The might of nations and empires is measured not just by their military might; it is as much dependent on the legacy they leave behind for the future generations, so that many years later, when the bards sing about the glory days of the yore, they talk of the might, the prestige, and the loftiness of that era. When the story of the British Empire, which at its peak covered most of the discovered world, is told, one name will stand out due to the contribution of this literary canon: Rudyard Kipling.

“If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you;

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you,

But make allowance for their doubting too:”

Praised by many as the greatest writer of the British Empire, Kipling single handedly changed the perception of British literature and transformed the narrative of the Empire’s literary output. He wrote some of the greatest British poems and stories of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and appealed to a wide cross section of readers all over the world. He could appeal to the British reader just as effortlessly as to someone halfway across the world. Kipling wrote of the workers – builders, engineers, soldiers, railway workers; men who shaped the Empire with their blood and toil. He spoke the voice of children, fakirs, and animals and yet when war knocked on the doors, he could urge the nation’s youth to the battle-front with the power of his prose.

Family History

Lockwood Kipling and Alice met each other in 1863 and courted near Lake Rudyard in Staffordshire, England. They married soon after, in 1865, and moved to India the same year. However, the memory and romance of Lake Rudyard was still fresh in their mind and they decided to name their first child after the lake.

Rudyard Kipling was born in Bombay (now Mumbai), India, on 30th December, 1865. Both his parents were descendants from Methodist ministers and the two families had an equal measure of artists and high-ranking bureaucrats on each side, making them prestigious and well-connected families. They also had a daughter, Rudyard’s younger sister, who was born in 1868, and named Alice after her own mother.

Lockwood Kipling, born to Reverend Joseph Kipling, was a talented and recognized artist, well known as a painter, sculptor, pottery designer, art teacher and museum curator. He studied art at the Kensington Arts School and decided to move to India in 1865 to head the arts school of the Madras Presidency. Later, he was offered the position of Principal and Professor of Architectural Sculpture at the newly established Sir Jamsetjee Jeejebhoy School of Art in Bombay (J J School of Art). The school went on to emerge as one of the most prestigious art schools in India. Ten years later, Lockwood relocated to Lahore as Principal of Mayo School of Arts. He also held the position of Curator of Lahore Museum while in Lahore.

Alice Kipling, of Irish and Scottish descent, was one of four sisters and seven brothers born to Hannah Jones and Reverend George Brown McDonald, a Methodist minister. Alice was a beautiful and vivacious woman, and held her own among the four sisters who were all well known for their exceptional beauty. Alice’s younger sister, Georgiana, married well-known painter Edward Burne-Jones, next in line Agnes married another famous painter, Edward Poynter while the youngest, Louisa, married Industrialist Alfred Baldwin. Louisa’s son Stanley Baldwin, who was Rudyard’s first cousin, went on to become Prime Minister of Great Britain for three separate terms.

Thus three different cultures – British, Scottish and Irish contributed to Rudyard Kipling’s bloodline, while the family origins could be traced 400 years back to Holland. Rudyard’s parents were true ‘Indophiles’, and loved Indian culture in its entirety. They embraced the lifestyle of British-Indians, which was largely an insular society of British subjects living in India with the comfort of attendants, servants, estates and all the benefits of a ruling class. Rudyard too considered himself to be so, even though he was to spend a large part of his later life outside India. This life-long love for India gave rise to a dichotomy that contributed in no small part to his recurring themes of national identity and allegiance. The wooden cottage where Rudyard Kipling was born still stands in the campus of J J School of art.

Childhood Years

From his birth, till the age of five, Rudyard lived with his family on the campus of J J College of Arts. He later described his childhood memories of Bombay as “days of strong light and shadows”. It was an idyllic life, and this was where his love for India would grow from.The bustling city of Bombay, with its myriad variety of religions, colours and languages was forever imprinted on the young child’s mind. The family had a large army of attendants and caretakers to look after the children and household chores. The servants would speak in the local language while attending to the children and narrate to them local stories and poems.

A Return to the Motherland

British Indians gave to India, among other things, a culture of boarding schools. Since most British subjects based in India were from a military or administrative background, their jobs required them to travel extensively around the country. Thus, the prevailing practice of the time was to enroll children into boarding schools, where they grew up amongst their own kind and had access to British customs and manners. Alternately, they were sent back to Britain to live with couples that boarded children of British subjects living across the vast Empire. John and Alice too, decided to send five year old Rudyard to a boarding school in England, along with his three and a half year old sister. The children were sent off to Southsea, Portsmouth to board with Captain Pryse Agar Holloway and his wife, Mrs. Sarah Holloway.

Following Captain Holloway’s death, the caretaker lady, Mrs. Holloway turned very abusive towards the children, neglecting them and punishing them with equal measure. The only escape from the cruelty was the magazines and books that his mother sent to him, including Treasure Island. Rudyard and Alice lived there for six years, from 1871 till 1877, and would later associate these years with painful memories of mistreatment by Mrs. Holloway.

The children had never experienced beatings before, and the only respite the children got was the month long Christmas vacation with their dearly beloved maternal aunt Georgiana and her husband at their house in London. Rudyard described it as "a paradise which I verily believe saved me". His uncle – Pre Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones, who was a well-known figure, went on to become a major influence in Rudyard’s future artistic direction. Their children made excellent playmates for the Kipling children, and for a month, the cruelty was forgotten in a stream of songs, made up plays and laughter. His mother arrived in Britain in 1877, and after finding out the truth, immediately removed the children from the Holloways care. Rudyard recalled later: "Often and often afterwards, the beloved Aunt would ask me why I had never told any one how I was being treated. Children tell little more than animals, for what comes to them they accept as eternally established. Also, badly-treated children have a clear notion of what they are likely to get if they betray the secrets of a prison-house before they are clear of it".

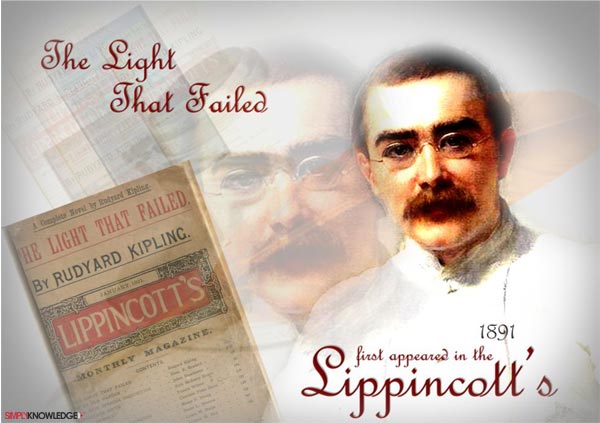

The next year, in 1878, Rudyard was admitted to the United Services College at Westward Ho!, North Devon. This was an expensive preparatory school for boys aspiring to join the British Army but poor eyesight and mediocre results soon ended Rudyard’s military career. Initially, the traumatized boy found the new school, with its strict military-like regimen to be rough, but later he went on to fit in and find many friends, falling in love with literature on the way. He was teased and bullied to some extent here as well, and given the nickname “Gigger”, because of his glasses, but what he admired the most about the institution was the non-conformist Headmaster, Cornell Price. He became the editor of the school newspaper and started writing his first book – Schoolboy Lyrics. He would often visit his sister Alice (fondly nicknamed Trix), who was in a different boarding school now, but still in Southsea. On one of his visits there, Rudyard fell in love with his sister’s roommate – a young girl named Florence Garrard. He modeled the heroine of his first novel, “The light that failed” (1891) after Florence. Even at this early age, Rudyard’s writings were influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites – a brotherhood of mid-eighteenth century artists who rejected rote-based learning of arts and “art for the sake of it”, reveling in highly detailed representations of heartfelt topics.

Rudyard’s parents were counting on his academic abilities to get him a scholarship at Oxford College since they lacked the financial wherewithal to buy him a seat there. However, once it became clear that the scholarship was out of the young student’s reach, Lockwood Kipling obtained a job for him in Lahore (now Pakistan) as Assistant Editor of the Civil & Military Gazette, a small local paper. The senior Kipling enjoyed considerable clout in the city, owing to his important position as head of the Mayo College of Arts and Curator of the Lahore Museum.

Rudyard Kipling set sail for India on 20th September, 1882, arriving into Mumbai. He was extremely overjoyed to be returning to the land of his childhood and a place that still held very strong and poignant memories. He described the return in his own words as: "So, at sixteen years and nine months, but looking four or five years older, and adorned with real whiskers which the scandalized mother abolished within one hour of beholding, I found myself at Mumbai where I was born, moving among sights and smells that made me deliver in the vernacular sentences whose meaning I knew not. Other Indian-born boys have told me how the same thing happened to them". So strong was his childhood bond with India that it soon overshadowed the years spent in his motherland, as evident from these words: "There were yet three or four days’ rail to Lahore, where my people lived. After these, my English years fell away, nor ever, I think, came back in full strength".

The Indian Years

After an over-land journey from Mumbai, Rudyard reached the bustling metropolis of Lahore, which was one of the most vibrant cities in the British Empire. Upon joining his first job with the Civil & Military Gazette, Rudyard instantly immersed himself into writing at an accelerated pace. Due to his ease with the Indian language as well as English, Rudyard found many doors opened to him and he managed to live in a world between the disparate communities of the multi-ethnic city that Lahore was. He soon started taking nightly walks in the city of Lahore to escape from his insomnia, gaining access to places like opium dens and brothels. Fortunately, he always remained an observer and not a participant.

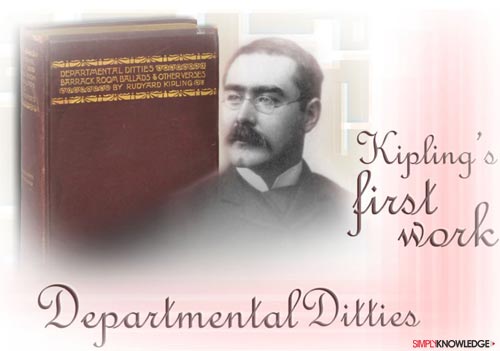

The Civil & Military Gazette was published six days of the week and as the assistant editor, Rudyard was constantly pushed hard. Yet, he wrote unceasingly, describing the newspaper as his "mistress and most true love". Inspired by this experience, he managed to find time to pen his first collection of verses in 1886, aptly titled “Departmental Ditties”. The book was originally published by A. H. Wheeler and Co., which was a chain of bookstalls on Indian Railway stations. Sir William Hunter, Chancellor of Bombay University read the book and reviewed it in the London Academy, commenting, “The book gives promise of a new literary star rising in the east. What the young writer experienced in handling the heavy machinery in hot tropical conditions would instill in him a lifelong respect for the working class, the builders, the engineers, the men who toiled in their sweat daily to create the Empire”.

It was a common practice among the Anglo Indians to move to hill towns in Northern India to avoid the searing heat of the plains during the Indian summers. Hill stations like Simla, Mussoorie, Dalhousie etc., which later came to be known as summer capitals adopted much of the British culture, to reflect their need to feel at home. Rudyard’s family first visited Simla in 1883, returning there each year for five years for their summer vacations. His father served as the Minister in the Church at Simla and the town fascinated Rudyard so much that it appeared constantly in his short stories that featured in the Gazette. The carefree days spent in these magical hills were to have a lifelong effect on Rudyard Kipling, and they indeed left an indelible mark on his future writing as we can see from his description: "My month’s leave at Simla, or whatever Hill Station my people went to, was pure joy—every golden hour counted. It began in heat and discomfort, by rail and road. It ended in the cool evening, with a wood fire in one’s bedroom, and next morn—thirty more of them ahead!—the early cup of tea, the Mother who brought it in, and the long talks of us all together again. One had leisure to work, too, at whatever play-work was in one’s head, and that was usually full."

Rudyard Kipling was made a member of the secret society of Freemasons in 1885, even though he had not yet turned 21, which was the minimum eligible age. The Freemasons was a worldwide organization, chiefly devoted to the craft of masonry, architecture and stonework, and Rudyard was very enthusiastic in his love for the brotherhood.

In 1887, he was transferred to Allahabad in northern India to join the Gazette’s sister publication - The Pioneer. The pace of his writing grew even more frenetic, and in the next year, he published six separate collections of short stories, totaling 41 stories. These collections were: Soldiers Three, The Story of the Gadsbys, In Black and White, Under the Deodars, The Phantom Rickshaw, and Wee Willie Winkie – all of which were published by A. H. Wheeler’s Railway library. Rudyard wrote many short sketches as well for publication in The Pioneer, which were later released as part of “From Sea to Sea and Other Sketches, Letters of Travel”.

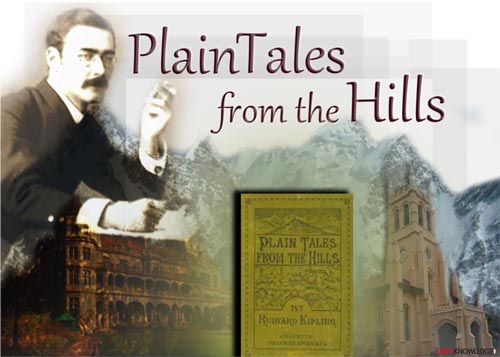

The Pioneer newspaper however, discharged Rudyard Kipling from their staff in 1888 following a dispute. The newspaper objected to Rudyard publishing stories that he wrote for them as separate books. He sold the rights to his six collections of stories and Plain Tales from the Hills for a total of 250 pounds plus a small royalty, and decided to use this money, along with the severance pay from The Pioneer to travel back to London to establish his literary career. Rudyard’s stories had made their way to Britain and word of his talent was already beginning to spread, so much so that many hailed him as the literary heir to Charles Dickens. London was the literary center of the world during that era, and a young Rudyard Kipling was aware that though he held much potential, he would have to move back to England to fully realize it, despite his overwhelming love for India.

Rudyard left India on 9th March, 1889. But before reaching London to fulfill his destiny, he wanted to do what every youngster wants. Travel the world. See new continents. Meet people. He decided he would travel through America and explore the New-World for himself. Perhaps he wanted to meet “Indians” (as the Native Americans were called) from a different part of the world. His ship travelled eastwards from the port of Calcutta (now Kolkata) to Rangoon, followed by Singapore, Hong Kong and arrived at Japan, where he publicly criticized the Japanese middle-class for their eagerness to adopt western values and fashions, at the expense of their indigenous culture. Leaving Japan behind, the ship set sail again, crossed the Pacific Ocean and finally docked at San Francisco on the West Coast of America. From there, he moved northwards over land, into Canada, turning back to America and continuing eastwards through the heart of the country. The journey took a little over six months, with halts at most of the major cities along the way, one of which resulted in a meeting with the great American writer Mark Twain. Most of the North American continent was still The New World - pristine and undeveloped and Rudyard Kipling’s journey, coming soon after the American Civil War documented an important juncture in the fledgling new nation’s history. Continuing his eastward direction to England, he set sail again from Boston, sailing across the North Pacific Ocean, finally docking at Liverpool in October 1889.

London – Appointment with Destiny

Upon arriving in London, Kipling did not encounter much difficulty in finding publishers for some of his short stories, and he soon settled down into a modest house. He described his new accommodation as: “Meantime, I had found me quarters in Villiers Street, Strand, which forty-six years ago was primitive and passionate in its habits and population. My rooms were small, not over-clean or well-kept, but from my desk I could look out of my window through the fanlight of Gatti’s Music-Hall entrance, across the street, almost on to its stage. The Charing Cross trains rumbled through my dreams on one side, the boom of the Strand on the other, while, before my windows, Father Thames under the Shot Tower walked up and down with his traffic.”

His next novel, published in 1890 was called The Light That Failed. It first appeared in the Lippincott’s monthly magazine in 1891. The novel was mostly set in London, but many of the key events in the book transpire in India and Sudan, pointing to the exotic inspirations in the young writer’s head. The novel was adapted for many movies and plays and became well known in the London literary circles, further boosting the aura of talent that was being attributed to him.

He met an American agent and publisher - Wolcott Balestier, who went on to become one of his closest friends, resulting in their collaboration on his next book. During his early years in Lahore, Kipling had been completely taken in by the Mughal Architecture of the city, and the Naulakha Pavilion of the Lahore Fort, in particular, truly fascinated him. His next novel was inspired by this beautiful enclosure of one of the most beautiful forts in the world and Kipling named the novel The Naulahka, misspelling it deliberately.

Coming of Age

Kipling had always been a weak child, and in 1891, his health had started giving him concern. His doctor cautioned him against living in the damp conditions of London, advising him to travel to more sunny climates. Once again, Kipling packed his bags and embarked on a voyage across the pearls in the crown of the British Empire – South Africa, Australia and New Zealand, followed by what would be his final trip to India, to celebrate Christmas with his parents. Whilst in India, Kipling proposed through telegraph to Caroline Starr Balestier – his publisher and dear friend Wolcott’s sister and she agreed to marry him. They had met in London a year earlier, and courted briefly. Enjoying the return to his favourite place in the world,looking forward to spending Christmas in the company of his family and a sealed marriage proposal in hand – life seemed full of joy to the young man.

However, darker events soon clouded this happy period of Kipling’s life, forcing him to rush back to London due to Wolcott’s sudden death from Typhoid fever. London was in the midst of an influenza epidemic and death literally hung in the air. Kipling’s next collection of short stories, Life’s Handicap, with a contrastingly ironic theme of his happy days in India was released during this period.

On 18th January, 1892, Rudyard Kipling married Caroline Starr Balestier or Carrie as she was known affectionately, soon after his arrival back into London. Among the attendees was the great American writer Henry James, who “gave away the bride to the groom”. The Kipling couple embarked on a world tour for their honeymoon, arriving in Canada and from there, travelling on to Japan. By the time they reached Japan, bad news followed them, in the form of their bank’s failure due to an earthquake, which resulted in the loss of almost their entire savings. With just the clothes on their back and a trunk, they made their way back to Carrie’s home in Vermont, USA. The couple was expecting their first child by now, and took up a modest cottage on rent, stocking it with the most basic necessities and cutting out on luxuries in order to set up their first home. They named the house, Bliss Cottage, and happiness soon returned to their lives in the form of their first daughter, Josephine. In Kipling’s own words, Josephine was born "in three foot of snow on the night of 29 December 1892. Her Mother’s birthday being the 31st and mine the 30th of the same month, we congratulated her on her sense of the fitness of things..."

Home is Where the Hearth is

Bliss Cottage would also go on to inspire one of Kipling’s greatest works, The Jungle Book: “…workroom in the Bliss Cottage was seven feet by eight, and from December to April the snow lay level with its window-sill. It chanced that I had written a tale about Indian Forestry work, which included a boy who had been brought up by wolves. In the stillness, and suspense, of the winter of ’92 some memory of the Masonic lions of my childhood’s magazine, and a phrase in Haggard’s Nada the Lily, combined with the echo of this tale. After blocking out the main idea in my head, the pen took charge, and I watched it begin to write stories about Mowgli and animals, which later grew into the two Jungle Books.”

The growing family needed more space, and so the couple bought some land of their own, near the Connecticut River, and built a new house, naming it “Naulakha”. The primary reason for the eastern name they gave to their house was Kipling’s love for the Naulakha Pavilion of the Lahore Fort, but it was also meant to be a mark of respect to his dear departed friend, publisher and brother in law – Walcott Balestier. Kipling called this new home his “Ship”, and the tranquil, sunlit estate inspired him to continue writing at an ever-growing pace.

Over the course of the next four years, 1893 - 1897, Kipling wrote unceasingly, publishing one book after another. The two Jungle Books were followed by a collection of short stories called The Days Work and a book of poems titled The Seven Seas.

Kipling’ second daughter - Elsie Kipling, was born in February 1896. The birth of his second daughter and his rising fame, coupled with this period of homestead stability led to an upsurge in Kipling’s writing output. However, the atmosphere in Vermont was rapidly turning unwelcoming towards him. Anglo-American ties took a steep downturn in 1895 due to political developments regarding America’s insistence on arbitration in a border dispute involving Venezuela and Britain. Though Kipling remained a much-adored writer in America and had many loyal friends and followers, the vitiated atmosphere must have led him to feel insecure regarding his family’s safety, as the tensions rapidly ratcheted into talks of war between Britain and America. A second and unrelated reason led to a hastening of his decision to exit America. His brother in law Beatty Balestier, had taken over as Kipling’s publisher following Walcott Balestier’s death. Relations between Beatty and Kipling had been souring over some years and finally culminated into a major public incident, with a drunken Beatty publicly threatening Kipling with physical violence. Though Beatty was known to have problems with alcohol and was taken into custody subsequent to this incident, the incidence left Kipling fearing for his family’s safety.

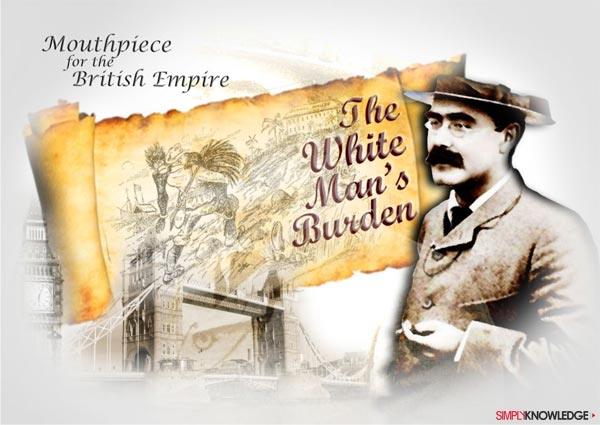

The White Man’s Burden

In July 1896, the Kipling family left America and sailed once again to Britain. Kipling moved to a seaside home in Devon and resumed writing immediately. The new house was, according to Kipling’s own admission, a lot less cheerful than the one they had left behind in the green woods of Vermont, but nothing could slow down his writing. Further good news came in the form of their first son - John, in August 1897. As Kipling’s fame and standing as a writer grew across Britain and her colonies, his writings took a decidedly political angle, with poems like The White Man’s Burden creating controversy when released, due to the unabashedly imperial nature of the writing. He was labeled as a mouthpiece for the British Empire, and attracted some criticism for the thinly veiled references to racial attitudes prevalent at the times towards third world societies. The Victorian-era attitudes of empire building, which alluded to the “White Man’s Duty” to save the natives of the colonies from their savage, self destructive ways were often more of an echo of the British Society that Kipling saw rather than his own attitude, as he had never been a racist individual.

South Africa – A First Taste of War

Kipling, who had already travelled to South Africa alone once, took his family along for another visit to the British colony in 1898, for what would turn into an annual vacation for the next ten years. The family greatly enjoyed their time there. Leading luminaries of South Africa, such as politicians, writers and artists welcomed him with open arms, as befitting his newfound status of “Poet of the Empire”, and Kipling made many friends among them. This was also an important period in the history of the country as the Second Boer War, fought between the British Empire and the Afrikaans speaking Dutch settlers was undertaken during much of these ten years, giving Kipling an important insight into the underlying and resultant politics of the country.

During the war, Kipling campaigned to raise money for the British Army and contributed to army publications. Even though Kipling’s stance regarding the war was decidedly pro-British, it was an opportunity for him to understand the ground situation in the conflict, fraught as it was with imperialistic ambitions and nationalistic undertones. The resultant peace treaty borne out of the conflict, which gave birth to the Union of South Africa, came about at a period when Kipling once again took up journalistic reporting, writing for the British “commandeered” newspaper, “The Friend”.

Following the success of Stalky & Co., a collection of short stories recalling his school days at the United Services College, which came out in 1897, Kipling moved to Sussex and settled into a 16th century house called Batemans. The old house had limited amenities, but Kipling perceived it to be a lot more cheerful than the house they left behind in Devon.

A Very Personal Loss

Amidst all this happy and cheerful time tragedy suddenly struck the Kipling family when Josephine, the eldest daughter passed away in 1899, from pneumonia that she contracted during a visit to the United States. Kipling, as well as his younger daughter, Elsie, fell sick to the same illness but they managed to recover. However, Josephine’s death had to be kept a secret from Kipling until he recovered fully, in order to prevent him from relapsing. Accordingly, the physician who had served as the family doctor during their days in Vermont was summoned and he advised moving Josephine to a hospital near the hotel where Kipling was recovering. When news of his dearly beloved daughter’s death finally reached Kipling, it shattered him completely and altered his personality irrevocably. In her memoir, written many years later, Elsie wrote: "There is no doubt that little Josephine had been his greatest joy during her short life. His life was never the same after her death; a light had gone out that could never be rekindled."

Just So Stories for Little Children was published soon after, in 1902, as Kipling’s way of saying goodbye to Josephine. Every night before going to bed, Josephine used to insist on hearing stories from her father who would make them up as he went along. Sometimes, when he would tell a story differently from an earlier version, Josephine would say, "Not like that, Daddy. Tell it just so”. Kipling drew all the illustrations in the book himself, and interspersed the stories with private jokes that the father and daughter shared, as if narrating the stories to her one last time as she slipped into a final sleep.

The preceding year, 1901 saw the publication of Kim. It underlined once again Kipling’s reputation as the greatest chronicler of the “Raj”, narrating the story of an Irish boy orphaned in India, set against the backdrop of “The Great Game”, a political drama played out between the Russian and British Empires for the control of central Asia. The book, which vividly presented an accurate picture of India at the turn of the 19th century, with all its superstitions, religions, bazaars and political espionage - was instantly recognized by many critics as one of Kipling’s greatest works, for it straddled the world of children’s literature as ably as it could the world of serious fiction.

Following the success of Kim, Kipling’s writing took a significant detour in the form of science fiction. He published two science fiction stories, With The Night Mail (in 1905) and As Easy As A B C (in 1912), which were set in a 21st century fictional world he referred to as Aerial Board of Control. Kipling recognized that in the future power would rest with those that would hold control of the skies.

Puck of Pook’s Hill, a collection of short fantasy stories, set in different periods of English history was published in 1906. It was unique in the way that it borrowed incidents and characters from real life and previously published British literature.

Success – The Ultimate Satisfaction

The Nobel Prize for Literature was awarded to Kipling in 1907, with the following foreword to the citation: "in consideration of the power of observation, originality of imagination, virility of ideas and remarkable talent for narration which characterize the creations of this world-famous author". Kipling was the first English writer to receive this exalted prize. The Nobel Prize underlined the global appeal that Kipling wielded now and his fame was at its peak during these years, with contemporaries across the world acknowledging the power of his writing. Previously, many critics had hailed him as a mouthpiece of the British Empire and its imperialistic tendencies, linguistically beating the war drum to march off Britain’s youth into battle for the purpose of empire building.

Rewards and Fairies, another collection of short stories and poems was published in 1910, and employed a style similar to Puck of Pook’s Hill. It conjured similar characters and narratives, borrowing the lead character of Puck from the earlier book, and expanded more on the theme of using children’s stories to educate them about English history, both real and literary.

One of the poems in the book, “If”, was voted by viewers of BBC in 1995 as UK’s favourite poem. Kipling later recalled that the inspiration behind the poem was a battle between the British and the Boers during the “Battle of the Boers” for the control of South Africa. The poem, which spoke of stoicism and self-control in the face of adversity, was hailed as an evocation to the British qualities that had served the Empire so well.

Always a Right-Wing Conservative, Kipling was very critical of the liberal government at the helm of British affairs from 1906 till the start of WW-1. He was openly hostile to their policies and pacifist attitudes. He supported increased military spending and compulsory military service and many of his critics accused him of mirroring German military expansionist policies. He was also accused of being supportive of German Junkerism, which advocated a rigidly hierarchical social structure governed by an elite military class. Despite being an avowed nationalist and a champion of the British cause, Kipling was still sympathetic to the cause of the Irish Unionists. Ireland - a British colony, much like India, had been fighting for home rule, which would have meant a weakening of the British powers there. Kipling was supportive to their cause to the extent of being friendly with leaders of the movement - dedicating a poem, Ulster, in 1912.

The onset of the First World War in 1914 saw the British government employing the talents of many of its leading writers into wartime service. Many famous writers, including Kipling were used to generate propaganda, which included writing pamphlets, newspaper articles, jingoist literature and other materials promoting Britain’s national interests.

The Great Toll of War

Kipling was decidedly supportive of WW-1. He was in awe of the German Army, and at the same time, wary of the role it could play in Africa and Europe. He perceived Germany as the one European nation that could challenge British hegemony across the world. But it should be kept in mind that the two nations had extremely hostile relations at this point in history, and Kipling was always a nationalist, a patriot to the core.While he could arguably be called jingoistic, Kipling was very aware of his role as the nation’s prevailing bard, a bard who spoke not only of exotic lands and peoples in faraway places, but also called upon the nation to rise to arms when needed.

However, his involvement with the war was to be a lot more personal. His only son - John, whom Kipling affectionately referred to as “Jack”, had been drafted into the British Army in August 1914. The 18 year old boy suffered from extremely poor vision, much like his father and had been rejected thrice in his attempts to join the army. It was as much John’s wish as his father’s that he serves the King and Country, and Kipling ultimately had to resort to pulling strings to get John admitted into the Army. Perhaps Kipling was trying to fulfill his own ambition of a military career through his son.

Kipling was by now an extremely powerful and well-known figure in Britain, and counted the King of Britain, and high-ranking military officials among others, as his friends. The question of anything other than active service - which meant fighting on the warfront, did not arise, and John was shipped off to the battle lines on 15th August, 1915. His final words to his mother were "Send my love to Dad-o”. Kipling met his son for the final time some three days earlier, and never saw him again. John Kipling died on only his second day on the battlefront. His body was never recovered and he was officially listed as “missing”. Kipling was devastated by this news and embarked on a three-year search for his son; finally accepting John’s death only after the Great War had ended in 1918. Kipling wrote a public eulogy in 1915, called My Son Jack. For many years afterwards, Kipling was wrought with guilt over his role in getting John drafted even though he was physically disqualified, and by some accounts he gave vent to this feeling in this line: "If any question why we died/ Tell them, because our fathers lied".

Following his son’s death, Kipling became a broken man and the pace of his writing slowed down. A Diversity of Creatures – a collection of his short stories appeared in 1917. He devoted a lot of his time to post war memorials for the British soldiers, who died in service. He wrote a historical account of his son’s regiment - The Irish Guards, as well as a short story called The Gardener, which talked of the men tending to the gardens of the British War Memorials, followed by The Kings Pilgrimage, which depicted King George’s tour of the cemeteries and memorial gardens.

Even though Kipling was always touted as the voice of the “White Empire” and a proponent of the British Raj, he was never a racial man and always promoted the rights of other races. However, with advancing age, as his imperialist sentiments grew stronger, he grew increasingly out of touch with political, moral and social realities. He always remained cautious towards the communists, or the “Bolsheviks”, as they were known then. In 1920, soon after the Russian Revolution, Kipling, along with writer Rider Haggard formed the short-lived “Liberty League” to combat “Jewish-Funded Bolsheviks”. The main aim of the organization, for which the men invited donations from the public, was to counter the “Jewish-Funded” Bolshevik activities, such as trade unionism within the UK. Despite this, Kipling could never be pointedly addressed as an anti-Semite, as he stood against what he perceived to be a Jewish conspiracy to take over the world, and not against Jewish people per se.

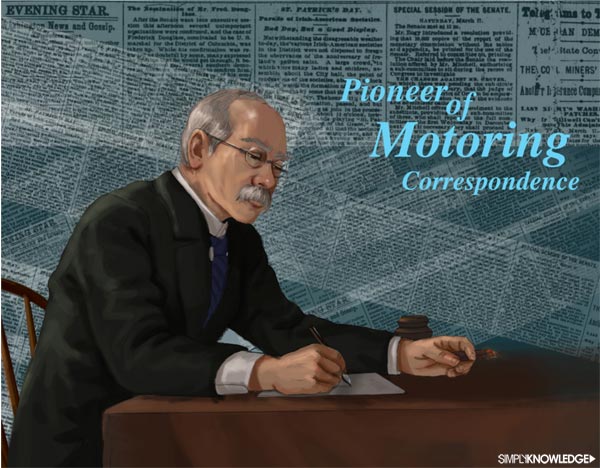

During the 1920’s Kipling continued to travel, and kept writing as a travel correspondent. He became one of the pioneering “motoring correspondents”, travelling around England and abroad in his chauffeured car and reporting enthusiastically.

Death - The Final Chapter

Rudyard Kipling breathed his last on 18th January, 1936, at the age of 70. His death was attributed to a perforated ulcer. In a strange twist of fate, a magazine incorrectly announced his death even as he was still in hospital. Kipling’s response was typically tongue in cheek, "I've just read that I am dead. Don't forget to delete me from your list of subscribers". Kipling was given a State burial, and his body was interred in Westminster Abbey, next to Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy. British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin was one of the pallbearers, along with a serving General, an Admiral and the Dean of the Cambridge College. Notably, leading British writers of the era were conspicuously absent from the ceremony, which served as a reminder of the shift in Kipling’s image – from the great writer, to a mouthpiece of the Empire. Something of Myself, an autobiographical account was published posthumously, a year after his death.

Legacy

During his lifetime Rudyard Kipling was often hailed as the greatest living British writers of his time. His books became essential reading not just in the UK, but across the world, particularly in India, South Africa and America. Unlike many other great writers of his era, he did not just write serious literature for the grown up reader – his stories traversed the world, from one continent to another, from collections of poems and stories to children, to naval doctrines and military and political matters. He could be the voice of animals, or of a young native orphan child; he could be the voice of characters borrowed from previously published British literature, or of an old fakir. It was this ability to speak many voices that gave Rudyard Kipling his success around the world, across all age groups.

Next Biography