.

“Demon”

I

Must force thy will.

“Justina”

It is invincible,

It were not free if thou hadst in this power upon it.

This masque (a dramatic enactment of the poem) was performed on Michaelmas night (the feast of Saint Michael the Archangel) in 1634 at the Ludlow castle, in Shropshire.

Milton did not acknowledge this poem with his own name during the time of its publishing, as he was of the mindset that publication was a very premature thing to do. So, this work was published by Lawes as the work done by an anonymous author. Lawes wrote an apology prefixed to the poem in the publication:—“Although not openly acknowledged by the author it is a legitimate offspring, so lovely and so much desired that the often copying of it hath tired my pen to give my several friends satisfaction, and brought me to a necessity of producing it to the public view.”

On receiving a printed copy from Lawes, one of the critics wrote:— “I should much commend the tragical part if the lyrical did not ravish me with a certain Dorique delicacy in your songs and odes, whereunto I must plainly confess to have seen yet nothing parallel in our language.”

Comus, once off his mind, Milton showed no inclination towards writing a poem for the next three years until the death of his friend, Edward King. Edward King died on 10th August, 1637, at sea due to unskilled seamanship. He was a batch mate of Milton from his Cambridge days who had left on a voyage to Ireland in the stillest summer weather. Suddenly, the vessel struck on a rock, foundered, and all on board perished, except a few who escaped in a boat. It was reported about King that he sacrificed his life for the sake of others. He is reported to have sunk into the sea with his hands folded in prayer. ‘Lycidas’ was Milton's eulogy for his dear colleague:—

“Fame is the spur that the clear spirit doth raise,

(That last infirmity of noble mind)

To scorn delights, and live laborious days;

But the fair guerdon when we hope to find,

And think to burst out into sudden blaze,

Comes the blind Fury with the abhorred shears,

And slits the thin-spun life. 'But not the praise,'

Phoebus replied, and touched my trembling ears;

'Fame is no plant that grows on mortal soil,

Nor in the glistering foil

Set off to the world, nor in broad rumour lies;

But lives and spreads aloft by those pure eyes,

And perfect witness of all-judging Jove;

As he pronounces lastly on each deed,

much fame in heaven expect thy meed.'”

One of the critics wrote about Lycidas:—“In Lycidas, we have reached the high-water mark of English Poetry and of Milton's own production.”

The poems of these years in Horton are the most delightful of Milton's poems. Even if he were not to write another poem ever in his life, he had given himself a place among the greatest poets of England. At the end of his stay at Horton, Milton wrote to his friend Diodati:—“You ask what I am about, what I am thinking of, why, with God's help, of immortality.” It was the voice of a man who knows he has already done great things but counts them as nothing compared with what he is to do later.

A Tour of the World

In 1637, Milton was planning to write his epic poem that would maybe take its place among the finest poems ever written. But, in reality, Milton wrote less poetry in the next 20 years than he had written in the previous five: less in quantity and far less in quality and importance.

The first interruption was his grand tour in April 1638. His generous father, who was well – to – do rather than rich, sponsored Milton's tour, which enabled him to go abroad for a year or two in comfortable style along with the services of a servant. Milton arrived in Paris in the spring of 1638. He spent a few days here entertained by the Swedish ambassador at that time, Grotius, and the English ambassador, Lord Scudamore.

In probably August or September, Milton arrived at Florence where he was enthusiastically welcomed by the literary circles and academic clubs. Some of the writers there were familiar with few of Milton's early works and praised him a great deal. They also praised England and criticized the prevailing economic and social conditions in Italy at that time. On 16th September, 1638, it was recorded in the minutes of the meetings of one of the literary clubs that “John Milton, an Englishman, read to the members a Latin hexameter poem showing great learning.” However, Milton spoke about the excessive praise he received in Italy and their thoughts about England thus:—

“I have sat among their learned men and been counted happy to be born in such a place of philosophic freedom as they supposed England was, while they themselves did nothing but bemoan the servile condition into which learning amongst them was brought, that this was it which had damped the glory of Italian wits; that nothing had been written there now these many years but flattery and fustian.”

The most important event in Milton's visit to Italy was his meeting with the famous Italian physicist, mathematician, astronomer and philosopher Galileo Galilei. Galileo was the saving grace of Italy at a time when the free spirit that Italy stood for was crushed, but not conquered, just like Galileo.

Galileo had just been released from imprisonment at Arcetri, and had been placed under house arrest. It was an impossible event that a protestant, Milton, would be allowed to meet Galileo during that time by the Roman Inquisition. However, one day when Galileo returned to his villa, there stood before him John Milton. The two great blind men of their century met. Neither did Galileo know at that point of time that his name would be mentioned in Paradise Lost, Milton's masterpiece that he wrote in his later years, nor Milton knew that within the next thirteen years, he too would be completely blind like Galileo. The calamity of blindness that crippled the astronomer restored inspiration to the poet. This meeting with Galileo made an everlasting impression on Milton that can be clearly seen from the fact that in his epic poem, Paradise Lost, Milton compared Satan's shield to the moon enlarged in “the Tuscan artist's optic glass”.

Next, Milton visited Rome. Here, he spent two months in the study of what remained of the ancient city. Milton was well received in Rome as well by several of her most distinguished scholars who paid him compliments typical of the Italian extravagance.

It can be said that music always had a greater attraction for Milton than plastic art. In Rome, Milton attended a magnificent concert given by Cardinal Barberini, who in Milton's words, “himself waiting at the doors, and seeking me out in so great a crowd, almost laying hold of me by the hand, admitted me within in a truly most honourable manner.” In this concert, Milton heard the famous singer and composer Leonara Baroni to whom he inscribed three Latin epigrams. Milton also studied a lot of antiquity during his time in Rome.

Next stop was Naples. Here Milton made the acquaintance of Giovanni Manso, a wealthy patron of the arts. Giovanni had supported both Tasso and Marini, who were considered to be two of the greatest poets of Italy. In Naples, Giovanni became Milton's escort. Later, Milton wrote Giovanni a Latin poem thanking him for his kindness. In the poem, Milton also spoke openly of his own poetic ambitions and said that if he lives to write this great poem on King Arthur, which he was then planning, he may consider living under Giovanni's patronage like the great Italian poet Tasso had done in the past.

Milton then intended to visit Greece but abandoned his plans as he thought it "base" to be “travelling abroad at case for intellectual culture while his fellow-countrymen were fighting at home for liberty.” This was the time when entire England was unhappy with the rule of King Charles I and a mutiny was expected anytime soon.

Milton was a protestant; he never made an attempt to hide his religious identity even though most of Italy was under the rule of Roman Inquisition, which essentially meant Roman Catholics. Milton said, “ had made this resolution with myself, not of my own accord to introduce conversation about religion; but, if interrogated respecting the faith, whatsoever I should suffer, to dissemble nothing.”

By February, Milton was again at Florence in Italy. After spending two months in Florence, Milton then visited Bologna, Ferrara and finally, Venice. After Venice, Milton visited Geneva where he received the shock of his life when he went visiting Diodati’s uncle, who also stayed there. The latter gave Milton the devastating news of Diodati's death and his burial in Blackfriars on August 27, 1638. This news completely shattered Milton, as Diodati was his closest friend. A traumatized Milton immediately set sail for England, his native soil, at the end of July 1939.

Politics Enters Milton—A poet Without Poetry

“I resolved, though I was then meditating certain other matters,

to transfer into this struggle all my genius and all strength of my industry.”

As soon as Milton reached home, a funeral tribute to his friend Diodati was the most important thing on his mind. Also, his brother-in-law had been dead for eight years leaving behind two sons. Milton's sister (who had remarried since then) now thought that it would be best for her sons to be educated by their uncle. So, along with his two nephews aged 8 and 9, Milton for the first time moved into a home of his own.

As soon as the settlement was over, Milton wrote, ‘Epitaphium Damonis’— the funeral tribute to his friend, Diodati. In this Latin poem, Milton expressed grief on the loss of the only true friend he really had. He also wrote about losing him at a time when he had so much to share with him about his trips abroad and his grand aspirations as a poet. All this was expressed with earnest emotion in truth and tenderness.

Finding the present house to be insufficient, Milton soon moved into a new house, which had a garden and was generally more spacious than the previous one:—

“I looked about to see if I could get any place that would hold myself and my books, and so I took a house of sufficient size in the city; and there with no small delight I resumed my intermittent studies; cheerfully leaving the event of public affairs, first to God, and then to whom the people had committed that task.”

Milton was now more than ever inclined to start the writing of his epic poem. He was considering various subjects for the same, slowly settling on a biblical one, on that of the Fall of Man. He did not contemplate mixing actively in political or religious controversy. However, in November 1640 occurred an event that governed Milton's life for the next twenty years – ‘The Long Parliament met’. Milton concerned about the republican cause and being a strong backer of freedom supported the parliament. From that moment on, politics became the dominant interest of Milton's life. A man who had stayed away from politics for the first thirty years of his life felt that his nation needed him. When the Long Parliament met, Milton wrote:-

“Perceiving that the true way to liberty followed from these beginnings, in as much also I had so prepared myself from my youth that, above all things, I could not be ignorant what is of Divine and what of human right, I resolved, though I was then meditating certain other matters, to transfer into this struggle all my genius and all strength of my industry.”

Milton's first works of this nature were five pamphlets written in 1641 and 1642 wherein he wrote about his views on the Church Government. Here, Milton fiercely demanded the abolition of Episcopacy (Government of a church by bishops) and the Establishment of a Presbyterian system (four governing bodies direct the work of the church: the session, presbytery, synod and General Assembly) in England:—

“Thou, therefore, that sittest in light and glory unapproachable. Parent of angels and men! Next, Thee I implore, Omnipotent King, redeemer of that lost remnant whose nature Thou didst assume, ineffable and everlasting Love! And Thou, the third subsistence of Divine Infinitude, illuminating Spirit, the joy and solace of created things! One Tri-personal godhead! Look upon this thy poor and almost spent and expiring Church, leave her not thus a prey to these importunate wolves, that wait and think long till they devour thy tender flock; these wild boars that have broken into thy vineyard, and left the print of their polluting hoofs on the souls of thy servants. O let them not bring about their damned designs that stand now at the entrance of the bottomless pit, expecting the watchword to open and let out those dreadful locusts and scorpions to reinvolve us in that pitchy cloud of infernal darkness, where we shall never more see the sun of thy truth again, never hope for the cheerful dawn, never more hear the bird of morning sing. Be moved with pity at the afflicted state of this our shaken monarchy, that now lies labouring under her throes, and struggling against the grudges of more dreaded calamities.”

For the next twenty years, Milton's notes proved that he not only stopped thinking about themes for poems but practically ceased to be a poet. This was Milton's age of Prose where he wrote only political agenda. His attitude throughout was that of an angry citizen who was unhappy with the political scenario existing at that time.

As works of prose-poetry, the world has never seen such works of passion written with such grandeur and poise. However, as far as logic goes—and meeting of the purpose for which they were written, these pamphlets were utter failures. The arguments written in these pamphlets were exceedingly weak. The views Milton advocated in these pamphlets did not prevail.

Next was Milton's treatise on divorce, but we will discuss that when we talk about Milton's relationships in these years.

Milton's tract on education was written as a reply and criticism of Samuel Hartlib's treatise on educational reform. Hartlib, a German-British polymath, in his treatise felt that the educational system prevailing at the time placed too much importance on written work and very less on the practical aspect of things, instilling among the students knowledge of words than knowledge of things. Milton's view was the exact opposite of Hartlib's. He felt that all the knowledge that a person could possibly need could to a very great extent be derived from books. Milton's treatise was highly impractical. It would overload the young mind with more information than what it could possibly digest. In addition, Milton extensively included classical works in his curriculum which were highly outdated. The greatest fault with Milton's treatise on education was that it was written for the Miltons of the world. It would be impossible for a normal person to follow his curriculum. From a hundred students, it was beyond the abilities of ninety nine and one of them would probably die from the strain that it would cause, such was the impracticality and absence of logic in this treatise.

Milton wrote the treatise for the ideal student without consideration for all, and that was its failure. As a work of prose, it serves for a beautiful reading but served no practical purpose. Again, Milton's idealistic views clashed with the practical aspect of things to produce a dunce.

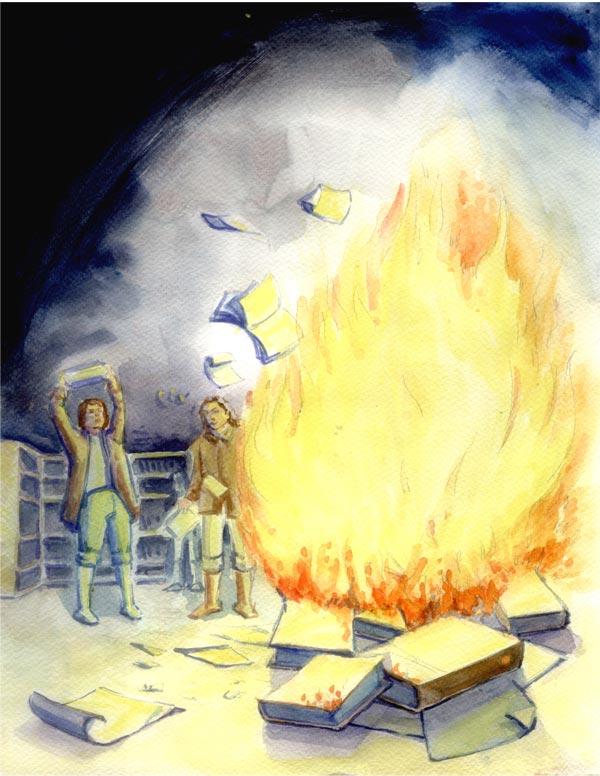

The Long Parliament had made it a rule in 1643 that all written works must be licensed (censored) by a panel appointed by them. Milton had never licensed any of his works and felt that it was blasphemy to ask an artist to agree to censorship. ‘Areopagitica; a Speech for the Liberty of Unlicensed Printing’ appeared in 1644, itself unlicensed. This is the only prose work of Milton whose topic was not obsolete. It was also composed with more care and art than others. Unlike his other works until now, this one saw Milton taking a practical stand and draw logical arguments. In Areopagitica Milton talked about how censorship does not prevent the circulation of bad books but is a grievous hindrance to the good ones; that it destroys the sense of independence and responsibility essential for fruitful literature.

Areopagitica is Milton’s best work in prose. Nothing written by him in prose is better known than the passage beginning, “Me thinks I see in my mind a noble and puissant nation”; and none of them contains so many valuable thoughts like “Revolution of ages do not oft recover the loss of a rejected truth”, “A dram of well-doing should be preferred before many time as much the forcible hindrance of evil doing. For God more esteems the growth and completing of one virtuous person than the restraint of ten vicious.”, “Opinion in good men is but knowledge in making” and “A man maybe a heretic in truth”. At the end again, Milton the poet, painted a beautiful picture with his pen where he imagined a world where all are prophets:—

“Behold now this vast city, a city of refuge, the mansion house of liberty, encompassed and surrounded with His protection; the shop of war hath not there more anvils and hammers working to fashion out the plates and instruments of armed justice in defence of beleaguered truth, than there be pens and heads there, sitting by their studious lamps, musing, searching, revolving new notions and ideas wherewith to present, as with their homage and their fealty, the approaching reformation.”

Milton's treatise on divorce

Milton was a romantic at heart. In the year 1632, he had written the poem, A Sonnet to the Nightingale, in which he spoke about his earnest desire to fall in love and how he would devoutly keep his commitment once in a relationship:—

“Young, gentle-natured, and a simple wooer,

Since from myself I stand in doubt to fly,

Lady, to thee my heart's poor gift, would I

Offer devoutly; and by tokens sure

I know it faithful, fearless, constant, pure,

In its conceptions graceful, good, and high.”

In the spring of 1643, Milton travelled to Oxfordshire on an errand. A certain Mr. Powell owed Milton's father a certain sum of money for which he was paying interest. Milton's errand was collecting that interest. However, like a bolt from the blue, Milton came back a married man!

The Civil War had erupted in England, making it a difficult time for everyone. Powell was also affected. Powell's daughter, Mary Powell, who was only 17 at that time, got married to Milton who was twice her age. The circumstances of this wedding are unknown. Whether Powell's daughter agreed to marry Milton for waiving of the interest, or it was love at first sight, or Milton was forced into the wedding can all be just speculations.

The only fact we know is that Milton came back home with a bride of 17, much to the surprise of his nephews and housekeeper.

Milton's home and lifestyle was the exact opposite of what Mary had led so far in her life. It was a studious household that was quiet and reflective whereas she was used to the jovial and fun atmosphere of her home. So, it comes as no surprise that after a month, she made a request to Milton to let her go and spend some time with her parents. Milton granted her request. However, Mary went and did not return. In the words of Milton's nephew, Phillip, who was living with him:—

“ By that time she had for a month, or thereabouts, led a philosophical life (after having been used to a great house, and much company and joviality), her friends, possibly incited by her own desire, made earnest suite by letter to have her company the remaining part of the summer, which was granted, on condition of her return at the time appointed, Michaelmas or thereabout. Michaelmas being come, and no news of his wife's return, he sent for her by letter, and receiving no answer sent several other letters, which were also unanswered, so that at last he dispatched down a foot-messenger; but the messenger came back without an answer. He thought it would be dishonourable ever to receive her again after such a repulse, and accordingly wrote two treatises.”

Milton was heartbroken by Mary's sudden leaving. At other times, maybe people would write songs about such things but during Milton's time, pamphlets were the order of the day. Milton's ‘Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce’, in its first edition, was a short and hasty composition that stemmed from his bitterness towards Mary. When she refused to return, Milton wrote the second edition.

Milton's treatise on divorce, like all his other pamphlets was a dismal failure. There were three reasons for this: it was blind to a woman's perspective, it lacked proper arguments, and was loaded with practical difficulties. He argued, that as law gives relief to a man whose wife disappoints him by not fulfilling his physical needs, so should be the case when she does not fulfil his mental and emotional needs. In addition to this, he did not give the wife any corresponding right to get rid of her husband. Milton's, “He for God only, she for God in him,” quote clearly highlights his wrong understanding of a woman's relation with her husband and towards God. Also, it is interesting to note that though Milton talked about not finding a suitable intellectual female companion, there is not a single mention about the education of girls on his treatise on education.

After the departure of his wife, Milton's father came to stay with him. Milton also accepted few boys as pupils. For the next two years, Milton continued to work on his treatise on divorce, producing newer editions. He also spent his time building arguments for the same. However, in the summer of 1645, Milton was openly wooing “a very handsome and witty gentlewoman, one of Dr. Davis' daughters.” She did not respond positively to his approaches. However, the rumours reached the Powells and a very interesting thing happened.

Milton was paying a usual visit to one of his relatives on a day in August 1645. There, he “was surprised to see one whom he thought to have never seen more, making submission and begging pardon on her knees before him.” This was indeed his wife, Mary Milton, begging Milton to take her back. Milton relented at first but then finally accepted her. Milton moved to a new house in Barbican to accommodate his now large family.

Soon after the relocation, Milton published the English and Latin poems written previously by him—only those that he thought were worthy of publication. This volume was published in January 1646.

The next three years were tough on Milton, both financially and emotionally. The Powells had a financial breakdown and moved in with Milton, as they had nowhere else to go. Father, son, several grandsons and daughters came to live in a house already full of pupils. Milton found this to be a great problem. He wrote to a friend, “Those whom the mere necessity of neighbourhood, or something else of a useless kind, has closely conjoined with me, whether by accident or the tie of law, they are the persons who sit daily in my company, weary me, nay, by heaven, almost plague me to death whenever they are jointly in the humour for it.”

Mary Milton gave birth to a daughter, Anne, on 29th July, 1646. In January 1647, Mr Powell died leaving his affairs in dire confusion. Two months later, Milton's father also passed away at the age of 84. Milton gave up his pupils and moved to a smaller house due to financial limitations. The Powells also moved to a separate house. Milton says of this period, “No one, ever saw me going about, no one ever saw me asking anything among my friends, or stationed at ten doors of the Court with a petitioner's face. I kept myself almost entirely at home, managing on my own resources, though in this civil tumult they were in great part kept from me, and contriving, though burdened with taxes in the main rather oppressive, to lead my frugal life.”

Milton did not do any major writing in this period and paid more attention to his personal life. Soon, on 25th October, 1648, Mary Milton gave birth to another baby girl, Mary.

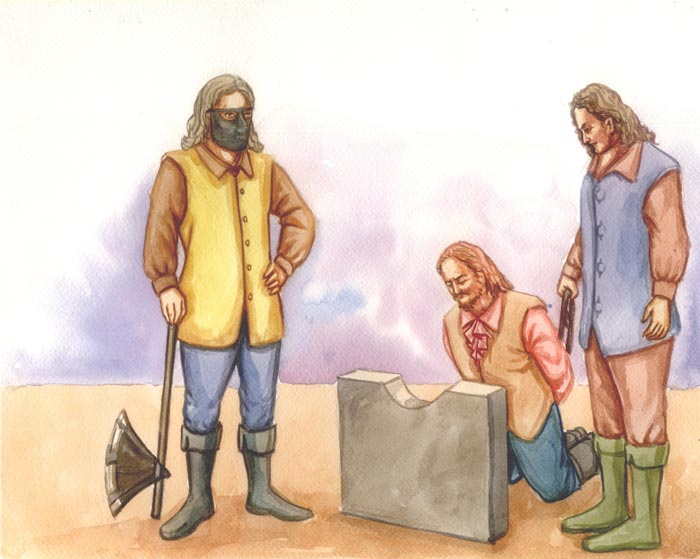

On 30th January, 1649, King Charles I was executed and a parliamentary and military rule was set up in England under the name Commonwealth of England led by Lord Olivier Cromwell.

On 13th February, a pamphlet was published by Milton called Tenure of Kings and Magistrates. In this pamphlet, Milton justified the proceedings of the army without any hesitation or compromise. He wrote, that just like any normal man the King too is liable to punishment and trails if he has committed a crime:—

“The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates proving that it is lawful, and hath been held so through all ages, for any who have the power to call to account a tyrant or wicked king, and after due conviction to depose and put him to death: if the ordinary magistrate have neglected or denied to do it.”

Obviously, Milton's statement “any who have the power” can bring the King to justice did not go well with the masses, but the Commonwealth loved it as it vindicated the King's execution. Immediately, Milton was appointed as the Secretary for Foreign Tongues to the Council of State on 15th March, 1649. He was paid a handsome salary and provided with a lavish accommodation at the Whitehall Palace.

Blindness embraces Milton

Milton's pen was now writing for the government. His first major task was to respond to Eikon Basilike, the manifesto published by the Royalists in 1649, praising the executed King Charles I and his deeds. Milton did not have a choice:—“I take it on me as a work assigned, rather than by me chosen or affected.” Milton toiled on this task though it did not interest him. It was his opinion that the King had already paid a price for his misdeeds by losing his head and further probing was unnecessary. However, within a few months, Milton's Eikonoklastes was published as a harsh reply to Eikon Basilike. Milton's reply had only three editions as compared to the fifty editions of Eikon Basilike.

Immediately, Charles II, son of King Charles I, commissioned one of the greatest Latin scholars of that time, Salmasius, to write against the Commonwealth. His book ‘Defensio Regia pro Carolo I’ appeared in October or November, 1649 and on 8th January, 1650, it was ordered by the Council of State “that Mr. Milton do prepare something in answer to the Book of Salmasius, and when he hath done it bring it to the Council.” By now, Milton had started experiencing problems with his eyesight. He had already lost the vision in one eye and doctors had warned him that if he strained his eyes, he would lose the vision in both his eyes and become blind. In spite of this, Milton calmly accepted the task of writing the reply.

Milton spent a year in preparing his reply which came out in the beginning of 1651. His work, Pro Populo Anglicano Defensio is not held in high regard by Milton's present day followers. In this work, Milton hurled words such as “blockhead”, “liar” and “apostate” on Charles I, and still more upon Salmasius. In those days these were considered no lesser than abuses. It showed that even when it came to using foul language to make a point, Milton was second to no one. Milton was lauded for his courage. His book was that of true passion that crushed all of Salmasius’ claims. The book, published in or about 1651 instantly won over European opinion and was considered a better literary work than that of Salmasius’. Milton became a celebrity. Every distinguished foreigner, then resident in London, either called him to congratulate or paid him a casual visit. The Queen herself told Salmasius that Milton had won this literary war. However, Milton had paid a heavy price for this, about which he wrote:

“What supports me, dost thou ask?

The conscience, friend, to have lost them overplied

In liberty's defence, my noble task,

O! Which all Europe rings from side to side;

This thought might lead me through world's vain mask,

Content though blind, had I no better guide.”

By March 1652, at the age of 44, Milton was completely blind. He wrote:-

“The choice lay before me between dereliction of a supreme duty and loss of eyesight; in such a case I could not listen to the physician, not if Aesculapius himself had spoken from his sanctuary; I could not but obey that inward monitor, I know not what, that spoke to me from heaven.”

Milton could hear the praise for his work ringing across whole of Europe, but he could not see it. One of Milton's friends recommended to him an occult artist who he felt might have the cure to his blindness. Milton wrote back to the friend:—

“Whatever ray of hope may be for me from your famous physician, all the same, as in a case quite incurable, I prepare and compose myself accordingly. My darkness, hitherto, by the singular kindness of God, amid rest and studies, and the voices and greetings of friends, has been much easier to bear than that of a deathly one. But if, as is written, 'Man doth not live by bread alone, but by every word that proceedeth out of the mouth of God,' what should prevent me from resting in the belief that eyesight lies not in eyes alone, but enough for all purposes in God's leading and providence? Verily, while only He looks out for me, and provides for me, as He doth; teaching me and leading me forth with His hand through my whole life, I shall willingly, since it hath seemed good to Him, have given my eyes their long holiday. And to you I now bid farewell, with a mind not less brave and steadfast than if I were Lynceus himself for keenness of sight.”

Such was Milton's faith in God and in himself, that in 1951, he appended a motto to his signature: “I am made perfect in weakness."

Milton's loss of sight was accompanied by domestic sorrow. His wife died after giving birth to their third daughter Deborah, in May 1652. The responsibility of bringing up three young daughters was now solely on the shoulders of a blind Milton.

Since the writing of Pro Populo Anglicano Defensio, Milton was involved in the thick of a controversy that lasted till 1655. Replies came out both to his Eikonoklastes and to his Defensio. Milton's nephew wrote on his behalf and friends of Salmasius on his. The adversaries did not spare Milton's character just as he had not spared theirs. As a result, ‘Defensio Secunda’ was written by Milton himself and came out in 1654. The final reply to this chapter came in 1655 after which the controversy died.

The Fall of a nation

The Commonwealth was crumbling. The same events that brought down Charles I were being committed by their leader Cromwell too. Milton stood by his dying party. Even though Milton had written against censorship in his work Areopagitica, as the Secretary of the Commonwealth his work included censoring books that the party thought were against their interests. Though Milton had blamed Charles I for dissolving the parliament and taking things in his own hands in the Tenure of Kings, here was Cromwell doing the same thing but now Milton was supporting the very same acts he had then strongly objected. We can confidently say that Milton's understanding of politics was very dismal.

Even though the house was disintegrating, Milton was busy painting the insides. He wrote exalting speeches that were given by Cromwell. As the Secretary, it was Milton's job to write letters in Latin aiding correspondence between Britain and the other countries. These letters are found in great number and are known for their quantity rather than their quality. Milton wrote a sonnet in 1655 due to the immense grief felt by him, and the atrocious massacre of protestants by the Duke of Savoy:

“Avenge, O Lord, thy slaughtered saints, whose bones

Lie scattered on the Alpine mountains cold;

Even them who kept thy truth so pure of old,

When all our fathers worshipped stocks and stones.

Forget not: in thy book record their groans

Who were thy sheep, and in their ancient fold

Slain by the bloody Piemontese that rolled

Mother with infant down the rocks. Their moans

The vales redoubled to the hills, and they

To Heaven. Their martyred blood and ashes sow

O'er all the Italian fields, where still doth sway

The triple tyrant; that from these may grow

A hundredfold, who, having learned thy way,

Early may fly the Babylonian woe.”

In April 1655, Milton's salary was greatly reduced and his payment became like a retiring pension. However, in these last months of the Commonwealth, Milton was more active than ever. He wrote eleven official letters between September 1658 and February 1659. In May 1659, Milton bade goodbye to the Civil Service and also wrote one of the greatest sonnets that the world has ever seen, ‘On His Blindness’ :—

“When I consider how my light is spent

Ere half my days in this dark world and wide,

And that one talent which is death to hide

Lodg'd with me useless, though my soul more bent

To serve therewith my Maker, and present

My true account, lest he returning chide,

"Doth God exact day-labour, light denied?"

I fondly ask. But Patience, to prevent

That murmur, soon replies: "God doth not need

Either man's work or his own gifts: who best

Bear his mild yoke, they serve him best. His state

Is kingly; thousands at his bidding speed

And post o'er land and ocean without rest:

They also serve who only stand and wait.”

In this sonnet, Milton is asking God, “How do you expect me to serve you now that you have taken my vision?” But then, a voice inside him (referred to as Patience) replies, “those who accept God's decisions, no matter what they are, serve Him best. His kingdoms are vast and innumerable are the people who serve Him, and even those who just stand and wait serve him no less.”

The principal domestic event in Milton's life, meanwhile, had been his marriage with Katherine, daughter of Captain Woodcock, in November 1656. However, both his newly married wife and his infant daughter died in February and March, 1658 respectively. It is probable that Milton spent hardly any time with his wife due to all the political turmoil of that time, but the time they spent were very loving and he considered her very dear to him. Milton writes of a dream, in which he dreamt that she was restored to him, and then he woke up to realize that she was no more. Milton completely ignored his daughters and his nephews. He would spend his time mostly with his friends from the party and a few of “enthusiastic young men who accounted it a privilege to read to him, or act as his amanuenses, or hear him talk.” Milton's heart belonged to these times when he was discussing poetry with his students. Nothing bolsters this fact more than this beautiful sonnet written by him regarding these times spent:—

“Lawrence, of virtuous father virtuous son,

Now that the fields are dank and ways are mire,

Where shall we sometimes meet, and by the fire

Help waste a sullen day, what may be won

From the hard season gaining? Time will run

On smoother, till Favonius reinspire

The frozen earth, and clothe in fresh attire

The lily and rose, that neither sow'd nor spun.

What neat repast shall feast us, light and choice,

Of Attic taste, with wine, whence we may rise

To hear the lute well touch'd, or artful voice

Warble immortal notes and Tuscan air?

He who of those delights can judge, and spare

To interpose them oft, is not unwise.”

From Bad to Worse for Milton

“I dark in light exposed

To daily fraud, contempt, abuse, and wrong”

The Commonwealth was dead and King Charles II was about to be restored. But Milton was oblivious to this fact and so was his party. In the February of 1659, Milton's ‘Treatise of Civil Power in Ecclesiastical Causes’

was published and in August a sequel, ‘Considerations on the likeliest means to remove Hirelings out of the Church’. In both these pamphlets, Milton talked about bringing in new Church reforms. Talking about Church reforms at a time like this when there were much more grave things that needed immediate attention was like trying to hang a frame on the walls of a house whose ceiling was collapsing.

In February 1660, the people had spoken and the unanimous cry was for restoration of Charles II. On the eve of the restoration, Milton protested even more loudly about the righteousness of the execution of Charles I. In the second edition of his pamphlet, ‘The Ready and Easy Way to establish a free Commonwealth’, he wrote that the family of Charles I f should be permanently excluded from the throne. We must keep in mind that this was the time when Charles II was just about to be crowned King. This act required great courage or utter foolishness and Milton faced the consequences. This pamphlet was published on 3rd March,1660 and immediately on 28th March,1660 the publisher was arrested. Milton went into hiding for the next few months. In May, Charles II regained the throne and immediately the hunt began for those who were considered to be the king’s enemies. There is no doubt that Milton's name was high on this list.

However, in August, while Milton was still in hiding, a rule of amnesty was passed, where except for a certain list of people, all other political offenders were to be vindicated of their charges as an enemy to the King. Milton's name was not on that list. This happened only because Milton had great friends and pupils who were at high positions in the newly formed parliament. They were the ones who hid Milton and also now saved him from death by hanging. But Milton was arrested nevertheless. There had been an order that all of Milton's books be burned and he be arrested and put in prison.

This was perhaps an action taken by Milton's friends to make sure that he got the amnesty.

Anyhow, Milton was arrested and put into the custody of the Sergeant-at-Arms. He was ordered to be released on December 15, 1660, but here a curious incident happened. The Sergeant-at-Arms demanded high fees from Milton. Milton, though he was so close to death in the hands of the hangman, did not lose his courage. He refused to pay the high fees. The Sergeant immediately said that Milton deserved to be hung. It was only due to the interference of his friends again that the fees was brought down and Milton escaped death. He relinquished his old house and moved into a temporary refuge. Milton's nerves were shaken. He was now also suffering from gout, which is a form of arthritis. Politically and physically, Milton was surrounded by darkness.

Milton's cause was lost, his ideals in the dust, his enemies victorious, his friends dead, or exiled, or imprisoned, his name infamous, his principles condemned, and his property seriously impaired by misfortune. Milton was deprived of his position as Latin Secretary even before the restoration and now, even the two thousand pounds that he had invested in government securities was fleeced from him. Another great sum was lost by his nephew Phillip due to some bad business decisions. In all, Milton was forced to live in an average income, far from the healthy finances that the son of a wealthy businessperson was used to. The saddest part of Milton’s life was his relation with his daughters. Milton's daughters despised him. They conspired to rob him and even sold some of his precious books to rag pickers.

Milton probably never realized though how greatly he himself was to be blamed for the circumstances with his daughters. In the first place, he neglected to educate them. His eldest daughter, Anne, could not even write her name. The second, Mary, and the third, Deborah, were better taught, but still not enough. Milton's views of the moral and intellectual inferiority of women made him a horrible father to three motherless girls. Plenty of young men were more than happy to read to Milton but they weren’t always available. The result is that his daughters were, as Phillip writes “condemned to the performance of reading and exactly pronouncing of all the languages of whatever book he should at one time or other fit to peruse; viz. The Hebrew (and, I think, the Syriac), the Greek, the Latin, the Italian, Spanish and French.” None of these languages were understood by Milton's daughters and neither did he bother to teach them. His attitude was, that one tongue was enough for a woman. Milton continually referred to his daughters as “unkind children”. When one of his daughters was told about Milton's third marriage, she is reported to have said “that was no news to hear of his wedding, but if she could hear of his death, that was something.” Milton writes about the state of affairs with his daughters in a later poem:—

“I dark in light exposed

To daily fraud, contempt, abuse, and wrong,

Within doors, or without, still as a fool

In power of others, never in my own.”

In February 1663, on the advice of his physician, Milton married for the third time. His wife was a distant relative of the physician himself and her name was Elizabeth Minshull. She was pretty, had golden hair and brought back happiness into Milton's life. She was thirty years younger to him. Nevertheless, just like Milton, she enjoyed music and could talk at length about art and other things that interested Milton. She is said to have sung to his accompaniment on the organ. This relation marked the end of sorrow for Milton.

Milton: The Eternal Poet

Finally, Milton now did what his sole ambition had been since the time he was a teenager- become a great poet. He was contemplating over a topic for the epic poem that he wanted to write for the past twenty years. The poem, which is his epic masterpiece, has been speculated to been completed by the year 1663. This masterwork was known as ‘Paradise Lost’-

The reason why the world knows him today as one of the greatest poets to have graced this planet.

In Paradise Lost, Milton described the fall of man from heaven by completely using his own imagination to create the visuals of heaven and hell. In this poem, Milton depicted the bloom of paradise with the same brush that depicted the flames and blackness of hell. He made Satan the devil, a heroic figure while preserving his central character showing him with sympathy and admiration. The speech given by Satan after he realizes that he has been banished in hell after his defeat in the hands of God is unlike anything that the English Literature has ever seen:—

“Is this the Region, this the Soil, the Clime,

Said then the lost Arch Angel, this the seat

That we must change for Heav'n, this mournful gloom

For that celestial light? Be it so, since hee

Who now is Sovran can dispose and bid

What shall be right: fardest from him is best

Whom reason hath equald, force hath made supream

Above his equals. Farewel happy Fields

Where Joy for ever dwells: Hail horrours, hail

Infernal world, and thou profoundest Hell

Receive thy new Possessor: One who brings

A mind not to be chang'd by Place or Time.

The mind is its own place, and in itself

Can make a Heav'n of Hell, a Hell of Heav'n.

What matter where, if I be still the same,

And what I should be, all but less then hee

Whom Thunder hath made greater? Here at least

We shall be free; th' Almighty hath not built

Here for his envy, will not drive us hence:

Here we may reign secure, and in my choice

To reign is worth ambition though in Hell:

Better to reign in Hell, then serve in Heav'n.”

He imagined how Adam, Eve, the angels, archangels and God himself would have spoken and gave them a character and form that required literary genius. Sublimity is the key feature of Paradise Lost. While reading the poem, we feel like pygmies transported to the world of giants.

There is nothing forced or affected in this compositional grandeur, no visible effort, everything proceeds with a severe and majestic order controlled by the pen of Milton. The similes and other poetical ornaments are sprinkled no more than that is demanded by the concept. The description of paradise and the story of Creation required great resources of knowledge. In his descriptions of Hell, Milton uses isolated images of awful majesty and in the description of Heaven; the universal landscape is bathed in a general atmosphere of lustrous splendour. No subject but a Biblical one would have insured Milton universal popularity among his countrymen. His style is that of an ancient classic transplanted, like Aladdin's palace set down with all its magnificence in the heart of Africa; and his diction, the delight of the educated, is the despair of the ignorant man.

One of the greatest charms of Paradise Lost is the incomparable metre (a poetic writing style using a rhythmic structure. This form was popularized by William Shakespeare), which remains without equal in the English for the combination of majesty and music. The organ-like solemnity of his verbal music is obtained partly by extreme attention to variety of pause, but chiefly, by the period, not the individual line, being made the metrical unit, “so that each line in a period shall carry its proper burden of sound, but the burden shall be differently distributed in the successive verses.” Hence, lines which taken singly seem almost un-metrical, in combination with their associates appear indispensable parts of the general harmony.

After a final revision in the year 1665, Paradise Lost was ready to be published. However, the negotiations for its publication were not complete until 27th April, 1667. Milton sold the copyrights of the book for five pounds. It was not a great sum but immortality was to follow which was a due compensation. Within a year and half of its publication, Paradise Lost sold over thirteen hundred copies. More than the money, the greatness of Milton was instantly acknowledged, thanks to the encouragement and great positive reviews of two of the most famous critics of that time, Dryden and Lord Dorset. Dryden said about Paradise Lost “This man cuts us all out and the ancients too.” Dryden also wanted to convert Milton's play into a "heroic opera". It was written about Paradise Lost that it is “one of the greatest, most noble and sublime which either this age or nation has produced.”

Milton gave a copy of Paradise Lost to one of his friends who commented, “Thou hast said much here of Paradise Lost, but what hast thou to say of paradise found?” In 1666, Milton presented his new poem ‘Paradise Regained’ to him saying “This is owing to you; for you put into my head by the question you put to me at Chalfont; which before I had not thought of.”

Though perfectly executed, still, Paradise Regained remains inferior to Paradise Lost when it comes to poetic excellence. Great poets have said that they would rather have written only the first two books of Paradise Lost than ten such poems as Paradise Regained. Blake, the great poet, says about Paradise Regained which was about angels and gods “The reason why Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of angels and God, and at liberty when of Devils and Hell, is because he was a true poet, and of the Devil's party without knowing it.”

Milton's next work Samson Agonistes, possibly written in the 1660’s, was a tragedy following the form of the Greek tragedies. This was essentially an old man's poems with respect to the author and the reader alike. There was much to repel and less to attract a young reader. It was no wonder that a young fellow from Cambridge placed this below Comus in taste. However, Samson's impression of the author can escape no one. Old, blind, captive, helpless, decried, miserable in the failure of all his ideals, upheld only by faith and his own unconquerable spirit, Milton is clearly the counterpart of his hero, the Satan.

After writing this poem, Gout started to affect Milton severely. Without it, he said, he could find blindness tolerable. Yet, even in this situation Milton continued to sing and be cheerful. In 1670, Milton thought it was wise for him to send his daughters away from him “to learn some curious and ingenious sorts of manufacture that are proper for women to learn, particularly embroideries in gold or silver” and other jobs by which they could make a living on their own. In these late years, Milton had many more friends and relatives coming and visiting him. These later years also produced several little publications that were Milton's earlier unpublished works. None of these were very significant. A more important work, though not as much as Milton's poems was ‘History of Britain’ in the year 1670.

Milton had won the battle of his life. The astonishing achievements of his last years had more than fulfilled the high ambition and proud words of his long distant youth. Literary history for seven continuous years from 1667 to 1674 saw a poet like Milton and his creative enterprise poetries. Milton's life's work was now finished, and finished with absolute success, just as he had hoped for. He had left nothing unwritten, nothing undone, nor was he ignorant of the fame he had received in these last years. In July 1674, Milton had started anticipating death. But about the middle of October, “he was very merry and seemed to be in good health of body.” However, early in November, “the gout stuck in,” and he died on November 8, late at night, “with so little pain that the time of his expiring was not perceived by those in the room.”

In spite of facing a hurricane of obstacles physically, emotionally and financially, the kind that most of us would probably shudder merely by the thought of, Milton rose against all odds to finish his epic poem at the age of fifty. It is uplifting to see the victorious completion of a great plan that is the life of Milton. Milton's poem, Paradise Lost, remains till date an exemplary statement for how the imagination of an artist can create a universe of its own in spite of the physical body being crippled in most senses. And Milton's life remains an outstanding example of how a strong man's will can so victoriously mould a world of adverse circumstances—anguish, defeat, even the threatening of shadow of death itself — to make them the very instruments by which he becomes that which he has, from the beginning of his life, chosen for himself to be.

Next Biography