The Wright Brothers

The sight of an airplane enthralls one and all. Ripping through the sky at a speed of 600 Mph, the thunderous machines are a symbol of the astounding human intellect and the ability to think beyond the conventional boundaries and statistics. For centuries, mankind had aspired to fly like birds by defying gravity not just within the known world but to the unknown depths of the universe. And today, that dream is a reality. With over a million airplanes in the air every day, ferrying countless passengers around the globe, airplanes have become an indispensable part of today’s life. They are one of the most sophisticated machines to be ever designed by man.

But just over a century ago, even getting off the ground was unthinkable. Since time immemorial many great inventors struggled to solve the problem of sustained controlled flight. Experiment with flight had always been dangerous and numerous people lost their lives attempting the fatal feat. Until two bicycle makers came along at the beginning of the 20th century and changed the aviation history forever. They were Wilbur and Orville Wright of Dayton, Ohio in USA. Both were college dropouts and were fascinated by machines from the very beginning. They spent their years of youth, dismembering all kinds of machines, from toys to printing presses to bicycles. They were particularly influenced by bicycles – an unstable machine that could be controlled and balanced with practice, and they believed, that a similar theory could be applied to flying machines. Though they lacked the deep pockets or support from scientific institutions, they were thoroughbred engineers who would carefully test and re-test and painstakingly learn and re-learn until they got it right. And finally, on December 17, 1903 they got it right, when they built the world's first successful airplane. The Wright Brothers , as the world knows them, had created history and turned mankind’s greatest dream of flying into reality. This is their fascinating story.

The Birth of Wright Brothers

Wright Brothers were the sons of Milton and Susan Wright. Both Milton and Susan were remarkable people who always encouraged their children to take on intellectual challenges. Milton was a professor of theology and a minister in the Church of the United Brethren (a Christian denomination just like Roman Catholic Church). He later on became the Bishop of the United Brethren. On the other hand, Susan was the daughter of a simple carriage maker in Indiana and while women education was still uncommon in those days, Susan excelled in literature and science and was the top mathematician in her class. She was also excellent with tools and built household appliances and toys for her family. While Milton was a strict disciplinarian, Susan was warm, loving and protective. Susan, who had converted to the United Brethren faith when she was 14, met Milton at Hartville College, Indiana in 1853, where Milton was working and Susan was a student of literature. Both shared a love for learning and after a long courtship, Milton asked Susan to marry him and accompany him to the Oregon Territory. She did not go with him to Oregon, but agreed to marry on his return. They got married in 1859, when Milton was almost 31 and Susan, 28. They had seven children together. Wilbur was their third son and was born on 16th April, 1867near Millville, Indiana. He was a strong and active child who excelled in skating, gymnastics and making kites. He attended school when he was eight and his love for learning, complimented by a great memory, allowed him to excel as a student.. The Wright family moved to Dayton, Ohio in 1870 when Milton was chosen to edit the church newspaper, ‘The Religious Telescope’. This position also eventually got him elected as the bishop. Soon after they arrived, Susan gave birth to twins, Otis and Ida. Ida died after 13 days and Otis lived for only 18 days. Orville, the sixth child, and the other half of the famous Wright Brothers was born in Dayton on 19th August,1871. The youngest child Katherine, and the only surviving daughter, was born in Dayton in 1874, exactly three years after Orville. Interestingly, they shared the same birthday, August 19. From a very young age, Orville showed an interest in technology and science. He performed experiments and took things apart to find out how they worked. He attended the ‘Central High School’ in Dayton, Ohio and excelled in studies just like Wilbur. But while Wilbur was a quiet child, Orville was impulsive and energetic. When he was just ten, Orville started his very first business of making and selling kites. Thus, from a very young age Orville showed great zeal in working independently and building things that could fly.

In 1878, when their father gave Wilbur and Orville a new toy helicopter designed by Alphonse Pénaud, the famous French aeronautical pioneer, he laid the perfect foundation for them to initiate a splendid career in airplanes. Made of paper, bamboo, cork and powered by a rubber band, the foot long toy caught the fascination of both, Wilbur who was 11 and Orville, who was just 7. They played with it and even experimented with the design trying to improve it. They made several toy helicopters varying in size.

Little Orville wanted to make a bigger toy that could fly both him and Wilbur. But when they undertook to build the toy on a much larger scale it failed to work well. They wondered why, and it was to be only many years later that the Wright Brothers would find out the real reasons behind airplane stability. That little toy helicopter had certainly lit a huge fire in the hearts of the little Wrights. Meanwhile, Milton’s work as Bishop of the United Brethren Church meant that the family was always on the move, moving a total of 12 times before they finally settled in Dayton, Ohio in 1884. Perhaps because they moved around a great deal, the Wright siblings never developed long-lasting friendships with people outside the family circle and as a result, were very close to each other, especially the youngest, three, Wilbur, Orville and Katherine. They were so close to each other that sometime in their youth, the three vowed never to marry and always stay together. Thus, Wilbur and Orville grew in an environment that fostered good family values, hard work and a fervor to learn and think creatively.

A life put on hold

This conducive childhood turned Wilbur into a confident and intelligent young man who had a great future ahead of him. When he turned 18 in 1885, Wilbur was a top-notch student, an accomplished gymnast, and a good football player. He was all set to go to Yale College to complete his graduation. But destiny had other plans for him and his life completely changed with the blink of an eye. One day while playing ice hockey with his friends, he met with a serious accident. He was struck in the face by a flying hockey stick resulting in the loss of his front teeth.

Then, some two or three weeks later Wilbur suffered from palpitation of the heart which took a year to heal and prevented him from attending Yale. His life had suddenly taken a turn for the worse. He became withdrawn and spent the next few years largely housebound, reading extensively in his father’s library. During the same time another tragedy struck the family. Susan, their mother, was diagnosed with tuberculosis and this compelled Wilbur to completely abandon his plans of attending college. He decided to put his life on hold and made it his job to nurse his mother Susan.

However, his curiosity and affinity for learning remained unchanged. When he was not looking after his mother, he read voraciously. He would also assist his father in writing for the Brethren Church, and this is when he developed a penchant for writing. This seemingly tragic phase in Wilbur’s life drew his focus into reading and learning new things on his own.

The Print Business

While Wilbur spent time studying at home, Orville who was a good student initially, began to lose interest in studies and instead developed fondness for the print business. When he was just 15, he started his first newspaper “The Midget”(a school newspaper) with his friend Ed Sines. From 1887, Orville worked two summers as a printer's apprentice to learn the printing trade. Orville called upon his housebound elder brother Wilbur to assist him in building a reasonably professional press from a damaged tombstone, buggy parts, and other recycled odds and ends.

Thus, the long-lasting partnership between Wilbur and Orville began. People who saw them work together observed, that the two brothers would hardly converse while working on a task, almost as if they could read each other's minds. Then in 1889, after a prolonged fight against tuberculosis, their mother Susan breathed her last. The Wright household wobbled and this meant that Katherine, the youngest of the Wright siblings needed to step up and take charge of the household. She did that brilliantly by juggling chores and taking care of her family without ever giving up her studies. She was the only Wright sibling to complete her graduation. Her elder brother Orville on the other hand had decided not to return for his senior year of high school. Instead, he began printing his own newspaper, ‘The West Side News’. He enlisted his brother Wilbur as the editor.

The weekly publication received modest success and Orville soon changed it to a daily one and called it ‘The Evening Item’. However, they could not compete with the larger and more established daily newspapers and after a few months ‘The Evening Item’ folded and the brothers went back to being simple job printers. Although their first venture did not exactly flourish, Orville and Wilbur had come much closer now and were no longer just brothers, they became business partners. Orville drew Wilbur into the printing business, first, as a consultant on press construction and then as a writer, editor and fellow pressman. Their father Milton who had by then become the Bishop of the United Brethren Church, began to funnel some of the church’s printing contracts to his sons to help the fledgling enterprise. When the Wright printing firm landed a contract to print an editorial on the ‘United Brethren Church Commission’ in 1888, the cover page credited ‘Wright Bros., Job Printers’ as the publisher. It was the first time that the soon-to-be famous phrase, ‘Wright Brothers’ had appeared in print in reference to the team of Orville and Wilbur Wright. Slowly, the business grew and moved from the tiny carriage barn to a nearby office building on West Third Street. Sensing a need to grow further, Wilbur and Orville built a second, larger press capable of printing 500 to 1000 sheets an hour. Its unusual construction was ingenious enough to attract the attention of other professional printers.

The Bicycle Business

During the 1890s, America was swept by the bicycling craze. Everyone was riding one and so were Wilbur and Orville. In 1892, they bought the new ‘safety’ bicycles. Soon cycling, or wheeling as it was then called, became their shared passion. The invention of the safety bicycle, with two wheels of equal size, made the bicycle relatively easy to mount and ride.

Wilbur and Orville were savvy businessmen and so to cash in on the new rage and to supplement their income from the printing business, they opened a bicycle shop called the ‘Wright Cycle Exchange’in 1892. The brothers retained their printing business, but like good managers, left the day-to-day running of it to Ed Sines, Orville’s original partner in their first print business. In addition to repairing bicycles, they also sold new bikes and accessories. The cycle business was brisk, and in early 1893 they moved to larger quarters, and then later that same year they moved again and renamed the business ‘The Wright Cycle Company’. In a year's time, bicycles had become their primary business.

Their older brother Lorin, who was having a hard time making a living, was roped in by Wilbur and Orville to take over the print shop and work with Ed. While the three Wright siblings were busy in their cycle and print business, their sister Katherine, who had finished college at Oberlin began to work as a teacher at the ‘Steele High School’ in Dayton, Ohio.

After several years of repairing bicycles, the Wright Brothers realized that they could build their own better bicycles than what were available in the market. So in 1896, they began to manufacture two bicycle models of their own. One was the top-of-the line bicycle which they called the ‘Van Cleve’and the other one was the lowest-priced variation which they named as ‘St. Clair.’

These bicycles were never mass-produced machines, but were hand-built to a customer’s specification. They added a few original improvements, including an oil-retaining wheel hub and coaster brakes. They made approximately 300 bicycles between 1896 and 1900 and were earning $2000 to $3000 a year in gross sales from the bicycle business; quite a respectable income in those times.

But money was never their primary motivator. The Wright Brothers were driven by the sheer pleasure of learning new things. And now it was time to reignite their childhood passion of flying. There were enough developments now in the world of aviation to arouse Wilbur and Orville’s interest back towards their long forgotten dream.

The Aviation Age of Wright Brothers

When the Wright Brothers were inventing their own forms of the safety bicycle in 1896, the world of aviation was seeing a flurry of activity with numerous attempts to take the sky in balloons, gliders, ornithopters and other flying machines. However, the key problem crippling every experiment was the lack of control. These primitive flying machines relied heavily on the skills of the pilots to maintain the equilibrium of the aircraft. Many ended in disaster. But in the midst of laughable failures, there were three remarkable stories that caught the eye of Wilbur Wright. One of them was of the famous American physicist Dr. Samuel Pierpont Langley, who flew his steam powered Aerodrome No. 5, half a mile over the waters of the Potomac River on May 6, 1896. His successful experiment captured the imagination of many Americans. Dr. Langley was the Secretary of ‘The Smithsonian Institution’ (the American government’s research institute) and an accomplished astronomer. He made the first detailed observations of sunspots, invented the bolometer to measure electromagnetic radiation and vastly simplified the running of the world's railroads by creating ‘Standard time’ and time zones. He was also the most well-known scientist in America due to his campaign of lectures, newspaper stories and magazine articles to popularize general science. Ten years ago, he had become interested in aeronautics and had built a series of large flying models which he called ‘Aerodromes’. While Aerodrome number 0 to 4 failed to take-off, Langley found success with Aerodrome No. 5 in 1896, when it was catapulted over the Potomac River in Washington, DC. The craft flew for a minute and a half and made a second flight the same day tracing three lazy circles in the sky at altitudes up to 69 feet in about 90 seconds. Although it carried no pilot, it was the largest powered aircraft ever to make a sustained flight, up to that time. The Wrights followed this little accomplishment with great keenness, when tragic news from Europe shook the aviation world.

The Flying Man from Germany

On 9th August, 1896, the world of aviation witnessed the death of Otto Lilienthal (a German pioneer of aviation), popularly known as ‘The Flying Man’ from Germany. His glider got caught in the wind and crashed. Lilienthal was an inventor, engineer and manufacturer who along with his younger brother Gustav spent the decades of the 1870s and 1880s collecting information on aeronautics and performing experiments in aerodynamics. They built several gliders that had no aerodynamic controls and could be navigated only by shifting the pilot’s body weight. Before his death, Lilienthal had made over 2000 glides, some as long as 800 feet. He had also built two facilities for launching his gliders, a ‘flight station’ at Rhinow Hills and an artificial hill called ‘Fliegeberg’ (Flight Hill) near Lichterfelde, Berlin. These were the world's first airfields. With all this flying going on, Lilienthal's reputation grew. ‘The Flying Man’ was a common subject for newspapers and magazine articles all over the world. Great scientists came to visit him, including Samuel Langley and Octave Chanute. In 1894, he began to manufacture what he called his ‘Standard Glider’ and sold them to aspiring pilots in Europe and North America. He was flying this glider on 9th August, 1896 when he flew into a thermal, a burst of hot air, rising from the land beneath him. The gust turned up the nose of his aircraft sharply and Lilienthal kicked forward to bring it down again. But the glider did not react quickly enough. Lilienthal ran out of flying speed, the glider stalled, and Lilienthal plunged to his death from an altitude of 50 feet. His dying words were reported as "Sacrifices must be made." Due to this fatal accident many who believed in the possibility of manned flight were momentarily discouraged. Wilbur and Orville tracked Lilienthal’s work through newspaper and magazine articles and were inspired by his dramatic glides in Europe. Besides Langley and Lilienthal, the Wrights’ closely followed the work of Octave Chanute. In 1896, he gathered together several young aeronautical investigators, including Augustus Herring, to test fly several new glider designs in the sand dunes around Miller, Indiana. These experiments resulted in the ‘Chanute-Herring biplane glider’, the most successful glider of its time and served as a starting point for the Wright Brothers in their glorious accomplishments in aviation. The one common element that the Wrights’ deduced from the works of Langley, Lilienthal and Chanute was, that the gliders developed by them lacked control. As bicyclists, they had great respect for control and knew how important it was for a rider to maintain the equilibrium of the bicycle. Similarly, an aircraft would never be practical unless it could be balanced in the air and navigated by the flyer. At the outset of their experiments they regarded control as the unsolved third part of ‘the flying problem’, the first two being ‘suitable wing design’ and ‘a powerful engine’. The Wright Brothers, thus differed sharply from the more experienced practitioners of the day such as Langley who built powerful engines, attached them to airframes equipped with unproven control devices and expected to take to air with no previous flying experience. The Wright Brothers were determined to find something better. And they did make a breakthrough, thanks to their observant nature.

Enthused by Nature

Wilbur and Orville began observing the birds to understand the science of flight control.

They discovered that birds changed the angle of the ends of their wings to make their bodies roll right or left. The brothers decided that this could also be a good way for a flying machine to turn, to ‘bank’ or ‘lean’ into the turn.They puzzled over how to achieve the same with man-made wings and accidentally discovered wing-warping when Wilbur idly twisted a long inner-tube box in their bicycle shop. He happened to place his thumbs and forefingers on diagonal corners of the box. He noticed that when he squeezed his thumbs and forefingers together, the box twisted. The surfaces at each end rotated in opposite directions. In his mind, Wilbur imagined the same action with the ‘Chanute-Herring glider.’ The biplane was essentially a box with open sides. With a set of cables, he could twist the wings just as he twisted the box. When the tip of one wing was turned up, it increased the lift at that end. Where the other tip turned down, the lift would decrease. The difference in lift would cause the biplane to roll to the right or left and thus allow the flyer to control the glider.

Wilbur and Orville had painstakingly toyed with several ideas but nothing worked, until they came across this simple yet elegant solution. For them, it was a moment of emotional and intellectual satisfaction. But while they were taking baby steps in the field of aviation, things were not looking too bright for their bicycle company.

The Bicycle’s Decline

By 1897, the bicycle industry had reached its saturation point with an oversupply of cheap bicycles. The cost of buying a bicycle went from $100 to $10 and smaller players like The Wright Cycle Company could no longer compete with the mass producers.

In contrast to the shrinking bicycle industry, the Department of War awarded Dr. Samuel Langley a generous grant of $50,000 to build a manned version of his Aerodrome 5. It was the largest amount of money that the U.S. government had ever spent for weapon research and it also implied that a serious living could be made in aviation.

The Wrights’ had no doubt that Langley would produce a successful aircraft. He was, after all, the most famous scientist in America and had the requisite money and Smithsonian’s intellectual power for his support. But they also knew that Langley's aerodromes could not be navigated as they lacked any sort of controls. And that was where they could make a difference. The amount of public interest in Lilienthal and Chanute also suggested to them that flying could be another popular recreational sport like cycling. Many years later when Wilbur was demonstrating his flyer in Europe, a journalist asked him what was an airplane good for. Wilbur replied, "Why, for sport, of course."

The First Attempt

On 30th May, 1899, Wilbur wrote to the Smithsonian Institution asking for a list of publications on aeronautics. "I wish to avail myself of all that is already known," Wilbur wrote, "and then if possible add my mite to help on the future worker who will attain final success."

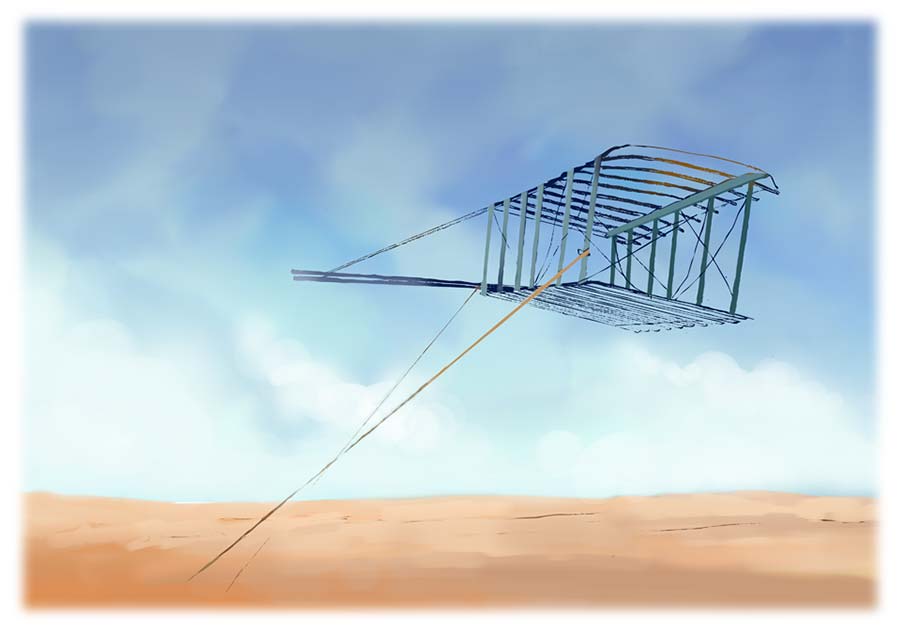

He received a list of works and four Smithsonian pamphlets on the subject of aerial navigation. Powered by the works of earlier aviators and their own learnings in their bicycle shop, Wilbur Wright constructed and tested a biplane kite in the July of 1899. The kite measured five feet from tip to tip and about 13 inches from front to rear, in which, wing-warping was achieved by manipulation of four cords leading to the ground. With the help of a dozen schoolboys, Wilbur carried out the successful kite experiment at a nearby open space at the Union Biblical Seminary. Later, several of schoolboys would remember that when Wilbur flew the kite, it swooped at them and they had to dive for cover. But aside from scaring the kids, the controls worked just as Wilbur had expected. His hypothesis on wing-warping had been proved right and this would later become an important aerodynamic design principle.

Orville was camping with his friends at the time of the kite experiment. Wilbur, who was too excited by the outcome of the successful flight, rode his bicycle out to the camp to share the good news with his brother. Immediately, the Wrights began to plan a glider with ‘wing-warping’ controls.

As Wilbur and Orville laboured over the design of their first glider in the autumn of 1899, they also began to search for a suitable sandy and windy location to carry out their flying experiments. Wilbur wrote to the U.S. Weather Bureau seeking details of the average winds in the Chicago area from August to September. He also wrote to Octave Chanute at his home in Chicago for advice, which was also the beginning of a long and fruitful correspondence between the prolific aviators. The Bureau replied with a list showing the average wind velocities in 150 cities throughout the United States. Sixth on this list was an out-of-the way place in North Carolina with vast stretches of sand and water, few trees and relatively high winds. It was called ‘Kitty Hawk.’

Kitty Hawk was a tiny village on the North Carolinian barrier islands just a few miles off the Atlantic shore and entirely made of sand. The Wrights zeroed in on this remote location as it was also closer to Dayton than the other places and the spot gave them privacy from reporters, who had turned the 1896 Chanute experiments at Lake Michigan into something of a circus.

1900 - The adventure at Kitty Hawk

On 13th September, 1900, Wilbur Wright arrived at Kitty Hawk after an arduous journey of over two days. Orville joined him three weeks later to begin their manned gliding experiments. The Wrights’ based their first glider on the Chanute-Herring Biplane hang glider

and used aeronautical data on lift which Lilienthal had published earlier. In October 1900, they carried out several tests by flying the glider like a kite, not far above the ground, with men below holding tether ropes. Some were unmanned flights with sandbags or chain. They even kited a local boy Tom Tate in one of the tests. They kept on modifying their glider design after each test. Wilbur did some testing himself but did not allow Orville to do any flying tests. He loved and cared for Orville too much to allow him to take the risky tests. The glider's lift was less than what they had liked but the brothers were encouraged because the craft's front elevator worked well and they had no accidents. However, the small number of free glides meant that they were not able to give the wing-warping a true test. On 23rd October, 1900 they decided to conclude their test and head back to Dayton.

1901 - The second outing at Kitty Hawk

The Wrights’ were eager to get back to Kitty Hawk and needed someone with technical skills to run operations at their bicycle company while they pursued their passion for flying. They hired Charlie Taylor to help them with their business. Charlie was a talented and experienced machinist and he took care of the repairs and sales in the absence of Orville and Wilbur.

The Wright Brothers returned to Kitty Hawk in July 1901 and spent several weeks building a new glider,

this time with more wing span of 22 feet, almost doubling the wing surface of the previous model to provide more lift. It was the largest glider ever flown and should have out-performed its predecessor, but that was not the case. It was non-responsive in the air and prone to stalling. Wilbur, who continued to do all the flying, weathered one harrowing accident after another. Fortunately, the glider could be made to ‘pancake’ or slide into the ground, when it lost flying speed instead of nosing over in the deadly dive that had killed Lilienthal. This saved Wilbur from serious injury, although he suffered numerous cuts and bruises.

Octave Chanute also visited the Kitty Hawk camp that summer and was impressed by what he saw. Although the 1901 glider fell far short of Orville and Wilbur’s expectations, Chanute saw it make a glide of 389 feet, outdistancing the flying machines he had tested in 1896. Chanute left Kitty Hawk on August 11 while the Wrights stayed for another few weeks, but the flying did not improve. In fact, it grew more dangerous. When using the wing-warping controls, they found that the glider exhibited a peculiar feeling of instability. It was slipping sideways through the air towards the set of wings that were on the inside of the turn. On one flight, when Wilbur warped the wings, the craft nosed down in a harrowing dive splitting his forehead. The brothers were somber when they left Kitty Hawk on August 22. Despite Chanute’s praise, they considered their experiments a failure and doubted if they would continue. Wilbur told Orville on the train ride back to Dayton, "Not within a thousand years would man ever fly."

1901 - 1902 In quest for answers

Back in Dayton, Octave Chanute invited Wilbur to address the ‘Western Society of Engineers’. This was a great honour and first ever recognition of the Wright Brothers’ experiments. However, the shy Wilbur politely refused and it took a lot of persistence from Katherine to get Wilbur on stage. His speech, simply titled "Some Aeronautical Experiments" was well received and a copy was published in the prestigious ‘Journal of the Western Society of Engineers’. It was the first public account of their experiments. During the next few months, the brothers set out to solve the lift and control problem of their gliders. They started testing by mounting a wheel horizontally to a bicycle and furiously pedaling around their neighborhood. The strange looking bicycle was too crude to make accurate measurements and the Wrights’ then made a wind tunnel from an old grinder and scraps of wood; and made delicate balances from hacksaw blades and bits of wire. They tested a variety of wing shapes in the tunnel and by mid-December 1901, they gathered the knowledge that enabled them to build an aircraft with enough lift to support its weight in the air. The other big puzzle to solve was the control problem.

1902 – Third time lucky

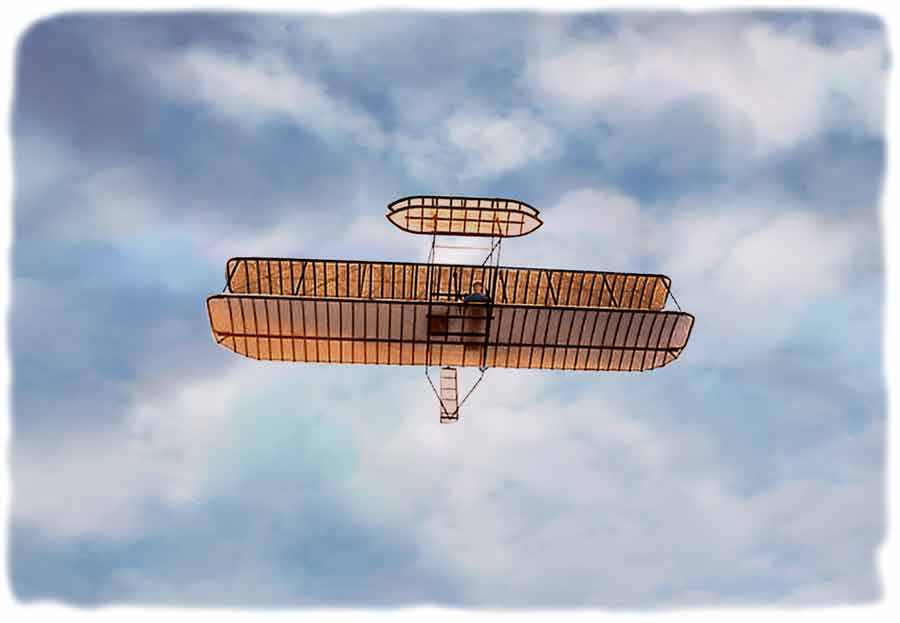

It was their third successive year in Kitty Hawk and also the year when they made substantial progress. Unlike the previous models, the new glider consisted of a tail and a much improved wing design. The amount of lift produced by this new wing design was very close to what the brothers had predicted. Within a few weeks, they were making glides of over 500 feet. For the first time, Orville began to fly. To allow better control while turning, the tail was transformed into a movable rudder with its own separate control. This was the last piece of the control puzzle. The movable rudder made the 1902 Wright glider the first aircraft capable of being precisely balanced in flight

So important was this breakthrough that every aircraft flying today, still uses the same fundamental controls of the wings and tail. The Wright brothers’ successful flights were witnessed by Chanute and other aerial investigators such as Augustus Herring. Wilbur made a glide covering 622 feet; Orville’s best was 615 feet. Having licked the control problem, they honed their flying skills as they planned their next step - a powered aircraft.

1903 – The year of conquest

While the Wrights’ began working on their engine powered glider in Dayton, Octave Chanute took a business-cum-pleasure trip to Europe that would have a profound impact on the Wrights in later years. On April 2, 1903, while passing through France, Chanute addressed the ‘Aero-Club de France’, a group of aeronautical engineers, experimenters and enthusiasts and described the gliding experiments of the Wright Brothers, particularly their wonderfully successful 1902 season. The French engineers were stunned to hear about the steady progress of the two American bicycle makers. They could not allow the great invention of flying machines to be accomplished on foreign soils and decided to set out in hot pursuit of the Wright Brothers.

Across the Atlantic in Washington, DC, Dr. Samuel Langley who was working on his great Aerodrome models since 1896, made two disastrous attempts in October of 1903, when his Aerodrome failed to fly and fell into the Potomac River. Langley was ripped to shreds in the newspapers.

The D-Day Arrives

Meanwhile, the Wrights’ arrived in Kitty Hawks on September 1903 to test their first engine powered glider called the ‘Wright Flyer 1’. After nearly four months of labour on the new engine and propeller system, the flyer seemed ready to take to the air by December 12, 1903. But the wind was too light to fly and they decided to skip their attempt. The next day was a Sunday and a perfect day to fly, but the brothers had promised their father they would not break the Sabbath by flying on Sunday. The following Monday, the brothers decided to take a chance and test the flyer, inspite of the light wind wind. Orville and Wilbur tossed a coin to see who would be the first to fly, and Wilbur won.

Orville started the engine and Wilbur began to maneuver the plane But the flyer stalled and hit the ground within a few feet and the wings snapped. Another failed attempt, but the one solace for the brothers was that the machine had left the ground under its own steam and could fly once it had been repaired. Success was just around the corner.

The day of reckoning finally came calling on 17th December, 1903. It was winter, the winds had become fiercer at Kitty Hawks and it was nearly Christmas. The Wrights’ were anxious to get back home but with no successful flight, going back would mean another year of waiting. The brothers had been ever so cautious and calculative during their entire research but this time, these prudent, sober, intelligent men literally threw their considerable caution to the wind.

1904 – The year of tribulations

Following the triumph of 1903, came the tribulations of 1904. The flying experiments were burning a hole in the pockets of the Wright Brothers’ and they decided to monetize their flying expeditions in some manner. For that, they required a patent first. They hired a patent attorney Henry A. Toulmin who advised them to continue their work but under secrecy, until the patent was granted. To bring down their expenses, the brothers decided to flight test their gliders at Huffman Prairie, a cow pasture eight miles northeast of Dayton.

They even invited journalists to witness their new glider, the Flyer 2 in action on 23rd May, 1904 on the condition that no photographs were taken. The tests were a no show and the Flyer 2 could manage only a few hops, much to the disappointment of the gathered crowd, including their father Milton Wright. The problem was the soft breeze at Huffman Prairie which could not provide the flyer enough lift to make a successful launch. With nothing exciting to report, the journalists left and lost interest in the Wrights’ work for the next one and a half years. This was the only positive point that the brothers could draw from that year as the failure of the Flyer 2 helped them get rid of the attention from the media and their competitors.

1905 – World’s First practical airplane is born

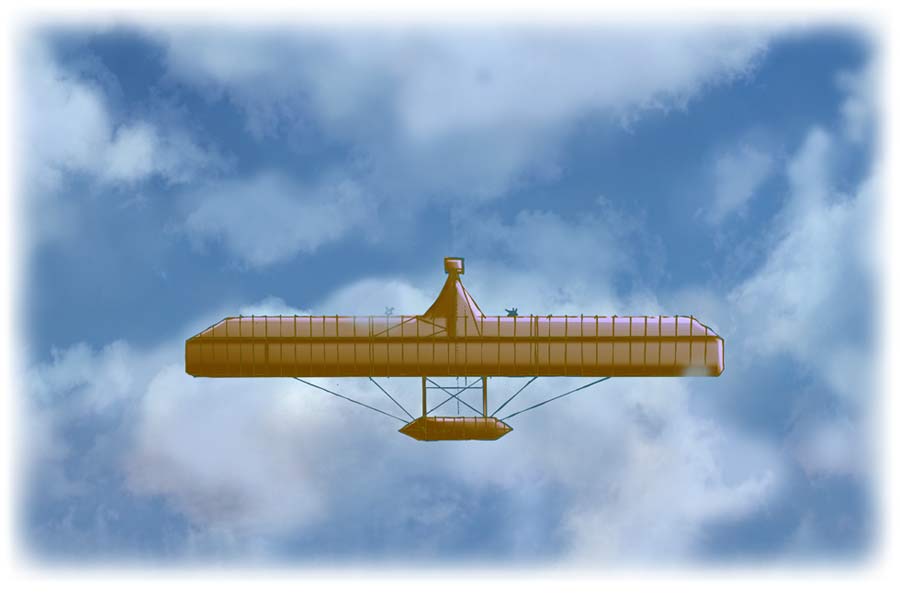

From May 1905, the brothers began work on ‘The Wright Flyer 3’ which had a larger rudder and an elevator. The elevator was placed 12 feet away from the wings for better control. The 1905 Wright Flyer III was the marvelous fruit of careful, painstaking engineering. Built up in tiny increments, beginning with the Wrights’ kite experiments of 1899, it was the first flying machine capable of taking off and flying through the air under its own power; rising, descending and turning in any direction under the control of a pilot; and landing in any suitable location without crashing. In short, the Flyer 3 was the world's first practical airplane. On September 26, Wilbur flew it over for 18 minutes, running theas tank dry for the first time. Orville later broke the half-hour mark on October 3.

With these successful flights, years of hard work and perseverance had finally paid off. The flyer was undoubtedly a result of centuries of research and studies in the various disciplines of Physics and Aerodynamics. Right from ‘Newton’s law of Gravity’ to ‘Leonardo Da Vinci’s’ helicopter sketches to the ‘Chanute-Herring Biplane glider’ to ‘Lilienthal’s’ daring flights in Germany, all had played a vital part in Wright Brothers work but where others had failed, the Wright Brothers’ fortitude and genius had prevailed. And their virtuoso did not remain concealed for too long.

Word had spread that something special was happening over at Huffman Prairie. Scores of people would gather to witness the Flyer 3 in the air. The newspapers caught on the frenzy and stories appeared in the ‘Dayton Journal’, ‘the Dayton Daily News’ and the ‘Cincinnati Post.’ Knowing that premature exposure could place their patent rights and financial future in jeopardy, the Wrights’ decided to halt their test flights until they had secured a patent and a buyer for their aircraft. The triumphant 1905 flights would be the last they would make for nearly three years.

The First Patent

If inventing a flying machine was a laborious task, the Wrights’ realized that making a business out of it was an even tougher proposition. The Wright Brothers’ were desperately seeking out for funds in the wake of their dwindling bicycle business. But they made no headway either home or abroad. They were completely snubbed by the officials of the US Army and their negotiation with the British War Office and the French and German government did not yield anything productive either. Nobody was interested in buying the flying machines from bicycle makers. The anti-Wright stance taken by the European media, especially the French press, made matters worse. Headlines such as ‘Flier or Liars’ further slowed their progress in setting up an aviation business.

Relief finally came on 23rd May, 1906when the United States granted ‘Patent Number 821,393to O. and W. Wright of Dayton, Ohio for a Flying Machine.’ This would later come to be considered as the ‘grandfather patent’ of the airplanes in the years to come.

Breakthrough at last

Then in 1907 with the help of Charles Flint, a highly successful New York dealmaker, Wilbur and Orville travelled to Europe to speed things up with the French and German governments. Although the deal did not go through, their visit made a very important impact. While in France, they met and became friends with Lieutenant Frank Lahm, who had recently been asked to join the new aeronautical section of the United States Army Signal Corps. Lahm wrote a letter to his commander, Brigadier General James Allen stating that it was "… Unfortunate that this American invention, which unquestionably has military value, should not first be acquired by the United States Army." The letter had the desired effect and it geared the US Army to take the invention more seriously.

The brothers finally got their first contract from the US Army in December 1907 to build a two seater aircraft that could travel for 125 miles at the speed of 40 miles/hour and be able to land without damage. This meant modifying their Flyer lll design to carry a co-passenger, so the Wrights’ travelled to Kitty Hawk after a gap of 2 years to work on a modified version of the Flyer. They called it ‘Model A’. In January 1908, they got another order from a French company. Their contracts required public demonstration of their flying machine and so the brothers decided to split their efforts. Wilbur sailed for Europe while Orville would fly near Washington, DC.

The Wrights had faced skepticism in France but when Wilbur took to the air in France, he turned into a hero overnight. The French public was thrilled by Wilbur's feats and flocked to the field by the thousands. Former skeptics issued apologies and effusive praise. Orville followed his brother's success by demonstrating another nearly identical flyer to the United States Army at Fort Myer, Virginia, starting on September 3, 1908. On September 9, he made the first hour-long flight, lasting 62 minutes and 15 seconds.

But on September 17, 1908, tragedy struck. Army lieutenant Thomas Selfridge was riding alongside Orville as an official observer when the propeller split at about 100 feet from the ground and the flyer plunged to the ground. Orville escaped with injuries but Thomas Selfridge perished in the accident; this was the first time that the Wrights’ flyer had claimed a life in flight. Orville was admitted to a hospital in Washington,DC and Katherine, who had been teaching in Dayton, came to Washington to look after him. Following the disastrous crash and Orville’s prolonged recovery, the US Army contract looked to be lost. Little Kate had always put family first and realizing that her brothers’ effort could all go in vain if the contract was cancelled, she decided to give-up her teaching career and got herself familiar with the science of aviation. She studied the ins and outs of the contract and her brothers’ flying machines. Her astute skills as a negotiator finally helped the Wright Company negotiate a one year extension of the Army contract while her brother recovered from his injuries.

From Zeros to Heroes

The accident spurned Wilbur, who was in France, to further up his effort and prove the world they were not bluffers. Each day he set new records, with the best being 2 hours, 18 minutes, and 33 seconds on December 31, 1908. In January 1909, Orville and Katherine joined him in France, and for a time they were the three most famous people in the world, sought after by royalty, the rich, reporters and the public. The kings of England, Spain and Italy came to see Wilbur fly. Katherine became the social interface of the reclusive Wright brothers and provided the charm the Wrights needed to make their aviation enterprise work. She was regarded as the ‘Third Wright Brother’ by the European press and awarded the ‘Legion of Honour’ from the French government along with Wilbur and Orville.

When the three Wrights returned to US, the reception was even more magnificent with high profile meetings with the then President of US, William Taft. Back home in Dayton, they became heroes and awards and recognition poured in from the local people and government. They completed their army contract by flying at a speed of over 40 miles/hour and sold their aircraft for $30000 with a $5000 speed bonus. President WilliamTaft awarded the very first Langley Gold Medal or the Samuel P. Langley Medal for Aerodromics to the Wright brothers in 1910, for their outstanding contributions in the field of aeronautics.

Wilbur commemorated their successful year with a flight around the Statue of Liberty which lasted 33 minutes and was watched by 1 million New Yorkers The fame of the Wright Brothers was now well established.

The Patent War

While Wilbur and Orville were away in Europe to show the world that they could fly, back home, another group of aviators had gathered to form ‘AEA’or ‘Aerial Experiment Association.’ It was headed by the then Secretary of the Smithsonian Institute, Graham Bell, the inventor of the telephone. The group which had the US Army’s full support included Glen Curtiss, a successful bike manufacturer, who would later lock horns with Wright Brothers on a long-running patent dispute. THE AEA developed their own aircrafts, drawing heavily from the works of the Wright Brothers. In fact, the AEA approached the brothers for advice to which the brothers responded graciously. Out of respect for Graham Bell, the brothers answered questions about engineering and materials and directed the members of the AEA to published papers and patents for more in-depth information.

After a couple of unsuccessful models, the group finally tasted success in the summer of 1908 with their third model called the ‘June Bug’ which was the first successful aircraft of that time. However, its biplane frame and the control system all resembled the Wrights’ flyer. Encouraged by this, Glen Curtiss decided to launch an aviation company to manufacture and sell aircrafts. But he knew that this would lead to patent-infringement and to circumvent any dispute, he joined hands with Augustus Herring who claimed to hold patents that pre-dated the Wrights.

On June 26, 1909, Glenn Curtiss of the newly incorporated Herring-Curtiss Company sold an airplane to the Aeronautical Society of New York — the first private airplane sold in the United States. He travelled to Europe to show his machine called the Golden Flyer and participated in exhibition flights and trained others. On July 17, he flew the Golden Flyer for 25 miles and captured the ‘Scientific American Trophy’ – a coveted trophy given to a person who could fly the longest distance. This stretched the Wright's patience to the breaking point. Wilbur filed a patent-infringement suit against Curtiss on August 16 and another on August 19, in order to prevent the Aeronautical Society from flying the Golden Flyer. It was the first shot in what would be known as the ‘Patent Wars.’

The Wright Flying Company

In the fall of 1909, with Wilbur as President and Orville as Vice-President, the brothers officially launched their aviation business by forming the Wright Company. They sold their patents to the company for $100,000 and also received one-third of the shares in a million dollar stock issue and a 10 percent royalty on every airplane sold. The company set up a factory in Dayton and a flying school at Huffman Prairie. The headquarters was in New York City.

As their fame grew, orders for aircraft poured in. The Wrights set up airplane factories and flight schools on both sides of the Atlantic. Unfortunately, once they had demonstrated their aircraft in public, it was easy for others to copy them. The Wrights were dragged into time-consuming and energy-draining patent fights in Europe and America. They got temporary relief from the Curtiss dispute in 1910 when the court ordered an injunction against the Herring-Curtiss Company, thereby preventing them from selling aircrafts.

Outside the courtroom, the world seemed no friendlier to Wilbur and Orville. The aircraft business was uncertain and dangerous. Most of the money to be made was in exhibition flying, where the audiences wanted to see death-defying feats or airmanship. The Wrights sent out teams of pilots who had to fly increasingly higher, faster and more recklessly to satisfy the crowds. Inevitably, the pilots began to die in accidents and the stress began to tell on the Wrights. Additionally, their legal troubles distracted them from what they were best at - invention and innovation. By 1911, Wright aircraft were no longer the best flying machines. Their model C flyers that were sold to the US Army began to crash with as many as 11 deaths and the military announced the Wrights’ flyer to be unsafe for flying. This came as a big jolt for the Wright Company. Wilbur claimed the accidents were due to the result of pilot errors but their reputation had been dented.

1912 – Tragedy Strikes

The Wright Brothers had been a perfect team all these years. They had been together for so long, understanding each other, sometimes arguing, nonetheless sharing the glory together. But in 1912, the team was cut in half. On May 30, at the age of 45, Wilbur Wright, worn out from legal and business problems, contracted typhoid and died.

From the time Wilbur and Orville were little boys, they had lived together, played together, worked together and even, thought together. They shared all their toys as well as their aspirations, their triumphs as well as the tribulations right from their boyhood days. But with Wilbur’s death, their perfect partnership that had lasted for 40 years came to an abrupt end. For the first time in his life, Orville was on his own. He reluctantly took over the company and Katherine was inducted as an officer to assist Orville in day-to-day business. Once again, the love between the Wright siblings helped Orville bear the tragic loss.

Meanwhile, their arch enemy, Glenn Curtiss came up with another ingenious plan to circumvent the Wrights’ patent. He returned with a new aircraft model which was based on Langley's unsuccessful Aerodrome design and went on to prove that the Aerodrome could have flown before The Wright Flyer. The farce did not work however as Curtiss had made too many modifications to get Langley's aircraft in the air. The United States Court of Appeals ruled in favor of the Wrights on 13th January, 1914 and upheld the Wright Brothers 1906 patent, declaring it to be the ‘grandfather’ patent of the airplane. Although the case resolved the bitter Wright/Curtiss dispute, it left an enduring resentment between the Wrights and the Smithsonian.

Orville, his heart no longer in the airplane business, sold the Wright Company in 1916 for $250,000 and went back to what he did best - inventing. Kate continued to be the mistress of the Wright home. Their father, Bishop Milton Wright, died in 1917 and subsequently, Kate and Orville moved into a mansion they called Hawthorne Hill, just south of Dayton.

Back to Inventions

With patent fights and business troubles behind him, Orville Wright built a small laboratory in his old Dayton neighborhood. Here, he contracted out as a consultant on a wide variety of engineering problems. He also took up a number of projects that caught his imagination. He did much aeronautical work, helping to develop a racing airplane, guided missile and ‘split flaps’ to help slow an aircraft in a dive. He also worked on aerodynamic automobile designs, toy designs and even a cipher machine for encoding communications.

His fame as the co-inventor of the airplane endured and he put it to good use. He was on the original board of the ‘National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics’ (NACA) and served longer than any board member.

NACA later became the ‘National Air and Space Administration’ (NASA.) He helped oversee the Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics, an effort that helped America recapture the technological lead in aviation during the late 1920s.

Orville and his brother Wilbur had toiled for years to get the recognition for their effort even after their magnificent invention. Orville was well aware of the struggles and so he worked tirelessly to help unknown inventors bring their ideas to market.

The childhood vow is broken

On the personal front, Orville continued to stay with his sister Katherine who was now 55 and still single. Then in 1926, Kate decided to tie the knot with Henry Haskell, a former classmate, which enraged Orville. Kate was his best friend, his confidant and he depended on her more after Wilbur’s death. He refused to attend the wedding ceremony, and Henry and Kate moved to Kansas City without him saying a word to them. Katherine tried many a times to reconcile with her brother, but Orville ignored her. Then, just two years after she married, she contracted pneumonia. Even then Orville would not write or call. When it became obvious that she was going to die, Orville's elder brother Lorin, finally convinced Orville to visit her. Orville travelled to Kansas City in time to be with Katherine when she died on March 3, 1929. Orville was once again all alone.

The war with Smithsonian

Though Orville made peace with Kate before her death, his long-running battle with the Smithsonian Institute (over who were the rightful pioneers of practical flying machines) saw no resolution in sight. After the First World War, the Smithsonian exaggerated Langley's contributions to aeronautics while seeming to belittle the Wrights. Friends of Orville set the record straight, but the Smithsonian kept on. In retaliation, Orville sent the 1903 Wright Flyer, the airplane in which he and Wilbur had made the first powered flight at Kitty Hawk, to the Kensington Science Museum of London in England. In the 1930s, Charles Lindbergh, the first aviator to fly from New York to Paris nonstop, attempted to mediate the feud, but to no avail. It was not until 1942 that Orville Wright's friend and biographer, Fred Kelly, convinced the Smithsonian to back down and publish the truth. That done, Orville sent word to England that the flyer was to be brought home to America. Its return was delayed by the Second World War, but it was finally returned in 1948.

The Last Project

Orville's last big project was, fittingly, an aircraft. He helped to rebuild the 1905 Flyer 3, the first practical airplane, which he and Wilbur had perfected at Huffman Prairie. This was put on display in the Deeds Carillon Park in Dayton, Ohio in 1950, but Orville did not live to see the ceremony. He suffered a heart attack in 1948 and died a few days later. Having lived from the horse-and-buggy age to the dawn of supersonic flight, Orville’s remarkable journey had come to an end. But his name along with Wilbur’s continues to fly high in the world of aviation even today. Both brothers are buried in the family plot at Woodland Cemetery, Dayton, Ohio.

A Glorious Life

The Wright Brothers had embarked on one of the most perplexing and dangerous research projects ever attempted, so dangerous that they escaped death by the skin of their teeth more than once. Together, they built sevenflying machines in their quest for a practical aircraft, each a step closer to that elusive flying machine. When they guessed wrong, they paid a heavy price – they crashed. But with each crash, the Wrights’ learnt and rectified and this eventually led them to build a flying machine that actually worked. In less than a decade, they taught themselves to fly and became pioneers of the flying machines.

The Wright Brothers proved to be inept businessmen, but no one can deny the fact that their brilliant inventions changed the course of the aviation industry. Although there is much debate on who actually flew first, one fact that is certain and widely accepted is, that the Wrights were the first to make a sustained and controlled powered flight. The simple bicycle makers from Dayton, Ohio are the undisputed inventors of the first practical airplane. They gave their entire lives to flying and in fact never married. As Wilbur would say, “Did not have time for both a wife and an airplane.”

Before their ingenious invention, the world was rigid two-dimensional with artificial boundaries stretching from town to town and nation to nation. But ever since The Wright Flyer 3 took to the air from Kitty Hawk in 1905, these artificial boundaries disappeared. Distances shrank, the world seemed smaller yet grander and people got interconnected seamlessly. This three-dimensional vision revealed a universe of promises and possibilities. The world economy, our awareness of our environment and space exploration is, to some degree, the results of the inventive thinking and hard work of Wilbur and Orville Wright.

The Wright Brothers’ tale of invention remains a symbol of the never-say-die attitude of mankind and continues to inspire millions of pioneers worldwide.

Next Biography