Introduction

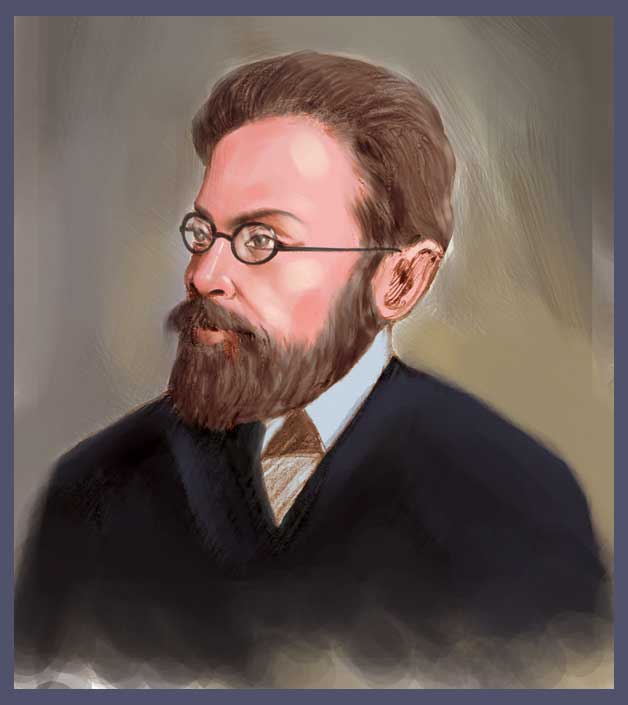

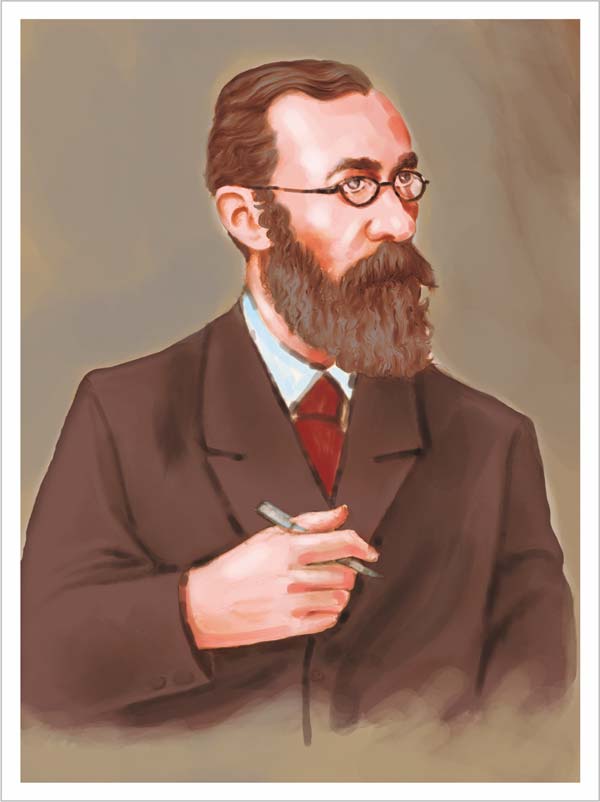

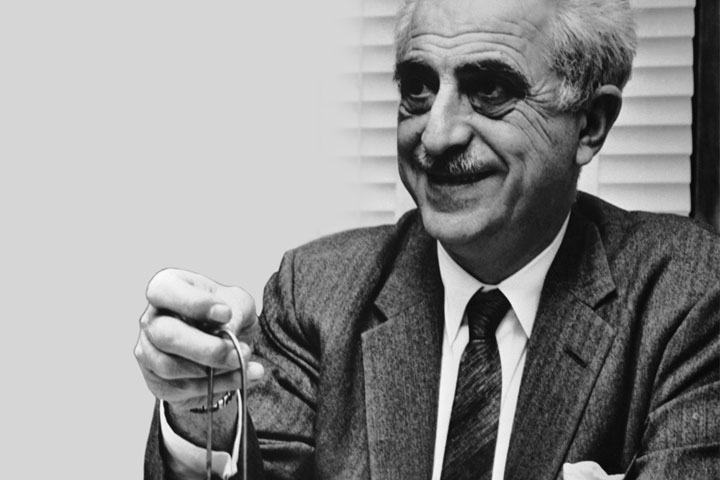

Can you reveal your inner self? With the help of X- rays, yes you can!!! But do we ever ponder about the person who discovered these rays? Though we all are familiar with the term X-ray, the man Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen who made this astounding discovery remains unfamiliar to most of us even to this day. He was not only an intellectual scientist but also a modest human being. He once said, “I didn’t think. I experimented.” The world would have been a different place indeed had it not been for the experimentations of this brilliant observer. His great discovery exposed the internal structure of the body and accomplished the impossible. It not only revealed the mysteries of our body but also turned out to be a ‘boon’ to medical science by detecting our physical disorders. Let us have an insight in to the wondrous life of the man who discovered these ‘phenomenal’ rays.

Disgressed Education

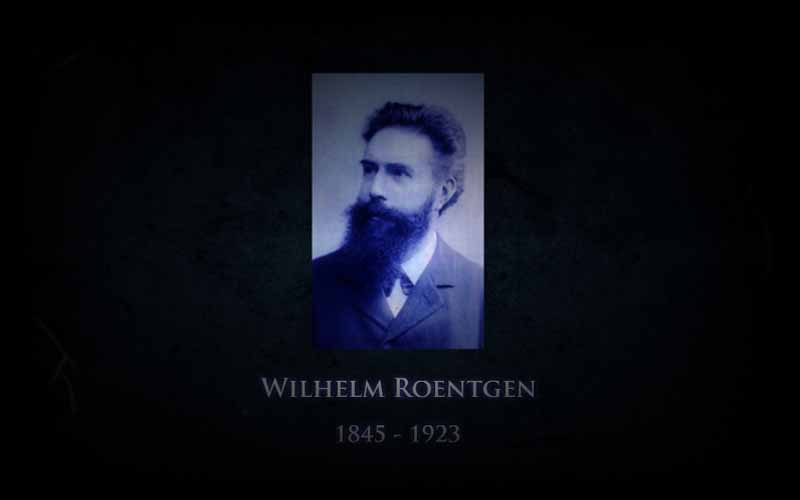

The tale of Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen begins from a small town in Eastern Prussia called Lennep. It was the 27th day of March, in the year 1845, when in an affluent Burgenland style home the adorable toddler named Wilhelm came into this world. Wilhelm was blessed with a reputable father, Friedrich Conrad, who was a local textile merchant and a beautiful mother, Charlotte Frowein, who belonged to a family of traders and merchants. During those days, Prussia was suffering severe political turbulence. Subsequently, on May 23, 1848 when Wilhelm was three years old, his family had to move to the town of Apeldoorn, Holland where his mother’s family had settled. The Roentgens had unfortunately lost the citizenship of Prussia due to their migration but were granted the nationality of Dutch. They now dwelled at 171 Hoofdstraat. In Apeldoorn, Wilhelm was sent to a boarding school where he could not exhibit any exceptional aptitude in studies. Nevertheless, he was always full of passion for nature and would meander in the open country and forests which helped him to be serene with himself.

Since his juvenile days, Wilhelm had a peculiar penchant to create mechanical devices, a characteristic which persisted with him till his last breath. In 1862, when 17 year old Wilhelm arrived in Utrecht, he entered the Utrecht Technical School which was located on Ganzenmarkt. During those days, he lived at 62 Nieuwegracht with Dr Gunning who was an eminent chemist of those times. He was the first one to recognize the spark of concealed talent in Roentgen and guided him to study further. But haphazardly, an incident perpetually ruined his academic endeavours. Once, Roentgen was accused of drawing a caricature of his teacher on the blackboard, but the truth was that Roentgen was innocent and was falsely framed by one of his classmates. Though Roentgen was aware of the true culprit, he denied to divulge his identity and was expelled from the university. Though he was thrown out of the university, he didn’t consider it as a catastrophe. Rather, he tried his luck once again to excel in an entrance oral exam to enter the University of Utrecht. But abominably the examiner was none other than the teacher whose caricature had been drawn in school. As a result, Wilhelm once again paid for his gentle demeanour and was failed in the examination.

Wavering Times

On January 18, 1865, when Wilhelm was 20 years old, he registered at the university to audit some courses. Here he heard of a school in Zurich, Switzerland, that did not necessitate a technical school diploma which he lacked. Finally, after discussing with his parents and gathering their encouragement, he entered the Mechanical Technical Division of the Zürich Polytechnical School. Delighted, he left Utrecht for Zürich on November 16, 1865 and was duly enrolled at the Eidgenssischen Technische Hochschule von Zürich where his quest to learn expanded. In Zurich, his residence was a house at 7 Seilergraben. Meanwhile, he thrived on the technical courses and even took extra hours at the adjacent University of Zürich. Apart from studies, Wilhelm was fond of adventure and would rove in the surrounding mountain hikes. Along with wandering in the mountains he also relished eating at a local inn, Zum Grunen Glas, run by the innkeeper Ludwig. One day while eating at his favourite inn one enchanting waitress caught his eye; it was Anna Bertha, the inn keeper’s daughter. Though Bertha was six years elder to him, there was a spark of love amidst them and immediately the romance began to blossom between them. As happiness surrounded Wilhelm, his grades enhanced and he progressed through his schooling, receiving highest possible marks during his last year. August 6, 1868 was a day of immense delight for him; it was the day when he received his mechanical engineer degree and also proposed marriage to Bertha.

After seizing a degree and Bertha’s hand, he stayed at the University of Zurich. Here he met a man who had an immense contribution in arousing the hidden talent which Roentgen possessed. He was the great experimenter and Theoretical physicist, Dr August Kundt. Roentgen took courses with him and it was Kundt who developed Roentgen’s potential as a Theoretical Scientist. Following Kundt, Roentgen also wrote a dissertation, “Studies on Gases” for which he received his Doctorate in Philosophy from the university on June 22, 1869. Appreciating Roentgen’s potential, later Professor Kundt invited him to assist him in Physics. With Kundt’s encouragement, Roentgen became fascinated with work on gases and further advanced his experimental talents and displayed his excellence as an astute scientific observer.

In the spring of 1870, Kundt was called to the chair of Physics at the Julius Maximiliuns University of Wurzburg, Germany and he invited Roentgen to go along with him. Until then Kundt and Roentgen had become quite close to each other and Kundt decided that he would accept the Wurzburg position only if they would invite Roentgen. Thus, in the fall of 1870, Roentgen accompanied Kundt to the scenic city of Wurzburg on the main river, where they dwelled in comfortable quarters on Vietshchheimer Strasse. Meanwhile, his fiancé Bertha departed for Apeldoorn to learn German cuisine and housekeeping from his mother.

After returning from Wurzburg Wilhelm happily tied the knot with Bertha on Jan 19, 1872 in an elegant home in Apeldoorn. They soon returned to Wurzburg where they settled in a comfortable home on Heidingsfelder Strasse. Wilhelm continued with his experimentations and teachings at the Physics Institute of the Julius Maximilus University on Neubaustrasse. But the institute was shoddily equipped and funded which was quite a disappointment to both Kundt and Roentgen. Therefore, it was a matter of pleasure when both scientists were presented higher positions at the newly refurbished Kaiser Wilhelms University of Strasbourg. On April 1, 1872, Kundt, Roentgen and Bertha moved to the picturesque city in Alsace Lorraine which was then under the German rule. Roentgen continued his scientific investigations to gather data for his examination for the academic level of a Privatdozent(Private lecturer).

During those times, this was one of the steps on the path that a PhD had to travel to obtain the prestige of a salaried professor. Finally, the day of examination arrived on March 13, 1874. After thorough questioning by a board of distinguished scientists, Roentgen excelled with flying colours and was awarded the position of a Privatdozent. Though this position carried no salary, it permitted him to receive fees from students in his classes and also qualified him for appointment as an assistant professor, a salaried position, which was the next step on the academic ladder. People waited for years for their first call, but Roentgen was lucky and got his call just a year later.

On April 1, 1875 at the age of 30, Roentgen was called by the Agricultural Academy of Stuttgart-Hohenheim in Wurttemberg and was offered a full professorship in Physics and Mathematics. He decided to grab the opportunity as this new challenge offered him a salary and also a civil service status. However, he accepted this position with uncertainties, as it meant breaking ties with his family and friends, and majorly with Professor Kundt. The position automatically granted him German citizenship but the accommodations were less than satisfactory for him and Bertha, with a small one room apartment and primitive living conditions. Life wasn’t ensuing the way Roentgen wished it would, but he was content with whatsoever came across his way. Soon good news knocked on his door when in about a year and a half Professor Kundt created a new chair for Theoretical Physics and recommended that Roentgen be called for the position. An overjoyed Roentgen accepted the proposal and with a sigh of relief, he and Bertha returned to Strasbourg on October 1, 1876.

This was the beginning of the golden period of Roentgen’s career. After his return, Roentgen exuberantly worked on perfecting his techniques in physical experimentation and gained teaching experience. He published fifteen important papers and was acknowledged as a rising star in his profession. Thus, he was recognized for the full professorship in Giessen, on the recommendation of the eminent German physicist von Helmholtz, Kirchhoff and Kundt.

On April 1, 1879, Roentgen began his journey for the prestigious Justus von Liebig University of Giessen. Though Roentgen’s initial laboratories were in cramped quarters in a private home, he was asked to design a new department which he occupied in the winter of 1880-1881. He continued his special investigations, mostly with the different properties of crystals. While he was engrossed in his experiments in these years of his life, his personal life was smashed with sorrows one after the other. First he encountered the death of his mother in 1880 and then, his father too passed away in 1884. The grief of losing his parents gave birth to a need within Roentgen to have a child. But unfortunately, destiny did not grant him to have his own children and eventually he decided to adopt Bertha’s 6 year old niece, Josephine Bertha Donges, in 1887. Roentgen produced eighteen papers when he was in Giessen, due to which he was recognized as an extraordinary scientist and was offered the position of professor of Physics and director of the new Physical Institute at the University of Wurzburg.

The golden peroid

Eventually, Wilhelm along with his family returned to Wurzburg on October 1, 1888. The new institute was located on the tree-lined Pliecher Ring which was later renamed Roentgen Ring in his honour. It was a two storey building with ample room for laboratory and lecture rooms which was just the way Wilhelm desired. During his Wurzburg experience he produced seventeen important papers- the most important of his life. This led to the appreciation for his academic excellence and he was elected as Rector (President) of the Julius Maximilians University of Wurzburg for the biennium of 1894 and 1895.Did his electors already have a premonition of what was to come?

This brings us to the significant period at the end of 1895 when many eminent scientists experimented with the properties of cathode rays and acquired conflicting results. It was supposedly the month of October when Wilhelm completely got engrossed in the investigations (of these strange rays), which prior to him were carried on by Hittorf, Crookes Hertz and Lenard. The intensity of his absorption in his experiments amplified as he progressed with the work and got so sincerely immersed in it that he toiled days and nights for it. His preliminary efforts began with accumulating the best conceivable apparatus for the cathode ray experiments. The apparatus consisted of a large Ruhmkorff induction coil for current production. The coil was attached to a Deprez interrupter that resulted in a high energy discharge. He also acquired several Hittorf-Crookes tubes and some Lenard tubes of different strengths. The Lenard type was a round glass cathode ray tube that had a small window covered by a thin aluminium foil, through which the cathode rays could penetrate. The oval Hittorf-Crookes tube had no such window but only a glass target area. Wilhelm also had a raps vacuum pump, which was essential to evacuate these tubes prior to use for more efficiency. When he assembled all his equipments in proper working order, he began his observations in solemn.

The 'Wonderous' Discovery

This brings us to the momentous day of Friday, November 8, 1895. Wilhelm was performing experiments confirming the earlier works of Lenard. He was using a low output Lenard tube wrapped in cardboards and tinfoil so that no visible light emanated, and showing the fluorescence of a small cardboard screen coated with barium platinocyanide when it was placed close to the tube and bombarded by cathode rays. His analytical mind led him to perform the experiment again with another approach, and he wondered if he could observe similar effects from all glass Hittorf-Crookes tubes of higher strength. He selected this larger tube, encased it in cardboard, connected it to his Ruhmkorff coil, darkened the room and activated the coil so as to pass current through the tube. He first confirmed that there was no visible light leakage. He observed the projected fluorescence of the screen near the tube. He was prepared to turn off the current to the tube to prepare for the next phase of his experiment, when suddenly, his eye caught the shadowy beam of a weak light from a workbench about a meter away from the tube. This light immediately attracted his attention and he continued to energize the tube. He was rewarded by a continued fluorescence of a faint green cloud of flickering light waves moving in unison with the fluctuating discharges of the coil. Highly thrilled, he ignited a match and discovered that the source of this dim light was a small barium platinocyanide screen lying on the bench. He continued to apply current to the tube, moving the fluorescent light. He was very well aware that cathode rays never travelled these distances, and he became entirely indulged in explaining these observations. He began to interrogate his findings as they did not follow the known properties of cathode rays. To find out his answer, he held different papers and books in the beam with very little dimming effect on the fluorescence. Metallic objects were seen to be outlined on the screen and while holding one object he noticed the shadow of the bones of his fingers. Impossible!!! He cried in amazement. He could scarcely believe his eyes. It was perhaps this moment when he concluded his astonishing discovery; these effects were not due to cathode rays but probably from a new type of unknown highly penetrating rays, which he named X-rays.

Over the weekend, he devoted all his time in investigating the properties of these newly discovered rays. He examined all kinds of new stuff; a set of weights, a barrel of his shotgun, a compass, a coil of wire, different types of wood and paper, glass, a door jamb and many other objects. His observations and investigations continued over next several weeks. He found out that these rays could penetrate cardboard, wood, cloth and even a thick book, but they could not go through copper, iron and other metals so well. He also found that they could penetrate flesh but not bones. The discovery of these strange rays excited Wilhelm to such an extent that he almost forgot the essence of sleep, and even if he slept, it was on

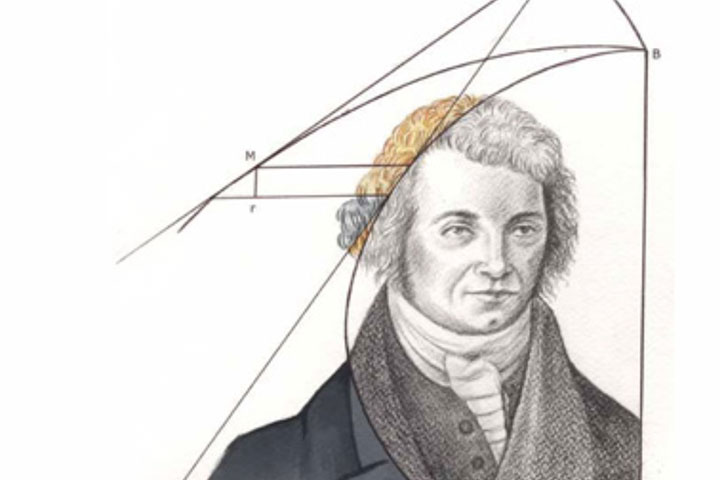

the couch of his lab. The quest to find out the hidden mystery behind these rays offered him seldom time to eat. For weeks, he had been labouring over these rays and he got so absorbed in it that one night he forgot to praise a good supper which Bertha had prepared for him. She had gradually enticed him to come and eat but he gobbled the meal in hurry. Bertha got disappointed with his behaviour and enquired the reason behind his deep indulgence in work. To mollify her impatience, he took her to the darkened room where he showed her the wonders which he had witnessed. It was the night of December 27, 1895 when he revealed his secret to the first person ever; he photographed her hand with the ‘new ray’. The x- rays showed her bones and a ring but no skin appeared. It was almost a miracle for Bertha; she was amazed with the astonishing rays through which she could see within herself. She understood why Wilhelm forgot to praise the meal she had prepared; after all, it was a discovery well worth the sacrifice of a good dinner!

The new phenomenon was so obnoxious that Wilhelm began doubting his own intellect. In spite of the astounding discovery he was still unsure of publicizing it. Even his laboratory assistants were not aware about the rays yet. He tested his discovery again and again, observing in his laboratory day and night to see any new developments, but every experiment which he performed only proved and confirmed that his apparatus and his discovery was fool- proof. Finally, he was assured and on December 28, 1895 he delivered his remarkable paper ‘On A New Kind Of Rays’ to the Wurzburg Physical Medical Society. It outlined seventeen points which were listed as the essential properties of the new rays. It was printed immediately by the society but was due to be read only until the next meeting in late January.

kudos Roentgen

Wilhelm thought to himself that rather than risking the information to the public, it was better to first take the advice of scientific colleagues and friends; eventually, he mailed reprints of that paper to them. He probably commented to his beloved Bertha, ‘Donnerwetter, now watch all hell break loose’. And his words turned out to be true. The importance of the discovery was instantly recognized by fellow scientists and the news of the discovery was released to the public.

On January 23, 1896, Wilhelm spoke publicly before the society in Wurzburg about how he discovered his ‘Wondrous rays’. The news of his discovery created a sensation across the globe; that Wilhelm had seen the bones of a hand through the skin sounded absurd. Everybody seated was desperately waiting for Wilhelm to discourse his new form of Radiation. Professors, high officials, army men, students, doctors all were present and greeted Wilhelm with enthusiastic applause. The moment he spoke of his rays it sounded like magic. Nobody could believe what Wilhelm had witnessed; it was almost a miracle for everyone. But Wilhelm proved it by taking a photograph of a famous Anatomist, Dr.Von Kolliker in front of the audience. The mass of people present could not believe their eyes and an amazed Kolliker named the rays after Wilhelm Roentgen. It was the most reminiscent moment of Wilhelm’s life. The aged Von Kolliker said that never in the last 48 years of his membership had he witnessed such an event.

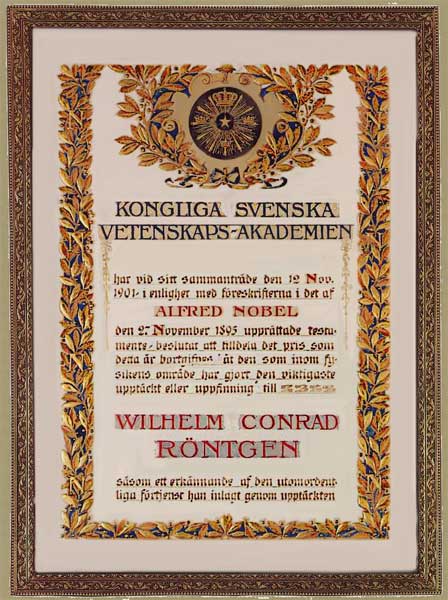

In January 1896, Roentgen was summoned to Berlin to demonstrate his discovery to Kaiser Wilhelm at the palace. Here he was awarded the crown order of the Second class and given the title of excellence. Later, on March 9, 1896 and March 10, 1897, he delivered continued communications ‘On A New Kind Of Rays’ to the Wurzburg Physical Medical Society. Mounds of medals and awards followed; these were topped by Roentgen being named the world’s first Nobel laureate in Physics. He accepted the prize in person in Stockholm on December 10, 1901.But the astonishing part was that he left the stage without delivering a speech. Perhaps the sole reason behind his behaviour was the mere fact that he never craved to be the centre of attraction.

Roentgen ostracized publicity, but every newspaper was keen to write about his ‘all penetrating rays’. Though during the 19th century, Boer war was the biggest front page news but it could not distract attention from the marvellous triumph of science which was the remarkable discovery of ‘Roentgen rays’.

An interview that he later gave to a reporter illustrates Roentgen’s own awe at his discovery.

“Is it light?” He was asked.

“No”, he replied, for “it can neither be reflected nor broken.”

“Is it electricity?”

“Not in any known form.”

“What is it then?”

“I know not”, concluded its modest discoverer.

Bombarded with Publicity

It is the truth that every revolution in the history of mankind faces immense criticisms in the beginning; same was the situation with Roentgen rays. Hundreds of articles appeared in scientific journals during 1896. Physicians saw the possibilities offered by the X-ray but the general public was not so eager to “see through themselves”. Various prolific and amusing cartoons were published with irony towards the Roentgen rays. “On the revolting indecency of seeing peoples bones we need not dwell”, said one article. “Throw the thing into the sea where the fish may contemplate each other’s bones but not for us!”

On January 25, 1896, a verse appeared in a newspaper which shows the general feeling which was dwelling in the hearts of the masses during those times.

O Roentgen, then the news is true

And not a trick or idle rumour

That bids us each beware of you

And of your grim and graveyard humour.

We do not want, like Dr. Swift

To take our flesh off and to pose in

Our bones or show each little rift

And joint for you to poke your nose in.

Whether criticism or applause, Roentgen did not pay heed to any of it. It appeared he was almost embarrassed by all the attention; all that kept him content was the gift he could offer to mankind. In the face of all the adulation, he remained humble and never tried to capitalize on his findings or patent them. He then moved on to other areas of scientific interest and never did much more with X-rays.

Withering exsistence

Meanwhile, the Bavarian government had asked Roentgen to take the chair of Physics and become the director of the Physical Science Institute at the Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich. This was a respectable promotion which he accepted and moved to Munich on March 23, 1990. He was now completely engrossed in supervising the Physics department and teaching some classes as he had turned into a popular lecturer. Apart from this, he devoted much time to the care of his beloved wife Bertha who had developed a serious kidney disease. Her health steadily deteriorated and she died on Oct 31, 1919 in her 80th year.

Following his adored wife’s death Roentgen decided to retire from the University of Munich in the spring of 1920.The post-world war I period in Munich was a difficult time, but Roentgen kept himself busy by reading and corresponding with old friends. He loved to hunt and had a hunting lodge, south of Munich in Weilheim where he spent considerable amount of time with friends, mostly recounting the good old days. Though he tried finding solace in the midst of the mountains, life had ceased to interest him since the death of his wife. Unfortunately, he developed colon trouble which slowly progressed and in early 1923 he was diagnosed with terminal colon cancer. Another matter of plight was that he was nearly bankrupt at the time of his death due to the inflation that followed World War I. The life of the legendary scientist eventually came to an end and he quietly passed away at the age of 78, on February 10, 1923. He was interred at the family plot in Giessen, where his wife and parents had also been buried. Along with his death, all his personal and scientific correspondence was also destroyed with respect to his will.

Mortal Roentgen's Immortal Rays

“The scientist must consider the possibility, which usually amounts to a certainty, that his work will be superseded by others within a relatively short time, that his methods will be improved upon and that the new results will be more accurate and the memory of his life and work will gradually disappear.”

The humility of the phenomenal scientist and observer are echoed in these words which he delivered in his speech while he attained his rectorship. Roentgen’s staggering discovery is renowned throughout the world but the persona of the man himself was known to very few. In spite of his incredible contribution to uplift mankind, he remained simple in his demeanour and modest over his achievement.

Though the inventor of X-rays was no more alive, his rays led to the progression of many theories of Radiation. Doctors began using X-rays to check broken bones and internal organs. Orthopaedists were not the only doctors who used X-rays; even dentists used Roentgen’s rays for dental imaging. Without the discovery of X-rays, millions of people could have been falsely diagnosed and died as there wouldn’t have been a way to see exactly what was wrong. Even airports began using X-rays every day for safety purposes to check luggage for hazardous weapons or drugs. X-rays were used around the world to succour people every day and it has emerged as a great influence on medical advances. Roentgen might have never known that his astonishing discovery would abet mankind in such an enormous way. Indeed, the names of prodigious scientists like Roentgen are lost in the pages of history but their work will keep benefitting mankind until the end of time.

there has to be a happening.

Newton saw an apple fall;

James Watt watched a kettle boil;

Roentgen fogged some photographic plates.

And these people knew enough to

translate or dinary happenings into something new.”

Next Biography