“Now if I had attended Prodicus's fifty drachma course of lectures, after which, as he himself says, a man has a complete education on this subject, there would be nothing to hinder your learning the truth about the correctness of names at once; but I have heard only the one drachma course, and so I do not know what the truth is about such matters,” says Plato while narrating a joke by his teacher, Socrates. Known for his off-the-cuff remarks, Socrates was referring to Prodicus, his close friend and as believed by some historians, also his teacher.

Very little is known about Prodicus’ life but historians, based on his mention in various works by various thinkers presume he was born in or around 465BC in Ceos, now called Kea in modern Greece. Writings of other thinkers of his and later era indicate, Prodicus was apparently well educated, was a master of rhetoric and could debate on a variety of issues extempore.

Works of several writers testify that Prodicus travelled to Athens frequently, usually as the envoy of Ceos on the invitation of aristocrats and trade. During his stay in the Grecian capital, he would amuse himself by attending public lectures and debates by thinkers of various schools of thoughts. It is claimed, Prodicus became enamoured with Socratic teachings when the great thinker, famous for his eccentric mannerisms and “gadfly” or questioning one’s claimed depth of knowledge fascinated him immensely. Prodicus and Socrates soon became friends.

Socrates and Prodicus eschewed one-another’s teachings. Socrates was happy to welcome anyone to listen to his thoughts but Prodicus charged a stiff fee of 50 Drachmae or silver coins for a single lecture. While Socrates was content to live a life with basic needs and never craved for wealth, Prodicus, au contraire, loved to luxuriate at the expense of the rich and famous of Athens.

Yet, historians do not depict him as an avaricious thinker: It is perceived that since he was a businessman, he may have charged either to defray his costs of travel or make some extra profit. By any standards, his fee of 50 Drachmae was considered during the era as highly exorbitant.’

Prodicus had a rather boorish speech, possibly due to some earlier disease or injury. Despite this and his extortionate fees, he was a much sought speaker with people willing to cough up the sum and tolerate the peculiar diction. Socrates, despite being offered a seat to attend the lecture gratis, reportedly declined the largesse of Prodicus, in conformity to his own teaching that everyone is ignorant, that people pretend to possess knowledge and wisdom.

Prodicus died in 395BC- just four years before Socrates. The two friends shared something in common: Both were charged with impiety and instigating the youth of Athens. They were tried in Athenian courts and found guilty.

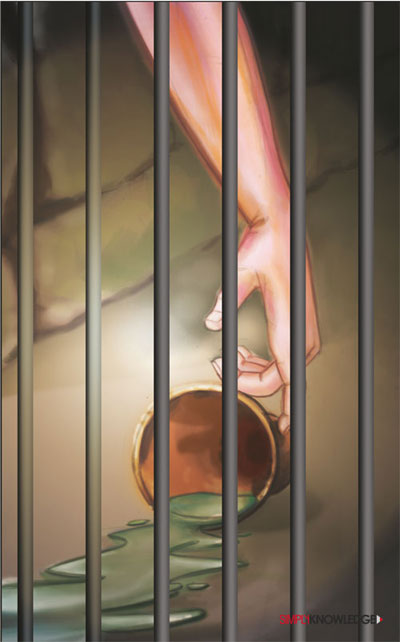

The coup de grace: Both were executed by a fatal dose of Hemlock- a potent herbal toxin that gradually benumbs the nervous system causing painless death. Prodicus was executed for his teachings in 395BC.

The life and teachings of Prodicus were not wasted. They gave rise to a new science and lesser known branch of psychology, oft used to appease egos of ancient royals and wealthy personae. His main teaching was the study of names- Onomastics.

Prodicus’ main axioms were proper pronunciation of words and especially, perplexing ancient Greek names. He believed, and rightly so, that people react positively when their names are pronounced properly and when each word is spoken with definitude. The reason: Names or identities are cherished by all. And to date, any one whose name is not pronounced properly can feel offended. More so with ancient Greek names, whose pronunciations were rather arduous for the uninitiated or people who arrived in Athens from various other parts of the empire and had strong dialects. Commoners, wishing to gain favours from nobles found the art of pronouncing names properly rather handy.

Archaic as it sounds, Prodicus’ technique was based on pure psychology: Pampering the already idolized aristocracy by showing feigned respect was considered the magic key to winning favours, including Athenian citizenship for aliens.

Onomastics is used to date, especially while addressing eminent personalities, religious figures, diplomats and official records where a wrong pronunciation can have serious legal implications. Some allowance is however made for genuine errors that may occur due to dialects or speech impairments.

Prodicus was the first to propound that humans created gods for their convenience. He propounded, humans revered natural objects and phenomenon such as moon, sun, rain, and the like, merely because they benefitted the mankind. He further elucidated his point by drawing a corollary between objects worthy of worship and those which were considered as having no religious significance, since their use was limited. The sun is essential for life, rain and water for irrigation of farms and orchards and moon to mark the calendar. Ancient Grecians made deities of these useful objects naming bread as a deity Demeter, wine as Dionysus, water as Poseidon and fire as Hephaistus These teachings grossly contravened popular beliefs of the era and earned him the dubious title as an atheist. These teachings led to Prodicus being charged of impiety and subsequent execution.

Though Prodicus was charged, tried and executed for impiety, his teachings on deities and ‘man made gods’ continue to be fiercely debated to date. Renowned scientist Charles Darwin, in his theories about evolution, tacitly denies the existence of a “divine hand” in creation of life and natural phenomenon on Earth. Various religions however explicitly claim that everything on this planet was created by god or gods.

Treatises written by Prodicus are largely extinct, save a few surviving fragments. Hence, theologians and philosophers are unable to discern lucidly whether the ancient thinker was an atheist or merely reviled the Grecian practice of attributing common items with divinity.

Next Biography