Introduction

In 1883, Friedrich Engels in his eulogy to his dear friend and colleague said, “On the 14th of March, at a quarter to three in the afternoon, the greatest living thinker ceased to think. He had been left alone for scarcely two minutes, and when we came back we found him in his armchair, peacefully gone to sleep – but forever.”

These words of Engels exemplify the intellect and persona and provide a glimpse into the life of the greatest economic theorist of the 19th century, Karl Marx.

Marx adorned many hats, being a philosopher, economist, journalist and sociologist who tremendously contributed to the development of the political and economic scenario for the years that followed. His funeral saw a congregation of only 11, but his ideology became the foundation of many. He co-founded the Theory of Marxism with his lifelong friend and colleague, Friedrich Engels and his revolutionary thinking was then adopted by many influential leaders, taking the form of a political change all over the world.

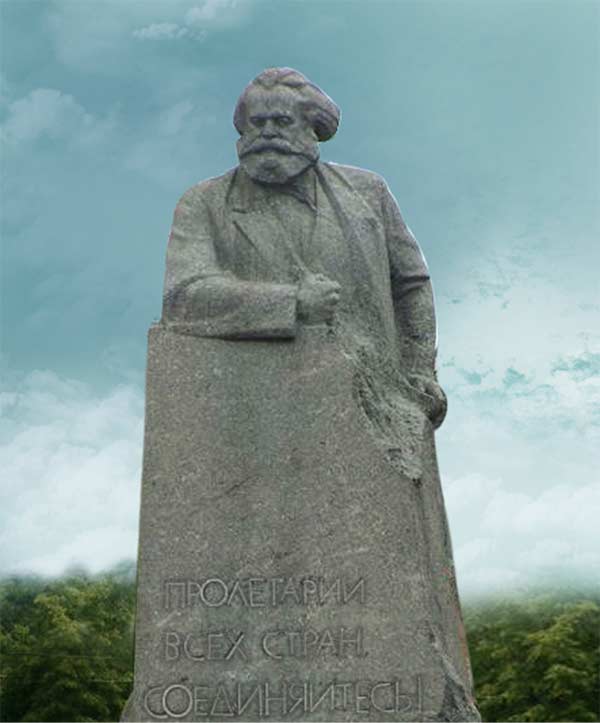

In the eulogy, Engels went on to say, “Just as Darwin discovered the law of development of organic nature, so Marx discovered the law of development of human history”. He added, "His name will endure through the ages, and so also will his work." Engels predicted correct as even 129 years after his death, the writings of the father of Communism were the foundation for many theorists and influenced many political giants of the 20th century. Friedrich Engels’ eulogy immortalizes and celebrates the life of Karl Marx who sowed the seeds of his ideologies in the 19th century but its impact travels through time and is still prevalent in the 21st century. Marx worked for liberation of the proletariat from the vicious clutches of the bourgeois society. His outlook saw the light of day and gathered recognition in one of his formative works, ‘The Communist Manifesto’ which he co-authored with Friedrich Engels. This is till-date considered to be one of his most riveting and influential works and his last words of that manifesto, “Working men of all countries, UNITE!” are forever engraved on the minds of the people.

Roots of Marx’s being

Founded in 16 BC, Trier (French ‘Treves’) is one of the oldest cities in Germany and is situated on the banks of the river Moselle. The city was of great importance to the Holy Roman Empire and great wars were fought on its soil during the 1600’s and 1700’s. In the 1600’s, the city of Trier was occupied by French troops and this acquisition continued for quite some time. The French troops besieged Trier in the year 1632, 1645 and 1673, after which began the destruction and mutilation of the churches and abbeys for military reason. In the years that followed, even more wars were fought on the grounds of Trier as it became the frontier of the religious and political scenario. In 1801, Napoleon Bonaparte signed the agreement with Pope Pius VII, putting an end to the defamation caused to the clerics and making Trier a diocese. Under the leadership of France, Trier began to prosper and then, the French reign ended in 1814 with the sudden acquisition by the Prussia troops. Napoleon was defeated at Waterloo in 1815 and Trier was now part of the Kingdom of Prussia (The Prussian Rhineland).

Prussia was a Christian state and its churches were answerable to its political leadership. The 1812 decree passed by the Prussian authorities stated that the Jews were not to hold any legal or state positions. The conservative control of the Prussian authorities led to a number of irrelevant laws being enforced. Herschel Mordechai Marx, born on 15th April, 1777, lived in the city of Trier during this time of turmoil. He was a Jew and the son of a Rabbi (a Jewish individual who is trained and ordained to perform religious ceremonies and could lead a Jewish congregation). Later, his elder brother Samuel followed in his father’s footsteps. Herschel descended from a family of Rabbis but studied and practiced Law. The situation in the Prussian Rhineland at that point of time was changing into an anti-Semitic society. An inferior status had been bestowed upon the Jews and they were not allowed to hold legal positions. Herschel made many efforts to keep his professional post, but his pleas were rejected.

The uneasy situation for the Jews in Trier which was part of the Prussian kingdom, led to Herschel converting to the protestant Christian sect of Lutheranism in 1817. In his attempts to delete all recognizable ties of him being a Jew, he also changed his name from Herschel Mordechai Marx to Heinrich Marx, a common German first name. This allowed him the opportunity to practice his profession and lead a normal life. During these trying times, Heinrich Marx was supported by his wife Henrietta Pressburg, whom he married on 22nd November, 1814. The family had lived a very bourgeois lifestyle and sticking to their Jewish traditions and way of living would have only caused them the havoc of losing that position in society.

Heinrich Marx was a Prussian loyalist and a learned individual who had an inclination towards the writings of great philosophers like Immanuel Kant and Voltaire. Henrietta Pressburg, on the other hand was a Dutch Jew, born on 20th September, 1788, in Netherlands. She belonged to a wealthy and prosperous business family and had familial connections with Philips Electronics. She was the great aunt of the founders, Anton and Gerald Philips. After their marriage, Heinrich and Henrietta started their family and were the parents of eight children - Sophie, Karl, Hermann, Henriette, Louise, Emilie, Caroline and Edward. Henrietta believed in smothering her family with too much love and affection. Unlike her husband, Henrietta was not highly educated but she did have a rabbinical background like Heinrich, with her father being a Rabbi in Nijmegen, a city located in the east of Netherlands, near the German border.

Karl was the second child and eldest son of Heinrich and Henriettad. He was born in the wee hours of the morning of 5th May, 1818. He was baptized into Lutheranism in the year 1824, at the age of six. Information and personal incidents about Karl’s childhood seem to be a blur, but many of his relatives would call him a tyrant who would bully his younger sisters with his mischievous deeds. But Karl was not all mischief. From that very young age he displayed qualities of being a story teller of epic proportions. He also suffered from a noticeable lisp, but that did not hamper his speech abilities to a great extent.

Karl’s parents recognized his intellect and abilities and expected great achievements from him. The two were very fond of their eldest son, but Heinrich harbored certain apprehensions. He feared ‘the demon’ that Karl was sheltering within himself. Karl, unlike his peers of that time was cold and oblivious in character, which was a change in comparison to the yielding nature of the other members of the Marx family.

Academic Influence

Karl Marx was educated at home till the age of 13 and in the year 1830 he was enrolled for his preparatory education at Trier High School. The headmaster of the school was a friend of Heinrich Marx who appointed liberal individuals as school teachers. Karl intended to learn Literature and Philosophy, but his father Heinrich did not agree with him as he thought Karl would be unable to support his future as an academician and therefore asked him to pursue a career in Law instead. Taking note of his father’s suggestion, at the age of 17, Karl then ascended to the University of Bonn in the autumn of 1835, where he spent a year studying Law, but could not garner any great interest in the subject. During this period, he also learnt about Greek and Roman mythology and displayed great interest in learning the history of art.

By the time Karl reached the age of 18, he suffered from a weak chest and his incessant smoking and drinking added to the trouble and therefore he was deferred from being enrolled in military service. Karl’s reckless attitude began to surface when he sang, drank and dueled through his days at Bonn. He would get intoxicated and misbehave. While he was at the University of Bonn, he became part of the Trier Tavern Club drinking society and for a small period also served as its co-president. His frivolously carefree lifestyle caused him to end up in severe debt and numerous brawls and his university grades were a reflection of this irresponsible behaviour. Karl’s activities left his father Heinrich troubled, as the number of scuffles he engaged in kept increasing over time. It was from here that Karl showcased the streak of his rebellion and the future of him being constantly in debts. His father was distressed by Karl’s behaviour and therefore asked him to shift to an academically more serious university.

The University of Berlin was known to garner very little attention when it came to extra-curricular activities. Philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach, a former student, described it saying, “In no other university can you find such a passion for work… Compared to this temple of work, the other universities are like public houses.” Heinrich was very inclined for Karl to study at the University of Berlin and asked him to shift there to divert his mind from the many distractions in his life, but by then Karl had found a new interest. He had fallen in love with Jenny Von Westphalen.

Johanna Bertha Julie Jenny von Westphalen, fondly called Jenny, was the daughter of an aristocrat Baron Ludwig Von Westphalen, a senior official of the Prussian Government. Karl shared a very cordial relationship with the Baron and it was he who introduced him to Philosophy and Romantic Literature. Ludwig was an aristocrat who detested the Prussian scenario and political way of thinking. His daughter, Jenny Von Westphalen, was a girl of extraordinary beauty and character. She was said to be the most beautiful girl in Trier. “Angel girl” and “The Enchantress” were couple of titles bestowed upon her. She was four years senior to Karl and courted with him, paying no heed to the highly influential and innumerable prospects who adored her. She even broke her engagement with a young second lieutenant as she fell in love with Karl. Karl on the other hand, was a former Jew and the God of good looks did not favour him very much. He also had considerably lesser wealth as compared to the Westphalen’s. Karl was a stubborn, intelligent but a rather rebellious individual, whereas Jenny was a soft spoken girl with an aristocratic upbringing. Jenny detested the wealthy and uptight lifestyle and found it claustrophobic and suffocating. She also found Karl’s intellect irresistible. Her involvement with Karl brought her the opportunity to break away from the clutches of the aristocracies, and the two were secretly engaged by the summer of 1836. The union of Jenny and Karl was a scandalous affair as it broke two of the prevalent social taboos, that of the marriage of a woman with noble background with a man of Jewish origins and the union between a member of aristocracy with that of a member of the middle class.

The period when Karl and Jenny were engaged, Karl was 18 and Jenny 22. The engagement was a secret affair and Jenny’s family was kept unaware of it, but Karl could not keep within himself the joy of being engaged to her and kept boasting to his parents. Jenny was the fairy Princess, whereas Karl’s appearance on the other hand was that of an unattractive exterior but he exuded exceptional intellect and character.

In the year 1836, Karl received admission in the University of Berlin where he went on to continue his education in Law and Philosophy. The University of Berlin was also one of the strongholds of Hegelian ideologies as Georg Friedrich Wilhelm Hegel was previously holding the Chair of Philosophy. He was seated at the designation for approximately 13 years. Five years later when Karl arrived, the Hegelian ideologies still had a strong grip and Karl was greatly influenced by his works.

Hegelianism as a system of thought focused on history and logic. A history that saw in varied perspectives that ‘the rational is the real’ and through logic it saw that ‘the truth is the whole’. Hegel’s school of thought was divided into three groups: the ‘Hegel Right’ or ‘Old Hegelians’ that believed and defended Hegelianism, taking it in the direction of political and religious conservation; the central group of followers who preferred to retreat to analysis and interpretations of the Hegelian system in its genesis and significance and the third group, the ‘Left Hegelians’ or the ‘Young Hegelians’ who interpreted Hegel’s philosophy by identifying the rational with the real in a revolutionary sense and supported innovations in politics and religion.

In Berlin, Karl became a part of the ‘Young Hegelians’ who met on a regular basis and discussed leftist ideas. The group included Ludwig Feuerbach (German philosopher and anthropologist), Arnold Ruge (German philosopher, socialist revolutionary and political writer) and Bruno Bauer (German philosopher and historian, who was a lecturer in theology at the University of Bonn). His mind was then also influenced by people of many varied backgrounds like writers, liberals, conservatives, journalists, believers and non-believers.

While studying at Berlin, Karl wrote a letter to his father mentioning that “he suffered from intense vexation at having to make an idol of a view I detested” and later found Hegel’s doctrines disreputable. Karl was very critical of Hegel’s ideology but in order to criticize the existing society, religion and politics, he adopted the dialectical method of his theories (The process of arriving at the truth by stating a thesis, developing a contradicting antithesis and combining and resolving them into a coherent synthesis). In the years that followed, Karl showcased keen interest in his criticism of Hegel and his radical Young Hegelians mates. The ‘Young Hegelians’ were his first acquaintance with radical thought and this was one of the first encounters he had with what the future had in store for him.

It was one of the most crucial and personality altering, rather, personality forming experiences of his life. Members of the Young Hegelians were much elder to Karl, but he displayed an intellect far forward of his age.

With him growing out of the boundaries of conventional thinking, Karl lost interest in his law pursuits at Berlin and became more inclined towards philosophy. He became keenly interested in the works of Aristotle (a Greek philosopher and polymath), Francis Bacon (an English philosopher, statesman, scientist and jurist), Baruch Spinoza (a Jewish-Dutch philosopher) and other great philosophers. During these years, Karl also tried his hands at writing and wrote a couple of short novels and dramas in fiction as well as non-fiction. In the year 1837, Marx completed the novel ‘Scorpion and Felix’ and a drama called ‘Oulanem’, which is an anagram for ‘Manuelo’, a variant of the name ‘Emmanuel’ meaning ‘God with us’. However, his works got misplaced somehow and saw the light of day only 134 years later when Robert Payne, the famous author published the one act play, ‘Oulanem’.

On the personal front, with the age gap between Karl and Jenny, her family was anxious for her to be married at the earliest. However, Karl needed time to complete his education, but seeing the situation on Jenny’s end, he wrote to her parents about their brewing romance and their intention to get married. But then circumstances suddenly grew unfavourable, when on 10th May, 1838, Karl’s father passed away. Heinrich was the pillar of the family and after his death the family began to suffer emotional and financial instability.

Meanwhile, the time for Karl to submit his dissertation had arrived, but as being part of the Young Hegelians and their radical thoughts and outlooks, it was said, that his dissertation would garner contempt in Berlin. So, Karl sent his dissertation to the University of Jena on the topic, ‘The difference between the natural philosophies of Democritus and the Epicureans’. The University of Jena was very lenient and liberal when it came to education and showcased a readiness at giving away Doctorates. Karl then received his diploma from the University of Jena dated 15th April, 1841. His educational years had now come to an end at the age of 23.

Bad news visited him in 1842 when Bruno Bauer who Karl interacted with while being part of the Young Hegelians, was dismissed from the university, for his radical activities. With his expulsion, sank the dreams of Karl teaching at the university with Bauer. The same year, Karl’s journey of political involvement began and he moved to Cologne where he wrote his first article for the newspaper ‘The Rheinische Zeitung’. He then went on to write many thought provoking articles for the newspaper after which he was offered the post of an editor. On October 15th, 1842, at the age of 25, Karl accepted the post and The Rheinische Zeitung powered on an intellectual conquest under his editorship. During Karl’s professional tenure, his works were inclined towards social problems, due to which the paper was charged of encouraging and propagating communism.

Despite the many charges and allegations, the paper made immense progress under Karl’s leadership. The newspaper published many volatile articles and on 4th January, 1843, it published an anti-Russian article. The article created quite a row and on 21st January, the Prussian authorities, concerned about press censorship decided to suspend The Rheinische Zeitung. The government accused the newspaper of slander and inappropriate allegations against the state authorities and ordered its operations to be suspended. A political cartoon of Karl Marx was published around the same time, which depicted Karl as Prometheus (a cultural hero in Greek Mythology who was credited for creating man from clay and the theft of fire for the betterment of human progress and civilization). In the image, Karl was shown chained to a printing press while an eagle was depicted pecking at his liver. The eagle was used by the artist as a metaphor to display the censorship of the Prussian authorities and the figures at the bottom of the image that were pleading for mercy were the citizens of Rhineland.

While all these tribulations were troubling Karl, he grew distant from his family. With the death of Karl’s father, the familial relations between the Marx’s and the Westphalen’s began to strain. Jenny’s father, Ludwig Von Westphalen, was another binding factor to their relationship, but with his death on 3rd March, 1842 the awkwardness and hostilities between the two families became evident. The love between the two however, empowered all the difficulties and at the age of 26, Herr Karl Marx married Fraulien Johanna Bertha Julie Jenny von Westphalen on June 19th, 1843.

After their marriage, the couple spent many months living at the Westphalen House and then decided to move to Paris by the September of 1843.

Riveting Theories

After The Rheinische Zeitung was banned, Karl began to write for the Deutsche-Französische Jahrbücher (German-French Annals) which had been set up by Arnold Ruge. The newspaper had been setup as a reaction to the suspension of The Rheinische Zeitung in March 1843. The paper had its base not in Germany, but in Paris, the capital of the neighbouring France. It criticized enormously the censorship instructions which were issued by the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV. The journal also included the satirical odes of Heinrich Heine (German poet, journalist and essayist). One of the most famous and frequently used phrases of Karl printed in the journal was published in the ‘Introduction to a Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right’, which stated "Die Religion... ist das Opium des Volkes" translating to “Religion is the Opium of the masses.” Karl’s interest in politics kept growing and he continued his quest of understanding the society and class struggles. Shortly after, the authorities came down on the newspaper, closing it down. Karl was left without a job once again, but he never let it stop him from pursuing what he intended to write about. At times, he would dedicate himself for endless days to work, paying very little attention to food, interaction and cleanliness. He would sit at his desk completing his works through the night, and sleep on the couch to catch a few hours of sleep and then get back to work again. His ethic towards his work was worth being commended and his dedication was seen through his works. In the same year of 1843, Karl completed the book, “On the Jewish Question” in which he closely examined the part religious practices played in the society and day-to-day life.

On 1st May, 1844, Karl became the father of a daughter who was then christened Jenny Caroline, in honour of her mother, and was fondly called ‘Jennychen’. It was in the same year that Karl met with Friedrich Engels on 28th August. Friedrich Engels was the son of a German cotton merchant and unlike Karl, he had grown up in a modern and industrial environment. Engels worked in his father’s business giving up his educational pursuits towards Law. The two struck a chord and shared a friendship that lasted their lifetimes. They then began working on a book called ‘The Holy Family’ wherein they openly criticized the ideas of Karl’s former friend and colleague Bruno Bauer. The book got published in 1845. During his stay in Paris, Karl wrote many manuscripts and polemics like ‘The Economic and Philosophical Manuscript’ and ‘Theses on Feuerbach’ (a critique of the ideas of the Young Hegelian, Ludwig Feuerbach). In the latter, Karl famously stated, “The Philosophers have only interpreted the world, the point is to change it.”

Karl stayed in Paris for more than a year during which he wrote for the German newspaper ‘Vowarts’ which was published in Paris and had its connections with radical socialists of the Christian communist group ‘The League of the Just’. The radical writings and reviews of the newspaper garnered a lot of criticism and opposition from authorities, especially the article written by Karl, titled, ‘Critical Marginal Notes’ on ‘The King of Prussia and Social reform’ because of which, the Prussian king requested the French government to shut down ‘Vowarts’. Poverty then began to creep in, as Karl was unable to hold a job and there was no fixed form of income. To add to his troubles, Karl was expelled from France on January 16th, 1845.

In search of a new place now, Karl moved to Brussels, Belgium by early February and his family joined him there by mid-February. He was given the permission to stay in Brussels under the condition that he would avoid speaking on the current political situations. But Karl being Karl, he maintained an association with the radical thinkers, Belgian democrats and exiled socialists who included Moses Hess (Jewish Philosopher and Socialist) and Joseph Weydemeyer (Prussian communist journalist and politician). On the other hand, the friendship between Engels and Karl was growing from strength to strength and soon after Karl left for Brussels, Engels followed. The two then travelled to Britain, visiting many libraries in London and studying the economic and the political state of the working class. They also used the opportunity to meet with many leaders of the Chartist movement (The political reform movement in Britain) and the heads of the communities of the ‘League of the Just’.

By September 26, 1845, at the age of 27, Karl became the father of another girl named Laura. The same year he collaborated with Engels to write a book on historical materialism, titled ‘The German Ideology’. In the book, he criticized the thoughts of Bruno Bauer, Ludwig Feuerbach and Max Stirner (German philosopher and one of the significant individuals in existentialism, nihilism and post-modernization). The German Ideology was then followed by ‘The Poverty of Philosophy’ in 1847, which was a critical take on the socialist thought of French politician, philosopher, economist and socialist, Pierre Joseph Proudhon’s, “The Philosophy of Poverty.” His work was published in French and was considered a grand success. Vladimir Lenin (Russian communist, political theorist and leader) later said it was one of the first works of mature Karlism. The same year of the publication of ‘The Poverty of Philosophy’, Karl’s first son, Edgar was born on 12th February, 1847. Also, correspondence between the ‘League of the Just’ and Karl and Engels began. They received a proposal to join the group, which they accepted. By the June of 1847, the ‘League of the Just’ laid its foundation for a new ideological approach and was renamed ‘The Communist League’. Engels was part of the session that happened in London and was also an important member who helped draw up the new regulations. He and Karl then began working on one of the most famous and significant works of their life, the political pamphlet, more commonly known as ‘The Communist Manifesto’.

Published on 21st February, 1848, The Communist Manifesto was the first document of scientific communism and formed the basis of ‘The Communist League’s’ purpose. It began with the line, “The history of all existing societies is the history of class struggles,” further explaining the different class struggles and problems related to Capitalism and also the growing differences between the Bourgeoisie and the Proletariat. The Communist Manifesto concluded with the words, “Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communist Revolution. The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win. Working men of all countries, Unite!” The Manifesto re-sounded the words and struggles of the working class and gathered them to unite and fight against the vicious clutches of the bourgeoisie and capitalism. Engels mentioned that he had a share in the foundation of the theory (Karlism), but a great part of its principles belonged to Karl. He added, “Marx was a genius; we others were at best talented. Without him the theory would not be by far what it is today.”

During the same time, a revolution began to erupt in France, and Europe was engulfed by protests, rebellion and demonstrations. The Revolutions of 1848 brought before France the overthrow of the monarchy and the formation of the France Second Republic (The republican government between the 1848 revolution and the overthrow by Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, began the Second French Empire). Karl was said to have assisted in the revolutionary activities and was therefore arrested. The eye of suspicion began to roll on Karl and he was ordered by the King of Belgium to leave within the next 24 hours, after which he found his next nest in Cologne, Germany.

Before heading for Cologne, Karl settled in Paris for a short period of time, where he was instructed to set the foundation and central authority of The Communist League after its dissolution in Brussels. He was also asked to setup the German Workers club. Moving forward to Cologne by the 1st of June, 1848, Karl then started the publication of the ‘Neue Rheinische Zeitung’ (New Rheinische Newspaper).

The revolution on the other hand was emerging all over Europe, with unrest growing in places like Vienna, Hungary and Berlin. However, the loyalties Engels felt towards Karl were noticeable when again he arrived in Cologne. The Neue Rheinische Zeitung was first published on 1st June and Engels and Karl began to work in the post of editor and co-editor. The two used the newspaper as their medium to express their views on class struggles, rising of the proletariat and national liberation. Karl then ascended to being editor of the paper and he, along with many other revolutionary socialists working for the newspaper, began to face various allegations and were brought to trial many a times.

With time passing by and Karl’s communist and leftist thoughts being published in The Neue Rheinische Zeitung, it created a difficult situation for him to continue living in Cologne and he was then ordered to leave the country on 16th May, 1849. Karl then moved back to Paris as a major revolutionary outburst was expected. A change in place brought only more instability and uncertainty to life. Adding to his grief and trouble, very soon Karl was expelled from Paris also, as he was considered a political threat. On the other hand, his wife Jenny was expecting for the fourth time, but Karl had no safe place to go. He had been expelled from Germany and Belgium. He had three children and a wife to support, with no permanent address and no stable job. With hope in his heart, in the August of 1849, at the age of 31, Karl then sought refuge in London.

Material Misery

Karl arrived in London on August 26th, 1849, and was soon joined by his family on September 17. It was here, Karl began the founding of the headquarters of The Communist League. He also got involved with the socialist German Worker’s Educational Society which was closely associated with The Communist League. He began to funnel his thoughts to revolutionary activities and understanding the political economy and capitalism.

Poverty began to creep into the Karl household and during these trying times, Jenny gave birth to their fourth child Heinrich Guido, on November 5th, 1849, soon after which Engels arrived in London. By the year 1850, Karl got deeply involved in the study of political economics. As Karl progressively achieved intellectual success, the domestic scene began to deteriorate with time. With the bare minimum family income, supporting a family of six became difficult. Looking after young children took its toll on Jenny. With the growing domestic troubles, Jenny’s health began to deteriorate. Karl’s daughters also suffered illness and catering to the illness required money, which they could not afford. To make ends meet, Jenny had to resort to selling the family’s valuables and furniture. The constant threat from moneylenders and landlords left the family pain stricken.

The family had a tough time, arranging for alternate lodging, leaving them to lead their lives in poverty, hunger, pain and distress. Through the difficult times, Karl provided his all to work and worked incessantly with Engels. By May, Karl moved to Soho in London which was a very poverty stricken area. The Karl family rented two small rooms and lived in utmost poverty and filth.

However, Karl and Engels together, kept working tirelessly on the political and societal endeavours they had undertaken. They worked on the many issues to be published in The Neue Rheinische Zeitung and Karl concentrated on his political study of the economy. His financial condition however did not improve greatly and Engels, in an attempt to ease the situation, would lend him money. The expenditure in Karl’s household was always a question of worry as Karl always suffered from the lack of it. He was born in a bourgeoisie family and Jenny too had an aristocratic lineage. Even in financial distressed times, the family stuck to the bourgeoisie lifestyle. The Karl family always had the luxury of a maid. With time, many questions arose about Karl’s lifestyle. Also, Karl always intended for his daughters to marry in well to do families and allowed them every luxury like holidays, visiting relatives, expensive gifts, clothing and attending social gatherings even when he could not afford it. The money situation in the Karl household remained tense, to the extent that Karl would pawn his clothes to collect money for his tobacco. Karl’s mother Henrietta said, “If Karl, instead of writing a lot about capital, had made a lot of it... it would have been much better.”

Through the first few years that Karl lived in London, Engels was a pillar of support, both intellectually as well as financially. Engels derived most of the income from the family inheritance which he gave to Karl. In order to further help him, Engels then joined the firm, ‘Ermen & Engels’ in Manchester, England. The poverty of the family was static and it was one of the reasons why Karl saw the death of his son, Heinrich Guido, who succumbed to illness on November 19th, 1850, only a year after he was born.

Putting his troubles behind, Karl worked on his book, ‘The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon’ from December. The work emphasized on the French Revolution of 1848, historical materialism and the class struggle. Karl was now more prominently transforming from an idealistic Hegelian into the skillful and mature Karl who strongly knew what his political views and concepts were. He heard the joyous cries of his fifth child, a daughter named Franziska on 28th March, 1851. However, grief and troubles never left the side of Karl’s family. Recovering from the horror of losing Heinrich Guido, Karl was plunged into sorrow again when he lost his nearly a year old daughter Franziska on 14th April, 1852. The meager and poverty stricken lifestyle added to the illness she was suffering as a victim of cholera, due to which she could not survive long. The financial crisis were so grave that Jenny could not even afford a coffin for the little girl and had to scramble around for money.

During this time, in the March of 1854, Karl who was now 35, began to briefly write as a correspondent for the New York Tribune. He wrote about national liberation, international affairs and economies of the capitalist states. By 16th January, 1855, Karl’s daughter Eleanor was born and the same year, tragedy struck again when Karl lost his favourite son, Edgar. An epidemic of cholera was spreading in the region and it began to devour many lives. Edgar fell into the clutches of the illness and succumbed to it on April 6, 1855.

Those were the most dreadful years of Karl’s life. They not only challenged him physically and financially, but demanded and stole a lot of his emotional stability as well. Their poverty was not something that was hidden. The house was situated in the cheapest neighbourhood and had not much to be called as furniture. Every item was torn, tattered and dirty and the house was messed up with the children’s toys, manuscripts, books and newspapers scattered all over the place. The atmosphere at home was not favourable and this had led to their son Edgar falling ill. The house suffered tragedy after tragedy.

Karl was writing for the New York Tribune newspaper, which by the year of 1856 was accepting fewer and fewer of his articles. Despite the many tribulations, Karl then began learning and understanding the Political Economies and Capitalism. He spent endless hours accumulating information and data on wage labour, landed property and capital and in 1859, published his economic work titled ‘Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy’. He then worked on the Theory of Surplus Value, which was concerned with examining the ideas of the British, French and German economic theories on the creation of wealth. Karl went on to explain, how being unable to solve basic contradictions in the labour theories caused their classical school of economy to eventually break up. The many books and enormous research took a lot of Karl’s time, and he spent the 1860’s studying and analyzing them.

Karl loved his family and spending time with his daughters. In the 1860’s, he and his daughters would love to play the Victorian parlor game, ‘Confessions’, during which once he was asked, what was his idea of Happiness? He replied, “To Fight,” and then when he was asked what was his idea of Misery? He replied, “Submission.” His words during a fun game of ‘Confessions’ displayed his courage to fight and his approach to never give up.

By January 1860, the New York Tribune discontinued their association with Karl and therefore, he began writing for many other newspapers. Illness came knocking in the November of 1861, when Jenny was struck with small pox. While she was still recovering, Karl found himself ailing, and in the November of 1863, Karl suffered another loss when his affectionate and love smothering mother expired in Trier.

Karl gathered himself together and in early 1866 he began work on the final version of the first volume of ‘Das Kapital’. It drained the energy and time out of Karl’s life. On August 16, 1867, Karl was 49 when Das Kapital was finally completed. In Das Kapital, he emphasized on the labour theory of value, the concept of surplus value and the exploitation of the working class. Das Kapital was said to be his most riveting work until then, which analyzed the capitalist form and process of production. There were many other minor achievements, but his most famous and influential work was Das Kapital. After the completion of the first volume, Karl continued his work on the second and third volumes. On the 2nd April of 1868, Karl saw domestic bliss with the marriage of his second daughter Laura to a French socialist Paul Lafargue. During this time, his eldest daughter Jenny began to write along with her father and supported him whole heartedly. Along with him, she wrote many articles for the Le Marseillaise, a Parisian newspaper in 1870. The 1870’s brought more ill health to Karl. He became incapable of performing and working like he would before. In the September of 1870, Engels moved from Manchester to London and began working closely with Karl.

On 10th October, 1872, Karl’s eldest daughter Jenny married the French socialist, Charles Longuet. During this time, the authorities however, began to garner suspicions against Karl. He was called, “the Chief of the Red International” and the police kept a close eye on him. Karl applied for British citizenship, but was denied it in 1874. He faced rejection, tragedy and illness from all ends. However, Karl never deterred from his path and engrossed himself in completing the second and third volumes of Das Capital. It was now that he had started gaining recognition and success. Das Kapital was now to attain the glory it was destined for, but Karl’s health hampered him from enjoying the rich harvest of his works. His health deteriorated way too much and he suffered from mental depression and insomnia. His wife too fell ill and suffered from incurable cancer and passed away on 2nd December, 1881, in London. Karl then travelled to Algeria, the south of France and Switzerland and also visited his daughter Jenny. His health began to further deteriorate, but Karl still kept working. Tragedy did not stop here. On January 11, 1883, Karl’s eldest daughter Jenny died of cancer. This was the final blow. After her death, Karl barely interacted or spoke with anyone. He had endured tragedy after tragedy and he finally ceased to think on March 14,1883 perishing to Lung Abscess at the age of 64 in London. He spent his entire life in misery, tragedy and searching for a place he could call home, but he never got that opportunity and died a stateless person.

The Thinker of the Millennium

Karl’s funeral service was held in London on 17th March, 1883, and he was then buried at the High Gate Cemetery. The service was attended by approximately 11 people who included Karl’s daughter Eleanor and his sons-in-law, Charles Longuet and Paul Lafargue. His grave was then adorned by a bust of him and his tombstone bore the final sentence and the most compelling words of The Communist Manifesto: “Working men of all countries, UNITE!”

Karl kept working incessantly till his last breath. ‘Das Kapital’ was one of his most profound works but he lived to see only the first volume being published. His lifelong friend and colleague, Friedrich Engels then edited and published the second volume in 1885 and third volume in 1894.

History saw many great thinkers and due to his works, Karl reserved a position for himself amongst the cream of that list. His take on society and economics became the viewpoint of millions. Over the years, many have revered his theories, and his works have become the basis of political change. The BBC polls tagged Karl Marx as the “Thinker of the Millennium” and the “Greatest Philosopher.” His theories affected science, economics, politics, culture and history.

They were later dubbed as Marxism and every individual concocted an interpretation of the theories. It became the foundation of political transformation all over the world in the form of Maoism (The Marxist interpretation the Chinese leader, Mao Zedong). It formed the basis and the guiding ideology of the Communist Party of China, Leninism ( The interpretation of Russian revolutionary, Vladimir Lenin which comprised of many economic theories and practical application developing the agrarian Russian Empire), Stalinism ( The interpretation of Joseph Stalin implemented in the Soviet Union) and Guevarism ( The interpretation of revolutionary leader Ernesto “Che” Guevara, comprising of Marxist ideas combined with guerrilla warfare for the upliftment of the proletariat).

Karl’s message of a classless society has since then been a ray of hope for millions. Many individuals around the world would agree with Austrian economist Joseph A. Schumpeter in calling Marxism a religion and Karl its prophet. He brought forward major change in the theory of communism and socialism and provided a better understanding of the socio-economic problems of the world.

The man that changed the world suffered a scandalous and poverty stricken life. The world came to know his name, but he could not call even a single country his home and died a stateless person. His critics thrashed his way of thinking to the extent of calling him ‘an agent of Satan’, but on the other hand, his followers have seated him on the high pedestal of their lives. Controversy and tragedy never left his side. Karl was accused of an affair and fathering a child out of wedlock with his maid, Helene Demuth. His daughters, Eleanor and Laura outlived him but he was to bear the heavy burden of seeing the rest of his children and his wife perish before him. The amount of tragedies never diminished in the Karl household and his life was an example of pain and poverty.

However, Karl’s legacy has endured through time, not through his progeny but through his works. The three major works of Karl Marx were: The Communist Manifesto which he co-authored with Friedrich Engels in 1848; A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy in 1859 and the three volumes of Das Kapital which were published in 1867, 1885 and 1894 respectively.

It was Karl who said that capitalist development prevents human beings from reaching their full potential as self determining beings. He went on to say that only when private property is abolished and there is the overthrow of capitalists along with the establishment of communal ownership of the means of production by the initial dictatorship of the proletariat can economic equality and justice be acquired. Karl’s work on economics and political ideas is the central driving force of communism and socialism. His contribution to the understanding of our society is enormous and he is greatly admired by academics for the same.

Karl Marx studied to be a philosopher, drifted towards politics and economics and was then tagged as a revolutionary communist. Many versions and interpretations of his theories surfaced and even more analyses were raised about how he led his life. The world is divided in two parts; one part which considers Karl to be a prophet and the other who think him to be Satanic. His biographer Francis Wheen, in his book, ‘Karl Marx- A Life’ mentions, “Not since Jesus Christ has an obscure pauper inspired such global devotion- or been so calamitously misinterpreted.”

Next Biography