Introduction

“I am the wisest man alive, for I know one thing. And that is, I know nothing,” Socrates would say often. These were also the words he used to defend himself when tried in court on allegations of inciting youngsters to rebel against the Athenian state. Paradoxical as they sound, this utterance of Socrates aptly reflects the Hellenic thinker’s entire life: While some considered him a genius born before his time, others believed he was a madman whose rants and ramblings on the streets and public places of Athens merited only a mere hearty laugh.

Had those who mocked Socrates been alive today, they would have definitely eaten their words- as the old proverb runs- knowing they had blundered and lost an invaluable opportunity to learn from a compatriot whose teachings have wide implications even some 2500 years after his execution. “The unexamined life is not worth living,” Socrates said. Here we will study the life of Socrates who remains a much debated entity to date, outliving his own ‘gadfly’ method of debate which poses difficult questions to respondents, either to confuse them, elicit an anticipated answer or merely, as an irritant.

Socrates is now acclaimed as a pioneer of Western psychology since he opened moral, ethical, political issues related with virtue and justice through his thoughts.

Birth of Socrates

Details about the life of Socrates can be found in extant texts, especially the ‘Dialogues’ authored by his students, Plato and Xenophon, dramas written by the ancient Hellenic comedy playwright Aristophanes and records of the renowned Greek thinker, Aristotle. These books indicate, Socrates was born in Athens in 469BC. His father was an accomplished stone mason named Sophroniscus while his mother was a midwife called Phaenarete.

Education

Conforming to prevalent traditions, young Socrates studied at a regular Athenian school learning subjects such as religion, culture, Athenian history and mathematics.

At home, he helped his father Sophronicus to carve statues of Greek mythical deities and rulers. Sophroniciscus’ craftsmanship was widely acclaimed, and he received the patronage of rich and powerful nobles and hence was able to gain access to the ‘Inner Circle’ of a revered statesman and prolific orator, Pericles.

The Turning Point

Socrates was an average student since he never liked conventional subjects. Once his father, Sophroniscus took Socrates to a debate hosted by Pericles at the Public Library of Athens. Though a silent spectator, the debate, in which several nobles and aristocrats participated, left a lasting impression on the young mind of Socrates. It was here he found his true calling: Introspection, thought and discussions. This event was to become the turning point of Socrates life, though at the time, he was too young to be permitted to debate at such a prestigious place filled with nobles.

Socrates was astounded by the voluminous knowledge that aristocrats, religious leaders and rulers claimed to have, during this debate hosted by Athenian noble, Pericles. But, he was not impressed. He felt all participants at the debate lacked explicit knowledge of the issues on which they spoke. The woes of Athens and its citizens were ample proof that nobles, religious men and rulers had thrown ethics to the winds, hence their talk was hollow. But propriety did not permit Socrates to question these men.

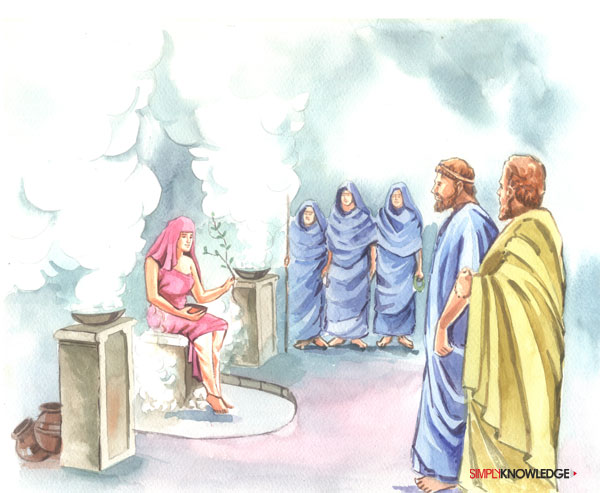

Socrates and Pythina, the High Priestess of Delphi

After the debate, Socrates mocked every person who claimed to be “wise.” He would annoy these people by asking them questions to an extent, they would fumble and hence, never reply. An exultant Socrates dramatized his new finding by announcing to all and sundry that he was the wisest man ever born, since he understood the extent of his ignorance. This caused Socrates to be mocked and reviled by people, who believed he was mentally ill and hence, gone berserk.

“I am the wisest because I know nothing,” he told Chaerophon, a close friend. The two argued on this statement because the latter did not know what Socrates meant. They decided to refer the issue to Pythina, the high priestess or Oracle of Delphi, selecting her as a neutral judge since she was revered and perceived as “wise”. Chaerophon asked Pythina if Socrates was the wisest man in Athens since he claimed he had no wisdom. Pythina replied affirmative, meaning Socrates was indeed wise, because he acknowledged the extent of his ignorance.

Puzzled at the response, Socrates believed he was wise since he did not make any superfluous claim to wisdom and knowledge. By doing so, he did not deny that knowledge was available. Socrates came to believe that true knowledge can only be attained by testing every claim of wisdom made by a person.

Hence, Socrates began questioning the wisdom of whoever he met, with a view to gain knowledge himself, but ended up proving through his method of questioning and cross-questioning, called ‘gadlfy’, that men who claimed to be wise, were in actuality, wrong. Socrates thus inadvertently fathered what is today called the ‘Socratic Method.’

Pythina, is hence credited as being the first teacher of Socrates who set him on path to newer discoveries in methods of gaining knowledge. He began questioning everyone he came across to find if he would stumble upon a genuinely “wise” man.

Socrates the Teenager

The meeting with Pythina, left a lasting impression on Socrates, who began pestering his teachers with questions they often could not answer. As a result, Socrates concluded that most men do not know themselves or the subjects they teach, leading him to believe that regular studies are banal. He was however interested in religion and would read manuscripts and other available literature on Greek deities and their rituals. He thus took it upon himself to form a new school of thought that would help people understand themselves first before they embarked on any ambitious missions to gain knowledge about other subjects. “The greatest way to live with honour in this world is to be what we pretend to be,” he rebuked a teacher, who could not provide proper answers to Socrates’ many questions. He attempted to emphasize that a good teacher must possess knowledge in its truest sense. Such knowledge will enable a teacher to impart proper knowledge to students and respond to all questions properly. Teachers who are unable to do so, Socrates said, face the imminent risk of losing respect from their students, who would perceive them as teachers without proper understanding or knowledge of a subject.

Initial setbacks

Socrates ambitions of becoming a young thinker and orator were scotched by prevailing Athenian laws on conscription: The republic-state was at frequent wars with the Spartans and other empires and it was compulsory for teenagers to serve the military as their divine, national duty.

Upon attaining the age of 16, Socrates was conscripted into the Athenian army and underwent extensive training in combat, weaponry, charioting, war stratagem and stealth. The ‘Dialogues’ of Plato state, Socrates possessed a rugged body, a broad forehead and agile feet, which rendered him fit for military service.

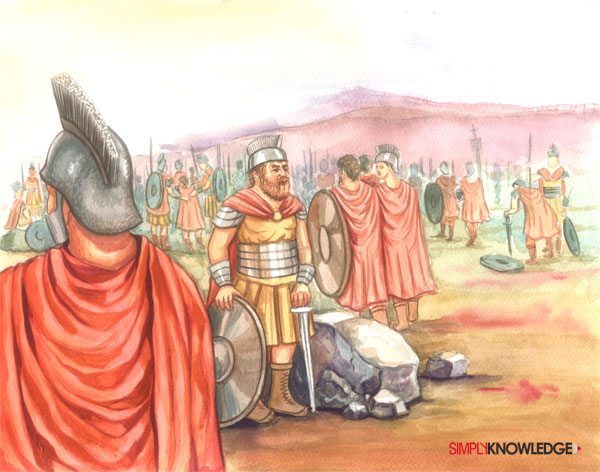

Socrates at War

The teenaged Socrates became a muscular, well built albeit grotesque ‘hop foot’ soldier thanks to rigorous military training, and saw action in three wars- Potidaea, Amphipolis, Delium.

Plato credits Socrates as a valiant soldier. Xenophon in his work ‘The Symposium’, quotes Alcibiades as stating that Socrates twice gave him a “new life” by saving him from imminent capture, torture and death at the hands of invading Spartans during the took part in the Battle of Delium in 432BC. Socrates rescued Alcibiades for the second time during the Battle of Delium in 424BC. The Hellenic general also credits Socrates for his chivalry in ‘Laches’, another Socratic dialogue by Plato.

Socrates began his teachings during his days as a soldier. He would indulge in small talk with comrades and eventually, speak out his own thoughts. Socrates motivated other soldiers by extolling virtues of patriotism and qualities of an indefatigable combatant by saying: “He is a man of courage who does not run away, but remains at his post and fights against the enemy.”

Combat fatigue

Valour, bravery and moral support for other soldiers earned respect for Socrates. But as the futility of armed conflict and the insurmountable loss of life and property due to frequent wars dawned upon him, Socrates became cynical about the entire polity and governance. Having lost respect for rulers who put their populace in the line of fire, he developed a strong disdain for the nobles. While performing his duty for the state, which he held divine, he also became an eccentric of sorts.

He lost interest in material and pecuniary gains after witnessing how armies plunder and pillage the innocent population of a conquered land for personal gains. “One who is injured ought not to return the injury, for on no account can it be right to do an injustice; and it is not right to return an injury, or to do evil to any man, however much we have suffered from him,” he once said to his commander and comrades to express that revenge of any sort against defeated enemy was tantamount to sacrilege. Victorious armies usually castrated enemy soldiers and dismembered other males alive while raping hapless women as psychological warfare, to assert superiority and impending dominance.

Proximity to Alcibiades and skills as a valiant warrior saved Socrates from a court martial and imminent execution for mutiny for such a statement that could have demoralized other troops, while deployed on forward positions during these wars. But the apparent disinterest by other soldiers only depressed Socrates further.

Intimacy

Socrates was nearly 30 years old when he returned to Athens. His later life was marked with a series of affairs. Notable among these are the ones with his benefactor, Alcibiades who had become his admirer before the end of the war and during peace, and in time the two forged a strong friendship. This closeness to Alcibiades once again brought Socrates some degree of immunity against prosecution for denigrating existing laws and systems of the Athenian state. Plato’s records claim, Alcibiades and Socrates were “lovers”- which indicates the extent of their friendship. During that era however, same gender relations between nobles and their followers or teachers and pupils were said to be common.

They state, Socrates had “deep affection,” or an affair with Diotima, from Mantinea in the Athenian empire, who claimed to be a priestess bestowed with magical powers and Aspasia, a concubine of Pericles, with whom he may have had an intimate affair, since Socrates was close to him.

Diotima, claimed Socrates, tutored him about Eros, the Greek god of love and carnal desires. Her charm had Socrates captivated for several years, during which she taught him “Eros’ worship,” or the art of fulfilling carnal desires and pleasures. “Beauty is a short-lived tyranny,” Socrates told Diotima, since he was literally under her spell. “Beauty is the bait which with delight allures man to enlarge his kind,” he said to the priestess. Diotema, it is believed, was his first wife. But as a priestess, she was not allowed to procreate.

Aspasia was quick witted and highly accomplished academically. She taught the art of rhetoric to Socrates, as revenge against Pericles, who never acknowledged her skills. Socrates was overwhelmed by Aspasia’s knowledge and praised her saying: “Once made equal to man, woman becomes his superior.” Intimate affairs with Aspasia are not recorded but for some reason, their relationship collapsed. “From the deepest desires often come the deadliest hate,” he said, when the two parted ways. Despite, Socrates mentions Aspasia among one of the tree women he adored, which included his mother, Phaenarette and Diotema.

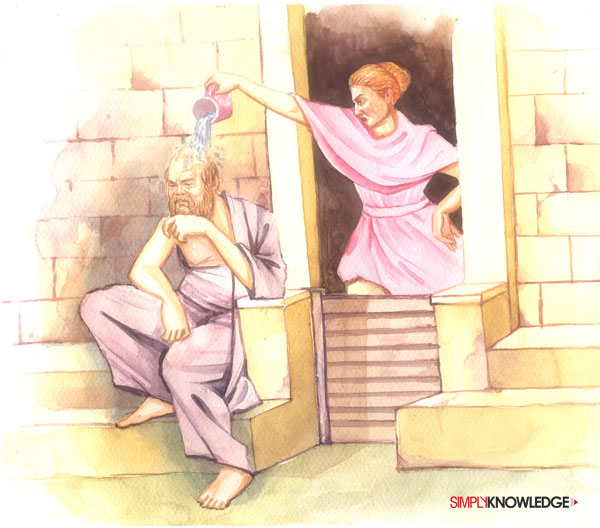

Marriage

Plato’s work ‘Phaedo’ and Xenophon’s ‘Memorabilia’ which document various facets of their master’s life record: Socrates married Xanthippe, an Athenian woman, believed to be much younger than Socrates and with no claim to any aristocratic ancestry. The two describe Xanthippe as a sincere, devoted wife who was faithful to her eccentric husband till the day of his execution. Xanthippe and Socrates often argued on family matters, leading some lesser known chroniclers to depict her as a proverbial shrew, who often quarrelled with her husband.

The bone of contention between Socrates and Xanthippe was the self-styled teacher’s utter disregard for the family and its needs. The couple had three sons, Lamprocles, Sophroniscus, and Menexenu.

Socrates and his strange behaviour caused immense embarrassment to Xanthippe and their children as they grew, since some people termed their father as a madman for ranting and rambling his thoughts and beliefs in public and sacred places. This was further aggravated by Socrates’ lack of interest in family matters and above all, his sheer belief that teaching is a divine profession and hence, no fees are to be charged from students, causing immense pecuniary hardships to Xanthippe and their kids, who eked an existence from charity by some vague supporters and critiques of Socrates.

That Socrates had utter disregard for marriage is aptly reflected when he told a compatriot who sought his views on matrimony: “My advice to you is get married: if you find a good wife you'll be happy; if not, you'll become a philosopher.” Despite such disdain for marital relationships, there are no records indicating Socrates ever had a troubled marriage because of Xanthippe. Indeed, Socrates had caused financial woes to his family and was unwilling to fulfil his paternal duties towards their three sons. This was one of the main reasons that several Athenians dismissed Socratic teachings as those of a mentally deranged person, shell-shocked from the war. He once said to his young followers: “As to marriage or celibacy, let a man take which course he will, he will be sure to repent.”

Stark mad or an unparalleled genius?

Armed with his worldly knowledge on various subjects, having skilled the use of rhetoric and believing he was divinely ordained to teach, Socrates embarked to fulfil his ambition of becoming a teacher. Eccentric as he was, Socrates believed, he possessed no tangible knowledge about the real sense of life and all worldly teachings were frivolous in his belief- as told to him by Pythina, the Oracle of Delphi, while he was a teenager.

Thus he would tell people: “True wisdom comes to each of us when we realize how little we understand about life, ourselves, and the world around us.” He would accost any person without reason and begin bawling his thoughts at them, hoping the bewildered stranger would comprehend his teachings. Socrates believed that reasoning, thinking and questioning were some of the sound methods to gain true knowledge. He thus held meetings in parks, markets and public places, which were a free-for-all event.

Those who understood the essence of Socrates thought’s, regarded him as a genius and followed his teachings further while others dismissed him as an incorrigible psychotic, believing his meetings were a place for amusement.

Verbal rants denigrating contemporary “intellectuals” and rulers

He insulted poets, who were considered among the intellectuals of the era through public statements such as: “I decided that it was not wisdom that enabled poets to write their poetry, but a kind of instinct or inspiration, such as you find in seers and prophets who deliver all their sublime messages without knowing in the least what they mean.” While some considered him a genius born in the wrong place at the wrong time, others suspected he was a lunatic, due to his unkempt appearances, plight of his family and uncouth condemnation of everything held sacred by ancient Athenians.

The playwright Aristophanes depicts Socrates as a comedy character in most of his plays, because of his behaviour that contradicted all accepted forms of behaviour and respect. He launched wanton attacks on Athenian rulers by openly scorning their ambitions with words such as: “Let him that would move the world first move himself.”

Socrates never consumed alcohol and hence his eccentricity could possibly be explained as a vent to his subconscious disgust over the wars and its aftermath. “A system of morality which is based on relative emotional values is a mere illusion, a thoroughly vulgar conception which has nothing sound in it and nothing true.”

Despite Socrates recognizing his own ignorance, he held some unshakeable beliefs and he investigated many subjects such as piety and ethics. He professed that any person of good moral character can never be harmed because despite misfortunes, his inherent virtues will not degenerate. Socrates laid great emphasis on ethics. “All men's souls are immortal, but the souls of the righteous are immortal and divine,” he told his followers and critics.

Socrates publicly castigated the rich and famous saying: “If a man is proud of his wealth, he should not be praised until it is known how he employs it.”

He chided people for striving to earn money for their living by saying: “Worthless people live only to eat and drink; people of worth eat and drink only to live.” Socrates attracted the wrath of some rulers and paradoxically, admiration of a few others in power. Aristocrats who admired Socrates, invited him to their palaces and banquets. He would go dressed in his shabby attire and spare no effort to unleash stinging remarks upon the rulers and their citizens.

He never partook of the royal feasts but was content with a piece of coarse bread, cheese, condiments and vegetables, eating them at will with hands rather than follow etiquette.

Several nobles attempted silencing Socrates since they believed he was a great person who had made greater enemies. A few aristocrats offered him jobs on lucrative terms. But these appeasements were declined curtly. Socrates believed he was a teacher and hence, had no right to profit from his teachings or thoughts. “He is richest who is content with the least, for contentment is the wealth of nature,” he told every nobleman who tried to hire his services as a bureaucrat.

Socrates and Plato

It was during one of these royal banquets that Socrates and Plato first met. The young Plato was awed by Socrates and his esoteric doctrines and was also disgruntled at the governance of the Athenian empire and its vassal states. Plato was worried about the utter lack of concern for common citizens by the ruling elite and the frequent wars against Spartans and their allies. For some reason, Plato believed the Athenian empire was in its death throes and its downfall, imminent.

Plato and Socrates struck a conversation, which left an indelible mark on the elder thinker and teacher. He encouraged Plato to attend his meetings at marketplaces, gardens and other public venues. Within a few years, Plato was a confirmed, ardent pupil of Socrates. Several followers of Socrates believed, and rightly so, that young Plato would succeed their master.

“Be slow to fall into friendship; but when you do, be steadfast and loyal to your friends,” Socrates told Plato during a personal talk with his successor. And Plato held on to his master’s words, till the bitter, dramatic end.

Wrath of the royals

Eccentric as he was, Socrates had scant respect for the Athenian government. As years progressed, his rants and ramblings against the empire assumed exponential and alarming dimensions. Socrates would often praise the Spartans for their style of rule and respect for citizens. Consequently, several young men who were dissatisfied with the Athenians, began attending Socrates’ speeches in large numbers. This attracted angst from the rulers, who continued to dismiss him as a lunatic and hence, of no consequence: They faced a much larger issue of frequent assault on the empire’s territories by the Spartans and the Persians. Socrates, true to his nature, had not allowed for any political upheavals in Athens since he believed the local populace were too complacent to rebel against any authority.

Little did Socrates realize he had crossed every permissible limit of social and political propriety and facing consequences for his reckless actions was inevitable. The master also failed to foresee that Athens would soon fall into enemy hands.

The defection of Alcibiades and fall of Athens

The renowned Spartan commander, Lysander, once again routed the Athenians in 405BC, forcing Alcibiades defection. Alcibiades and his mistresses hid in enemy territory. This effectively ended any immunity from prosecution by law that Socrates enjoyed for saving Alcibiades’ life twice. These battles were collectively termed the Peloponnesian War and included several other conflicts of varying degrees between Athens and Sparta.

The end of the Peloponnesian War in 404BC saw Athens fall in Spartan hands. A pro-Sparta regime that consisted of 30 Greek politicians who owned allegiance to Sparta took over governance of the Athens.

Apparently unshaken by these events, Socrates continued with his capers. The political discontent by the 30 Greek politicians who had unleashed a despotic regime, caused more youth to follow Socrates. As his followers grew in numbers, so did the attention from the Athenian rulers, who were termed the ‘Thirty Tyrants’ for their horrible crimes against the population.

Precursors to Socrates’ trial

In spite of the general perception about the Thirty Tyrants as despotic rulers, their execution of Athenian elite and banishing to exile prominent personalities of the empire combined with their pro-Spartan ideology, Socrates continued to reside in Athens. Several Athenians viewed this as his subtle support for Sparta and the bloodthirsty rulers.

Plato, the most gifted follower of Socrates, was of noble ancestry. Critias, one of the Thirty Tyrants was Plato’s uncle, by virtue of being his mother’s cousin. Critias was closely associated with Socrates: a fact that did not appeal to patriotic Athenians who despised Critias for his persecution of innocent citizens.

Perictione-I, the mother of Plato would also visit Socrates along with her son and discuss issues related to knowledge, wisdom, righteousness and piety. She was considered an intellectual in her right, since she was highly educated and despite her royal ancestry, was simple. Plato mentions her as teaching some of her thoughts to Socrates, whenever the duo met.

Socrates had valiantly fought against the Spartans but did not flee the city along with others, fearing torture at the hands of the Thirty Tyrants. This led people to suspect, he indirectly supported their tyranny. The overall behaviour of Socrates during their rule, which ended after just over a year, indicated that he was sympathetic to the Thirty Tyrants and hence, had betrayed his compatriots. He was generally viewed as a traitor who had held deep grouse against Athenian rulers.

The betrayal of Athens by his benefactor, Alcibiades to Sparta, also contributed towards a general hatred against Socrates.

Socrates also remained indifferent to the arrival of General Thrasybulus and his army of Athenians who attacked Athens and overthrew the Thirty Tyrants, restoring a rule of law and justice. Instead, he said publicly: “I only wish that ordinary people had an unlimited capacity for doing harm; then they might have an unlimited power for doing good.” Socrates wanted to convey that Athenian soldiers and General Thrasybulus should now help in rebuilding Athens and restoring it to its past glory, which would benefit the empire’s citizens. However, it was wrongly construed as a criticism of the general and his patriotic army.

Socrates spared no effort to criticize Athenians and draw them into discussion. He held the Athenians solely responsible for the loss of their city to Sparta, blaming them for improperly educating the youth.

Charges against Socrates

By 399BC, Socrates was considered as an enemy of Athens by several citizens. Though he was respected for his teachings in some circles, his overall behaviour during the rule of the Thirty Tyrants and later, came under the state’s scanner.

Scholars opined the trial of Socrates was as paradoxical as the accused himself: Athens was known for freedom of speech and expression, recognized as a right of its citizens. However, Socrates, who claimed he was knowledgeable since he recognized he lacked knowledge, was on trial for exercising this very right in his quest for wisdom.

Socrates, in his ramblings, would inspire youth to embark on missions to acquire true wisdom which was based on spiritual values such as love and piety- the very basis of the Athenian state’s greatness. Yet, he was accused of inciting youth to rebel against the Athenian empire.

The charges of sedition by corrupting youth to question traditional concepts of wisdom, to ensure that rulers were truly wise and possessed knowledge, were levelled against Socrates by three accusers- Meletus, Anytus and Lycon.

Meletus, a poet, bore a personal grouse against Socrates’ for frequent insults of poets who wrote flattering odes, without comprehending the meaning of what they penned. He was the youngest among the tree accusers and is suspected to have acted on behalf of other prominent poets who wanted to settle scores with Socrates while maintaining their own anonymity. Socrates had accused poets and orators of writing odes that focused on “useless flattery” instead of wisdom, piety and human values, which were fit for reading by slaves who pandered to their masters.

Anytus was powerful politician and is believed to have instigated nobles, poets and priests, among others, to prosecute Socrates. Though Anytus hailed from a socially lower strata of the Athenian society, his achievements during the Peloponnesian war with Sparta as a General and his contribution towards ousting the Thirty Tyrants from Athens, had made him popular among the public.

Lycon, an orator and politician sought vengeance on Socrates for personal reasons: He suspicious that his son Callias and Socrates were in an unhealthy relationship. Socrates had criticized Lycon and other orators of trying to curry favour with public using meaningless words that never materialized into action that would benefit Athenians.

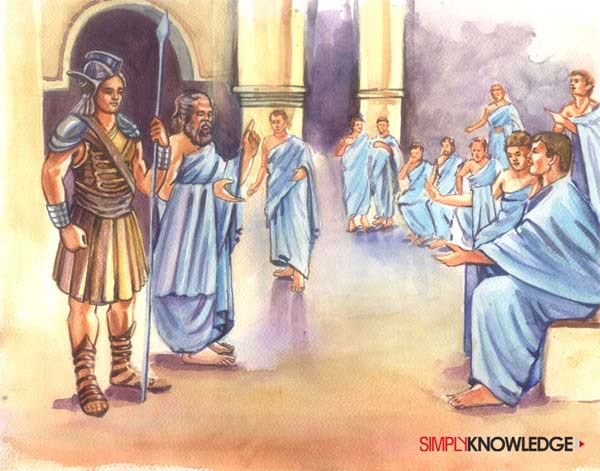

The Trial of Socrates

Under Athenian laws, any citizen could level charges of sedition in a court- a legal clause that accusers Meletus, Anytus and Lycon invoked to commence criminal proceedings against Socrates. The trial lasted for about 10 hours and was attended by a jury of some 500 men, believed to be commoners, selected by a draw of lots from nearly 5,000 applicants. Most of the jurists did not comprehend Athenian law of the ramifications of charges against Socrates, some scholars claim, adding, they merely opted as jurors out of curiosity, since they had heard about the thinker.

The trial commenced with a juror reading out charges against Socrates, which mainly focused around acts of sedition such as support for the Thirty Tyrants who had ruled Athens briefly, inciting youth to rebel against prevailing Athenian rules and seek reform, publicly denigrating values held sacred by Athenians and favouring the Spartans. Almost every student of Socrates worth mention, including Plato and Xenophon, were present at the trial.

Socrates heard these charges and replied them using his renowned ‘gadfly’ technique of responding with questions. “Proper conduct means to pay attention to needs of the younger generation that would ensure a better future for all. This is similar to tending a garden: if the gardener is experienced, he will witness great blossoms. Similarly, we have to care for the younger generation before attending to others, who are already opinionated,” said Socrates, in his defence against charges of corrupting the minds of youth.

He succeeded in proving that virtue was not inherent and were imbibed through training of the mind, the fallacy of prevailing Athenian concepts and a justification of his own teachings. “The human life is a maze of uncertainty. Therefore, do not rejoice when you are elated by any victory and nor be elated by a defeat. These are phases. Pray for all the people, since they need divine blessings and not for yourself therefore. For God knows what is good for you,” he said, answering charges about defiling Athenian religious rituals.

Throughout the trial, Socrates maintained he was a genius since he recognized his own ignorance. Socrates admitted to maintaining same gender relations with some of his young students, stating without him, these pupils would have gone astray- meaning, they would have broken the code of celibacy required in Athens.

The trial, which began in earnest, soon assumed all characteristics of high drama as Socrates and his accusers battled their wits. The three accusers, Meletus, Anytus and Lycon were no match for Socrates and his ‘gadfly’ and almost conceded defeat at the end of the trial, certain that the accuser had impressed the jury and to avoid imminent humiliation by the public for levelling frivolous charges.

Sentencing of Socrates

The amused jury was split over the verdict. They were also unsure whether to punish Socrates or acquit him. The absence of a judge at the trial, held at a public court in Agora in Athens, added to the confusion since there was nobody who knew the law and could direct the jurors who themselves were unaware of prevailing rules and the repercussions.

However, due to gravity of the charges, a guilty verdict was pronounced. Despite, Socrates was offered an opportunity to seek his own punishment. He could have gotten off by paying a fine- which his students would have eagerly contributed.

Socrates concluded his defence, saying: “I am simply persuading the young and old not to consider their status or wealth but focus on improving their soul through good deeds. Virtues do not originate from wealth. Instead, virtue generates treasures for every person and the state. I cherish these teachings, for which I stand accused of corrupting the youth. In this case, I fully accept the charges and asset that I have broken the laws.”

Eccentric as he was, Socrates, instead of choosing some rational punishment, told the jury that Athens and its citizens should recognize his contributions and reward him by providing free meals at the Prytaneum, a public dining hall in Athens for the rest of his life. The stupefied jury sentenced him to death, in principle, hoping some legal expert would be able to pass a proper judgement later, if Socrates appealed.

Socrates’ incarceration

But Socrates did not appeal. Instead, he chose to be incarcerated immediately and as per wishes, was jailed in a common cell at a fortress on the outskirts of Athens. And he asked for the death sentence to be enforced without any special considerations.

While imprisoned, Socrates utilized all available time to continue teaching his students and curious visitors who flocked the jail to glimpse at the person who had already become a legend. Socrates was sure of his death and hence, wished to preach everything he possibly could, during that period.

Plato, Xenophon and other eminent students visited Socrates almost daily. His wife Xanthippe and their sons Lamprocles,Sophroniscus,Menexenu would also visit Socrates in jail. The founder of Western thought spent about a month in prison, awaiting execution.

Rejection of amnesty and escape plans

The three accusers, Meletus, Anytus and Lycon, secretly appealed for Socrates’ life to be spared and he was offered amnesty, provided he paid a very nominal fine. Plato, who hailed from a wealthy aristocratic family and Xenophon as well as other students raised the cash. Socrates refused to budge and forbade them from paying the fine. “There are only two tragedies in life: One is leaving your ambitions unfulfilled and the other, achieving these goals,” Socrates told his students to convey, he did not fear death since his life was tragic: He had missed his goal and yet achieved it, through his works.

Plato and other followers also planned to bribe the jailors to allow Socrates to escape to a safe haven. But Socrates stood firm, insisting that he undergo the death sentence, since therein lay his nobility and respect for the local laws. He is said to have severely chastised his students for conjuring such plans.

Last day of Socrates

A month after his incarceration, the day of Socrates’ execution dawned and he was duly informed by a prison officer. Socrates told this officer and his guards; “Ordinary people seem not to realize that those who really apply themselves in the right way to philosophy are directly and of their own accord preparing themselves for dying and death.” Some accounts claim, the prison officer came alone to meet Socrates and pointed to a small, mysterious stone tablet in his room, beneath which lay a trapdoor leading to a tunnel that would enable escape. Socrates declined the offer and instead, said to the officer: “The end of life is to be like God, and the soul following God will be like Him.”

Through the day, several followers flocked to meet Socrates, including Xenophon, his wife Xanthippe and their three sons. Plato was sick and could not visit Socrates but instead, his mother, Perictione-I met Socrates and the two discussed theology and other perspectives of life and death.

An hour before the execution, a prison guard informed Socrates that he should prepare himself for death by saying farewell to his visitors, having a bath and dressing in new attire, ready for burial. Upon hearing this, Socrates left the cell, bathed and dressed, as instructed. Upon return, he requested Xanthippe and his sons as well as several others to leave, since he required time with his students.

The execution

Shortly after the departure of guests, the prison officer whom Socrates had sermonized arrived with a cup of Hemlock- a potent poison. The officer drew Socrates aside and whispered specific instructions on how to consume the fatal dose, in a manner that would ensure quick, painless death.

Socrates took the cup, pondered for a few seconds, looked at his disciples and swallowed the poison, handing over the empty goblet to the prison officer, who departed in great hurry, possibly because of his sympathies for the thinker either due to his greatness or advanced age.

The super genius or the eccentric madman, the valiant soldier who saved a general from imminent gory death or a traitor whose words spoke well about the enemy- Sparta, a truly divine man or a blasphemer, by whatever epithet Athenians described him, was living his last hour on Earth, possibly with deep resentments or utter contentment with his life. “It is not living that matters, but living rightly,” he had preached. And he was dying for the cause: Socrates had spurned offers to be released on bail or escape because he staunchly believed, as a law abiding citizen, he had not harmed the society or state.

That he was right in his life and would uphold the local law through his death. With these thoughts, Socrates went into painless yet spectacular death, witnessed by a handful of disciples, who chronicled it later.

The golden hour

Very few instances of people narrating the final moments of their lives exist. There are near-death experiences that are well documented, but examples of a dying person recording their physical and mental state during execution are extremely rare. One among such unique records is that of Socrates, as he entered his last minutes after consuming the fatal Hemlock.

Upon consuming the fatal dose, Socrates followed every instruction given by the prison officer. He paced in his cell, possibly an action aimed at expediting the onset of the toxin through increased blood circulation that results from a brisk walk.

Socrates stopped for a moment and addressed his students saying: “You will now hear from me a detailed account of how I die. The poison is already inside me and working. Hence, I have knowledge from which you may gain by observation but might never experience.”

His faithful student Xenophon began noting intricate details of death by Hemlock, as dictated by his master and from his own observations. As Xenophon was to later write, Socrates paced up and down the cell, trying to observe what was occurring to his body. The first experience he records is that of a sense of well-being or relaxation, either attributed to the poison or Socrates’ state of mind.

Shortly thereafter, Socrates said, he felt some tingling sensation in his toes and almost immediately, he told those present that he had lost control over his feet, as the poison begins taking effect. His pacing becomes slower as he loses sensation over the calves of his feet and a few minutes later, Socrates tells observers: “I have lost all sensation below my waist.”

At this juncture, records state, Socrates lies down on his bed and covered himself with the foulard, that went with him throughout the years, serving as both, a garment during the day and a blanket at night. He lies still but alive for some minutes and then admonished his student Apollodorus , for weeping. The ‘Phaedo’ penned by Plato narrates this account of the last minutes of his master. Socrates told Apollodorus: “Why are you crying? I sent away others because I did not wish to see any anguish during my last hour.”

A few minutes later, Socrates turned to another student Crito and said: “Crito, we owe a cock to Asclepius. Do pay it. Do not forget.” The chicken was to be sacrificed to Athenian deity, Asclepius and Socrates did not want to leave any debts- to humans or divine beings, unpaid. Crito assured his teacher that he would do the needful and asked if he required any other service.

Socrates went on to describe how the numbness triggered by the toxins had taken over his arms and breathing was becoming laborious. As Socrates began losing control of his lips and tongue, he uttered: “Death is either a dreamless sleep or a journey to another world. Both are to be accepted. Welcome death, come and purify my soul.”

Some records state, Socrates had a smirk on his face despite the pallor of death gradually taking over. His final slurred words were: “My tongue will not be able to speak anymore because it is already numb. The last thing I can tell you is, though I’m almost dead physically, something deep within says, even when my body is dead, I will remain alive.” Upon uttering these words, Socrates’ body stiffened. His students, Crito and Asclepius went over and found their master had passed away. They gently closed his eyelids and covered his mortal remains, which were laid to rest the next day.

These last words of Socrates indeed proved prophetic. Despite his death in 399BC, he remains one of the most widely debated and revered thinkers of all times, remembered as the pioneer of the Western school of thought and psychology, the epitome of ‘gadfly’ who invented a new, innovative method of learning by understanding one’s own ignorance, the use of pedagogic reasoning and many more achievements.

The extent of his contribution to the modern world can be understood from his various teachings.

Socratic Teachings

Socrates was the first psychologist to espouse the theory that humans lack knowledge of any type and nobody can lay claim to possessing true knowledge or wisdom. He epitomised this by frequently telling people: “I am the wisest because I know that I know nothing.”

Socrates tried to discover ways and means through which humans can live content and fulfilled life, regardless of material possessions. To attain this contentment, humans should first examine themselves to realize who we are, define what we believe in while introspecting into why these thoughts are dear to us and how we attain our final, purposeful objective of live. “To know yourself should be a major undertaking in your life. If a person is happy simply to exist, then what is the point of life,” he often questioned people.

Secondly, Socrates believed, relentless and incessant nurturing of one’s “inner self” or soul is imperative, since the nature of our inner being reflects on our physical existence and behaviour. The soul, according to Socrates, moulds a person’s character. A person’s intelligence is directly proportionate to how we nourish our souls, since our ethereal, innermost core forms the basis of our values, decisions and perceptions. Hence, humans who never cease to learn are nourishing their soul resulting in a life filled with knowledge and wisdom. Most humans never reach their full potential due to their inherent torpor towards learning, caused by pursuit of material and pecuniary gains. “Beware of the barrenness of a busy life,” Socrates warned.

He laid special emphasis on development of divine virtues among humans. Socrates said that a virtuous or pious person can never be harmed by any external force. He connotes that physical injury can occur to virtuous persons but they will remain largely immune to its pain and nor can any outer conditions disturb such persons’ souls. Hence, he concludes, no harm can ever befall such people, whom he enshrined through his saying: “All men's souls are immortal, but the souls of the righteous are immortal and divine.”

These teachings can be found in several religions which lay emphasis on divinity of the soul and state true wisdom is an exclusive domain of the Supreme Power.

The Socratic Method and Doctrine

An everlasting legacy of Socrates remains what is now termed the ‘Socratic Method and Doctrine’. Explained in simple terms, it means questioning a respondent on a particular subject. The response elicits another question from the quizzer. The process continues till the respondent runs out of answers, conceding their knowledge about that particular subject is superficial and was gained without proper scientific observation of objects animate and inanimate or natural and man-made phenomena. Often, the person probing the respondent through a series of answers in the form of questions will aim at gauging the extent of knowledge and its depth, as claimed.

Nowadays, the Socratic Method is adapted by psychologists, especially the Classic Adlerian Psycho Analysis and Psychotherapy, Cognitive and Reality therapies.

In these therapies, the psychologist assumes the role of Socrates or an interrogator and asks several open ended questions, which respondents answer according to their individual understanding of any issue or subject. A series of cross-questions posed by the interrogator or quizzer enables respondents to reflect on critical, intrinsic and extrinsic flaws in their own thoughts to identify any inconsistencies or aberrations and rectify them accordingly. The process, in turn, facilitates respondents to arrive at their own aphorisms, based on their newer chain of thought.

This adaptation of the Socratic Method or Socratic Doctrine is now increasingly used at educational institutions since an informal discussion, similar to those Socrates engaged in, helps students to question their teacher spontaneously, enabling them to learn any subject in an interesting manner while eliminating any erroneous conclusions they may have arrived at during formal teaching.

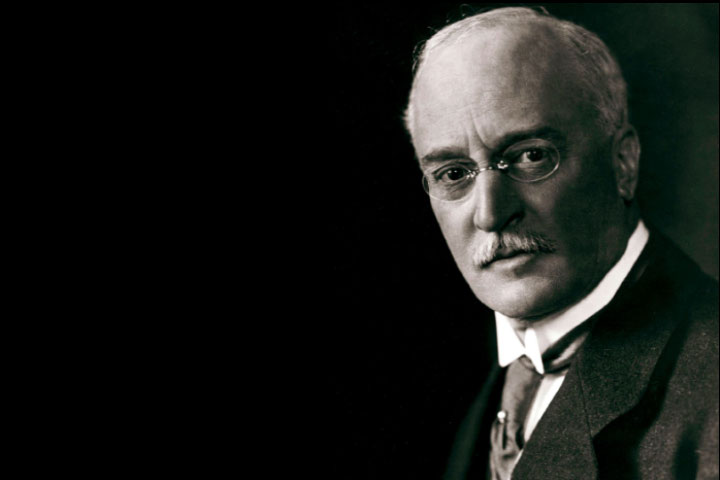

Socratic Method and Harkness Teaching

One such a modified method is called the ‘Harkness Teaching’, named after Edward Harkness, a philanthropist and oil baron from Cleveland, Ohio in the US. He is credited with making a large donation to the Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire, US to fund a new method of interactive teaching. This new system traces its origin to the Socratic Method, where teachers and students engage in a round-table, informal discussion that fortifies their learning helping both tutors and their pupils to rectify any mistakes in their understanding about a subject.

The new trials of Socrates

The importance of teachings of Socrates, his life and death as well as Athenian rules that prevailed during his time, evoke intense academic debate to date. Several trials of Socrates have been held over the last couple of decades to debate whether the ancient Greek teacher was indeed guilty or not.

The most recent such a retrial was held on May 25, 2012 at the Onassis Cultural Centre in Athens, a socio-cultural venue operated by the Alexander S. Onassis Foundation a Greek charity founded by the Onassis family of magnates. This was not a “mock trial”, a drama or re-enactment of the event that occurred about 2500 years ago.

Instead, it was a real trial aimed at determining whether Socrates was guilty or not of charges levelled against him and if he merited execution.

The court bench consisted of 10 prominent judges from six countries- UK, France, Switzerland, Germany, USA and of course, Greece. A Greek lawyer and a compatriot forensic expert represented ancient Athens while two eminent British attorneys were Socrates’ defence counsel.

Astounding Results

Court verdict: Five judges voted in favour of Socrates, stating he was innocent and five supported the City of Athens, affirming his guilt or the original sentence for which he was executed

Jury verdict: Of the 600 spectators who attended the retrial in Athens, 584 voted that Socrates was not guilty of the charges while only five jurists supported the charges of corrupting youth, supporting Sparta, the enemy of Athens and other charges that were levelled against Socrates by the City of Athens. Nine jurists abstained from voting.

Cyber Jury verdict: Over 2,000 jurists from across the world, including legal experts and students voted online by answering six questions posted on the Onassis Cultural Centre’s website. An overwhelming 75 percent of cyber jurists responded that Socrates deserved the death sentence if they were presented sufficient evidence that he had committed sedition against the State of Athens.

Guilty or innocent, madman or genius, patriot or traitor- it is certain that Socrates will forever remain a controversial figure for several decades and perhaps centuries to come. While some of his teachings are implanted in some form, adapted to suit modern day needs, others continue to be debated.

Next Biography