The birth of flame

It was the year 1837. Canada was in the throes of a severe political upheaval. Rebels fighting against the British crown were losing ground. Many were fleeing to the United States to escape prosecution by the government. One of these rebels was a man named Samuel Ogden Edison. Samuel, along with his wife Nancy Matthews Elliot and kids Marion, William Pitt and Harriet Ann, made for the bustling town of Milan, Ohio. Had Samuel not moved to the United States, the history of invention as we know it, would have been quite different.

On February 11, 1847, ten years after the family’s move to the United States, Samuel and Nancy welcomed their seventh and last child into the world and named him Thomas Alva Edison who was fondly called “Al” by his family. Al tended to be in poor health when little. His anxious parents worried over him as they had already lost three of their children Samuel, Charlile and Eliza born before Al. Nancy doted on her youngest child and not surprisingly, little Al quickly became the apple of his mother’s eyes. Curiously, Al did not begin to speak until he was almost four. His parents who were delighted when he uttered his first word soon despaired of his incessant chatter. He was a very curious child and had questions about everything that he encountered. He would shoot a barrage of questions at every adult that he met and woe betide them if they failed to answer his questions. He would fix them with his vivid blue grey eyes and ask yet another question “Why?”

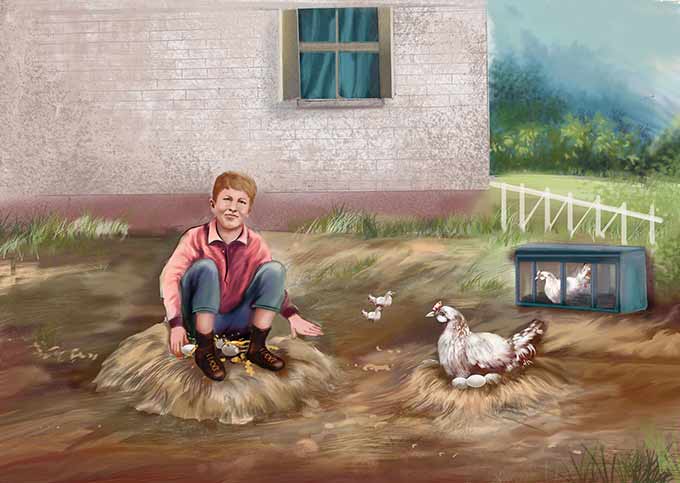

Al was a born experimenter. One of his first experiments was with the hen’s eggs. He had often noticed the mother hen sitting on the eggs to hatch the chickens. One day he thought of hatching some chickens himself; so he put several eggs in an empty nest and sat on them.

He was still patiently waiting for the chickens to hatch when his family saw him. His curiosity and thirst for knowledge often got him into trouble. Never far from mischief, he set fire to the family barn at the age of six.

The Fleeting School Boy

In 1854, Samuel moved the family to Port Huron, Michigan for better living prospects. Little Al, who was seven at that time, was enrolled into a formal school. Al was delighted as he could finally ask questions to his heart’s content and he proceeded to do just that, much to his teacher’s annoyance. His teacher was fed up with his never ending questions and seemingly self-centred behaviour. As the child had an unusually broad forehead and a larger than average head, the teacher termed him as ‘addled’ which meant confused or stupid.

When Nancy came to know about this, she was furious and promptly pulled him out of school.

Over the next two years, Al reportedly attended two more schools but none of his teachers could look on him as anything but a nuisance. Al’s attention would often wander in school. He also seemed to have been gifted with the knack of perpetual motion and seemed unable to sit still. Then there was his persistent chatter; Al liked to talk but not listen. All in all, he was never in any danger of becoming a teacher’s pet. His mother though thought differently and was firmly convinced that her child’s unusual behaviour and appearance reflected his inner genius. Edison remarked in later life, “My mother was the making of me. She was so true, so sure of me; and I felt I had something to live for, someone I must not disappoint.”

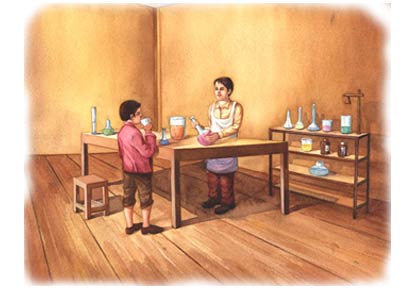

Nancy who was formerly a school teacher, decided to “home teach” her child. Al’s formal education lasted for just three months. His mother exposed him to books of a far higher level than anyone of his age, confident that Al had the ability to grasp complex concepts correctly. Under his mother’s guidance, the voracious reader devoured books on Science, Philosophy, English and History. Al loved Chemistry and Nancy who had the uncanny habit of reading her son’s mind, introduced him to R.G. Parker’s ‘School of Natural Philosophy’ which explained how to conduct chemistry experiments at home. Edison noted that this was “the first book in Science I read when a boy”

The young scientist

At the age of 11, when most boys think of nothing more than fun and games, Al had a very unboyish notion of setting up his very own laboratory. He started one in the basement of their house. His rather worldly father did not approve of such wholesale devotion to Science and so the father- son duo struck a deal: Samuel would pay Al ten cents for every novel or history book that he read.

Al readily agreed to his side of the bargain. The shrewd boy would read the books, collect the money and spend it all on buying chemicals for his laboratory! He amassed over 200 different types of chemicals and labelled them all as ‘poison’ so that no one would interfere with them. Not content with experimenting with chemicals, Al soon graduated to people. He was always fascinated by the flying of birds. How did birds fly? The young Al gave it a lot of thought and finally decided that it must have something to do with their diet. So, he supposedly ground some worms and fed them to one of his friends. Eagerly, the young scientist awaited results which were astonishing but not what he was expecting. His friend groaned with a severe stomach ache and Al got an even more severe scolding from his mother.

Even though his books and experiments kept him busy, Al found plenty of time to question his parents on every topic under the sun. Unfortunately for them, the books that he read made his questions even tougher to answer. When Al started reading Isaac Newton’s book ‘Principia’ he naturally started asking questions pertaining to its concepts and questions which made his parents feel entirely out of their depth. Samuel and Nancy put their heads together and decided to hire a clever tutor to help on their precocious son. However, their plan failed miserably. Al was heartbroken over the language in which Newton’s magnificent theories were written. He thought that the classical aristocratic terms caused unnecessary confusion to the average person and from that time onwards, he developed a hearty dislike for all high-tone languages.

Of newspapers, vegetables, ghosts and more

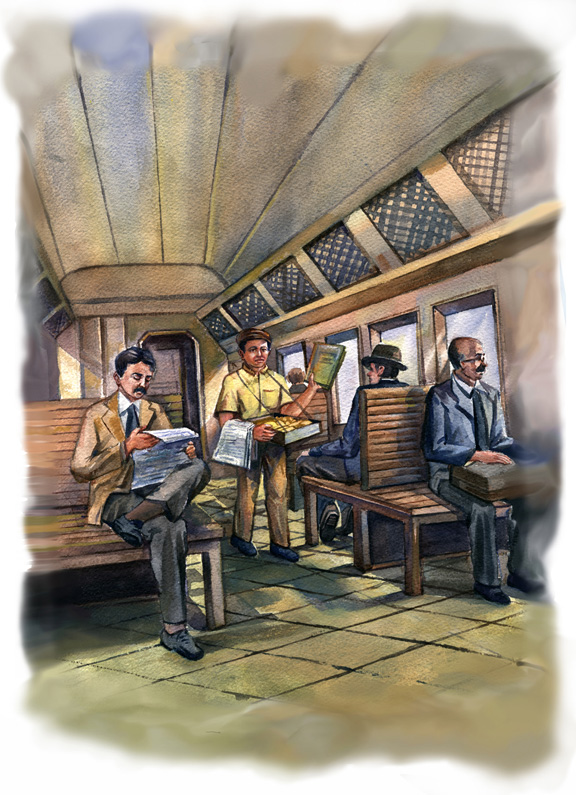

By the time Al turned twelve, he was already an adult. He found helping with the family farm boring and monotonous. So, he talked his parents into letting him work as a newsboy and candy butcher on the Grand Trunk Railroad. He would be up by 6.30 every morning to catch the 7 am train from Port Huron to Detroit. For the next two hours, he would be busy selling newspapers, sweets and magazines on the train.

The return train to Port Huron was not until six in the evening. So, there was a fairly long layover in between. And what did Thomas do with this time? Simple, he read.

Every day, Thomas would visit the Detroit Public Library, of which he was one of the first patrons. He began with the last book on the bottom shelf and would have systematically read every book in the stacks had his parents not wisely guided him into being more selective. He read Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy, Sear’s History of the World and countless books on practical chemistry. Soon he developed a deep interest in English literature. Years later, Thomas’s love for Shakespeare’s plays prompted him to consider becoming an actor but he soon rejected the idea on account of his high pitched voice and his extreme shyness in front of any audience, save the ones whom he was trying to influence into helping him finance an invention. He also became very fond of poetry. His favourite was Gray’s “Elegy in a Country Churchyard”. He would endlessly chant this poem to himself and anyone within hearing distance. His favourite lines were:

The boast of heraldry, the pomp of power,

And all that beauty, all that wealth ever gave,

Awaits alike the inevitable hour.

The paths of glory lead but to the grave

However, with time Thomas started feeling that he worked long inconvenient hours for too little pay. He had to find a way to supplement his income. So, the young businessman put his brains to work and soon came up with an innovative idea. He started buying fresh fruits, butter, berries and vegetables from farmers in small villages en route. He would then sell these items along with his other regular goods at different stops that the train made. He made a handsome profit on it which was even sweeter as he did not have to pay any freight! Very soon, Al had two stalls selling his stock at the Port Huron station and had to hire a few young boys to help him.

Hard to imagine a 12 year old boy showing such business acumen, isn’t it? Of his profits, he gave one dollar a day to the love of his life- his adored mother and used the balance to expand his magazine counters and buy chemicals for his experiments. His business dallying at twelve exemplifies one of his quotes in later life “The three things that are most essential to achievement are common sense, hard work and stick-to-it-iv-ness.”

Thomas was happy and busy. The only part of the day which he hated was the drive back to his home from the Port Huron station. There was a stretch of dark woods on the way which was the site of the soldier’s graveyards. The woods petrified him and he would whip his horse, close his eyes, and boy and horse cart would thunder down the road. Ultimately, Thomas realized that nothing happened to him over the way and he lost his fear of the dark and the dead. He recalled this period as the happiest in his life. “I was just old enough to have a good time in the world but not old enough to understand any of its troubles.”

Thomas had been a newsboy for over a year now. He missed working in his home laboratory as he had so little time to spare. Also, by this time his long suffering mother had started complaining about the smells and dangers of all the poisons which he kept accumulating in it. One day, it dawned on him that there was a lot of empty space in the baggage car in front of the train. “Couldn’t he use it for a laboratory?” He excitedly ran to enquire from the conductor. The conductor who was a friendly Scotsman readily granted him the permission. Thomas was jubilant; with one stroke he had solved all his problems!Soon,he had transferred his whole kit and caboodle to the baggage compartment in the train. Throughout the year 1861, Thomas spent many a happy days working away in his moving laboratory, which was incidentally the first of its kind.

The first risk

The year 1861 marked the beginning of the civil war in America. Newspaper business was brisk as people anxiously waited for the war news. Every afternoon, the newsboy Thomas would put in an order for a certain number of copies for the Detroit Free Press newspaper, generally around 200. The lad soon noticed that on the days when the newspaper contained a strong headline related to the war, he sold more newspapers. Soon, he began visiting the Free Press building early in the afternoon to find out in advance about the day’s headlines. This helped him to make a more accurate judgement about the number of copies which he could sell.

One day in April 1862, Thomas was in time to hear the telegraphic report on the battle of Shiloh. He learnt that the day’s newspaper would contain a large headline about the massacre at Shiloh.Thomas thought, “Wouldn’t I sell lots many newspapers if people along the route knew this headline?” His fertile mind soon came up with an idea and he rushed to the telegraph operator. Quickly Thomas told him his plan. If only the telegraph operator would wire the headlines to other train stations from Detroit to Port Huron, the telegraphers along the route would write out the headlines on the board. By the time, Thomas would arrive with his newspapers, people would be eager to hear the news and hence would buy the newspapers.

“Well Thomas”, the telegrapher said“you might be right but I don’t know whether I should.”

Thomas fixed the telegrapher with his penetrating stare and tried again, “Please Sir, couldn’t you help me? I am willing to pay for it. You can have these fresh strawberries or some of this candy or even this magazine, anything that you want.”

The weary telegrapher studied the grave young boy for a moment and sighed “Very well. You have got a deal.”

The jubilant lad then fearlessly went up to the managing editor William Storey. “Mr.Storey” began Thomas “I would like to order a thousand copies for this afternoon.”

The editor looked at the shabby young boy and remarked “Boy, isn’t it quite a bit more than your usual order.”

“Yes it is,” owned Thomas “but I believe I can sell it.”

“Are you sure?” asked Mr. Storey.

“Yes sir, I am”replied the determined lad.

“Then the papers are yours. Best of luck” smiled the managing editor.

With a quick word of thanks, the nervous boy set off with his precious burden to board the train. But he need not have feared. Huge hordes of people were anxiously waiting for the newspaper. Thomas was entirely sold out even though he had hiked up the price appreciably!

A brilliant idea, a setback and a disaster

At 15, the enterprising Thomas got a new inspiration. With his newsboy savings, he bought a second hand printing machine and some ‘type’ used for printing and added his printing press to his laboratory in the train compartment. Soon, Thomas was printing his own little newspaper which he called ‘The Weekly Herald’. His brilliant little newspaper was full of local news and gossip and also reported railroad service, births, deaths and retirements. Thomas quickly lured 300 commuters as subscribers to his paper. Fortunately for him, his readers did not mind his incorrect spelling. For instance:

We were informed that Mr. Eden is about to retire from the Grand Trunk’s eating-house and Point Edwards…. We are shure that he retires with the well wishes of the community at large.

Later, he lengthened the gossip section of the paper. One day, he wrote a gossipy article about a well-known Port Huron man. When the embarrassed and furious man saw Thomas, he threw him into the chilly St. Clair River! The cold water dampened the enthusiasm of the young editor and the printing press was quickly shut down. Thomas returned back to his laboratory and experiments. But as it is rightly said, it never rains but pours. Just like his mother, the train conductor was getting fed up with the laboratory, its nasty smells and the customer complaints regarding it. One day, unknown to Thomas, a bottle of phosphorus came undone when the train gave a sudden jerk. Due to this jolt,a stick of phosphorus rolled on the floor and ignited. The furious conductor scolded Thomas soundly and not content with that he threw him off the train along with all the contents of his beloved laboratory. The poor lad was grief stricken at the fall of his fortunes.

Around this time, Thomas became totally deaf in his left ear and lost eighty percent of his hearing in the right. There are several theories behind its likely cause. Some believe it to be the after effects of scarlet fever which he had as a child. Others blame it on the conductor who supposedly boxed Thomas’s ears after the incident of the phosphorus fire on the train. Whatever the reason, Thomas never worried unduly about it. Naturally inclined towards accepting whatever fate threw at him, he quickly adjusted to things which he felt were beyond his control and always found alternative ways to compensate. Interestingly, years later when Thomas acquired the means to have an operation that would have likely restored his hearing, he refused. His rationale: he feared that he would find it difficult to relearn how to think in an ever noisier world! The one sound that he missed hearing was the chirping of the birds. In later years, he acquired an aviary containing 5000 birds.

A new beginning

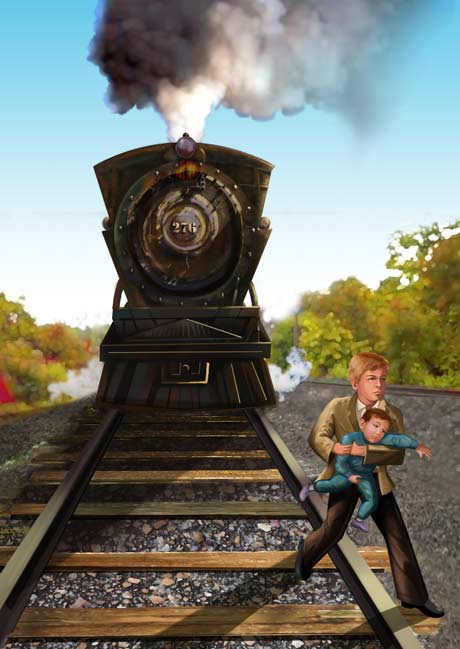

Thomas was now fifteen. Life was going on in its usual way until one fine day in August.Thomas was at Mt. Clemens railway station.Absently watching the station master Mackenzie’s four year old son Jimmy at play when the child accidentally wandered on the train tracks right in front of an oncoming box car. Quick as lightning, Thomas leapt forward and rescued the little boy though his heels were cut by the wheels of the train.

“Thomas”, sobbed the grateful father “I can’t thank you enough for what you have done. I can’t give you anything much but would you like to learn the Morse code and telegraph?”

Thomas was speechless. In those days, knowledge of the Morse code and telegraph was like possessing knowledge of how to use a state-of-the-art computer!

Morse code is a method of transmitting text information as a series of on-off tones, lights, or clicks that can be directly understood by a skilled listener or observer without special equipment

“Yes Mr. Mackenzie” replied the jubilant Thomas “I would like that very much.” And so began Thomas’s telegraphy education. He spent long hours practicing beyond midnight and finally mastered the Morse code.

Armed with his knowledge of the Morse code, Thomas landed his first job as a telegrapher for the Grand Trunk Railroad at Stratford Junction, Ontario at sixteen. He used to work the night shift as it left the day free for his experiments. Thomas’s supervisor who was a very conscientious man unwittingly gave him the inspiration for his first unofficial invention. To ensure that they stayed awake on the job, all telegraphers were required to send a short message to the central office at the stroke of every hour. The number for this message was ‘6.’ This annoyed Thomas who wanted to catch up with his sleep which got sadly neglected in the day owing to his experiments.Very soon, he came up with an idea to one up his supervisor.

The young inventor created a device which automatically ‘reported in’ at the stroke of each hour. This worked well for a while but soon his supervisor got suspicious as, though the ‘6’ message from Thomas’s end appeared exactly on time, but he failed to respond when messages were sent to his office. Eventually, the supervisor came to know about Thomas’s invention and he banned him from using it. He was not fired though as good telegraphers were hard to find and Thomas was probably one of the best. The firing happened a little later when Thomas failed to pass orders to a freight train which almost caused a head-on collision.

The young and merry telegrapher

Once the civil war ended, Thomas announced his intention to set out into the world and seek his fortune. His mother did not like the notion but she gave in to her son’s wishes. With a heart full of hopes, Thomas started out from home. Over the next few years, he wandered through the south and the Midwest as a tramp operator. Having worked in many a company and many a ‘moonlight’ experiment later, the young nomad invented a device which he called the ‘automatic repeater.’ This device would automatically transmit telegraph signals between unmanned stations, allowing virtually anyone to easily and correctly translate codes at their own speed and convenience. Oddly, Thomas never patented this device.

However, Thomas’s moonlighting caused him a lot of grief as well. None of his employers looked favourably on it and it was prohibited, but obedience did not come naturally to Thomas Alva Edison. In 1867, his moonlighting lost him his job with the Louisville arm of Western Union. The employees there were forbidden to meddle with discarded equipment but Thomas unabashedly went on with it. He once remarked, “Hell, there are no rules here – we’re trying to accomplish something.” One day, while working on lead-acid batteries, he accidentally spilt sulphuric acid right on his superior’s desk. Needless to say, he was fired!

At the age of 21, Thomas returned back home ragged, dirty and penniless. He was dismayed to find the change in his home. His mother was beginning to show signs of insanity and his father had just quit his job. To make matters even worse, the local bank was about to foreclose on their home. Typical of him, Thomas quickly came to grips with the situation and decided that the best thing to do would be to set out and earn a living to help out his parents. With him, to think was to act. He promptly requested his friend Milton Adams, who was then working in Boston to help him find a job. Milton asked him to immediately come to Boston. Thomas was soon on his way to Boston. His swift departure was prompted in part by the free railway pass provided to him by the Grand Trunk Railroad for some repair work which he had done for them.

Off to Boston

Thomas arrived in Boston in the middle of winter in the year 1868, missing a much needed winter coat. An operator who witnessed him then observed that he was “the worst looking specimen of humanity I ever saw.” The young telegrapher was clad in jeans that were six inches too short for him, a jacket that he had bought off the back of a railroad labourer on his trip across country and a wide-brimmed hat with a tear on the side, through which his ear (most likely his good one) poked out.

In those days, Boston was the hub of budding inventors and entrepreneurs, very much like the modern day Silicon Valley, California. Thomas’s friend, Milton, arranged for an interview with a Western Union superintendent. As part of his job interview, Thomas was assigned to New York No.1 wire and asked to take a report for ‘The Boston Herald.’ The operators who took him for a naive young boy had a good laugh over his unkempt appearance. Deciding to put up a job on the guy from the woolly West, they arranged to have one of the fastest senders in New York send the dispatch and ‘salt’ the new man. But the unsuspicious Thomas easily adapted to the speed of the New York sender. A few minutes into the exercise, he happened to glance at the faces of the other operators and realized that they wanted to muddle him. He waited till the end and then telegraphed the New York operator: “Say, young man, change off and send with your other foot.”

Thomas was selected and placed as an operator at the headquarters of the esteemed company for his brilliant performance. He soon started working and quickly got nicknamed ‘the Looney’, something that we might call a bright engineer or a scientist today. Thomas would work eighteen to twenty hours a day. Intensely curious about the underlying principles of electricity which made telegraphy possible, he was confident that he could greatly improve it. He was extremely careless about his clothes and personal appearance but would likely spend his last dime on books and scientific equipment. Once, he spent $30 on a suit but by the following week the suit was completely spoilt owing to his experiments with acids. Thomas looked at it and simply said “That’s what I get for putting so much money into a suit.”

The young inventor received his life’s first patent in Boston for a device called the ‘electric vote recorder’at the age of 21. Capable of automatically recording votes, the device could speed up the voting process and also prevent counting errors. Unfortunately, his first ever official invention did not go down well with its targeted users. The members of the Massachusetts Legislature, to whom he tried to market this device, were not impressed. They claimed that “its speed in tallying votes would disrupt the delicate political status quo.” What it actually meant was that the politicians would lose the time which manual counting of votes gave them to influence votes. One of the politicians scolded Thomas remarking, “This is exactly what we do not want…Your invention would not only destroy the hope the minority would have in influencing legislation, it would deliver them over-bound hand and foot to the majority.”

Thomas got disheartened by the apparent failure of his first invention but he soon shook it off. He always believed that ‘Every wrong attempt discarded is a step forward.’ On thinking about it, he realized that his invention was well ahead of its time and so did not have any immediate sales appeal. The experience of his electric vote recorder taught him a very important business lesson which he followed throughout his life: “never waste time inventing things that people would not want to buy.”

Thomas kept on improving his knowledge while at Boston. He would often visit and attend lectures at Boston Tech, which later became the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He was also exposed to the ideas of many associates regarding multiplexing telegraph signals. During this time, he also read the works of the British scientist Michael Faraday. Like Thomas, Faraday was self-taught and tended to avoid complex maths in his work. Thomas brought Faraday’s books home early one morning at 4 and read continuously till breakfast time. Before running to breakfast he called out to his friend Milton Adams, “Adams, I have so much to do and life is so short, I am going to hustle.”

Date with the "children"

The young Thomas used to be very shy. Once, the principal of a ‘select school’ for young ladies asked the Boston Union to send someone to display the Samuel Morse telegraph to her ‘children’. Always ready to earn some extra money, Thomas, along with his bosom friend Milton Adams, accepted the invitation. The duo reached the school at the appointed time and readied everything for the demonstration. The principal then ushered her children into the room and in came about twenty young ladies, all over seventeen and elegantly gowned.

When Thomas saw the young girls, it looked as if he would faint. He called Adams on the telegraph line and requested him to come on stage and give the explanations, to which Adams refused. Flustered, he somehow managed to say that since his friend Mr Adams was more equipped with cheek he would make the explanations while Thomas himself did the demonstrations.

Thomas and the cockroaches

An anecdote which displays Thomas’s love for fun and his ingenuity goes like this. The Western Union office of Boston was earlier used as a restaurant and this had left behind a whole army of cockroaches. It was a night time ritual for the cockroaches to come out as bold as brass when the operators set down for their midnight food. Within moments of the lunch boxes being opened, the cockroaches would magically appear and make a fine meal of sandwiches, apple pie and whatever else there was for display. One day two cockroaches landed on Thomas’s lunch box and made a meal of his pie and sandwich. The aggrieved Thomas declared,“Just wait till tomorrow night, and if I don’t paralyze every roach in this building, I’ll eat my old boots.”

Next day, General Thomas came heavily loaded with his arsenal-a roll of tin foil and two heavy batteries. Cutting the tin foil into strips, he stretched them across the table and then connected the strips with two heavy batteries and voila the battlefield was ready for the enemy. One of the oldest operators said in later years, “We awaited the slaughter with morbid interest. One big fellow came up to the post at the southeast corner of the room and stopped for a moment. He brushed his nose with his forelegs and started. He reached the first ribbon in safety, but as soon as his core-creepers struck the opposite or parallel ribbon, over he went, as dead as a free message. From that time until after dinner the check boys were kept busy carrying out the dead.” By midnight the table was chock a full of dead cockroaches. A Boston newspaper enamoured by Thomas’s ingenuity came down to interview him but the manager objected and electrocutions were discontinued by request.

Stop or I'll shoot

Thomas had an insatiable appetite for books. He often bought books at auctions and second hand stores. Once at an auction, he reportedly bought a load of twenty volumes of the North American Review for two dollars. Later he had the books bound and delivered to the telegraph office. One night, when he got off from work after 3 am, he set off at a brisk pace carrying the bound parcel on his shoulder.

Soon, a night watch police officer was hot on his heels. “Stop” shouted the officer. Heedless, Thomas walked on.The officer shouted again but Thomas did not stop. The breathless officer then aimed a few shots at Thomas. When he heard a bullet go whistling by his ear, Thomas stopped. The policeman who had taken him for a robber grabbed hold of him and ordered Thomas “Open that parcel.” The dumbfounded Thomas complied. The officer’s face was a picture when he saw the books.

“Books” he squeaked “why did you not stop when I was shouting at you?”

“I am sorry” replied the contrite lad “you see, I am deaf. I didn’t know that you were shouting at me to stop.”

“Lad, count yourself lucky” huffed the shamefaced officer. “Had I been a better shot, you would now have been dead.”

109 Court Street

In Boston, Thomas rented a lab space at Charles Williams Jr. Telegraph Instruments Company at 109 Court Street. This place was a hub for budding inventors. Bell, Watson, Hall, Ritchie all had rented 109 at some point in their career. In January of 1869, Thomas left his job as a telegrapher and devoted himself full time to his inventions. With time however, he realized that his best chance as an inventor lay in New York. With this in view, he borrowed $35 from his friend, Michael Bredding and sailed for the big apple.

Ahoy New York

Thomas arrived in New York, ragged, shabby and penniless, once again, in the year 1869. Here, he applied for the position of an operator with Western Union,but this was to take some time. In the meantime, he needed a place to sleep. He hunted around and finally made the battery room of the Gold Indicator Company his night time home. This room housed the critical central stock ticker machine which supplied gold quotes on a real time basis for similar systems installed in individual brokers’ offices. The moonlighter Thomas snooped around quite a bit and studied all the equipment in the room.

By the third day after his arrival, Thomas was almost on the verge of starving to death when the magic began.Thomas was idly sitting in the office, when suddenly there was a loud bang and crash and the mighty stock ticker came to an abrupt halt. Within moments, all was in confusion. The room was filled with over three hundred boys from the offices of the numerous brokers on the street, all yelling at once that a such and such broker’s wire was not working and had to be fixed immediately. The man in charge of the repairs completely lost his mind and was of no help. Soon, the chief of the office came rushing in.

“What is going on?” he asked the repairman. The bemused repairman seemed to not know how to speak.

“Please sir” shouted Thomas over the babble “I can fix the machine.”

The aggrieved chief looked at him and bellowed,“Fix it! Fix it! Be quick!”

Thomas regarded the ticker for a minute and then deftly manipulated a loose string back to where it belonged. Within minutes, the room was empty as the boys scattered to their various offices. In less than two hours, everything was back to normal! The chief of the Gold Indicator Company asked Thomas to come and see him the next day. When the clueless lad arrived at his office, the chief immediately offered him the position of consulting electrician and mechanic for a monthly pay of $300! For a moment, Thomas was in shock as the change in his fortunes was so sudden and when the news finally sank in he vowed to live up to his magnificent salary even if he had to work for 20 hours to do it. For the young inventor this incident was more ecstatic than anything in his life as it made him feel as though he had been suddenly delivered out of abject poverty and into prosperity.

The first cheque - ecstasy and paranoia

Warm, well fed and with a roof on his head, Thomas soon resumed his old habit of moonlighting and tinkered with the telegraph and the stock ticker. Very soon, he devised an improved stock ticker which he called the universal stock printer. The beauty of this device was, that if a particular stock ticker should go out of sync in a broker’s office and start printing wild figures, it could be directly corrected from the central station saving lots of trouble for the broker and the centre. Thomas exhibited this device to General Lefferts, the President of the Gold and Stock Telegraph Company.

Thomas had thought long and hard about the payment that he should receive for his invention. Considering the amount of time and maniac energy which had gone into its making, he thought that he should get at least $5000; at the lowest he would settle for $3000. During his early days of invention, he estimated the value of his invention in terms of time and effort he had spent on it and not the wealth that it would generate for the purchaser.

“Well, young man” said General Lefferts “how much do you want for your beautiful machine?”

Thomas shifted from foot to foot. He felt that the amount which he wanted for his machine was too much. “General” said Thomas “why don’t you make me an offer?”

The General said “How would $40,000 strike you?” Thomas felt close to fainting but managed to say yes. Soon he had his first cheque for $40,000 drawn on the Bank of New York, at the corner of William and Wall Streets.

As if in a dream, the young inventor went to the bank and passed his precious cheque to the paying teller. The teller said something to him which he could not hear owing to his deafness and then the teller returned his cheque to him. The dismayed Thomas felt that he had been cheated in some way and went outside to the large steps to let the cold sweat evaporate. He then went back to the General, who burst out laughing and told him that the cheque must be endorsed and sent a young man to help him. Finally, Thomas encashed his cheque and proceeded to solemnly stow the bundles of money into all his pockets. He stayed awake all night long with the cash laid out on his bed, counting it again and again, scared out of his wits that someone would steal his money. The next day, with the help of the General he deposited his money into the bank and opened a bank account.

A few weeks later he wrote to his father: “How is mother getting along?…I am now in a position to give you some cash… Write and say how much… Give mother anything she wants…” He also returned the $35 which he had borrowed from Bredding.

Meet Mr. Edison - The Inventor

The sale of the universal stock printer was a landmark event in Thomas’s life. It sealed his reputation as an inventor, made a deep impression about his ingenuity and ability and brought him to the notice of the who is who of the financial circle. Never one to sit on things, Edison quickly invested his money into a shop, machinery and men where he would manufacture stock tickers for General Lefferts. During those days, he worked with feverish energy and doled out invention after invention. Edison believed, that one third of life which people spent in sleeping was a sheer waste of time and he himself managed with three to four half hourly cat naps.

As business flourished, he hired a bookkeeper. After the first three months, Edison asked him “How much money have we made?”

The bookkeeper checked his books and replied “Sir, we are $3000 in the black.”

“Boys” announced the delighted boss “dinner’s on me tonight.”

Two days afterwards, the bookkeeper presented himself with a doleful air and began “Sir, I had actually made a mistake that day.”

“That’s all right” replied Edison “how much have we actually made?”

“Nothing” said the bookkeeper “We have lost $500.”

Within a few days, he came back to Edison again and told him that he was all mixed up and that they had actually made over $7000. The exasperated Edison changed bookkeepers, but never again counted his profits until he had paid off all his debts and had the profits in his bank account.

Soon, work of all kinds began to descend on the young inventor who was also busy with his own plans and inventions. In October 1869, Edison formed the company ‘Pope, Edison and Co’ with his colleagues Franklin Pope and James Ashley. This firm was dedicated to the construction of electrical devices. In 1870, he founded ‘The American Telegraph Works’ and took centre stage in the distribution of financial information. In 1871, he started designing perforators, ink recorders and typewriters. In 1872, Thomas conducted tests of his automatic telegraph system on the lines of the Automatic Telegraph Company thereby establishing himself as an irrepressible genius in the telegraph industry.

Death of his perfect fan

On 9th April 1871, Thomas’s mother Nancy passed away. Nancy Edison played a very big part in her son’s success. Many people questioned her decision to give a twelve year old boy the freedom to come home at eleven thirty at night after selling newspapers on a train. Yet she did. She had complete faith in her child and guided him gently without restricting his freedom to think for himself. Had it not been for his mother, maybe the genius in Edison would have been stifled even before it got a chance to blossom. Maybe Edison would have lost faith in himself and gone through life believing that his brains were addled and the name Thomas Alva Edison would have never become famous. Edison was fully aware of this and always said that “The memory of my mother is a blessing to me.”

Man and wife

Perhaps as a reaction to his mother’s death, Edison soon got romantically involved with Mary Stilwell, a 16 year old employee who worked at his News Reporting Telegraph Company. The young couple got married within a few months of dating on Christmas Day in the year 1871. Though Edison clearly loved his wife, theirs was not a very happy marriage. Edison’s obsession with work and Mary’s constant illness drove them apart. Mary could not understand her husband’s work which disgusted Edison. He wrote in his notes that his wife could not invent worth a damn. Even after getting married, Edison would often sleep in the laboratory and spend most of his time with his colleagues. Nonetheless, their first child, Marion, was born in February 1873, followed by the birth of a son, Thomas Jr., in January 1876. Edison fondly called them ‘Dot’ and ‘Dash’ referring to telegraphic terms. Their third child, William Leslie was born in October 1878.

Quadruplex telegraph

In 1874, Edison began work on developing the quadruplex telegraph. This was a landmark invention of that era as it made possible the transmission of two signals in two different directions through the same wire. He successfully tested the quadruplex telegraphy on the Western Union Telegraph Company lines between New York and Boston with an intention of selling them the invention. However, the President of Western Union, William Orton, though keen to close the deal with Edison went on a long tour. Edison who at that time was deeply in debt, desperately needed funds and so, when in January 1875, Jay Gould, the owner of the Southern and Atlantic Telegraph Co. lured him with an attractive offer of $30,000, Edison sold him his invention. Later, Jay Gould breached the terms of the contract and this led to a protracted legal battle for the settlement of dues. But a tough minded Edison took this in his stride and continued on his invention spree.

In November 1875, Edison discovered the phenomenon of ‘entheric force.’ This principle was based on the discovery that electrically generated waves could traverse an open circuit. This was an unimaginable and outlandish idea at that time and his fellow inventors ridiculed it. Eventually, this interesting phenomenon laid the foundation of wireless telegraphy.

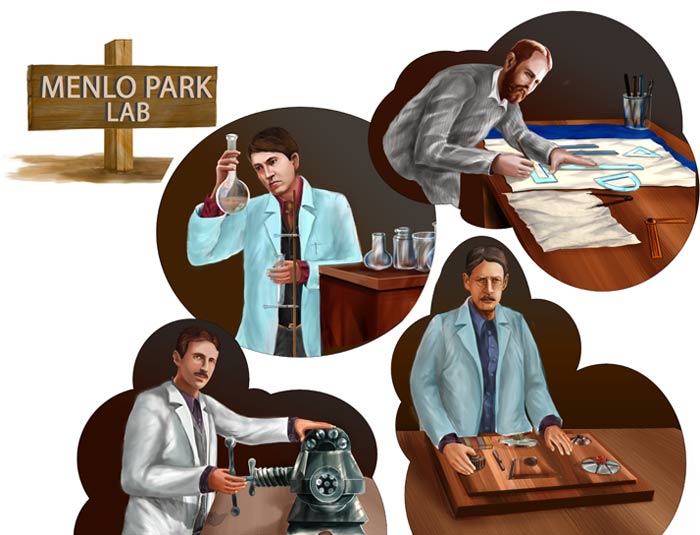

Enter the wizards tower

Edison, who was now 29, finally had the resources to fulfil his dream of building a laboratory where he could experiment to his heart’s content. He had come a long way from his candy butcher days and his makeshift laboratories in the train compartment. After a long search, he finally decided to construct his laboratory at Menlo Park, New Jersey. In 1876, he entrusted his father and a few trusted aides the task of constructing the greatest invention factory ever. This laboratory earned him the nickname ‘the Wizard of Menlo Park.’

Menlo Park was a very small hamlet. Apart from Edison’s laboratory, it had only seven houses, of which, the best looking house was Edison’s. This place had a windmill that pumped water into a reservoir. It is reportedly said that Edison had his front gate connected with the pumping plant in such a manner that whenever any visitor opened or closed the gate he involuntarily added to the supply in the reservoir.

The invention factory consisted of a laboratory building, a machine shop, a carpenter shop and a gasoline plant. Edison wanted his laboratory to have a stock of almost every conceivable material. A newspaper article printed in 1887 proves how serious this claim actually was, noting that the laboratory contained ‘eight thousand kinds of chemicals, every kind of screw made, every size of needle, every kind of cord or wire, hair of humans, horses, hogs, cows, rabbits, goats, minx, camels…silk in every texture, cocoons, various kinds of hoofs, shark’s teeth, deer horns, tortoise shell…cork, resin, varnish and oil, ostrich feathers, a peacock’s tail, jet, amber, rubber, all ores…’ and the list goes on. Over his desk, Edison hung a placard with Sir Joshua Reynolds famous words: “There is no expedient to which a man will not resort to avoid the real labour of thinking”. This slogan was reportedly posted at several places throughout the facility.

Edison hoped to turn out a minor invention every ten days and a big thing every six months or so.Though Edison and his team worked hard, the atmosphere at the factory was far from grim. He encouraged an informal work environment where there were no rules. Many a times as the team worked on into the night Edison would halt the work and call for refreshments. Everyone would knock off work, join in the meal and share a story or joke. Edison would often work up to three or four in the night and then curl up on one of the laboratory tables with a couple of books for a pillow.

Sometimes one or other of the laboratory assistants would be found asleep on a table in the early morning hours. If they snored too loudly, those still at work would use the device ‘calmer’. This device consisted of a Babbitt’s soap box without a cover. A broad ratchet-wheel with a crank was mounted on it, while into the teeth of the wheel there played a stout, elastic slab of wood. This box would be placed on the table where the snorer was sleeping and the crank turned rapidly. It made an enormous noise and the sleeper would immediately wake up with a jerk, much to the hilarity of the others.

Of sound machines

Miffed that a fellow scientist Graham Bell had beaten him in the race to invent a telephone, in 1877 Edison developed the carbon telephone transmitter. This transmitter helped to make Graham Bell’s fantastic new telephone fit for practical use. For over a century, the carbon transmitter was used in telephones, radio broadcasting and public address systems. Western Union was forever prompting Edison to invent a communication device which could compete with Graham Bell’s telephone. But Edison never did any such thing and instead went ahead and invented just the opposite – the phonograph, the talking machine. The phonograph was his favourite invention. He reportedly said, “I’ve made some machines; but this is my baby and I expect it to grow up to be a big feller and support me in my old age.”

The phonograph was the result of years spent experimenting with the telephone and the telegraph. It made use of his famous tin foil which covered a cylinder and a mouthpiece attached to a moveable arm. In August 1877, he gave the world its first talking machine. The first phrase the machine replayed to an ecstatic Edison was “Mary had a little lamb.”

The whole world could not stop talking about Edison’s talking machine.

And then there was light...

The world which Edison lived in was radically different from the world that we know today. Gas lighting or coal gas was the predominant source of light. It was dirty, unhealthy and liable to explosions. However, people were used to having it in their homes. Many people had worked on developing a suitable substitute for it without much success, until a certain genius called Edison entered the field in the fall of 1877. The wizard soon concluded that the answer to the gas light lay in developing an electric light which would give light by incandescence. An incandescent light is one which produces light with the help of a filament wire which is heated to a high temperature by passing an electric current.

Edison began his experiments on light at a time when the world around him had concluded that it was impossible to produce light by incandescence. Never the one to believe anything until he had proven it himself, Edison turned them a deaf ear [literally!] and threw himself heart and soul into developing just such a lamp. He went one step ahead and stoutly declared to the press that he would very soon develop a cheap and long lasting electric light.

The wizard had his work cut out for him. To make a practical electric bulb, it was essential to first hunt out a filament which would last for long. To this end, Edison and his team did thousands of experiments on different kinds of filaments to find the perfect one. He reportedly sent his researchers to South America in search of exotic fibres where they had to brave hostile natives, poisonous snakes and wild animals.

In the end, however, Edison found what he was looking for right in his laboratory – a common spool of thread. When he baked this, it stiffened and carbonized. This spool of thread was then used to make the first light bulb. Finally, almost one and a half years after his rash declaration, Edison lit his first electric bulb. The work was challenging and plagued with difficulties but giving up was not a part of Edison’s nature. Gifted with an extraordinary amount of patience and perseverance, he once said, “If I find 10,000 ways something won’t work, I haven’t failed. I am not discouraged, because every wrong attempt discarded is another step forward.”

The incandescent light bulb was ready but it was far from perfect and Edison would not and could not rest until he had perfected it. He now experimented by creating a vacuum inside the bulb to see if it would last longer. Accordingly, all the oxygen was pumped out of the bulb. But this was not successful; the bulb imploded as the surrounding air pressure pushed in on the empty space. Undeterred, Edison proceeded to fill the inside of the bulb with helium, an inert gas which is known for its non-reactivity. And hey presto! The bulb burned and burned and burned until the fortieth hour when its light gave out!

Where art thou, oh perfect filament!

The businessman in Edison knew that his bulb needed to last much longer than 40 hours if it had to make it commercially successful and prove his detractors wrong. He could not afford to let his invention join the long line of failed incandescent lights. He and his team searched feverishly for the perfect filament and experimented with boxwood, rosewood, coconut hair and shells, different kinds of thread coated with tar or lampblack, grasses, etc. Mr.Mackenzie who first taught telegraphy to Edison, even plucked a hair from his beard for Edison’s filament experiment. Agents were sent to far off places to hunt for likely materials.

His contemporaries would shake their head over his endless search for the perfect filament and denounced it all as a complete waste of time. What they failed to realize was that it was all good publicity. But Edison did. The showman would make it a point of being on the pier whenever any of his researchers returned home and then with the public and press watching, he would loudly ask the man about his results. Finally, after searching over 6000 species of bamboo, a contract was signed with a Japanese bamboo grower near Kyoto; this was used for developing Edison’s new bamboo filament light bulbs. The first public display of Thomas Edison’s incandescent lighting system was on New Year’s Eve, 1879. The Menlo Park laboratory complex looked luminescent, decked with around 400 glowing lights.

But Thomas Edison’s foray in electricity did not end with the light bulb. Rather it began with it. On September 4, 1882, Edison went ahead and started the first commercial power station on Pearl Street in lower Manhattan. It provided light and electric power to customers within one square mile area. Initially, this utility served power to only 59 customers but towards the late 1880s, the power demand for electric motors brought the industry to 24-hour service from the initial night time lighting and raised the demand for power manifold. Small power stations soon sprung up in many US cities. However, each was limited to an area of a few blocks because of transmission limitations of direct current (DC) which was used in all Edison stations.

Brockton

Even though Edison’s free light bulbs which he felt obliged to provide to his earliest customers had grown quite efficient, the two wire feeder system which was being used to generate and transmit electricity, left a lot to be desired. The New York facility faced numerous black days on account of wire resistance, fuse problems and voltage drops. Also, both the customers and workers were sometimes injured. The fantastic little light bulb was facing all the flak when actually, the generation and transmission system was to be blamed.

Edison was being buffeted from all directions. The press mercilessly targeted him; eminent scientists were still questioning his ability to come up with a feasible substitute for gas lighting and the owners of the gas lighting industry kept coming up with tricks to divert or undermine his efforts. On top of everything, he was constantly worried by the declining health and impending death of his wife Mary. While many a lesser men would have lost their nerve in such circumstances, the irrepressible inventor doggedly pressed on.

However, lady luck was not done playing games with Edison. A British scientist, Dr Joseph Hopkinson, declared that he had discovered a fundamentally new and better method of making and delivering electricity. Hopkinson had been hired to formally evaluate Edison’s first attempt to establish a commercial facility in London but it turned out that he had covertly been doing a lot of fooling around with it. It was his claim, that if his three wire technology was teamed with Edison’s state-of-the-art feeders and transformers, the new system would be able to transmit to sixteen times more area than any of Edison’s existing systems. Edison knew that the three wire system beat his old two wire system hands down. So, he made yet another of his shrewd business decisions -he went ahead and acquired the new technology from Hopkinson.

Unfortunately, Edison could not pilot the three wire technology in New York. For one thing, over 60 tonnes of the old type of wire (or 90% of the planned total 70,000 feet) had already been installed beneath the New York streets and for other, the 3-wire technology still needed many practical finishing touches. More importantly, most of his chief investors would not hear of wasting any more money or time in completely redoing the old system. Edison chose Brockton, Massachusetts to test the new system and the new plant was inaugurated on 1st October, 1883. Unlike the New York Corp, which did not turn out a profit for quite a few years, the slick Brockton facility was recognized to be a profit making venture right from the start.

Edison who seemed to thrive on pressure was at his most productive during these days. During this period, he applied for what was and still stands as not only the greatest number of electrical generation and distribution patents anyone ever produced but the greatest number of patents of all types ever issued to any individual or corporation within a span of six months.

Edison finds his soul mate

Edison’s professional success at this time was marred by a heavy personal loss. His wife Mary passed away on August 9, 1884 of unknown causes, possibly from a brain tumour or a morphine overdose. After Mary’s death, Edison left Menlo Park and settled down with his children in New York. A year later, while holidaying at a friend’s house in Winthrop, Edison met the young Mina Miller and immediately fell in love with her. Mina and Thomas got along like a house on fire. Thomas taught the Morse code to Mina and they would talk in secret, even when others were present. Unlike his first wife Mary, Mina had more worldly education and was well suited to become an inventor’s wife as she came from a similar background.

Thomas and Mina were married on 24th February, 1886. The couple moved into Glenmont after their honeymoon in Florida. The young Mrs. Edison, aged twenty, did not have an easy life. There was less than ten years difference between her and her stepdaughter Marion. Also, Edison was not an easy husband. He could not be cured of his habit of staying all hours at his laboratory and would often forget birthdays and anniversaries. Yet he loved his “Billie” as he used to call Mina. A note found in one of Mina’s books reads, “Mina Miller Edison is the sweetest little woman who ever bestowed love on a miserable homely good for nothing male.” The couple had three children – Madeleine, Charles and Theodore.

West Orange

A few months post his marriage, Edison decided to build a factory within walking distance of his new home. The state-of-the-art laboratory opened in November 1887. The laboratory housed everything that Edison would ever require. The main building had a power plant, machine shops, stock rooms, experimental rooms and a large library (The library was Edison’s favourite place, it even had a cot where Edison used to sleep for some time after hours of intensive study). Aside from this, the premise also housed a Physics lab, a Chemistry lab, a metallurgy lab, pattern shop and a room for chemical storage.

The large size of the laboratory enabled Edison to work on any project that he fancied and also allowed him to work on as many as ten or twenty projects at one time. Edison kept adding and modifying the facilities as per his changing needs. Over the years, factories manufacturing Edison’s invention were constructed around the laboratory. The entire set up ultimately covered more than twenty acres and employed 10,000 people at its peak during World War One!

The birth of General Electric

In 1889, Edison’s various companies were reorganized into a large conglomerate called Edison General Electric. Despite the use of his name in the title, Edison never controlled this company. The huge amount of capital needed to develop the electricity industry had made the involvement of investment banks such as J. P. Morgan inevitable. Later in a clever move in 1892, Edison General Electric was merged with its leading competitor Thompson Houston. Edison was dropped from the title and the company was named General Electric.

War of currents

The wizard of Menlo Park seemed to have a penchant for falling into trouble. As the reader will recall, Edison used the DC current for generating and transmitting electricity. What exactly is this direct current or DC? DC is an electric current that flows in one direction only, as opposed to alternating current or AC that reverses direction in a circuit at regular intervals. This rival technology, the AC current, was introduced by George Westinghouse and Nikola Tesla. Electric supplies were then in their burgeoning stage and much depended upon which technology was used to power homes and businesses. AC current was inherently better than DC as it could traverse larger distances, courtesy its high voltage which could be easily altered as per end user requirement. DC current, on the other hand could be transmitted only to areas within a radius of 2.4 km of the generating station.

Much was at stake, not only for Edison but also for his financial backers. Edison had to prove the supremacy of DC over AC even though he knew in his heart that AC current was better than DC any day. Nonetheless, the shrewd inventor and his financers began an aggressive and unscrupulous campaign of mudslinging against the AC current and its propagators. Edison set about proving that AC current was unsafe for use. With this in end, he held a public demonstration at his West Orange laboratory in 1887.A 1000 volt Westinghouse AC generator was set up attached to a metal plate. A dozen animals were killed by placing them on an electrified metal plate. This episode generated a lot of publicity which was exactly what Edison wanted and a new term ‘electrocution’ was coined to describe death by electricity.

In June 1888, electrocution was established as New York State’s official method of execution but as two designs of the electric chair existed, AC and DC, it had to be decided which one was to be used. Edison went all out to promote the AC current as he felt that no one would like to use the electric service which was used for killing, in their homes. Edison held public demonstrations where he showed that while DC current left the animals tortured but not dead, AC current killed the animals swiftly. In the end, AC current was chosen for the state-wide prison system. This might have something to do with the fact that the head of the committee which was to select the preferred current for electrocution was on Edison’s payroll.

On January 1, 1889, the world’s first electrocution law fell into effect. Westinghouse protested against it and declined to sell any AC generators to the prison authorities. Edison was only too happy to supply the necessary AC generators needed to work the first electric chairs. Westinghouse then funded the appeal of the first prisoners sentenced to death through electrocution on the grounds that “electrocution was cruel and unusual punishment.” Edison testified that death through electrocution was quick and painless and the electrocution deaths went ahead. Ironically, for many years people referred to death through electrocution as being ‘Westinghouse!’

A pioneer of the recording industry

After the launch of his West Orange factory, Edison shifted his focus back to the phonograph. This project had taken a backseat during the 1870s when Edison had been entirely absorbed with the development of electric light. It was Edison’s dream to bring a phonograph to every American home. The big picture person that he was, Edison developed everything that was needed to make a phonograph work– the records to play, the equipment to record the records and the equipment to manufacture the records and the machines.

Edison was personally involved in the recording of sound despite his apparent hearing handicap. Edison explained: “Even though I am nearly deaf, I seem to be gifted with a kind of inner hearing which enables me to detect sounds and noises that the listeners do not perceive.” In the process of making the phonograph practical, Edison ended up creating an entire recording industry.

Mission Hollywood

While working on the phonograph, the intrepid inventor got the idea to develop a device that ‘does for the eye what the phonograph does for the ear’. As with all his earlier inventions, he ended up developing everything needed to both film and show motion pictures. In his early experiments, he made use of his trusted wax cylinder to record the pictures. In 1889, he handed the project to a young Scotsman, William Kennedy Laurie Dickson. Dickson began work on a camera which used celluloid film. This device was called the ‘Kinetograph’. A viewer for the films was also developed which was called the ‘Kinetoscope’. This was shaped like a box with a viewing piece at the top from which a person could view the motion picture.

By 1893, Edison had begun commercial production of movies in a peculiar shack-studio in his West Orange laboratory, known to his employees as Black Maria. His earliest films lasted for about 20 seconds. The first public demonstration of his movies was given in 1893 at the Chicago World Fair. On 14th April, 1894, the first Kinetoscope parlour was opened at 1155 Broadway, New York.

During 1894-95, the unstoppable inventor synchronized the Kinetoscope image with audio and developed the Kinetophone. Once the Kinetophone was ready, Edison began the search for a suitable motion picture projector. He finally selected Thomas Armat’s Vitascope. In 1896, this device was used to project motion pictures for public screenings in New York City. Edison’s movies included ‘The Kiss’, ‘Fatima’s Dance’ and ‘The Great Train Robbery’ to name a few. His films varied from romantic, sensuous and action packed films with sound and special effects. In 1903, he created a ten minute clip called ‘The Great Train Robbery’ which went on to become a blockbuster of that era. It showed the takeover of a train, then the attack of a telegraph operator followed by bringing him back to life and the villain’s escape. It ended with a thrilling close-up of an outlaw firing a continuous stream of bullets directly in the face of the audience.

Into each life some rain must fall

Even geniuses have their bad days. The biggest failure of Edison’s long and illustrious career was his attempt to find a feasible way to mine iron ore. During the late 1880s and early 1890s, Edison worked extensively in his laboratory and in the old iron mines of north-western New Jersey to develop mining methods to satisfy the insatiable demand of the Pennsylvania steel mills. His aim was to create a separator which could extract iron from unusable, low grade ores.

Despite spending a decade of his life on it and millions of dollars on R&D, Edison was never able to make the venture commercially viable. Finally, he gave up on the idea; by this time he had lost all the money that he had invested. This would have spelt ruin for Edison had he not simultaneously developed the phonograph and the motion pictures.

The vroom vroom battery

Edison’s fertile mind was always brimming with ideas. He now envisioned the creation of an acid less battery. The very idea was scoffed at by his contemporaries. Nevertheless, he began work on the battery in the 1890s, just after the entry of the automobile. At that time, gasoline automobiles were still considered unreliable and the market was ruled by steam and electric cars. However, there was a snag in using the electric car. The lead-acid batteries that they used were extremely heavy and had a very short life as the acid corroded the lead inside the battery.

Edison’s goal was to make ideal batteries for automobiles which were lighter, more reliable and at least three times more powerful than the acid batteries. As always, Edison and his team conducted tests on all sorts of metals and materials, to find the one that would best fit their needs. They finally decided on potassium hydroxide and the new battery was ready by 1903.

As was Edison’s wont, he launched the new battery with a great deal of fanfare. Soon, manufacturers and users of electric vehicles started buying them. However, very soon, stories of battery failures started emerging. Many of the batteries would leak while others lost much of their power in a short span of time. Immediately on hearing about the defects, Edison shut down the factory and began to rework on the batteries. By 1910, production of a new and improved battery which used expensive materials was underway at a new factory near the West Orange, New Jersey laboratory.

However, by the time these batteries entered the market, gasoline engines had become the standard for the automobiles. Though Edison’s dream to make batteries for automobiles was not fulfilled, his batteries, whose main merit was their reliability, soon found use in other applications such as providing back up power for railroad crossing signals and power lamps used in mines. In later years, Edison’s battery turned out to be one of his biggest money spinners.

Don't talk to me about X-rays, I am afraid of them

When Wilhelm Roentgen discovered the X-rays in 1895, Edison’s reputation was already well established. Though Roentgen discovered the X-rays, it was Edison who first discovered its wide scale uses. However, Roentgen did not patent his discovery and instead placed it in the public domain as he wanted all humanity ‘to benefit from practical applications of the same.’

This meant that Edison was free to investigate this new discovery. Most of his early research was dedicated towards improving upon the barium platinocyanide fluorescent screens used to view X- ray images. As was his rule, Edison investigated thousands of materials and finally concluded that calcium tungstate was far more effective than barium platinocyanide. By 1896, the Edison x-ray tube was ready. The new invention was soon exhibited at the 1896 Electrical Exhibition in New York’s Grand Central Palace. The public demonstration was a huge success. The crowd went mad over the chance to see their own bones. When one attendant publicly scoffed that the fluorescent screen was just a sheet of ground glass, Edison called him on the stage and forced him to place his wrist in the fluoroscope to see his bones for himself. Everyone rhapsodized about Edison’s newest invention.

But there was a darker side to it as well, which soon unfolded. One of his assistants, Clarence Madison Dally, suffered adversely from radiation exposure. His condition steadily deteriorated and by 1900, his face and hands were damaged enough to require time off from work. In 1902, his left hand had to be amputated and later four fingers of his right hand went the same way. All these procedures failed to help and Dally died from mediastinal cancer. Clarence Dally was the first person to die from experimentation with radiation.

This incident spooked Edison and he stopped all work on his fluoroscope. He said: “Don't talk to me about X-rays… I am afraid of them. I stopped experimenting with them two years ago, when I came near to losing my eyesight and Dally, my assistant practically lost the use of both of his arms. I am afraid of radium and polonium too, and I don't want to monkey with them.”

Edison and the War

Edison was an elderly man of 67, when World War 1 broke out in Europe in the August of 1914. Undaunted, he still continued working with extraordinary strength and passion in his West Orange laboratory. He was fond of saying that he followed the eight hour day: eight hours in the morning and eight hours in the afternoon!

No one ever dreamed about the role Edison would play in the war, even if the United States had ever entered it. Edison’s company was one of the first to feel the impact of the war. He used up a ton-and-a-half of phenol or carbolic acid each day in his phonograph record factory. His factory was the largest user of phenolic resins in the US and he had only a few weeks supply when the war cut off his shipments from Britain and Germany.

Edison believed that the answer lay in developing a phenol industry in America itself. Experts shook their head, declaring that American coal was neither pure enough nor economic to produce; besides it would take several months to develop an American supply. But Edison absolutely refused to allow his company to become the first war casualty. When no chemical company showed interest in this venture, the indefatigable Edison took the task upon himself. He chose 40 of his staff to work round the clock on three ‘eight hour’ shifts to test and develop a process for producing synthetic phenol. He simultaneously had other crews constructing a plant. Within a month of the initial spadework, the new plant started producing a ton of phenol of better purity than the natural one imported earlier. Another month down, when the plant reached its full capacity of six tons a day, Edison was in a position to sell some of his produce to other users. The astute businessman successfully turned even this grim situation into another ace for himself.

During the early days of the war, Edison’s interest was chiefly limited to wheedle the Navy to adopt his alkaline storage battery for its ships and submarines over the generally used lead-acid ones. The Edison battery was safer, more efficient and longer lasting than the lead-acid battery but it was also three times more expensive than the lead ones. In the fall of 1914, a meeting was arranged between the Secretary of the Navy, Josephus Daniel and Edison at the latter’s West Orange plant. Several months later, Daniels wired Edison: “Have just signed authorization for installation of Edison batteries in L-eight (submarine).”The jubilant Edison responded: “I thought I was some optimist but your telegram will cause the boys around here to lash me to the machinery to keep me from flying.”Over the years, Edison and Daniels became close friends based partly on their distaste for the pomposity of naval bureaucracy.

The wizard enters the war

On 7th May, 1915, Germany torpedoed the British ocean liner RMS Lusitania. Edison, a devout patriot, gave a long press interview on the need for greater preparedness by America. To avert making any military threat, the then President, Woodrow Wilson had made no preparations for the war and had kept the army on its small peacetime basis. In his press interview, Edison emphasized the need to build up a stock of modern weapons, ships and submarines for the country’s defence. Among other things, he recommended the creation of “a great research laboratory, jointly under military and Navy and civilian control”, which would develop new weapons and defences, so that if and when war came “we could take advantage of the knowledge gained through this research work and quickly manufacture in large quantities the very latest and most efficient instruments of warfare.”

Daniels, who was thinking on the same lines as Edison, invited him to head just such a committee. He wrote: “I feel that our chances of getting the public interested and back this project will be enormously increased if we can have, at the start, some man whose inventive genius is recognized by the whole world to assist us in consultation from time to time on matters of sufficient importance to bring to his attention. You are recognized by all of us as the man above all others who can turn dreams into realities and who has at his command, in addition to his own wonderful mind, the finest facilities in the world for such work.”

This is how, the Naval Consulting Board was born. On Edison’s suggestion, two members, each from eleven of the largest engineering and scientific societies in the US were nominated to the committee to give it instant credibility with the public. Edison was confident that the group would ‘far outrank any body of scientists and experts that ever gathered together in any single organization.’ President Wilson acquiesced and told the committee members that he was proud to be able to call on ‘the best brains and knowledge of the country’ for a job which needed all sorts of expert and serious advice. However, quite a few demurred. Franklin D. Roosevelt, who was then Assistant Secretary to Daniels, told his wife: “Tomorrow the inventors come in force, but I am dodging the trip to Mt. Vernon. Most of these worthies are like Henry Ford, who until he saw a chance for some publicity free of charge, thought a submarine was something to eat!”

Edison was named President of this committee, but as he could hardly hear, William H. Saunders, a well-known mining engineer, was elected as the Chairman. To follow the meeting, Edison would have his associate Hutchinson tap messages in Morse code on his knee. In its first year, the committee worked slowly, partly because it did not have any legal status, budget or staff and it was only in August 1916, that the Congress recognized its status and commissioned $25,000 for its operation. Though passionate about helping his country, the stuffy bureaucracy in the Navy and the fact that the Navy pigeonholed or rejected many of his ideas and suggestions disgusted Edison.

It is natural for a person to despise authority who has been a law unto himself all his life. Still, Edison’s contribution in the war cannot be denied. One of his significant contributions was the suggestion that statistics be maintained about the location of ships sinking in order to determine the dangerous areas. He was also instrumental in the development of submarine detectors and gun location techniques. The idea was to predict the direct of the assault so that appropriate counter attack measures could be planned.

Another of his ground-breaking suggestion was the creation of a modern scientific and experimental research laboratory for the Navy which was to be operated by civilian experts. Though the Congress agreed with his suggestion and even sanctioned $1000000 for its execution, there was a bitter fracas over its location. Edison was in favour of Sandy Hook which was near his own laboratory while most of his aides on the Naval Consulting Board championed Annapolis. Edison felt that, if Annapolis was chosen as the location, the laboratory would ultimately be controlled by the Navy. He pointed out to Daniels “that its position at Washington will always be a handicap, and that it will be an expense to the Government without producing any practical results.” In the end, Sandy Hook was not chosen. Displeased, Edison resigned from the board in December 1920.

Edison’s stint with the Navy was rough and stormy. Though, many of his suggestions were quite useful, the Navy was careful not to let him know that. But after its brush with Thomas Alva Edison, the Navy was never quite the same again.

Miscellaneous inventions

If all the devices which Thomas Edison invented were detailed it would become long enough to form a book. The number of patents which he accumulated for his inventions during his lifetime would give a fair idea to the reader. Edison received 2332 patents worldwide for his inventions, of which 1093 patents were received in the United States. Edison dabbled into an astonishing array of areas. From cement to rubber, from the electro motograph to the typewriter, from the dynamo to the electric railway, the wizard did it all.

Lights Gloden Jubliee

The year 1929 marked the golden jubilee of Edison’s invention of the electric light. On the momentous day of October 21, 1929, at ten in the morning, President Herbert Hoover, Henry Ford and Thomas Edison arrived at Smiths Creek Depot in Greenfield on a steam powered locomotive, much like the one on which Edison sold newspapers as a youth.

The Smiths Creek, Michigan Depot was chosen, as it was here that Edison was thrown off a train for causing a fire in the baggage car which housed his chemical laboratory. They were met with a crowd of more than 500 people, roaring their congratulations as the trio stepped off from the train.

After a lavish banquet, Edison, along with his former assistant Francis Jehl, went to work in the reconstructed Menlo laboratory in Greenfield village to recreate the lighting of the first electric lamp. As they worked, Graham McNamee, the NBC radio broadcaster reported to a silent world, “Mr Edison has two wires in his hand; now he is reaching up to the old lamp; now he is making the connection….. It lights! Light’s Golden Jubilee has come to a triumphant climax.”

As the connection was made, the entire building was bathed in light. A plane flew overhead with the word ‘Edison’ and the dates ‘79’ and ‘29’ blazing under its wings. Car horns honked, lights flashed on and off and the world drowned itself in electric light in tribute to Edison. As a part of the grand celebration, Henry Ford officially dedicated Greenfield village to his closest friend Thomas Alva Edison. An emotional Edison, overwhelmed by the showers of admiration bestowed upon him said in his speech:

“Mr President, ladies and gentlemen:

I am told that tonight my voice will reach out to the four corners of the world. It is an unusual opportunity for me to express my deep appreciation and thanks to you all for the countless evidences of your good will. I thank you from the bottom of my heart.

I would be embarrassed at the honours that are being heaped upon me on this unforgettable night, were it not for the fact that in honouring me you are also honouring that vast army of thinkers and workers of the past and those who will carry on, without whom my work would have gone for nothing.

If I have spurred men to greater efforts, and if our work has widened the horizon of thousands of men and given even a little measure of happiness in this world, I am content.

This experience makes me realize as never before that Americans are sentimental, and this great event, Light’s Golden Jubilee, fills me with gratitude.

I thank our President and you all, and Mr Henry Ford, words are inadequate to express my feelings. I can only say to you that in the fullest and richest meaning of the term, ‘He is my friend.’

Good night.”

Black-out

The wizard was getting old now. His constitution was weakening and he was reportedly suffering from diabetes. Though Edison’s body was failing, the old restless energy continued to gleam in his eyes. He would still follow his age old routine of going to his laboratory and conducting experiments. The great inventor was 84 now and watching him it seemed as if he would live forever. The mere idea that the wizard who throughout his life had made the impossible possible could be governed by laws reserved for normal human beings, seemed preposterous and impossible. But for once, the wizard lost to death.

3.24 am. October 18, 1931. Thomas Alva Edison. Dead.

Thomas Edison died at his family home at Glenmont, New Jersey surrounded by his family. His coffin was laid out in the laboratory library for two days for people to pay their last respects to the great inventor. His closest friend, Henry Ford, refused to enter the library as he wanted his lasting memory of Edison to be their final conversation in that room. John Ott, who was Edison’s lab assistant for many years, died soon after hearing of Edison’s death, partly due to the shock.

Employees were allowed first to pay their respects. The governor had sent an `honour guard from the National Guard, but Edison’s long time employees stood by the head and foot of the coffin, day and night. The family had planned to end the public viewing by 11 pm on October 20, but so many people were still waiting that the viewing continued until 5 am on the next day. Around 40,000 visitors came to pay their respects in one day, coming at a rate of 2000 per hour!