Look around you, what do you see? I see growth, upward and onward. While savoring the fruits of the 21st century, we more or less have disremembered or rather have been ignorant, to acknowledge the sacrifices previous generations made for us...for you! The following account will take you two centuries back to illustrate how an Entrepreneur built a nation. As a reader, you will be enlightened today by the life experience of one the richest Iron and Steel Tycoon the world has ever seen…. Andrew Carnegie. The steel he made became the backbone of modern America. This 19th century industrial icon spent one good half of his life accumulating wealth and the other half distributing entirely through philanthropy. His greed and never say die spirit made him a millionaire and his philanthropy earned him respect.

Andrew Carnegie’s story from rags to riches is worth reading, if you seek to unshackle yourself from working class Tellurian life. I am confident, that after reading the life history of Andrew Carnegie, you will no longer feel infuriated, or blame your personal failure on your upbringing, government system or your god!

Pessimists have remarked that throughout history, entrepreneurs have earned their fortunes by bloodshed. I could not agree more, that the entrepreneurs have made it big by shedding blood…their own blood! As a writer, I feel it is my responsibility to enlighten you on this subject and in this process if I evoke and inspire you to be entrepreneurs then don’t forget to send me a thank you note.

“Perhaps the most tragic thing about mankind is that we are all dreaming about some magical garden over the horizon, instead of enjoying the roses that are right outside today.”

Andrew Carnegie was born in a shabby attic of a single room cottage in Dunfermline, Scotland on 25 November 1835. Father William Carnegie was a humble linen weaver and sole breadwinner of the family. Mother Margaret a woman of poise was the anchor of the family. It was an era when hand woven linen Industry was at its peak. Highly skilled weavers like William Carnegie, were considered as expert artisans. Will’s handmade Linen was in demand and he owned five handlooms in his one storey cottage, where Andrew would sit for hours admiring rhythmic sounds of shuttles and foot paddles. Andrew aged 10, was mesmerized by the rampant industrialization in the country. His innocent eyes, failed to see, that steam powered looms imperiled the existence of handloom weavers. William Carnegie was crushed under the spinning wheel of progress.

There were days when the family slept without a meal. Andrew however beamed like sunshine, his optimistic nature and the quality to laugh even in troubled times, helped him survive the gruesome hapless days. Andrew Carnegie over the years cultivated this natural gift and made “ducks appear as swans”. The poor but honest parents provided young Andrew the virtues of humility and wisdom, and ingrained him with politeness and optimism. “Thine own reproach alone do fear” was a philosophy he religiously followed throughout his illustrious life. Andrew grew up in the environment, where antimonarchy and aristocratic government prevailed. Margaret, who was emotionally stronger than her husband, ensured her sons were bestowed with good morals and ethics.

“If you want to be happy, set a goal that commands your thoughts, liberates your energy, and inspires your hopes.”

The Carnegies moved from Moodie Street to Rieds Park, due to their impoverishment. Though deprived of essentials, Andy was showered with knowledge of politics and economics. The art of public speaking drew his attention. Andrew Carnegie’s father and uncle participated actively in debates and gave eloquent speeches on political subjects. It helped Andrew to overcome his shyness and be vocal in his area of interest.

Andrews’s real lesson in life began, when his father, under the crushing pressure of Industrialization had to sell off his five handlooms one by one. When William, went to flog the last web, Margaret anxiously waited for him to know if he would bring home new work or the wretchedness of unemployment. Andrew’s heart burnt when he saw his father begging for work. To repair the finances and maintain clean collars of the family, Margaret took up shoe mending jobs and opened a grocery store in her house. She was determined to reinstate the lost pride, comfort and respectability of her family. Witnessing privation from a close range, Andrew Carnegie’s heart wept seeing his mother mending shoes of neighbors. Still the sunshine boy, Andy, as optimistic as ever endeavored to support his family through thick and thin.

At the Age of 12, he understood poverty and hunger, up and close. His parents could no longer afford his schooling. The pertinacious requests from Headmaster Robert Martin, aided Andy continue further. Andrew often served his parents by doing household chores, like fetching water from the well, buying groceries that always made him late for school. Andrew earned a nickname “Martins Pet” as his schoolmaster, often pardoned his innocent mistakes. After returning from school, he helped his mother at the grocery store.

A mentor teaches valuable lessons which no amount of books can provide. Andrew Carnegie’s very first mentor was his uncle-George Lauder, husband of Margaret’s younger sister.

Andrew Carnegie’s maternal Uncle George Lauder owned a shop at High Street, home to aristocrat shopkeepers and businessmen. Andy highly cherished spending time with his cousin George Jr. as they learned a great deal of history, of Scotland and Britain from Uncle Lauder, in an interactional manner. So proud was Andrew, of his rich Scottish heritage that he took pains, reciting old folklore and poems of bravery and patriotism! His mentor ensured that the boys learned and understood the values and wisdom, which came along with the literature. Lauder urged the young boys to give speeches and perform skits, which boosted their self-confidence and sharpened their public speaking skills.

To encourage the blighters in memorizing phrases, quotes and Psalms, the uncle rewarded them with a penny. Andrew made it a habit of reciting quotes and psalms while walking towards school. The Carnegie’s were never orthodox Christians; as a matter of fact William had objections to catechism and Calvinism. William believed in God, but he never forced his wife and children to visit churches or recite Psalms.

“There is little success where there is little laughter”

You do not have to be technically perceptive or mechanically brilliant to run a business or industry. An entrepreneur needs to know how to handle only one complicated machine … man!

Wonderful parents that the Carnegies were, they often gifted their children rabbits and pigeons as pets. Thrilled by his own private menagerie, Andrew soon realized that feeding these animals was becoming troublesome. The businessman within him rose to this opportunity and created a pact with his friends. He offered to name his pets, in the name of the kids who brought fodder for the animals every day. The marketing strategy was spot on; he never had to part away from his pets while other kids were satisfied that the animals were named after them. Here he learned life’s most valuable lesson:

“Teamwork is the ability to work together toward a common vision. The ability to direct individual accomplishments toward organizational objectives. It is the fuel that allows common people to attain uncommon results.”

Despite his successful venture, Andrew was always torn between the ideologies of his father and mother. William believed in democracy and the rights of people. Margaret on the other hand was materialistic and was determined to better her status. She dreamed of living and owning a shop at high street, rubbing shoulders with the rich and the famous.

You struggle hard; go down on your knees and perish and the world will soon forget you!

No matter how hard Margaret tried, the family could not relocate from Queer Street. The business subsequently suffered, as the location was unfavorable from the customer’s point of view. As a consequence a decision was arrived at; they were migrating to the land of promise… America! As a child, Andrew was fascinated looking at the map of America where his maternal aunt and uncle had moved to a little earlier. The grandeur of republican system of governance and the promised liberty in America attracted many Europeans to the land of promise.

Margaret arranged for an auction of her cottage and furniture. Sadly, the proceeds of the sale were disappointing. They were still short of 20 pounds for the entry and passage to America. Margaret took a loan from her neighbor, Mrs. Henderson. On 17 May 1848, William now aged 43 and Margaret 33 with their sons Andrew and Tom left Dunfermline dejected. It was a tearful departure, as Andy looked out of the window of his carriage to see the Abbey Church, slowly disappear in the distance. For the next 14 years, Andrew constantly asked himself if he would ever see his town again.

“Pittsburgh entered the core of my heart when I was a boy and cannot be torn out.”

United States of America then was still a land of promise. It welcomed you with open arms, if you believed in the spirit of liberty and hard work. In 1848, more than 190,000 left Britain for America in the hope of a bright future.

After an agonizing voyage that lasted 7 weeks, the Carnegies arrived in New York with a heavy heart. The family was bewildered with the hustle and bustle of the city. They moved into Mr. & Mrs. Sloane’s home for a couple of days and continued their Journey to Cleveland, by boat which lasted 3 weeks, as there was no railroad. The onward journey was by wagons, which ended in Pittsburgh, more specifically Allegheny City. Fortunately, the family got a shelter in a friend’s vacant apartment, in Slab Town where filth, stench, poverty and despair greeted them. Shortly after, William set up his hand weaving looms, and started making tablecloths and sold them door-to-door, for a meager profit. It was Margaret, the woman of iron who came to the rescue once again, by mending the shoes of the neighbors and earned survival money.

“When fate hands us a lemon, let's try to make lemonade.”

Andrew, while leaving the shores of Scotland, pledged silently to heal the wounds of his father’s defeat. He was unaware that his acid test was lurking round the corner.

Margaret was always very protective as she was proud; the idea of her son selling knickknacks on the wharves enraged her. She did not want Andrew to hang out with the shady seamen who were loose of character. With the passage of time, his father realized he no longer would be able to run his business, and hence joined a cotton mill factory. A little later, Andrew joined the same factory, working as Bobbin-boy for $1 and 22 cents a week. He woke up early in the morning before sunrise and worked until late night.

Despite the sheer drudgery, the optimistic Andrew was overjoyed that he was making a small contribution to the family. Andrew Carnegie confessed years later when he had amassed huge wealth, that he did not feel as satisfied, as he did when he had earned his first salary.

Later, Andrew worked in another factory, where he operated a small steam engine and fired up the boilers, 12 hours a day for meager wage of $2 per week. The heat and the working conditions often gave him nightmares, as the risk of bursting boilers and fire were rampant, real dangers. However, like a true Scotsman, Andrew was determined and never gave up. His minimal education, gave him an opportunity to work in the office, as a clerk, where he wrote letters and prepared bills for his boss. Still short of bookkeeping skills, Andrew ascribed to a night school in Pittsburgh and learned double entry bookkeeping and accountancy.

There will be times, when your patience will dry up and frustration will crawl in, but the one who holds his ground emerges victorious.

In 1850 Andrew now 15, secured a position of a messenger boy in a Telegraph Office. From a steam boiler heat to the comfort of an office filled with pencils, books and newspaper was a welcome change and seemed a paradise. Privy to information of companies’ reputation and their credit ratings, Andrew, learned about commerce, politics and business communication. On his message delivery trips, Andrew memorized every street in downtown Pittsburgh. He would never forget the faces and the names of the businessmen he met every day. Andrew made it a habit of greeting people of stature in the street by their name, which placed him in their good books. He visited bars and saloons where rich businessman and influential politicians confabulated.

Those days in the office saw Andrew also wiping floors without griping, on alternate days with his friends David McCargo and Robert Piteairn. Together they delivered messages on Eastern Telegraph Line in Pittsburgh. The young boys, loved to deliver messages to Bakery owners and shop vendors, who would sometimes treat them with hot cakes and apples for prompt deliveries.

“No man becomes rich unless he enriches others.”

Working late till midnight, left Andrew no time for self-improvement. He was still alien to the vast knowledge the world had to offer. Thanks to Colonel James Anderson, an open library was established, where working boys could borrow books on Saturday and return it for a new one on the next. Andrew’s close friend, Tom Miller made a special arrangement for him to access books on every weekend. Andy read those books mirthfully snatching time between his working hours. He read a great deal of American history, English essays and literature. Knowledge was essential for his growth and Andrew Carnegie was not an ignorant fool. Apart from books, Andy loved the performing arts and theater, which stimulated his love for Shakespeare. As the messenger boys could not afford theater tickets, they delivered Mr. Foster’s [The Theater Owner] messages free, and in return had free access to the shows. Some of the boys even deliberately withheld his letters only to get a free admission to the vaudeville.

The rising green curtain at the theater fascinated 15 year-old Andrew Carnegie. The grandeur of the stage and the floodlights enchanted him. Apart from the theater, Andrew rejuvenated himself by skating on the frozen lake or went boating with friends and relatives during summers.

“You cannot push anyone up the ladder unless he is willing to climb himself.”

Within the first year, Andrew Carnegie was handling managerial operations in the absence of his superiors. Now earning $11 and 50 cents, Andy maintained his habit of thrift. His penurious quality often irked his friends, who lavishly spent their monthly wages. Andrew was well aware of his financial obligations and contributed to pay off the loan of 20 pounds, which the family had initially taken while departing from Scotland. The day the loan was repaid, the Carnegies celebrated their triumph; William was now free from the burden of debts. Under tutelage of Colonel John P. Glass (His boss), Andrew learnt the intricate nuances of the Telegraph business. He worked hard to prove his worth to his superiors. At the end of the month when Andrew patiently awaited his salary, he was surprised to find $13.50, a straight $2 raise. Imagine the exuberance of this boy, who got his very first promotion. Back at home, Andrew gave $11.50 to his mother without telling her about the raise. At night, ogling at the 2-dollar bill, Andrew dreamt of the day when he would become a millionaire and the luxuries he would buy. Next morning, Andrew placed his $2 on the breakfast table. The Carnegie’s were so overwhelmed that William beamed with joy and Margaret wept proudly.

The promotion gave Andrew Carnegie the motivation he needed; he realized he was worth getting promoted. Soon he started learning the telegraph with great zeal. One day an urgent “Death message” had arrived, but due to the absence of the telegraph operator, Andy decoded the message accurately and delivered it quickly. By the age of 17, Andrew had advanced as a full-time telegraph operator with a $25 a month salary.

“People who are unable to motivate themselves must be content with mediocrity, no matter how impressive their other talents.”

Every illustrious personality has one thing in common…. A Purpose! An aimless wanderer is destined to rendezvous with failure. One day Andrew saw his father on a boat deck, returning from Ohio and Cincinnati, selling tablecloth. To save money, his father travelled on a boat as a deck passenger all night, instead of buying a ticket in a comfortable coach. Andrew felt as if his heart was pierced, when he saw his father’s sacrifice. He was ashamed that he had forgotten the silent pledge he took to heal the wounds of his father’s failure. He announced …

“Well father, it will be not long before mother and you shall ride in your carriage”

With tears in eyes William replied…

“Andra, I am proud of you”

It was Andrew Carnegie’s trigger point. He vowed that his father, the broken man and the victim of the industrial revolution would one day bask in the glory of wealth.

“No man will make a great leader who wants to do it all himself or to get all the credit for doing it”

Thomas A. Scott, superintendent of the Pennsylvania Railroad, frequented Pittsburg Telegraph office where Andrew was stationed as an operator. In order to urgently communicate with his superiors, Scott would sometimes turn up at the office late night when mostly Andrew would be working. Scott admired Andrew’s efficiency and asked him to join his company as a clerk and telegraph operator. 18-year-old Andrew agreed and started earning $35 a month; a staggering achievement. His association with Scott gave him access to many influential as well as coarse people. The railroad industry was relatively new and attracted hard core laborers who lacked manners and used all sorts of foul language.

Under his mentorship, Scott watched his protégé progress rapidly. Andrew Carnegie now handled more responsibilities than ever before. One day, to test his abilities Scott sent Andrew to Altoona city, to collect monthly payrolls and checks for Pittsburgh executives and workers. Andrew was perked up on the prospect of handling responsibility and a trip by train for the first time. Once in Altoona, Andrew met General Superintendent of Pennsylvania Railroad, Mr. Lombaert, who instantaneously invited Andrew to his house for dinner. Andrew was proud to be considered as ‘Scotts Andy´ the right hand man of the Pittsburgh Superintendent. It would be wrong to assume, that life of Andrew Carnegie was now smooth. One incident almost ended his career, as he lost the wages while riding in the engine. Luckily Andrew realized he was missing a package before reaching Pittsburgh. He asked his engineers to reverse the locomotive and soon spotted the package lying on the banks of a river untouched or damped.

“Do your duty and a little more and the future will take care of itself.”

A young man should undertake work beyond his sphere of duty, as it attracts the attention of his superiors. One day, Andy arrived in the office and was informed, that one of the company’s trains had met with an accident. The engine was derailed and it disrupted services on that route. It was one of the worst train wrecks in the history of the Pennsylvania Railroad. In absence of Thomas Scott, a decision had to be made, without wasting more time; Andrew Carnegie gave orders to his workers under the signature of Thomas Scott. The situation was soon under control and the trains resumed their journey. Hours later when Thomas arrived, Andy was petrified; he came forward and explained the whole situation to him. Scott was flabbergasted to hear of his protégé’s gamble, and walked away without a word. Next day Andrew learned from a fellow worker that Thomas Scott could not stop praising his protégé for his proactive thinking and decision-making.

When another train wreck hampered the transportation of the railroad, Andrew Carnegie assuming authority took charge. He ordered his men, to burn down the wrecked wagon lying on the tracks. Andrew Carnegie’s ideas though unconventional were highly effective. The trick worked and the railway line was restored. Such methods were never applied before, but it now became the company’s standard procedure in order to move things faster.

“Immense power is acquired by assuring yourself in your secret reveries that you were born to control affairs”

The company was laying telegraph lines along the railway line and Andrew had a bigger role to play in the entire venture. Scott and Andrew together built bigger coaches, freight cars and longer trains to carry bigger loads and more passengers. This helped bring down the cost drastically. With the help of Andrew, Pennsylvania Railroad provided 24 hours and 7 days a week telegraph and train service. Soon the business flourished and Andrew Carnegie was indispensable.

20-year-old Andrew Carnegie’s reputation preceded wherever he went. John Edgar Thomson the president of Pennsylvania Railroad thought very highly of Andrew. Scott would give charge to Andrew in his absence and Andrew rose to the occasion and proved his worth. Unfortunately, in order to prove himself to his boss, he often took harsh measures. One day, when a small mishap took place on the rail line, Andrew quickly investigated and fired the culprits; a bit harsh on his part, which he soon realized. Now with a raised salary of $40 Andrew bought a commodious house in Altoona but before the family could move in, a tragedy occurred. On the second day of October in 1855, after struggling for seven years in the promised land, William, his father passed away a broken man. Poor Andy could not fulfill the promise of buying a carriage for his father. Andrew now stepped into his father’s shoes. Margaret still saving for the rainy day still mended shoes as his brother-young Tom, studied in a public school. Andrew found a father figure in Thomas Scott, who too loved Andy and taught him many valuable business lessons.

“Whatever I engage in, I must push inordinately.”

Fortune favors the brave and cowardice has no place in business! Once Scott informed Andrew of an investment opportunity of $500. Andrew had a savings of $50 only, and could only invest 50 cents. Margaret sensing a good opportunity mortgaged her home and Andrew invested in Adams Express. He received 10 shares, which paid a dividend of $10 in the very first month. He proudly showed the envelope bearing his name Mr. Andrew Carnegie, Esquire; to his friends. In 1856, Thomas Scott was promoted as General Superintendent of Altoona and by natural succession, Andrew now 21, became Superintendent of Pittsburg. Scott had lost his wife and become lonely, so he asked his Protégé to shift into his chambers. Thus Andrew spent a significant amount of time with his mentor.

Andrew with his newly bestowed powers dealt with workers on strike effectively and used corporate espionage to contain the eventuality of unjustified strikes. In order to cut costs, the wages of workers were slashed brutally, in-spite of working 13 hours a day. Expansion and innovations progressed during the same period. The credit of sleeping coaches in Trains also goes to Andrew Carnegie who sold the novel idea to his mentor. The company tied up with T.T. Woodruff a manufacturer of the “Sleeping Car”. In this venture, the manufacturer offered Andrew partnership. Andrew took a loan of $217 for their first order from the company, which turned out to be successful and he earned $5000 in profits.

Money is no good if you are poor intellectually. In 1859, Scott became Vice President of Pennsylvania Railroad and Andrew was appointed as the general superintendent of the Pittsburgh division with a whopping salary of $1500 a year. He moved from Altoona to Pittsburgh among his old relatives and friends. He appointed his younger brother Tom as his secretary. The Carnegies moved into a new commodious house in Homewood Estate – neighborhood of wealthy citizenry. In social gatherings and jamboree, Andrew hobnobbed with rich educated people. He realized a huge gulf between him and his highly educated peers. He polished himself in mannerisms and attire; he read English classics and literature.

Mostly dealing with uneducated labor, who shamelessly mouthed cuss words and appeared shabbily, Andrew found it less difficult while dining with the who’s who of Pittsburgh. He carried himself with panache and spoke charmingly.

In 1861 the civil war gave impetus to the Railroad business and other manufacturing units. During this period American business-houses made huge fortunes. Washington summoned Thomas Scott and Andrew Carnegie to be in charge of the Union’s transportation department. The job included to set up, manage and military railroad, and telegraph systems. The duo facilitated in organizing a working force for railway department. Andrew personally put his life in danger to transport soldiers and military hardware to the war regions. He also supervised the bushelling of tracks and telegraph lines.

Once while riding in the engine to bring back wounded soldiers to Washington, Andrew saw a telegraph wire pinned down under stakes of wood. He halted the train and started pulling out the wire, which sprang up and cut his cheeks, making him bleed profusely. Andrew Carnegie laid new tracks and communication system for the Union government during which time he got an opportunity to meet President Lincoln. Andrew Carnegie, was impressed by Lincoln’s mannerisms and tact in handling people, which he adopted wisely in the later years. He dined with General Grant, the civil war hero, who discussed his strategies with Andrew. Andrew was proud to serve the country, which gave him the opportunity to soar.

After doing his bit in the Civil War, Andrew returned to resume his duties at the Railroad. Soon after he was down with illness, and on doctor’s advice Andrew took a leave of absence from his office. Andrew went to Scotland for convalescing, with his mother and friend Tom Miller. The Carnegies reached Dunfermline on June 28, 1862 riding a carriage as promised by Andrew. As the carriage moved towards High Street, his mother’s eyes were filled with tears of joy. Even Andrew Carnegie was overwhelmed with joy; after all home is home. The reception of the Carnegie’s was more of a celebration.

Returning after 14 years, Andrew found everything in his old town Lilliputian, the well, the church, the school and the playground. He met his old relatives and friends, but his eyes searched for his mentor Uncle Lauder, who had not changed much. His holidays, were however cut-short, as he again fell ill and decided to leave for America, as Scottish traditional medicine was ineffective.

“Mr. Morgan buys his partners; I grow my own.”

During Civil War, prices of Iron were as high as $130 per ton, which during the pre-war era was twice lower. Post war, new infrastructure projects were initiated to connect the United States of America. The problem with wooden bridges was either they cracked or burned down in the scorching sun. Pennsylvania Railroad once built a small iron bridge which stood the test of time, successfully. Iron was the answer! Andrew realized the potential of iron bridges and started a business by forming an alliance with H. J. Linville, John L. Piper and Mr. Schiffler. The company was named Iron Bridge Company. It was the first company in America of its kind, which dealt in Iron bridges. Each partner invested $1250. Later Piper and & Schiffler merged their private company in this union and KEYSTONE BRIDGE COMPANY was formed in 1863.

The company undertook a project building a 300m long bridge made of iron. Where there is Innovation there is also speculations. Some believed bigger iron bridge won’t even stand its own weight, some concluded a running train will derail or the bridge will fall underneath. However, the quartet made their detractors eat humble pie after their pioneering projects. They even tried selling steel track to Railroads, but due to inflation, many Railroads rejected their ideas. While other bridges collapsed or cracked due to wind pressures and structural problems, the Keystones Bridges were the epitome of engineering excellence. The company used top class products, tools and labors for its undertaking. They even manufactured their own iron and ensured High-Quality. The company Declined to build unscientific bridges or bridges of poor quality. The policy served well for Andy, as he religiously believed in excellence. However, not an engineer himself, Andrew presented his ideas to his clients with conviction. The secret of his success was to put together a team of talented engineers with business acumen.

“It marks a big step in your development when you come to realize that other people can help you do a better job than you could do alone.

Andrew Carnegie formed Cyclops Mills in 1864 and three years later, in 1867, the Union Iron Mills. These factories were spread over 7 acres of land and manufactured Iron beams and other structural profiles, which no one in the industry dared to dream. He maintained his quality and retained his clients efficiently. He believed in settling disputes without a lawsuit. Andrew incorporated accounting system to control expenses and monitor profits and losses on daily basis. The perceptive businessman controlled the waste and invested heavily in modern machinery, ameliorating output.

Although he had too many irons in the fire, Andrew continued working at the Railroad but ensured his interest in all the ventures was undisturbed. Post civil war, the madness for black gold [oil] led Andrew to buy an active oilfield in Storey Farm with an investment of $40,000. The speculative oil business investment, earned Andrew millions in return. By the age of 30, Andrew earned $2400 a year. He resigned from the Railroad Company after taking the blessings of the President Mr. Thomson and his former mentor Scott. Andrew Carnegie never worked for a salary again; he no longer was a wage-slave.

In 1865 Andrew founded the Keystone Bridge Company with the intention of building bridges from Iron rather than wood. A couple of years later the Keystone Telegraph Company was founded, which in a short while tripled the investors returns.

“I shall argue that strong men, conversely, know when to compromise and that all principles can be compromised to serve a greater principle.”

In 1867, Andrew visited Europe along with his friends Henry Phipps and J.W. Vandevort. They travelled extensively and discovered newfangled methods of productions, which could be implemented in America. Passion of becoming master of his own fate made Andrew Carnegie to take huge risks. He recruited his cousin Dod son of Uncle Lauder (First Mentor) in his firm where his mechanical engineering skills aided the plant immensely. Lauder Jr. curbed wastes of the company and skyrocketed the production through his ingenuity. Dod was rewarded handsomely in the form of company shares.

Andrew established a coal washing factory and asked Lauder Jr. to settle in Pittsburgh permanently. He struck a 10-year contract from leading coke producers of the time. With the Railroad at his disposal for transferral at low tariff, Andrew Carnegie flourished. He erected 500 ovens, which washed 1500 tons of coal every day. With breathtaking innovations, the company even produced coke from waste, which a decade ago was thrown away as useless material. The art of making something out of nothing made the company, the first on the continent. Carnegie upgraded his iron-manufacturing units but secretly desired to venture into steel business. Due to unavailability of the technology in the country steel in those days was imported from England. Many American manufacturers also avoided trading in Steel due to heavy taxation policy in the country. Andrew lobbied aggressively to bring down tariff in manufacturing and transportation.

In 1867, Andrew along with Tom and his mother shifted to New York. The new bustling city was a fresh start for the family. For Andrew Carnegie it was a strategic move as the city was the financial capital of America. The family moved into the St. Nicholas Hotel and Andrew opened his office on Broad Street. Within a few months, they moved to the Plush Windsor Hotel. He socialized with affluent New Yorkers and was an active member of the 19th century club. He met many magnates, intellects even foreign ministers from Russia and Germany. The members at these gatherings discussed matters varying from “Economy” to “Politics”. It gave Andy opportunity to learn about new subjects and study them in deep. He gave speeches at the summits and was becoming a good rhetorician.

In 1868, 33-year-old Andy earned $50,000 a year; he was planning for an early retirement by 35. Until then he wanted to accumulate wealth and spend it on benevolent purposes. He desired to settle in Oxford and get thorough education. Andrew wanted to give special attention to public speaking and the improvement of the poor classes. Nevertheless, when Andrew read Herbert Spencer’s survival of the fittest theory, it again sparked the urge to earn money like never before.

“Think of yourself as on the threshold of unparalleled success. A whole, clear, glorious life lies before you. Achieve! Achieve.”

Andrew Carnegie repeated his childhood strategy, when he was pitching for the major sleeping car project form the Pennsylvania Railroad Company. His rival Mr. Pullman an experienced contractor also bid for the same. In a very bold move, Andrew approached Pullman and convinced him to form a partnership. When the latter asked, what will the company be called? Andrew promptly replied “The Pullman Palace Car Company”.

Andrew Carnegie’s partners seldom saw him boiling or stewing. For them he was an ocean of optimism, which never dried up. The sunshine boy of Dunfermline always laughed at his troubles. Andrew was well connected in his business circle. He had developed a knack of raising money for sinking companies, which later became his specialty. On numerous occasions, Andrew Carnegie was roped in by his partners and outsiders to formulate a “Bailout Plan” for the company. One such company was Union Pacific, which sold its rights to Pennsylvania Railroad for $600,000. Post the Bailout plan Andrew Became Director of the company along with Scott and Thomson. He held the shares in the vault and went to Europe to obtain capital for a bridge construction project in Missouri. On his return, he found Scott had sold their bonds, for huge profit but it ended their control in Union Pacific, which would have yielded a fortune in the years to come.

The incident strained the relationship between Scott and his protégé Andrew Carnegie.

In 1870 one of Andrew’s friends introduced him to 21 year old Louise Whitfield who was the daughter of a wealthy merchant. He began calling on their home and this continued for almost a decade. He began courting her from 1880 onwards until he finally tied the knot in 1887.

“The way to become rich is to put all your eggs in one basket and then watch that basket.”

Andrew was tempted to join the finance sector but his first love was manufacturing tangible commodities. He got ample opportunities to become a part of many lucrative businesses, but he stuck to his main business Iron. From wrought iron to pig iron, the company made different varieties. With the rising demands of growing America, Andrew built Lucy furnace in 1870, which produced 100 tons of steel per day. The feat was an Industrial marvel. The company adopted scientific methods for production and Andrew was always open for suggestions. Innovation is the key for any business and for Andrew Carnegie it was a ritual. He believed in delegation of work for smooth daily operations. He hired foreign chemists who analyzed ironstone to cut wastage of time and fuel. It led to scientifically backed revolutionary changes. Andrew’s modus operandi helped cut down future losses, which his competitors considered extravagant spending.

Andrew Carnegie could foresee that Iron Age was over and steel age was to begin. By 1872, Andrew dedicated himself to manufacturing Bessemer Steel, made from an innovative method.

The great depression of 1873 tested the friendship of Andrew Carnegie to Thomas Scott. Scott had invested heavily in Texas Pacific Railway and lost his entire fortune. He turned to his son like protégé for yeoman’s service Andrew Carnegie refused it flatly. Andrew stuck to a solitary policy when it came to financial help:

Are you capable of taking or lending, a loan? Is taking risk for your friend worth it?

**Scott died as a broken man in 1881.

Andrew survived the financial crisis due to his money saving nature. The company’s policy was against extravagant spending or to invest in any other iron and steel company or companies in debt. Mr. Kloman one of the partners with Andrew Carnegie lost money in such a manner and was ousted. It was the survival of the fittest!

In 1875, Andrew, in flattering move formed Edgar Thomson Steel Co. In the name of his former boss and President of Pennsylvania Railroad. This move made Andrew the sole manufacturer for the railroad’s steel requirement. E. T. Steel Co’s first order was 2000 Steel rails for the Pennsylvania Railroad.

Acknowledging the opportunity in the Steel business, Andrew built Union Iron and Steel Company. The conglomerate‘s Steel Rail Mill manufactured only railway equipment. Andrew also supplied Iron and Steel for Keystone Bridge Company of which he held a major stake. Always ready for the gauntlet, Carnegie invested heavily in rival railroad companies and threatened the owner to lend him a bigger share or he would wipe them off from the industry. Perspicacious Andrew examined his rival’s financial statements and knew their costs and his. No one could dare to compete with him in the steel business. Although he was based in New York, he demanded the daily transaction reports from his accountants based in Pittsburgh factory. Accounting and production output was monitored day by day and penny by penny. He told his managers to watch cost and profits will take care of itself. He inspired managers and engaged his workers in healthy competitions in the factory.

If managers or work crew lagged behind they would be fired without prior notice. The workers worked 12 hours a day and 7 days a week except on 4th July. The dehumanizing conditions often created conflict between workers unions and management. The puddlers (a worker who turns pig iron into wrought iron) who in the pre-industrialization era were considered as craftsmen were now facing the danger of being laid off. The daunting machinery of the industrial revolution swallowed the jobs of these highly skilled labors as it did to William Carnegie decades ago. The iron to steel age came at a human cost, but Andrew Carnegie was unmoved, as he could foresee the revolution and harnessed the technology.

Andrew Carnegie was considered audacious, belligerent, reckless and a shrewd businessman. Many industry speculators and competitors considered him doomed to failure. Only the near and dear ones knew about him. He was considerate and patiently heard out his manager's pleadings. If certain ideas at the plant did not work out, he would ask managers to uproot the installations and start all over again. His innovative ideas enhanced the production resulting in high grade quality steel at an affordable price. Above all, it ended the country’s dependency on foreign manufacturers. On numerous occasions, Andrew Carnegie offered partnership to his key employees, who went on to make millions in the coming years.

With his work obligations in order, Andrew started dating Louise a bright polite daughter of a wealthy merchant of New York. The couple rode together in New York Central Park and met often at club gatherings. He wrote to her often when he went on a Round-the-world trip in 1878. Andrew visited different countries and learnt about their religions. In China–Confucius, India–Hinduism and Buddhism; he even visited Bombay and met Parsi’s and learnt about Zoroaster. Andrew Carnegie had achieved mental peace; his mind after years of gruesome struggle was at rest. The world tour from Calcutta to Melbourne and Singapore to Arctic Circle evoked his philosophical and spiritual side. Andrew was filled with contentment.

On his second trip to Scotland in 1881, Andrew Carnegie donated a library to Dunfermline and his mother laid the foundation. He wanted Louise to accompany them in the jaunt but her mother never allowed it. In 1886 Andrew suffered from Typhoid, he was on a bed rest; next-door his mother too was sick with pneumonia. Unfortunately, Andrew’s younger brother Tom too had taken to bed, due to alcohol abuse and died in the October of 1886. Andrew was too weak to attend his funeral. A month had just passed when Margaret his mother too left for the heavenly abode. Her coffin was lowered secretly from the window so that Andrew would not know about the tragedy. The tycoon himself was in a delicate condition; Andrew was informed a week later, which left him devastated.

For the very first time Andrew shed tears, he was a broken man, lonely like as a street Arab. His mother was the centre of his universe, he had amassed huge wealth only to see mother ride in carriages and dress in best silk gowns. But soon he recouped.

In 1888, Andrew Carnegie purchased a sick steel enterprise of Homestead at a handsome price. Homestead was famous for making structural beams used in skyscrapers and armor plates for the Navy Ships. However, the workers were notoriously famous for indefinite strikes and mob justice, which led its previous owners to sell off the company. Within the first week, Andrew realized he wanted a muscle to run this facility. Obstreperous Henry Clay Frick was just right man for this position. Andrew met Frick at New York’s Windsor hotel and invited him for the dinner. At the end of the dinner, Andrew offered Frick a position of Chief Executive of his Homestead Plant. He was a businessman and an owner of the Frick Coke Company. Driven by money and power, Frick agreed to join hands with the iron and steel Tycoon. In return, he guaranteed access to his vast supply of coke, which is a key ingredient in making Iron, and without Iron, there, is no steel!

“And while the law of competition may be sometimes hard for the individual, it is best for the race because it ensures the survival of the fittest in every department.”

The Titans of the gilded age made fortunes by monopolizing their respected Industry like John D. Rockefeller, J.P. Morgan and Andrew Carnegie was no exception. Their temerity made them the juggernaut in the annals of American business.

With Frick at his disposal to undertake dirty works, Andrew led an assault on his competitors who sold better steel at cheap prices. The giant company soon started feeling the pinch as one by one they lost key contracts from the railways. Defying the spirit of Laissez-faire, Frick would often intimidate his competitors to surrender their business or would bribe the foreman to call for strikes. The next move, which Andrew and Frick orchestrated, is a classic example of business deception. The company started writing letters to Railroads, claiming the steel their company purchased from the competitors was dangerous as it lacked “Homogeneity”. A fictitious component Andrew coined to scare-off the Railroads. The strategy worked and the competitors lost their contract and filed for bankruptcy. Then with a swift move, Andrew would scoop up his rival’s company adding new technology and an asset to his iron and steel portfolio.

“A man who acquires the ability to take full possession of his own mind may take possession of anything else to which he is justly entitled.”

Frick single handedly, had doubled Andrew Carnegie’s profit, while working as his manager at Homestead and Chief Executive of his Steel Business. With operations under the control, Andrew channelized his efforts in buying companies and Iron mines. He purchased shares of the Frick Coke Company and became its owner. In the next 10 years, the company grew three times its size. Andrew invested nearly 20 million dollars which doubled by 1897. The result was an enormous growth. The company was earning enormous profits but when shareholders demanded dividends, Andrew refused as he reinvested the profits into the company. He built his private railway to transport coal and steel. He built a giant lake boat for the same. Lowering the prices of his steel, Carnegie knocked his competition.

Though Andrew Carnegie was flourishing, it silently wrote the darkest chapter in American labor history. Andrew’s ruthlessness in his dealing led to ethics taking a back seat. Carnegie’s most profitable Edward Thomson Steel Factory came to a sudden halt, when union workers demanded better salaries and working conditions. Instead of bowing down to their requests, Andrew ordered his managers to shut down operation. Weeks later, some representatives of the workers came to visit Carnegie in New York. He welcomed his workers warmly, took them around the city, wined, and dined them. Never once did Carnegie ask them the purpose of their visit and treated them in the best possible manner. The representatives went back and the strike ended without further delay.

“As I grow older, I pay less attention to what men say. I just watch what they do.”

Under the impression that strikes were a thing of the past, Frick woke up to the news of his workers going on strike at his southwestern Pennsylvania coke factory. He fired the workers and replaced them with non-speaking European labors, but soon they demanded better wages. When Frick turned down their proposal, the hostile labors burned down property in his factory. Maddened Frick hired a private agency called Pinkertons who provided the security for the company. The matters were resolved and the factory was back in business. He crushed the worker unions at his company.

Fresh tensions now brew at the Homestead Mills, in the recently upgraded facility with modernized furnaces and equipment. Naturally, the owners were obliged to downsize its workforce and slash the remainders salary. It was in the year 1892, and the workers Union contract of 3 years was about to expire. Frick saw an opportunity to do away with the union rats for good and denied renewals. The workers were left unemployed. Taking lessons from his coke mill devastation, Frick built an 11 feet high wall around the company’s property to keep it safe from the rioters. The workers named it “Fort Frick”. Facing resistance from the Union workers for bringing a new workforce, the factory finally was locked out. More than 2400 workers went on strike, as Frick declared that he will not tolerate Unions in his mills and will make a contract with workers individually. At the time, Andrew had left for Scotland for his vacation, putting Frick in charge of operations. The incident got enough media attention. Once again, Frick hired Pinkertons to crush the rogue workers. More than 300 armed Pinkertons landed on the shores of Homestead. A fight broke out; soon the Pinkertons were outdone and outnumbered by the humble workers carrying clubs, pipes and handguns. The 14 hours of gunfight resulted in three deaths of detectives and nine workers or their supporters. The mayor of homestead had to intervene and the militia was sent to curb the situation. There was a huge uproar in the public over the incident. Andrew Carnegie’s public image was shattered.

“Do real and permanent good in this world.”

It was the year 1894; the Ghost of Homestead still haunted Andrew Carnegie. Media and public stated that Andrew Carnegie acted in a cowardly fashion; some went further to state that he was a hypocrite as on one side, he donated libraries and on the other, he bled humble workers to death. The situation could have been avoided, if Andrew had dealt with the Homestead workers in his trademark fashion. But as fate would have it, the union was abolished and there was no workers Union for the next 45 years. The homestead workers were forced out of their homes and the instigators of the strike were blacklisted in the entire industry. Andrew Carnegie’s relation with Frick was now strained as the former gave interviews to journalists claiming that Frick was solely responsible for the whole episode. Frick planned for a hostile takeover of the company, but before his idea took shape, he was ousted from the company.

Andrew Carnegie’s Iron and Steel Company was big enough to sustain growth without Frick. By 1900, the company produced more Iron and Steel than Great Britain’s entire industry. Homestead was a major blow to Andrew Carnegie, and until his last breath, he denied his involvement in the incident. To win back the confidence of his workers, the standard working time was reduced from 12 hours to eight with weekends off. He now treated the workers fairly, provided them with savings account at 6% interest and co-operative stores so that the workers could buy cheap groceries for their family.

“The man who dies rich, dies disgraced.”

At the age of 65, Andrew wanted to spend more time with wife and daughter Margaret. He stopped accumulating and started systematic distribution. In 1901, Andrew Carnegie, with the help of trusted partner Charles Schwab sold the business to J.P Morgan for $480 million becoming the world’s richest man.

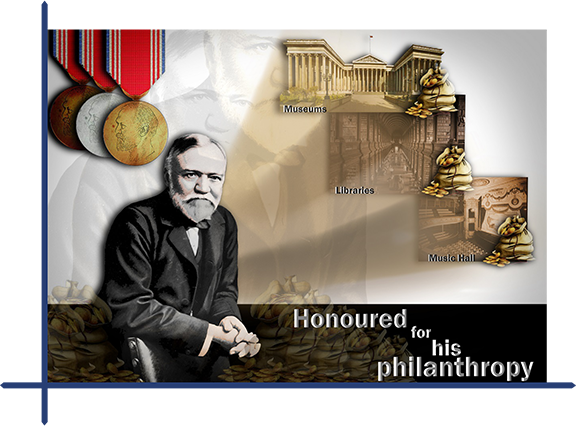

Spending more than $350 million on his philanthropy, he formed a Medical and Old age aid, gave millions to maintain libraries, music Hall and museums. Andrew Carnegie formed a relief fund for Iron and steel workers.

He built technical colleges and Carnegie Institute of Washington and Pittsburgh. The astronomy observatories were built for scientific breakthroughs. He started Hero Fund in Germany, England, France, Italy, Belgium, Holland, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and Denmark. Millions were spent on pension fund for retired college professors. He donated organs to churches. In his remaining years, Andrew Carnegie finished his autobiography and worked relentlessly towards disarmament and world peace. On August 11, 1919, the steel tycoon breathed his last at Lenox, Massachusetts, fighting bronchial pneumonia. He did not die disgraced.

Aim for the highest

The wealth distributed by the Carnegie foundation strengthened the future of America through education. Over the years, the Carnegie Institutions spread across the nation, have produced many eminent scientists, engineers and Nobel laureates. The hard-earned money provided shelter to homeless individuals and supper to the famished. His riches brought smiles on the faces of those miserable and clothed the au naturel bodies. His illustrious life is an example that one individual can bring in the change. Chasing the riches and acquiring it will not be gratifying as using it for benevolent purposes. Twenty first century Billionaires have realized the power of wealth and it is no surprise that many are ready to give away their entire fortunes for the upliftment of hapless souls.

We come and go empty handed; the fortune you made won’t be buried or cremated along with you. Spend the money to spread the joy.

Next Biography